Patient and Contextual Factors Related to the Decision to Hospitalize Patients From Emergency Psychiatric Services

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Mental health care reform has brought an increasing emphasis on community care, with concomitant reductions in inpatient psychiatric resources. Hospitalization remains a necessary and integral component of the mental health care system, but it is taking on a more specialized role. Examining the circumstances in which hospitalization is indicated can help clarify emergency psychiatric practices and determine whether patients' needs are being met within this changing environment. This pilot study examined the impact of selected patient and contextual characteristics on the decision to admit patients to inpatient psychiatric units and assessed the utility of the Severity of Psychiatric Illness (SPI) scale for monitoring clinical practice in emergency psychiatric services. METHODS: Crisis workers in two emergency psychiatric services crisis teams in Toronto, Canada, used the SPI in the assessment of 205 visitors to the services during the winter of 1998-1999. Contextual characteristics, including bed availability, service site, and the admitting physician's level of training, were recorded. Multivariate logistic regression was used to assess the relative contribution of patient and contextual variables in the admission decision. RESULTS: The severity of axis I symptoms and difficulties with self-care were significantly associated with the decision to admit. Site, bed availability, and the admitting physician's level of training did not appear to be associated with clinical decisions. CONCLUSIONS: Patients with the most need are being admitted to inpatient units despite significant systemic pressures on inpatient services. The SPI is a useful and discriminating tool for evaluating clinical practice in emergency services.

Mental health care reforms have emphasized a shift from hospital to community-based care with the goal of developing care models that provide treatment in the least restrictive environment. Hospitalization remains a necessary and integral component of the mental health system, but it is taking on a more specialized role as the noninstitutional care system develops. Specialized emergency psychiatric services are an important component in a comprehensive mental health care system, serving as a gatekeeper to inpatient care for people who need mental health stabilization and treatment (1,2). Given this critical role, a considerable body of research has accrued in the past few decades elucidating emergency service practices related to psychiatric admissions. Much of the evidence points to the significant role of clinical need in the decision to admit a patient. However, given the changing health care context, including more restricted access to inpatient beds, the need to continue monitoring the practices of emergency services is critical. Information about such practices can also contribute to the growing emphasis in the health field on identifying and delivering best-practice care (3).

Potential influences on the decision to admit include the patient's condition—for example, symptom severity and social and community functioning—and institutional constraints. A substantial body of research demonstrates a relationship between clinical status and likelihood of admission. Bengelsdorf and associates (4) developed a three-item crisis rating scale to predict hospitalization that included dangerousness and ability to cooperate. Lyons and colleagues (5) found that suicide potential, danger to others, and symptom severity were the best predictors of hospital admission. Others (2,6,7,8) have reported similar findings, demonstrating that admission is more likely among visitors to emergency psychiatric services who are rated higher on indicators of risk, such as danger to self, danger to others, and impaired capacity for self-care, and on degree of psychopathology, such as seriousness of diagnosis, having a major mental disorder, and presence of psychosis, impulse control, or depression. The impact of substance abuse is less clear; studies show both higher and lower likelihoods of admission for visitors to emergency psychiatric services who are substance abusers (2,9,10). Fewer studies have assessed the role of social factors. However, there is evidence that the likelihood of admission is higher when the individual is accompanied by a family member (10,11), has more social support (2,4), and demonstrates poor community functioning (7).

Although patient-specific determinants should predominate in admission decisions, contextual factors have also been found to play a role. Way and colleagues (12) found variances across hospital sites in admission practices. The likelihood of admission has been found to vary with the time of day the patient arrives at the emergency service (10,11,13). Several studies have suggested that psychiatrists who are still in training are more likely than more experienced psychiatrists to admit patients (14,15,16). More recently, concern has focused on the impact of systemic changes—especially reductions in inpatient beds—on determinants of admission decisions. Segal and colleagues (8) found that institutional constraints such as clinician workload, the clinician's experience, and bed availability did not influence the decision to admit, whereas others have found an association between admission and the availability of beds (11,13).

In Ontario, as elsewhere, the environment of emergency psychiatric services has changed, with cuts to inpatient psychiatric services and consolidation of emergency services across hospital sites. These changes are often cited by the broader community as the reason ill patients are turned away from emergency services. The pilot study we report here attempted to address this question by examining the relative influence of individual and contextual factors that lead to inpatient admission. A second goal of the study was to test the feasibility of monitoring clinical practice in emergency psychiatry services by using the Severity of Psychiatric Illness (SPI) scale (17). This brief decision support tool was developed by Lyons and colleagues (5) to assess the need for inpatient admission, and it has been used successfully in emergency psychiatric settings. It has the potential to promote more homogeneity in psychiatric emergency assessment practice (2) within the constraints of the enormous time pressures under which emergency psychiatric staff operate (18).

Our study addressed three specific research questions. First, what patient characteristics predict inpatient admission? Second, do contextual variables—specifically, bed availability, the physician's level of training, and site—influence the decision to admit independently of clinical considerations? And third, is the SPI a useful and practical tool for monitoring emergency psychiatric practice?

Methods

Setting

Two emergency psychiatric services in Toronto, Ontario, participated in the study. The Clarke site of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health is the emergency service of a psychiatric tertiary care hospital. The Wellesley site of St. Michael's Hospital is a psychiatric emergency service housed in the emergency department of a general hospital. Both are university affiliated, and both use a team approach. Crisis or intake workers are on shift at both sites on weekdays from 8 a.m. to 11 p.m. The annual number of walk-in visitors from April 1998 through March 1999 was about 3,000 at the Clarke site and 1,900 at the Wellesley site.

The study protocol was approved by the research ethics board of the University of Toronto's department of psychiatry.

Data collection and measures

Crisis workers were asked to complete a one-page questionnaire for each visitor to the emergency psychiatric services at the time of the initial interview. The questionnaire collected demographic data; number of previous hospitalizations; information on contextual variables, including number of beds currently available and training status of the admitting physician (staff physician or resident); ratings on the SPI; and disposition information.

The SPI scale was developed as a client-level decision support tool to assess need for services, especially inpatient care. Impairment is rated across 14 domains on a 4-point scale from 0, none, to 3, severe, with unique behavioral descriptors anchoring each rating. Specific domains include suicide risk, danger to others, severity of symptoms on axis I, difficulty with self-care, personality disorder (axis II), vocational impairment, substance abuse or dependence, medical complications, family disruption, residential instability, motivation, medical compliance, family involvement, and temporal consistency (12-month impairment). Completing the instrument takes five to ten minutes, and the result is a profile of ratings rather than a total score. The SPI's validity has been established in a number of studies. An SPI administration manual is available, and training can establish interrater reliability within several hours (5,17,19,20).

Disposition options included admitted; admitted to "no bed" and held in the emergency department until a bed became available; and a number of noninpatient options. The crisis worker recorded his or her recommended disposition after the initial interview. The final disposition, as decided by the staff psychiatrist or resident, was added to the form when the case was completed.

The research team met with the crisis workers before the start of the study to introduce the project and discuss their role. The first author provided a half day's training at each site to establish interrater reliability. The workers were not informed of the research hypotheses.

For the purpose of the pilot study, data were gathered only during shifts when crisis workers were available to complete the questionnaires—namely, Monday through Friday during the day and evening shifts. Staff psychiatrists are available on-site during the day and residents during the evening, allowing a comparison of decision making by physicians at various stages of training. Crisis workers were asked to complete the SPI for all visitors to the emergency psychiatric services until a minimum sample of 100 patients per site was reached.

Analysis

Univariate analyses using chi square tests examined the association between each patient and contextual variable (the independent variables) and whether or not the patient was admitted (the dependent variable) at each site. Multivariate logistic regression modeling techniques, using two steps, were applied to the combined data set to assess the relative contribution of selected patient and contextual variables to the admission decision. The selected patient items replicate Lyons' predictive model and include suicide risk, danger to others, and severity of symptoms (5), with self-care added because it is a criterion for involuntary admission or detainment in a psychiatric facility. The first step included these four clinical variables. The second step added the site and two other contextual variables of interest—the level of training of the physician making the final disposition decision (staff physician or resident) and the availability of inpatient beds. To assess the possibility of site differences in the influence of the other contextual factors, interaction terms were added. Following the guidelines of Norman and Streiner (21), we sought a minimum sample of 90 assessments per site to adequately test a nine-variable model. SPSS 7.0 was used for the analyses.

Results

Data were gathered from November 1998 through March 1999. Rates of SPI completion varied, and it was necessary for the first author to visit sites regularly to sustain motivation. Assessments were completed for 103 visitors at the Clarke site and 102 at the Wellesley site, accounting for 10 to 15 percent of all visitors to the two emergency psychiatric services sites during the weekday daytime and evening shifts during this period. Thus our study used a convenience sample rather than a representative sample. Although the sample cannot be assumed to represent all users of emergency psychiatric services, the data we obtained can be used to address the study goal of identifying determinants of psychiatric admission. The quality of the assessment data was high, with the exception of three SPI domains in which ratings were frequently missing—family disruption, medical compliance, and family involvement. Because of high rates of missing data (17 percent to 19 percent), these domains were excluded from the analyses.

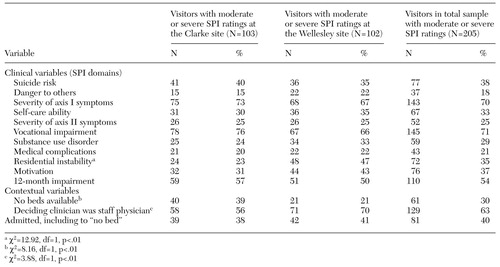

Of the 205 visitors assessed, 63 percent were men, and the mean±SD age was 37.5±12.2 years. As Table 1 indicates, a large proportion of the study participants had moderate or high severity of symptoms in axis I and previous-year impairment, suggesting a chronic and highly impaired group. About a third evidenced considerable risk of self-harm or self-care. More than a third were experiencing residential instability, and three-quarters reported vocational instability, suggesting tenuous community living situations. Almost a third had signs of personality disorder and substance use problems. Few significant differences were observed between the two sites in characteristics of visitors. However, there were contextual differences; at the Clarke site, beds were more likely to be unavailable and residents were more likely to make the admission decision.

A total of 81 patients (40 percent) were admitted to inpatient psychiatric units. Of these, 27 were no-bed admissions. No significant differences were found between the two sites in the proportion of admissions and no-bed admissions despite significant differences in bed availability. Overall, the level of agreement between the recommendation of the crisis worker and the final disposition was high. Agreement on admission was 95 percent and on nonadmission was 88 percent. In only 16 cases were the disposition recommendations overturned by a physician. Most of these were by a staff physician rather than a resident (12 physicians compared with four residents). Rates of admission did not vary across level of training of physicians.

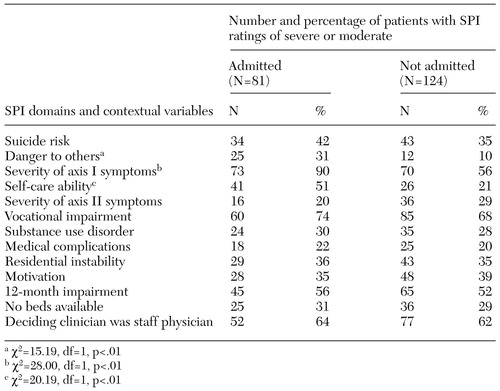

Table 2 summarizes the results of the univariate analyses to identify factors that distinguish admitted and released patients. There were no significant differences in the proportion of patients admitted by each crisis team. Three clinical variables were significantly associated with the decision to admit. Compared with released patients, those who were admitted had significantly higher scores on danger to others, severity of symptoms for axis I disorders, and difficulty with self-care. Bed availability and the training level of the deciding physician were not associated with admission rates.

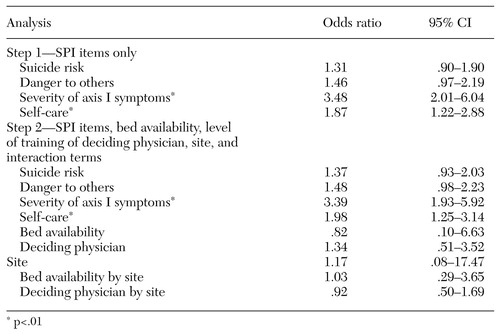

In the logistic regression analyses, the results of which are summarized in Table 3, the severity of axis I disorders and difficulty with self-care were significant in predicting admission in step 1 of the regression. These clinical variables remained significant predictors when contextual variables were added in step 2. None of the contextual variables—site, physician's level of training, or bed availability—influenced the decision to admit, even when interactions were assessed.

Discussion

There is a public perception that bed availability significantly affects whether a patient in need is admitted to inpatient psychiatric units. Our results suggest that this is not the case. Despite the significant difference in bed availability at the two sites in this study, the rates of admission were almost identical, and predictors of admission were consistent: severity of symptoms of axis I disorders and self-care risk. Severity of symptoms of axis I disorders was a particularly sensitive indicator; almost all admitted patients were rated as having moderate or severe axis I symptoms. The exceptions were a small number (three patients) who presented with symptoms of a first psychotic episode. These data suggest that those who are the most ill are appropriately being admitted to hospital.

Danger to self and danger to others were not associated with admission in this regression analysis, although they have been in other studies (2,8,5,10). One explanation for this difference lies in the association between suicidality and personality disorders in our sample (r=.31, p<.01). Breslow and colleagues (22) found that persons with personality disorders were less likely to be admitted to an inpatient unit from a crisis bed, despite high initial rates of suicidal ideation and substance abuse. It may be that suicidality is more consistently predictive of admission among persons who do not have axis II disorders. As far as risk of harm to others is concerned, Roy-Byrne and colleagues (9) found hostility to be a significant predictor of involuntary admission only. Because of the limitations of our sample size, we were unable to explore these potential explanations further. It is unlikely that these findings resulted from the modeling process, because multiple correlations between pairs of the four predictor clinical variables, while the others were controlled for, were minimal (r<.27).

In contrast with earlier studies, our study did not find that physicians in training, particularly those in their first years of residency, were more likely to admit patients to inpatient units. One reason for this finding may be the effectiveness of the clinical teaching unit model of graded responsibility in providing training and support that enables residents, even those in the earlier stages of training, to be comfortable in deciding not to admit a patient. Alternatively, the data were collected only during times when skilled and experienced crisis workers were also on duty, and these clinicians may influence residents' decision making. This notion is supported by the fact that residents are less likely than staff physicians to overturn a crisis worker's recommendation. A comparison of decision making when crisis workers are working and when residents are alone at the site on overnight shifts may clarify this issue. The level of agreement on disposition recommendations between the crisis worker and the physician was high. For the overwhelming majority of cases, admission recommendations appear to be consistent among experienced clinicians, regardless of their discipline.

One of the purposes of the pilot study was to determine the feasibility of introducing a tool for monitoring practice in busy and highly stressful departments. It was evident from the questionnaire completion rate that ongoing feedback is needed to acknowledge the extra work involved and to reinforce its value. It is likely that if such data collection were mandatory, the completion rate would be more consistent. Staff at each site were agreeable to their role; however, a voluntary piece of work added to an already heavy workload inevitably meant that questionnaire completion was accomplished only when sufficient time was available. In considering continued use of the SPI, it would be important to explore why three items on the scale, those related to family functioning and medical compliance, were frequently not completed. These items may be perceived as irrelevant to decision making; alternatively, they may be difficult to assess reliably in a brief period. Periodic interrater reliability checks should also be conducted to maintain the quality of the data.

Several limitations of this pilot study should be noted, particularly those related to its generalizability. The study was conducted with a convenience sample of visitors to emergency psychiatric services in urban teaching hospitals during weekday and evening hours. Although the sample was heterogeneous and similar to those assessed in other emergency psychiatry studies, we were not able to evaluate representativeness. Thus further testing is needed to assess applicability to other inner-city university-affiliated hospitals with a similar standard of evidence-based psychiatric practice. In addition, our findings cannot be generalized to night shifts and to weekends or to emergency services that are not in teaching settings. Given that the Ontario health care system operates under universal access, findings may differ somewhat in environments in which access to beds is subject to other controls, such as in managed care settings. Our sample was too small to enable us to examine whether the model holds for specific subgroups, such as individuals with coexisting axis II or substance use disorders.

Conclusions

Although significant cuts have been made to inpatient psychiatric resources and emergency psychiatry services are increasingly becoming a pressure point in the mental health care system, this study indicated that the people who are in the most need are being admitted to inpatient units. However, a significant number of patients are being held in emergency departments—admitted to "no bed"—rather than going directly to the appropriate inpatient program, a situation that introduces additional stress for both patients and staff. It is encouraging that, despite system pressures, mental health clinicians continue to act in the interests of patients and that the most intensive—and expensive—resources are being used by those who are the most ill.

The Severity of Psychiatric Illness scale appears to be an efficient and discriminating tool for gathering useful information in the emergency psychiatry setting without requiring intensive specialized training. However, if the tool is to be used over time and across multiple settings, interrater reliability should be monitored. Nevertheless, it may be that this kind of evaluation is best undertaken periodically rather than on a continual basis, given the workload pressures under which emergency staff must work.

Given the current pressure on the use of inpatient beds, subsequent studies should seek to identify the services and supports that enable persons with less severe illness or symptoms to avoid hospital admission. Examination of decision making for more difficult-to-manage subgroups, such as persons with severe personality disorders, would help to elucidate best-practice approaches for managing challenging patient populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Mary Rhodes and staff of the St. Michael's Hospital Crisis Intervention Team and Ann Ross and staff of the emergency department of the Clarke site of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto.

Dr. George is a staff psychiatrist on the assertive community treatment team at St. Joseph's Healthcare and assistant clinical professor in the department of psychiatry at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. Ms. Durbin is assistant professor and Dr. Goering is professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of Toronto. Dr. Goering is director, Ms. Sheldon was project coordinator, and Ms. Durbin is a scientist on the Health Systems Research and Consulting Unit of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto. Send correspondence to Dr. George, Hamilton Assertive Community Treatment Team, 401-370 Main Street East, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada L8N 1J6 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Profile of convenience samples of emergency psychiatric patients at two sites in Ontario, Canada, by proportion with ratings of severe or moderate on the Severity of Psychiatric Illness (SPI) scale and context at time of visit

|

Table 2. Univariate relationship between Severity of Psychiatric Illness (SPI) ratings, contextual variables, and hospital admission

|

Table 3. Results of logistic regression analyses indicating the relative contributions of clinical variables according to the Severity of Psychiatric Illness (SPI) scale and of contextual variables to the decision to admit

1. Health Canada: Best Practices in Mental Health Reform. Ottawa, Health Canada, 1997Google Scholar

2. Way BB, Banks S: Clinical factors related to admission and release decision in psychiatric emergency services. Psychiatric Services 52:214-218, 2001Link, Google Scholar

3. Harris JS: Development, use, and evaluation of clinical practice guidelines. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 39:23-24, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Bengelsdorf H, Levy L, Emerson R, et al: A crisis triage rating scale: brief dispositional assessment of patients at risk of hospitalization. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 172:424-430, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Lyons J, Stutesman J, Neme J, et al: Predicting psychiatric emergency admissions and hospital outcome. Medical Care 35:791-800, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Way B, Evans M, Banks S: Factors predicting referral to inpatient or outpatient treatment from psychiatric emergency services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:703-708, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Slagg NB: Characteristics of emergency room patients that predict hospitalization or disposition to alternative treatments. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:252-256, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Segal SP, Egley L, Watson MA, et al: The quality of psychiatric emergency evaluations and patient outcomes in county hospitals. American Journal of Public Health 85:1429-1431, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Roy-Byrne P, Russo J, Rabin L, et al: A brief medical necessity scale for mental disorders: reliability, validity, and clinical utility. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 24:412-424, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Rabinowitz J, Massad A, Fennig S: Factors influencing disposition decisions for patients seen in a psychiatric emergency service. Psychiatric Services 46:712-718, 1995Link, Google Scholar

11. Mattioni T, Di Lallo D, Roberti R, et al: Determinants of psychiatric inpatient admission to general hospital psychiatric wards: an epidemiological study in a region of central Italy. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 34:425-431, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Way B, Evans M, Banks S: Factors predicting referral to inpatient or outpatient treatment from psychiatric emergency services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:703-708, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

13. Streiner DL, Goodman JT, Woodward C: Correlates of the hospitalization decision: a replicative study. Canadian Journal of Public Health 66:411-415, 1975Medline, Google Scholar

14. Fichtner C, Flaherty J: Emergency psychiatry training and the decision to hospitalize. Academic Psychiatry 17:585-586, 1993Google Scholar

15. Baxter S, Chodorkoff B, Underhill R: Psychiatric emergencies: dispositional determinants and the validity of the decision to admit. American Journal of Psychiatry 124:1542-1548, 1968Link, Google Scholar

16. Meyerson A, Moss J, Belville R, et al: Influence of experience on major clinical decisions. Archives of General Psychiatry 36:423-427, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Lyons J, Colletta J, Devens M: Validity of Severity of Psychiatric Illness rating scale in a sample of inpatients on a psychogeriatric unit. International Psychogeriatrics 7:407-416, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Roy-Byrne PP, Russo J: Interrater agreement among psychiatrists regarding emergency psychiatric assessments [letter]. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1840-1841, 1999Link, Google Scholar

19. Lyons J, O'Mahoney M, Doheny K, et al: The prediction of short-stay psychiatric inpatients. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 23:17-25, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Lyons J, O'Mahoney M, Miller S, et al: Predicting readmission to the psychiatric hospital in a managed care environment: implications for quality indicators. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:337-340, 1997Link, Google Scholar

21. Norman G, Streiner D: Biostatistics: The Bare Essentials, 2nd ed. Toronto, Decker, 2000Google Scholar

22. Breslow R, Klinger B, Erickson B: Crisis hospitalization on a psychiatric emergency service. General Hospital Psychiatry 15:307-315, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar