Hospitalization of Patients With Cocaine and Amphetamine Use Disorders From a Psychiatric Emergency Service

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: Among the illicit stimulants, cocaine and amphetamines are the most widely abused. Although these drugs have similar psychoactive properties and routes of administration, their duration of action and mechanism of action are different, as are the psychiatric problems that accompany their use. The authors explored whether these differences and results of urine drug testing were associated with differences in use of psychiatric inpatient services. METHODS: The records of 2,357 patients admitted to a large county psychiatric emergency service were examined to determine whether patients admitted for amphetamine-related or cocaine-related disorders differed in rates of transfer to an inpatient psychiatric ward or in length of stay on the ward after transfer. The authors also examined whether positive or negative results of urine drug screens predicted transfer or length of stay. RESULTS: Patients with amphetamine-related disorders were more than a third more likely than patients with cocaine-related disorders to be transferred to the inpatient ward. Patients with negative urine screens were a third more likely than those with positive screens to be transferred and stayed slightly longer on the ward after transfer. Patients with cocaine-related disorders stayed slightly longer on the ward than patients with amphetamine-related disorders. CONCLUSIONS: Patients with amphetamine-related disorders have higher rates of psychiatric hospitalization than patients with cocaine-related disorders. Diagnostic uncertainty and other factors may also influence transfer rates and subsequent length of stay.

Among the illicit stimulants, cocaine and the amphetamines are the most widely abused. Cocaine use has been widespread but decreasing since the early 1990s. However, use of amphetamines, particularly methamphetamine, has grown in the past decade, spreading eastward from its endemic centers in the western and southwestern United States (1,2,3). Cocaine and amphetamines both cause psychiatric disorders. In the text revision of DSM-IV, they have essentially identical diagnostic criteria for intoxication and withdrawal, and the same classification of other disorders induced by the substances—psychotic, mood, anxiety, sleep, and sexual disorders—is used for both drugs (4).

Cocaine is an organic extract of the coca leaf. The amphetamines are synthetic and, until recent enactment of corrective legislation, could be produced from reagents purchased in drugstores, hardware stores, and chemical supply houses. Both cocaine and amphetamines are commonly snorted, smoked (vaporized), or injected.

Amphetamines have a longer duration of action than cocaine (eight to 12 hours compared with one to three hours) and different mechanisms of action. Both drugs block the reuptake of synaptic dopamine via the dopamine transporter, but amphetamines also directly affect intracellular vesicular dopamine release and have a greater impact on serotonin and norepinephrine release (5,6,7). Neuronal toxicity in rodent models differs among the various stimulants (8).

Amphetamine withdrawal lasts longer than cocaine withdrawal, and amphetamines are generally held to be more psychotogenic, possibly even causing a spontaneously relapsing psychosis that has not been reported with cocaine use (9,10). However, it is generally assumed that substance-induced phenomena remit over time with abstinence. In studies of cocaine-dependent individuals receiving inpatient treatment, 29 of 55 participants (53 percent) reported having transient cocaine-related psychosis lasting less than 24 hours (11), and 34 of 50 participants (68 percent) reported cocaine-induced paranoia lasting less than 72 hours (12). Morgan (13) reported a similar incidence of psychotic symptoms and paranoia in community samples of 450 moderate to heavy methamphetamine users. In a study comparing 224 cocaine and 500 methamphetamine users receiving inpatient treatment, Rawson and associates (14) reported that methamphetamine users endorsed significantly more items related to depression, suicidal thoughts, and hallucinations than cocaine users but had similar levels of paranoia and previous psychiatric treatment in general. In a community sample of drug users in London, England, Williamson and colleagues (15) found that amphetamine users had significantly more serious adverse effects than cocaine users and that a greater proportion of amphetamine users reported paranoia, depression, mood swings, anxiety, and irritability. Earlier studies described amphetamine psychosis and paranoia lasting 48 to 72 hours after cessation of use and some signs of thought disorder persisting at least a week (16,17).

Both cocaine and amphetamine use are related to the use of general medical and psychiatric emergency services (18,19,20,21). Harris and Batki (22) studied 19 patients who presented to psychiatric emergency services with amphetamine- or cocaine-induced psychotic disorder. They observed a positive correlation between total length of psychiatric hospital stay and both the general psychopathology score and the negative score on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale. Presumably because of the small sample, the investigators did not differentiate between amphetamine- and cocaine-induced disorders.

Claassen and associates (23) noted higher rates of psychiatric hospitalization for patients with positive results on urine drug tests who were seen in psychiatric emergency services. However, the sample consisted of patients who were using any drug, including alcohol, and was limited to patients who presented with psychosis. Schiller and associates (24,25) studied 392 polydrug users hospitalized after referral from an urban county psychiatric emergency service. They found no direct relationship between positive and negative results on urine drug tests and length of inpatient stay but noted greater rates of hospitalization for patients whose drug results were not available at the time of mandatory disposition.

We undertook this retrospective study to further investigate the relationships between type of stimulant-related disorder and use of psychiatric services. We expected that the use of services in our sample of patients admitted to a 24-hour county psychiatric emergency service, as measured by rates of transfer to an inpatient unit and subsequent length of stay, would be higher for patients with amphetamine-related disorders than those with cocaine-related disorders. We also expected greater service use by patients with positive urine drug screens than for those with negative screens.

Methods

Sacramento County occupies about 1,000 square miles in the north of California's Central Valley. Its 1996 population of 1,132,100 was ethnically diverse—66 percent non-Hispanic white, 13 percent Hispanic, 10 percent African American, and 10 percent Asian—and the median household income was $32,300. The Sacramento County Mental Health Treatment Center is a freestanding 100-bed inpatient psychiatric facility and is the sole such facility for county Medicaid and uninsured patients. The department of psychiatry of the University of California, Davis, provides psychiatric staff under an affiliation agreement.

The psychiatric crisis unit is a 19-bed unit within the treatment center that serves as its intake facility. The unit is the sole facility to which county law enforcement officers can bring people for involuntary psychiatric evaluation. The unit also functions as the psychiatric emergency referral center for most of the general hospital emergency departments in the county. All patients in the unit meet California's criteria for involuntary psychiatric hospitalization at the time of admission. State regulations permit a maximum stay of 23 hours before either discharge or transfer to an inpatient unit. Decisions to discharge patients from the psychiatric crisis unit or transfer them to the inpatient ward are made by the unit's psychiatrist-led multidisciplinary treatment team.

All patients admitted to the psychiatric crisis unit undergo at least three unstructured clinical interviews, conducted by the team social worker or psychologist, the unit nurse, and the staff psychiatrist. Patient data are entered into the county's computerized Client Access Tracking System (CATS). The database include dates of admission to and discharge from the unit, dates of transfer to and discharge from the inpatient ward if applicable, information on demographic characteristics and payer source, and a single DSM-III-R or DSM-IV axis I or axis II diagnostic code for each admission to the psychiatric crisis unit. The coded diagnosis is the one that the treating clinicians judge to be primarily responsible for the patient's admission. All patients admitted to the psychiatric crisis unit are asked to provide a urine sample for drug testing. The testing consists of latex agglutination immunoassays for benzoylecgonine, the major metabolite of cocaine, and for amphetamine, the methamphetamine metabolite (26,27).

All 21,615 persons aged 18 years or older admitted to the psychiatric crisis unit from July 1993 through June 1997 were potential subjects. Data on all admissions for which diagnostic codes were recorded for substance-related disorders were extracted from the CATS database. Two of the authors (MHL and LB) and senior medical records staff reviewed charts to clarify substance-specific diagnoses for nonspecific DSM codes (for example, the 292.xx series) and to extract urine drug screening data.

In 132 charts the results of the urine drug screen were incongruent with the substance-related disorder codes, and these data were excluded. Because the urine drug screen result was to be a predictor variable, 453 admissions were also excluded because patients refused to take a drug test. Thus 2,357 patients were eligible for the study. Refusal to take a drug test appeared to be unrelated to age, sex, and race or ethnicity. However, a greater proportion of patients with amphetamine-related disorder refused the test than did patients with cocaine-related disorder (18 percent compared with 11 percent; χ2=17.35, df=1, p<.001).

We examined differences between patients with amphetamine-related disorders and those with cocaine-related disorders in transfer rates from the psychiatric crisis unit to the inpatient psychiatric ward and in length of stay on the ward after transfer. In both sets of analyses, chi square tests were used to examine univariate differences between admissions for amphetamine-related disorders and those for cocaine-related disorders. The multivariate analysis of transfer rates involved logistic regressions, which included as predictors, in addition to diagnosis, demographic characteristics and urine drug screen results (positive or negative). Ordinary least-squares regression was used for multivariate analysis examining predictors of length of inpatient stay.

Given that amphetamine is the longer acting of the two drugs, we hypothesized that patients with amphetamine-related disorders would be more likely than those with cocaine-related disorders to be transferred to the inpatient ward and, after transfer, would stay longer. We also hypothesized that both higher transfer rates and longer stays would be related to positive urine drug screen results, because a positive result might be a predictor of longer duration of drug-related symptoms.

Results

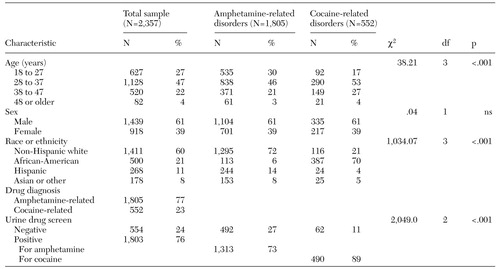

Table 1 lists demographic and other characteristics of the patients. The modal age of patients was in the mid-30s. The sample included more men than women, and non-Hispanic whites outnumbered other racial and ethnic groups. More than three-quarters of the sample had a diagnosis of amphetamine-related disorders, and the remainder had a diagnosis of cocaine-related disorders. Slightly more than three-quarters had positive results for amphetamine or cocaine on the urine drug screen. A comparison of patients with amphetamine-related disorders and cocaine-related disorders revealed identical proportions of men and women but differences in age and racial and ethnic composition. A somewhat greater proportion of patients with amphetamine-related disorders were in their 20s compared with patients with cocaine-related disorders. Non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics were much more likely to have amphetamine-related disorders, and African Americans were far more likely to have cocaine-related disorders. A diagnosis of cocaine-related disorders was substantially more likely to be accompanied by positive results on the urine drug screen than was a diagnosis of amphetamine-related disorders.

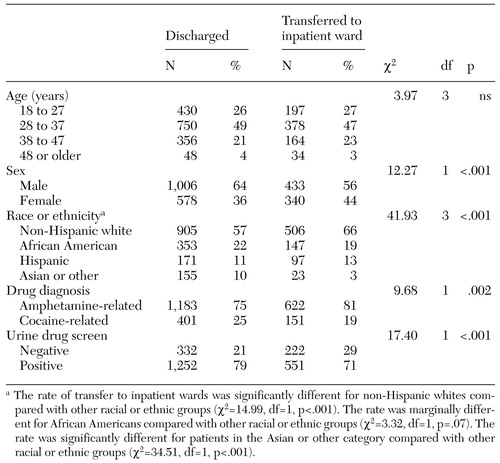

Table 2 lists transfer rates from the psychiatric crisis unit to the inpatient ward by demographic and diagnostic characteristics. Age was not a significant predictor of transfer, but women were more likely than men to be transferred. Transfers were more likely for non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, and African Americans than for Asians. As expected, transfer rates were higher for patients with amphetamine-related disorders than for patients with cocaine-related disorders. However, contrary to expectation, patients with negative urine drug screen results were more likely to be transferred.

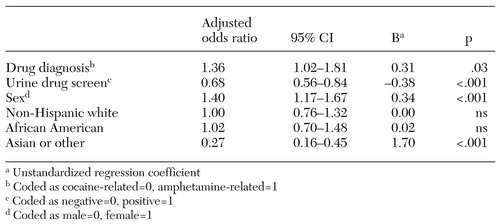

Results of the multiple logistic regression of factors affecting transfer rates are summarized in Table 3. The likelihood of being transferred to the inpatient ward was more than 35 percent higher for patients with amphetamine-related disorders than for those with cocaine-related disorders. Patients with positive urine drug screen results were about 70 percent as likely to be transferred as patients with negative results. Women were 40 percent more likely to be transferred. Non-Hispanic whites and African Americans were no more likely to be transferred, and Asians were far less likely to be transferred.

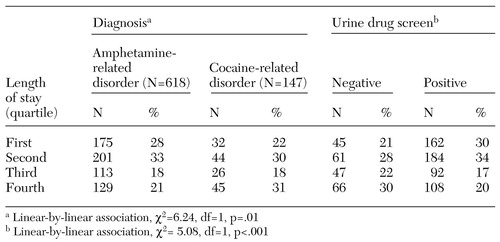

Of the 773 patients transferred to the inpatient ward (median ward length of stay=2 days, mean±SD=4.5±10.8 days), eight whose length of stay was more than three standard deviations above the mean were excluded from the analyses. The resulting length of stay (median=2 days, mean±SD=3.5±3.71 days) was log transformed to correct its somewhat skewed distribution. The 765 patients were divided into four quartiles, containing 27 percent, 32 percent, 18 percent, and 23 percent, from shortest to longest stay. Table 4 summarizes lengths of stay on the inpatient psychiatric ward after transfer from the psychiatric crisis unit, by drug diagnosis and urine drug screen results.

Univariate chi square analyses showed no association between demographic characteristics and length of stay. Patients with cocaine-related disorders and patients with negative drug screen results were more likely to have longer stays. Ordinary least-squares regression analysis of the joint effects of diagnosis and drug screen results revealed that both variables were modest independent predictors of length of stay. The unstandardized regression coefficients (B coefficients) for diagnosis (cocaine=0, amphetamine=1) and drug screen (negative=0, positive=1) were −.116 (p<.001) and −.121 (p<.001). These values indicated that patients with cocaine-related disorders were in treatment a fractional day longer than those with amphetamine-related disorders and that patients with negative drug test results were likely to remain on the ward somewhat longer.

Discussion

We studied the disposition of patients with amphetamine-related and cocaine-related disorders who were seen at a psychiatric emergency service, examining transfer rates for inpatient psychiatric hospitalization and subsequent length of stay. The demographic characteristics of our sample were similar to those that have been reported both locally and regionally for methamphetamine and cocaine abusers (14,25,28,29). Our study analyzed data from a psychiatric emergency service and an inpatient psychiatric ward and thus improved on studies that relied on self-report to determine differences in use of services.

Patients with amphetamine-related disorders had significantly higher rates of transfer to an inpatient psychiatric ward than patients with cocaine-related disorders. Patients are transferred from the psychiatric crisis unit to the inpatient ward when their condition does not improve sufficiently during their 23-hour stay in the crisis unit to allow them to be safely discharged. Although our data did not allow us to evaluate syndrome severity on other grounds, all patients admitted to the unit have symptoms severe enough to warrant hospitalization in a locked setting. Thus the average patient with amphetamine-related disorders may not improve as quickly as the average patient with cocaine-related disorders or may present to the psychiatric crisis unit with more severe symptoms.

When viewed in conjunction with the findings that psychiatric symptoms and use of psychiatric services are higher among arrestee amphetamine abusers or those receiving substance abuse treatment, our findings support the clinical observation that use of methamphetamine is associated with greater psychiatric morbidity than use of cocaine (14,24,28,29).

The finding of lower rates of transfer for Asians is consistent with results of other studies that examined use of inpatient psychiatric services by Asians (30,31,32,33,34). Snowden and Cheung (34) hypothesized that lower rates of psychiatric hospitalization among Asians may be due to several factors: differences in the prevalence of psychiatric illnesses or their symptoms, differential stigma attached to mental illness, capacity to tolerate or support dysfunctional family members in the ethnic community, and bias in the behavior of mental health providers. Our conversations with experts familiar with both the local community mental health environment and the various local Asian communities suggest that at least several of these factors may be relevant in our study population. However, verifying these hypotheses would require further study.

The women in our sample had a higher rate of transfer. Women substance abusers tend to have more severe psychosocial problems, more comorbid psychiatric disorders, and more severe substance use disorders when presenting for treatment than men (35,36,37,38,39). Our data did not permit us to conclude that these factors applied to our sample, nor can we rule out gender bias in hospitalization or discharge decisions.

The association of negative drug screen results—the absence of the diagnosed substance in the patient's urine—with a higher likelihood of transfer to the inpatient ward (Table 3) is not consistent with our hypothesis of a higher rate of transfer among patients with positive drug screen results. Several of the attending psychiatrists who treated patients on the psychiatric crisis unit during our study period acknowledged a tendency to hospitalize patients for the purpose of clarifying diagnostic dilemmas when clinically warranted. Furthermore, they suggested that patients who had negative urine drug screen results but whose symptoms were attributed to drug use would be more likely to be hospitalized for the purpose of clarifying the diagnosis. This tendency may be analogous to Schiller and associates' finding of higher transfer rates among patients with pending drug screen results (24).

Our analyses showed that a diagnosis of cocaine-related disorder was associated with a slightly longer inpatient stay, as was a negative urine drug screen, regardless of diagnosis. These findings are inconsistent with our hypothesis that both patients with amphetamine-related disorders and patients with positive urine drug screen results would have longer hospitalizations. Although the effect sizes are small and may not be clinically meaningful, these findings bear further study.

Several limitations of our study should be mentioned. In the CATS database, only one psychiatric diagnosis is recorded for each admission, which limits the opportunity to examine the effects of comorbid disorders on patient disposition. However, we may reasonably assume that this limitation affects patients with both drug use disorders similarly and thus had a less direct impact on the comparisons between the two groups.

Also, our study relied on clinical diagnoses, not those based on standardized instruments. However, the demands of administering a standardized instrument that is meaningfully better than a consensus diagnosis by three clinicians to patients who are in crisis within 23 hours of their admission are such that its benefits would likely be outweighed by the smaller number of patients who could tolerate it. Finally, it would be advantageous to have additional information about the subjects' symptoms, such as psychosis, suicidality, or aggressiveness. Such data would have added richness and detail to this type of study, but whether they would change the basic findings is unclear.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that methamphetamine causes greater psychiatric morbidity than cocaine, as measured by higher rates of transfer from a psychiatric emergency service to an inpatient psychiatric ward. Other factors, some perhaps related to physicians' concerns about diagnostic uncertainty and others yet to be identified, contribute to determining the duration of inpatient stay after transfer. We speculate that as methamphetamine abuse becomes more widespread, psychiatric emergency services that are accustomed to dealing primarily with cocaine-related disorders will see more patients presenting with amphetamine-related disorders, and these patients are likely to require greater use of psychiatric inpatient services.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grant DA-10641 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and by the Sacramento County Division of Mental Health.

Dr. Leamon, Dr. Canning, and Dr. Benjamin are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and Dr. Gibson with the department of internal medicine at the University of California, Davis. Send correspondence to Dr. Leamon at the University of California, Davis, Medical Center, Department of Psychiatry, 2230 Stockton Boulevard, Sacramento, California 95817 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics and diagnostic grouping of 2,357 patients with amphetamine- or cocaine-related disorders in a psychiatric emergency service who received urine drug screening tests

|

Table 2. Comparison by demographic and clinical characteristics of dispositions of 2,357 patients with amphetamine- or cocaine-related disorders in a psychiatric emergency service

|

Table 3. Results of the multiple logistic regression of factors affecting transfer rates from a psychiatric emergency service to an inpatient psychiatric unit, with adjustment for demographic characteristics, for 2,357 patients with amphetamine- or cocaine-related disorders

|

Table 4. Duration of inpatient psychiatric hospitalization, in quartiles, by drug diagnosis and by urine drug screen results for 765 patients transferred from a psychiatric emergency service to an inpatient psychiatric unit with amphetamine- or cocaine related disorders

1. Summary of Findings from the 1998 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (Cocaine). Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, Aug 1999. Available at http://www.samhsa.gov/oas/NHSDA/98SummHtml/NHSDA98Summ-05.htm#P369_29947Google Scholar

2. Trends in Primary Substance of Abuse: Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS), 1992-1997. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, Aug 1999. Available at http://wwwdasis.samhsa.gov/teds97/id11_m.htmGoogle Scholar

3. Methamphetamine: A Dangerous Drug, A Spreading Threat, in National Drug Control Strategy, 1999. Washington, DC, Office of National Drug Control Policy, 1999. Available at http://www.ncjrs.org/ondcppubs/publications/policy/99ndcs/ii-h.htmlGoogle Scholar

4. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, text revision. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000Google Scholar

5. Munzar P, Laufert M, Kutkat S, et al: Effects of various serotonin agonists, antagonists, and uptake inhibitors on the discriminative stimulus effects of methamphetamine in rats. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 291:239-250, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

6. Segal DS, Kuczenski R: Behavioral pharmacology of amphetamine, in Amphetamine and Its Analogs: Psychopharmacology, Toxicology, and Abuse. Edited by Cho AK, Segal DS. San Diego, Calif, Academic Press, 1994Google Scholar

7. Fleckenstein A, Haughey H, Metzger R, et al: Differential effects of psychostimulants and related agents on dopaminergic and serotonergic transporter function. European Journal of Pharmacology 382:45-49, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Ellison G, Switzer RC: Dissimilar patterns of degeneration in brain following four different addictive stimulants. Clinical Neuroscience and Neuropsychology 5:17-20, 1993Google Scholar

9. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment: Treatment for Stimulant Use Disorders. Treatment Improvement Protocol 33. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 1999Google Scholar

10. Yui K, Goto K, Ikemoto S, et al: Monoamine neurotransmitter function and spontaneous recurrence of methamphetamine psychosis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 81:415-429, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Brady KT, Lydiard RB, Malcolm R, et al: Cocaine-induced psychosis. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 52:509-512, 1991Medline, Google Scholar

12. Satel S, Southwick S, Gawin F: Clinical features of cocaine-induced paranoia. American Journal of Psychiatry 148:495-498, 1991Link, Google Scholar

13. Morgan P: Researching Hidden Communities: A quantitative comparative study of methamphetamine use in three sites, in Epidemiologic Trends in Drug Abuse. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1994Google Scholar

14. Rawson R, Huber A, Brethen P, et al: Methamphetamine and cocaine users: differences in characteristics and treatment retention. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 32:233-238, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Williamson S, Gossop M, Powis B, et al: Adverse effects of stimulant drugs in a community sample of drug users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 44:87-94, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Ellinwood EH: Amphetamine psychosis: a multidimensional process. Seminars in Psychiatry 1:208-226, 1969Google Scholar

17. Ellinwood EH: Amphetamine psychosis: I. description of the individuals and process. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorders 144:273-283, 1967Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Cunningham JK, Thielemeir MA: Amphetamine-Related Emergency Admissions: Trends and Regional Variations in California (1985-1994). Irvine, Calif, Public Statistics Institute, 1996Google Scholar

19. Cunningham JK, Thielemeir MA, Hicks DA: Cocaine-Related Emergency Admissions: Trends and Regional Variations in California (1985-1994). Irvine, Calif, Public Statistics Institute, 1996Google Scholar

20. Leamon MH, Canning RD, Benjamin L: The impact of amphetamine-related disorders on community psychiatric emergency services:1993-1997. American Journal on Addictions 9:70-78, 2000Google Scholar

21. Mid-Year 1999 Preliminary Emergency Department Data from the Drug Abuse Warning Network. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 2000Google Scholar

22. Harris D, Batki SL: Stimulant psychosis: symptom profile and acute clinical course. American Journal on Addictions 9:28-37, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Claassen C, Gilfillan S, Orsulak P, et al: Substance use among patients with a psychotic disorder in a psychiatric emergency room. Psychiatric Services 48:353-358, 1997Link, Google Scholar

24. Schiller M, Shumway M, Batki S: Utility of routine drug screening in a psychiatric emergency setting. Psychiatric Services 51:474-478, 2000Link, Google Scholar

25. Schiller M, Shumway M, Batki S: Patterns of substance use among patients in an urban psychiatric emergency service. Psychiatric Services 51:113-115, 2000Link, Google Scholar

26. Roche Diagnostic Systems: ONTRAK TesTstik for cocaine, package insert, 1997Google Scholar

27. Cho AK, Kumagai Y: Metabolism of amphetamine and other arylisopropylamines, in Amphetamine and Its Analogs: Psychopharmacology, Toxicology, and Abuse. Edited by Cho AK, Segal DS. San Diego, Calif, Academic Press, 1994Google Scholar

28. Kalechstein AD, Newton TF, Longshore D, et al: Psychiatric comorbidity of methamphetamine dependence in a forensic sample. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 12:480-484, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Gonzalez Castro F, Barrington E, Walton M, et al: Cocaine and methamphetamine: differential addiction rates. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 14:390-396, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Coid J, Kahtan N, Gault S, et al: Ethnic differences in admissions to secure forensic psychiatry services. British Journal of Psychiatry 177:241-247, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Commander M, Cochrane R, Sashidharan S, et al: Mental health care for Asian, black, and white patients with non-affective psychoses: pathways to the psychiatric hospital, in-patient and after-care. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 34:484-491, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Crawford K, Fisher W, McDermeit M: Racial/ethnic disparities in admissions to public and private psychiatric inpatient settings: the effect of managed care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 26:101-109, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Hu T, Snowden L, Jerrell J, et al: Ethnic populations in public mental health: services choice and level of use. American Journal of Public Health 81:1429-1434, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Snowden L, Cheung F: Use of inpatient mental health services by members of ethnic minority groups. American Psychologist 45:347-355, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Brady K, Grice D, Dustan L, et al: Gender differences in substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:1707-1711, 1993Link, Google Scholar

36. Gearon J, Bellack A: Sex differences in illness presentation, course, and level of functioning in substance-abusing schizophrenia patients. Schizophrenia Research 43:65-70, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Grilo C, Martino S, Walker M, et al: Psychiatric comorbidity differences in male and female adult psychiatric inpatients with substance use disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry 38:155-159, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Weiss R, Martinez-Raga J, Griffin M, et al: Gender differences in cocaine dependent patients: a 6 month follow-up study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 44:35-40, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Alexander M: Women with co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: an emerging profile of vulnerability. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:61-70, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar