Work Rehabilitation and Patterns of Substance Use Among Persons With Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The aim of this study was to identify patterns of substance use among participants in work rehabilitation, to identify symptom patterns associated with substance use, and to assess the impact of substance use on work rehabilitation outcomes. METHODS: Addiction Severity Index interviews were conducted and Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale ratings were obtained at the start of the study and again five months and 12 months later for 220 patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who were already enrolled in a study of work rehabilitation. RESULTS: Eighty percent of the participants met Addiction Severity Index criteria for lifetime substance use, but 75 percent were abstinent at intake. During the 12-month follow-up period, abstinence rates remained above 66 percent. Participants with a lifetime history of cocaine use were more likely to return to substance use. The type of substance used was also related to distinct symptom patterns. Participants with past cocaine use had more severe hostility symptoms and less severe negative symptoms. No significant relationships were found between lifetime or current substance use and participation in the work rehabilitation program. CONCLUSIONS: Even though a high rate of lifetime substance use was observed in this sample, most participants were in stable remission of substance use throughout the one-year study. Substance use and work participation appeared to be semiautonomous: substance use did not directly affect work participation, and work participation did not directly affect substance use.

Since the 1989 publication of the seminal article by Lehman and colleagues on psychiatric and substance abuse syndromes, which was recently reprinted in this journal (1), substance use and abuse have been widely recognized as commonly occurring problems among persons with schizophrenia. Dixon and colleagues (2) have reported some good news about substance use in this population. They found a dramatic remission of substance use over time in a prospective study that began with an episode of hospitalization. Using the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (3), they found that 50 to 75 percent of the participants in their one-year study achieved stable remission. This finding does not detract from the seriousness of substance abuse and its impact on the course of schizophrenia, but it brings home the point that an individual's substance use may decrease over time.

At our work rehabilitation center for people who have schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, we collected information about substance use among our participants in a manner identical to that of Dixon and colleagues (2). We wanted to compare the lifetime rates in our sample with their findings. We also wanted to learn how a lifetime history of substance use and active substance use at intake might relate to success in work rehabilitation over a one-year period. We hypothesized that being involved in work rehabilitation might reduce substance use. These questions are important because substance use and abuse are so common among persons with schizophrenia.

Although estimates of prevalence vary widely, reports suggest that about 50 percent of people with schizophrenia meet criteria for a diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence at some time in their life and that 20 to 40 percent meet criteria for current or recent abuse (4). Alcohol is the most commonly used substance among people with schizophrenia, with estimates ranging from 12.3 percent to 50 percent (5,6). Estimates of the use of cannabis in this population have ranged from 12.5 percent to 35.8 percent (7,8). Estimates of the use of stimulants, including cocaine, are similar, ranging from 11.3 percent to 31 percent (8,9).

There are a number of theories about why people with schizophrenia have higher rates of substance abuse than the general population. One widely held theory is that nonprescribed drugs are used to self-medicate depression, anxiety, and negative symptoms. People with negative symptoms may use stimulants, such as cocaine, to self-medicate anergia (10). However, Lysaker and colleagues (11) found that patients with schizophrenia who used cocaine had fewer negative symptoms than did patients with schizophrenia who had no history of substance abuse. These authors speculated that people with severe negative symptoms might not have the necessary social skills to obtain cocaine, even if they live in social environments that promote its use.

In contrast with theories that relate substance use to the characteristics of a patient's illness, there is evidence that people with schizophrenia use and abuse drugs for many of the same reasons that people in the general population do—to enjoy the "buzz," to make it easier to socialize with others, and to provide relief from emotional distress (12). Mueser and associates (13) conducted a literature review and concluded that there was scant research support for the self-medication hypothesis. They pointed out that risk factors such as poverty, unemployment, and deviant peers were more likely to predict substance abuse among persons with mental illness.

Given that substance abuse has been associated with these environmental factors, it is reasonable to believe that a work rehabilitation program that provides daily structured activity, reduces the chronic stress of poverty, and increases positive social contacts might favorably affect substance use. This view gains support from some of our previously reported findings (14,15,16) that paid work activity provides clinical benefits for people who have schizophrenia, including less severe symptoms, higher income, and a better quality of life. In particular, we found that working improved the participants' motivation, sense of purpose, and enjoyment of life as well as the number and quality of their interpersonal relationships.

Estimates of substance abuse remission rates among individuals with chronic mental illness who do not enter work rehabilitation vary widely. Several researchers have reported that few patients achieve stable remission (17,18), in contrast with Dixon and colleagues (2), who, as noted above, found a significant reduction in substance use and abuse over time. Studies of the relationship between remission and relapse and the clinical course of schizophrenia suggest that patients who have a history of substance abuse have a worse course marked by higher rates of hospitalization (19) as well as higher suicide rates (20). However, it is unclear whether these differences in clinical course are related to exacerbation of psychosis or to other effects of substance use, such as increased aggression and bizarre behavior (21).

To our knowledge, no studies of the relationship between substance use and the course of work rehabilitation have been published. Nevertheless, rehabilitation programs have always had to deal with substance use. One approach has been to use contingencies for relapse to discourage drug use. Participants may be suspended from participation in the program because of drug use and allowed reentry only after some predetermined period of abstinence. For example, one work program at our facility requires a year of abstinence before the person can return to work. An experimental approach that has been tried by a few rehabilitation programs has been to reward participants—for example, with cash payments—for abstinence, most commonly measured by negative results of toxicology tests (22).

However, by far the most common approach is to exclude active substance abusers from work rehabilitation programs until they have successfully completed substance abuse treatment. This notion of consecutive treatments assumes that untreated substance use or abuse will disrupt work rehabilitation or that participation in work rehabilitation will undermine substance abuse treatment.

Some clinicians may believe that providing paid work to a substance-abusing person who has schizophrenia will actually enable the use of substances by contributing to the patient's denial and by giving the patient the financial means to obtain more drugs or alcohol. This belief provided us with a hypothesis to be tested with our work rehabilitation outcome data. Such testing was possible because our study did not exclude substance abusers or require that they receive treatment for substance abuse before entry into the program.

Our study had three purposes: to determine the frequency of substance use and history of abuse in a sample of persons with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who were seeking work rehabilitation and to determine abstinence rates, to test the hypothesis that symptoms are differentially related to the types of drugs used and the course of their use, and to prospectively assess the predictive value of past and current substance use on the course of work rehabilitation and the impact of work rehabilitation on rates of substance use.

We hypothesized that past substance use and abstinence rates at intake would be roughly comparable to those found by Dixon and colleagues (2). We also hypothesized that symptom profiles would support our previous finding that persons who abuse cocaine have more severe hostility symptoms and less severe negative symptoms. We hypothesized that substance use at intake would not be closely related to work rehabilitation outcomes and that participation in work rehabilitation would increase concurrent abstinence rates.

Methods

Participants

A total of 220 patients with a DSM-III-R diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder from the psychiatry service at a Veterans Affairs medical center were invited to participate in the study, which was conducted between 1989 and 1998. Diagnoses were made after completion of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III (SCID) (23). Participants completed intake measures as part of a study of the impact of work rehabilitation for people with severe mental illness (14). Patients were eligible for inclusion in the study if they were deemed clinically stable—that is, had had no housing changes, alterations in psychiatric medication, or hospitalizations in the 30 days before intake—and did not have known neurological disease or a history of seizures or significant head trauma.

Instruments

Addiction Severity Index. The ASI is a structured interview instrument that yields information about the severity of lifetime and recent (previous 30 days) drug and alcohol use. Specifically, participants report the number of months in their lifetime that they used each substance at least three times a week to the point of intoxication. The Department of Veterans Affairs uses the ASI as its standard instrument for assessing substance abuse.

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (24) is a 30-item scale based on a structured interview and a chart review. The PANSS items constitute three rationally derived categories of symptoms —positive, negative, or general—that are rated on degree of severity. This study used the five-factor analytically derived scores of Bell and colleagues (25): positive, negative, cognitive disorganization, hostility, and emotional discomfort. Good to excellent interrater reliability has been found for scale scores and for most individual items (26). To check for drift in interrater reliability, our raters conducted 20 interviews with participants from the study sample. Reliabilities were improved from our previous published reports: all items were in the good range, and all scales were in the excellent range.

Procedures

The study was approved by the human subjects subcommittee of the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System. After written informed consent was obtained, diagnoses of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were determined with use of the SCID. Participants completed the PANSS and the ASI as part of a comprehensive intake battery. Interviews were conducted by trained master's- and doctoral-level clinicians. Participants were categorized into one of four groups on the basis of information obtained at intake with the ASI: use of cocaine alone or with other substances, use of alcohol only, substance use other than cocaine or alcohol, and no substance use. To be categorized as having a history of substance use, participants had to have had an episode of at least two months during which they were using a drug of abuse or becoming intoxicated with alcohol on at least three days of every week.

After completing all intake requirements, participants were offered a job placement as part of a study of work rehabilitation and schizophrenia (14). The PANSS and the ASI were administered to participants again five months later—toward the end of the active program—and 12 months later.

Analyses were conducted to determine the relationship between symptoms and substance use category, to determine whether substance use had a detectable effect on participation in the work program, and to determine whether recent substance use was related to the number of hours of work and the number of weeks of participation in the program.

Results

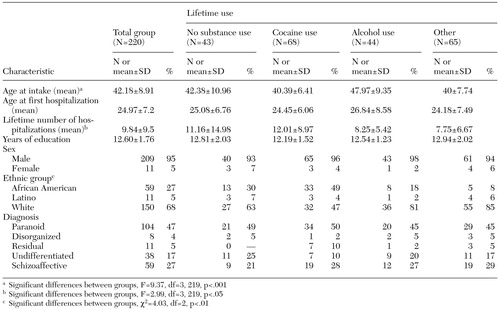

Of the initial 220 participants, 43 (20 percent) had no history of substance use, and 177 (80 percent) had significant lifetime substance use. Sixty-eight participants (31 percent) had a history of use of cocaine, 44 (20 percent) had a history of alcohol use only, and 65 (30 percent) had a history of use of other substances excluding cocaine and alcohol. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the entire sample and of the subgroups are presented in Table 1.

Analysis of variance revealed significant differences in age at intake and in the lifetime number of hospitalizations. Post hoc comparisons of age at intake indicated that participants who had a history of alcohol use were older at intake than those who had a history of using cocaine or other substances and those who had no history of substance use. Post hoc comparisons also indicated that participants with a history of cocaine use had been hospitalized more often than those who had not used cocaine but had used other substances. No significant differences in age at first hospitalization or in education were found.

A comparison of participants who had lifetime substance use and those who did not revealed significant differences in current (previous 30 days) substance use. Past substance users were more likely to be currently using substances (χ2=5.2, df=2, p<.05); 132 (75 percent) of the past substance users reported no substance use in the previous 30 days.

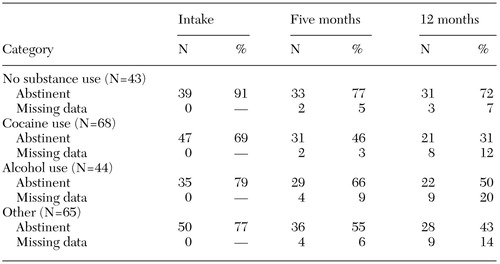

At five months, data were available for 163 (92 percent) of the 177 participants who had lifetime substance use. Of these participants, 112 (69 percent) reported no substance use in the previous 30 days. At 12 months, data were available for 135 (78 percent) of the original 177 participants who had a history of significant substance use. Of these, 89 (66 percent) reported no substance use in the previous 30 days. The overall rate of sustained abstinence at 12-month follow-up, which counted only participants with a history of substance use who had maintained abstinence over the three observation points, was 40 percent when missing participants were assumed to be no longer abstinent and 66 percent when missing participants were excluded.

Abstinence rates in the 30 days before intake did not differ significantly by category of substance use. Forty-seven participants (69 percent) in the cocaine group, 50 participants (77 percent) who had used substances other than cocaine and alcohol, and 35 (80 percent) in the alcohol group were abstinent during the 30 days before intake.

At five months, abstinence rates for the previous 30 days differed significantly by group (χ2=11.67, df=2, p<.003). Thirty-seven participants (58 percent) in the cocaine group remained abstinent, as did 40 (67 percent) who had used substances other than cocaine and alcohol and 35 (90 percent) in the alcohol group. At 12 months, abstinence rates for the previous 30 days remained significantly different by group (χ2=7.14, df=2, p<.03). Twenty-eight participants (53 percent) in the cocaine group were abstinent, as were 35 participants (71 percent) who had used substances other than cocaine and alcohol and 26 (79 percent) in the alcohol group.

A survival analysis over the 12-month follow-up period showed group differences in abstinence rates; overall abstinence rates were lower for all groups because of the analytic approach. At five months, the groups differed significantly in rates of abstinence (χ2=11.67, df=2, p<.01); at 12 months, group differences remained (χ2=7.14, df=2, p<.05): 28 (52 percent) of 53 participants in the cocaine group were still abstinent, compared with 35 (71 percent) of 49 participants who had used other substances and 26 (79 percent) of 33 in the alcohol group. When we assumed that participants with missing data were no longer abstinent and included them in our computations, survival analysis showed a similar trend, although no significant difference between the groups was found. The cocaine group continued to show the poorest 12-month abstinence rate (31 percent), as shown in Table 2.

A multivariate analysis of variance comparing participants' PANSS factor scores at intake revealed significant differences in symptoms between substance use groups (F=2.61, df=3, 219, p<.001). Individual analyses of variance indicated significant differences in the negative component (F=3.11, df=3, 219, p<.05), the cognitive disorganization component (F=4.83, df=3, 219, p<.05), and the hostility component (F=2.87, df=3, 219, p<.05).

Post hoc comparisons indicated that participants without a history of substance use or with a history of alcohol use only had more severe negative and cognitive disorganization symptoms than participants with a history of lifetime cocaine use or participants who had used substances other than alcohol or cocaine. Furthermore, post hoc comparisons indicated that participants who had used cocaine or who had used alcohol only had more severe hostility symptoms than those who had no history of substance use or those who had used substances other than cocaine and alcohol.

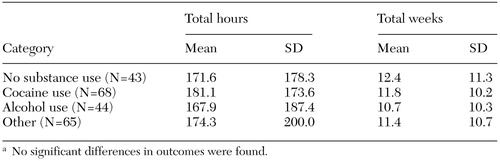

Table 3 summarizes participants' work outcomes at six months. No significant differences were found in the number of hours of work or the number of weeks of participation in the program between participants who had lifetime substance use and those who did not. When those with lifetime substance use were further categorized by type of substance, no significant differences were found in the number of hours or weeks of work.

No association was found between current substance use and the number of hours worked and the number of weeks of participation in the work program. Participants who used substances during the program and those who were abstinent did not differ significantly in the number of hours worked or the number of weeks of participation.

Discussion and conclusions

The proportion of participants with past or current substance use was substantially larger in our study than in other studies based on community samples. However, the substance use rates in our sample were consistent with those in other Veterans Affairs studies of patients with dual diagnoses (27) and may reflect a demographic composition related to past military affiliation. Our rates may also be somewhat higher than those reported in the literature because we used ASI criteria for substance use rather than the more conservative DSM criteria for abuse.

Even though a large proportion of participants had a history of substance use, our results indicate that a majority of them had become abstinent before they entered the study. Assessments for the 30 days before intake, for the 30 days before the five-month follow-up, and for the 30 days before the 12-month follow-up showed that two-thirds to three-quarters of our sample were abstinent during those periods.

On the basis of a survival analysis, the rate of sustained abstinence over 12 months was 66 percent, which is slightly lower than the 75 percent reported by Dixon and colleagues (2). When we assumed that patients who were lost to follow-up had resumed using substances, the rate dropped to 40 percent, which is also slightly lower than the 50 percent that Dixon and colleagues reported when they made the same conservative adjustment. They concluded—and we concur—that these rates were "still impressive given the unfortunate vulnerability of these individuals to substance abuse."

Participants who used substances during the 30 days before they entered the program were more likely than those who were abstinent at entry to report use in the 30 days before the 12-month assessment. This finding also matches that of Dixon and colleagues (2), who reported that their patients with current substance abuse at baseline were more likely to have a recurrence of substance abuse during the one-year follow-up period. We also found that the participants in our study who had a history of cocaine use were more likely than users of other types of substances to experience relapse, even when they were abstinent before entry. This finding suggests that people with schizophrenia who use cocaine face the greatest challenge in maintaining abstinence.

Our results also support the hypothesis that specific types of drug use are differentially related to symptom profiles. Participants with a history of cocaine use were more likely to have high scores on the PANSS hostility component and less likely to have negative symptoms, which makes sense intuitively, given that use of stimulants may lead to irritability and lability (28). It may seem counterintuitive that participants with lifetime alcohol use and those with no history of substance use were more likely to be cognitively disorganized than those in the other groups.

However, the background characteristics of the participants in our study may provide an explanation. Participants with a history of alcohol use were more likely to be older, possibly indicating a longer period of active substance use. Longer duration of illness, combined with prolonged substance use, may be related to cognitive decline. For the nonusers, it is possible that more severe symptoms of cognitive disorganization make it difficult to consistently obtain substances of abuse, and for that reason they did not meet our substance use criteria. These distinct symptom patterns support the validity of our substance use categories. The patterns suggest that there may be important clinical differences among patients who have both substance use problems and mental illness, depending on what substances they use.

Our results have several clinically relevant implications. First, the finding that most participants who were abstinent at intake were still abstinent during the 30 days before the five-month and 12-month assessments suggests that people with schizophrenia and substance use can maintain their recovery over extended periods. Second, active substance use did not directly affect the number of weeks of participation or the number of hours of work in the rehabilitation program. Even cocaine users who appeared to be most vulnerable to relapse were just as likely to participate in rehabilitation as those who remained abstinent.

This finding suggests that substance use and work are semiautonomous. Like other people who work and also use substances, persons with schizophrenia may alter their use pattern to minimize the immediate impact of substance use on work function. Thus we found no evidence that substance use negatively affected work participation or that working increased abstinence rates.

This study did not directly test the value of behavioral contingencies for relapse or of making abstinence a prerequisite to work rehabilitation. However, we infer from our results that such strategies may be contraindicated for this population, because substance use does not necessarily cause immediate vocational dysfunction. It is possible that the advantage of continuing to engage people who have schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder through work rehabilitation outweighs the potential benefit of insisting on abstinence before entry and making work participation contingent on continued abstinence. Although these strategies may have merit in a population with a primary diagnosis of substance dependence, additional research is needed to determine their effectiveness for people with severe mental illness.

Our study had several important limitations. First, our sample consisted primarily of self-selected male veterans and may not have been representative of the full range of patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Second, attrition rates at the five-month and one-year assessments—10 percent and 22 percent, respectively—were higher than we had hoped, although better than the 34 percent attrition reported by Dixon and colleagues (2). We have followed their example by presenting the results of a survival analysis that took the resulting missing data into account. Also, we used ASI criteria for substance use, which are less stringent than DSM substance abuse criteria and may have inflated lifetime substance use rates in our sample. Finally, history of substance use was based on self-reports and therefore may have been biased.

Our study used methods similar to those of Dixon and colleagues (2) and yielded findings similar to theirs. Despite the limitations we have noted, this replication of results should give clinicians and families reason to be hopeful that most persons with schizophrenia who abuse substances may eventually achieve sustained abstinence. Our recommendation that substance users who have schizophrenia be included in work rehabilitation programs is consonant with recent comments by Drake and Wallach (29) that policies for persons with dual diagnoses should "create safe and protective environments along with the development of opportunities for educational, social, and vocational success."

Although our results did not show that work rehabilitation improved abstinence, persons with a history of substance use were just as successful as the other participants. By staying engaged in work activity, they enjoyed the benefits of less severe symptoms, higher income, and a better quality of life that our paid work program produced (14,15,16). Over a longer period such psychological and psychosocial improvements might also increase the chances of sustained abstinence in this population.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the Rehabilitation Research and Development Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

The authors are affiliated with the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System in West Haven and Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven. Send correspondence to Dr. Bell at Psychology Service 116B, VA Connecticut Healthcare System, 950 Campbell Avenue, West Haven, Connecticut 06516 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Characteristics of persons with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who participated in a work rehabilitation program

|

Table 2. Results of survival analysis showing sustained abstinence over 12 months for participants in a work rehabilitation program, by lifetime substance use category

|

Table 3. Work outcomes at six months among participants in a work rehabilitation program, by lifetime substance use categorya

a No significant differences in outcomes were found

1. Lehman AF, Myers CP, Corty E: Assessment and classification of patients with psychiatric and substance abuse syndromes. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:1019-1025, 1989 (reprinted in Psychiatric Services 51:1119-1125, 2000)Google Scholar

2. Dixon L, McNary S, Lehman AF: Remission of substance use disorder among psychiatric inpatients with mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:239-243, 1998Abstract, Google Scholar

3. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE: An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 168:224-230, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Mueser KT, Yarnold PR, Levinson DF, et al: Prevalence of substance abuse in schizophrenia: demographic and clinical correlates. Schizophrenia Bulletin 16:31-56, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Alterman AI, Erdlen FR, Murphy E: Alcohol abuse in the psychiatric hospital population. Addictive Behavior 6:69-73, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Drake RE, Osher FC, Noordsy DL, et al: Diagnosis of alcohol use disorders in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 16:57-67, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Cohen M, Klein D: Drug abuse in a young psychiatric population. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 40:448-455, 1970Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Barbee JG, Clark PD, Crapanzano MS, et al: Alcohol and substance abuse among schizophrenic patients presenting to an emergency psychiatric service. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 177:400-407, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Mueser KT, Yarnold PR, Bellak AS: Diagnostic and demographic correlates of substance abuse in schizophrenia and major affective disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 85:48-55, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Khantzian EJ: The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. American Journal of Psychiatry 142:1259-1264, 1985Link, Google Scholar

11. Lysaker PH, Bell MD, Milstein RM, et al: Relationship of positive and negative symptoms to cocaine abuse in schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 182:109-112, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Fowler IL, Carr VJ, Carter NT, et al: Patterns of current and lifetime substance use in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:443-455, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Mueser K, Drake R, Wallach M: Dual diagnosis: a review of etiological theories. Addictive Behaviors 23:717-734, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Bell MD, Lysaker PH, Milstein RM: Clinical benefits of paid work activity in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 22:51-67, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Bell MD, Lysaker PH, Milstein R: Clinical benefits of paid work activity in schizophrenia:1-year follow-up. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:317-325, 1997Google Scholar

16. Bryson GJ, Bell MD: Quality of life benefits of paid work activity in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 36:323, 1999Google Scholar

17. Bartels SJ, Drake RE, Wallach MA: Long-term course of substance use disorders among patients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 46:248-251, 1995Link, Google Scholar

18. Drake RE, Mueser KT, Clark RE, et al: The course, treatment, and outcome of substance disorder in persons with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:42-51, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Drake RE, Wallach MA: Substance abuse among the chronic mentally ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:1041-1945, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

20. Mueser K, Bellack AS, Blanchard JJ: Comorbidity of schizophrenia and substance abuse: implications for treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 60:845-856, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Brunette MF, Mueser KT, χie H, et al: Relationships between symptoms of schizophrenia and substance abuse. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 185:13-20, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Shaner A, Roberts LJ, Eckman TA, et al: Monetary reinforcement of abstinence from cocaine among mentally ill patients with cocaine dependence. Psychiatric Services 48:807-810, 1997Link, Google Scholar

23. Spitzer R, Williams G, Gibbon M: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R. New York, New York Psychiatric Institute, 1989Google Scholar

24. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler L: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 13:261-276, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

25. Bell MD, Lysaker PH, Milstein RM, et al: Five-component model of schizophrenia: assessing the factorial invariance of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale. Psychiatry Research 52:295-303, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Bell MD, Milstein R, Beam-Goulet J, et al: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale: reliability, comparability, and predictive validity. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:723-728, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Kovasznay B, Fleisher J, Tanenberg-Karant M, et al: Substance use disorder and the early course of illness in schizophrenia and affective psychosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:195-201, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Seibyl JP, Satel SL, Anthony D, et al: Effects of cocaine on hospital course in schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 181:31-37, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Drake R, Wallach MA: Dual diagnosis:15 years of progress. Psychiatric Services 51:1126-1129, 2000Google Scholar