Gender Differences in Juvenile Arrestees' Drug Use, Self-Reported Dependence, and Perceived Need for Treatment

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: The authors examined gender differences in drug use, self-reported dependence, and perceived need for treatment in a national sample of juvenile arrestees and detainees between the ages of nine and 18 years. METHODS: A sample of 4,644 boys and girls, drawn from the Juvenile Drug Use Forecasting Survey from 1992 to 1995, was matched by sex within each of seven sites by survey year. In anonymous interviews, respondents were asked about their living arrangements, drug use, and need for drug treatment. Questions about drug use covered marijuana, cocaine, crack, heroin, crystal methamphetamine, amphetamines, and phencyclidine (PCP). Logistic regression was used to identify significant predictors of drug dependence and perceived need for treatment. RESULTS: Girls were significantly more likely than boys to report dependence but were no more likely to report a need for treatment. Among those who reported current, frequent drug use, girls were significantly less likely than boys to report a need for treatment. Girls who reported having more severe drug problems were more likely than their male counterparts to report dependence and a need for treatment. CONCLUSIONS: The ways in which juvenile arrestees report drug dependence and need for treatment differ by gender. Clinicians should assess and reduce barriers to treatment perceived by girls in particular to engage them in services before their drug use escalates.

The most common psychiatric problem among women in the criminal justice system is drug abuse and dependence (1). Women have more severe drug-related and other mental health problems than men and are more likely to identify their drug use as a problem (2). Studies have found that women who are involved with the criminal justice system are no more likely than their male counterparts to report a need for treatment (3,4). In fact, women with substance use problems are less likely than their male counterparts to participate in treatment (5,6).

It is unknown whether similar gender differences in self-reported dependence and need for treatment exist among juvenile arrestees or detainees. In this study we evaluated gender differences in self-reported drug use, dependence, and perceived need for treatment in a sample of juvenile arrestees. (Throughout this article, "arrestees" will be used to refer to both arrestees and detainees.)

Factors hypothesized to be associated with participation in treatment include predisposing variables, such as gender and need, that influence an individual's inclination to use health services (7,8,9,10). Need for treatment refers to health status, symptoms, or degree of illness and can be assessed professionally—with clinical criteria—or subjectively—by self-appraisal.

More women than men report symptoms, seek help, and use health care services in general (11). In the juvenile justice system, girls and boys differ significantly in the type and degree of their problems. Delinquent girls are more likely than their male counterparts to have experienced severe neglect (12), out-of-home placement (13,14), and sexual or physical abuse (6,15). Given these differences, the degree and type of drug involvement and attitudes toward help-seeking are expected to differ by gender.

Perceived need for treatment is a subjective self-assessment of problem severity (10). It can be measured indirectly by an individual's own admission of dependence on a drug or directly by a self-reported need for professional help. In a study of adult arrestees by Longshore and colleagues (3), self-reported dependence was the strongest predictor of perceived need for treatment, indicating that these two variables are highly correlated.

However, admitting dependence is not the same as expressing a desire for treatment. Some people who acknowledge dependence on drugs may not consider their dependence a problem that is serious enough to warrant professional intervention. Others may be reluctant to admit a need for treatment because of perceived barriers to treatment. For example, a lack of sensitivity to women's particular needs and concerns among treatment providers has been cited as one barrier to women's seeking treatment (16,17).

Unlike perceived need, evaluated need for treatment is measured objectively according to clinical judgment and criteria. Clinical interviews or self-administered instruments are used to assess the severity of an individual's drug problem according to established standards, such as those in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (18). The magnitude of a drug problem is indicated by criteria such as age at first use, frequency of use, polydrug use, and number of years of regular drug use (19). An individual's admission of problematic behaviors according to these indicators alone, even in the absence of self-reported dependence or need for treatment, informs clinicians of the degree of the need for treatment. Both evaluated and perceived need for treatment are influenced by the degree of drug use problems. In a study of adult arrestees by Fiorentine and Anglin (4), the severity of drug use was one of the strongest predictors of perceived need for treatment.

In our study, measures of drug use problems were included as predictors of self-reported dependence and perceived need for treatment. We hypothesized that the severity of drug problems and current use—that is, evaluated need for treatment—would be greater among girls than boys. In terms of perceived need for treatment, we predicted that girls would be more likely than boys to identify their drug use as problematic and therefore would report more dependence. However, we did not expect boys and girls to differ significantly in their self-reported need for treatment. Further, we hypothesized that the severity of the drug problem and frequent current use would interact with gender in predicting self-reported dependence and perceived need for treatment.

Methods

Sample and procedures

The sample was drawn from the National Institute of Justice Drug Use Forecasting Program, which has since been converted to the Arrestee Drug Use Monitoring Program. In selected cities throughout the United States, locally trained nonuniformed staff are contracted by the National Institute of Justice to conduct anonymous interviews and drug screenings among juvenile arrestees within two days of their arrival at a booking facility. Consenting youths are asked questions about their current living arrangements, drug use, and perceived need for drug treatment. Response rates for adult arrestees have been consistently high: more than 90 percent of potential participants consent to be interviewed, and more than 80 percent agree to provide a urine specimen (20).

Data from the survey years 1992 to 1995 were combined across seven program sites that included juvenile females in all four years—Birmingham, Denver, Indianapolis, Phoenix, Portland, San Antonio, and San Jose. The sample of 11,186, which was restricted to participants between the ages of nine and 18 years, comprised 8,864 boys (79.2 percent) and 2,322 girls (20.8 percent). To produce an even sex ratio, respondents were matched by sex within each site by survey year, producing 28 stratified groups. Overall, about 26 percent of the male sample was randomly selected, resulting in a matched group of 2,325 boys, for a total sample of 4,644.

Variables

This study focused on seven drugs for which perceived need for treatment was measured: marijuana; cocaine; crack; heroin, including black tar heroin; crystal methamphetamine; amphetamines; and phencyclidine (PCP). Respondents who answered that they could use treatment for drug use, with or without treatment for alcohol use, were asked to specify the drug for which they could use treatment. Participants were then asked whether they had used each drug during their lifetime, during the previous month, and during the previous 72 hours. They were also asked the age at which they first used each drug and whether they had ever felt dependent on the drug. Self-reported dependence and perceived need for treatment were coded 1 for an affirmative response in relation to any one of the seven drugs and 0 for a negative response.

Drug use problems were measured by five dichotomous indicators: first use before the age of 14; polydrug use, defined as ever having tried three or more drugs; injection drug use, defined as ever having injected a drug; recent drug use, measured by a positive urinalysis for marijuana, cocaine, opiates, amphetamines, or PCP; and highly frequent drug use, defined as use of marijuana six or more times or any of the "hard" drugs three or more times in the previous month.

The five drug use indicators were entered into a principal components factor analysis with a varimax rotation. This procedure yielded a two-factor solution that accounted for 56.8 percent of the variance. The first factor comprised injection drug use, polydrug use, and early age at first use. This factor was used to create a scale called "severity," which had a range of 0 to 3. The items that loaded on the second factor, urinalysis results and frequency of drug use over the previous month, were used to create a second scale, labeled "current use," which ranged from 0 to 2.

Lifetime prevalence of use by gender for each of the seven drugs was estimated on the basis of self-report. Gender differences were examined on a bivariate level for each of the five drug problem indicators, drug problem severity and current use indexes, self-reported dependence, and perceived need for treatment. Logistic regression models were run separately for dependence and perceived need for treatment to examine the effect of gender while controlling for drug problem severity, current use, and key demographic variables.

After evaluating main effects, we included two-way interactions between gender and drug problem severity and between gender and current use to examine how drug-related problems interact with gender to predict self-perceptions of drug dependence and need for treatment. The survey site was included in the logistic regressions for cluster adjustment. We addressed potential clustering of observations within a site by using a robust variance estimator through the STATA statistical software program (21). According to the STATA manual, this procedure is a variant of the procedure outlined by Huber (22) and White (23,24). The use of this procedure limits the generalizability of the results to the study sites.

Results

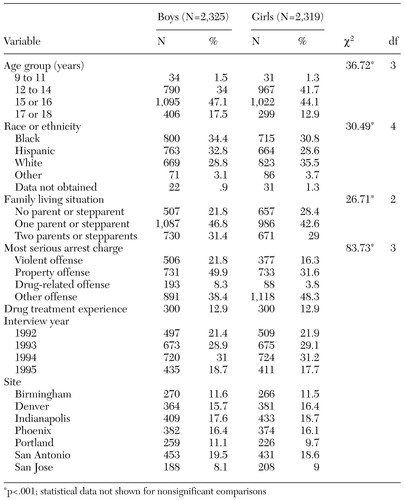

Demographic and other characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 1. The mean±SD age of the boys and girls in the sample was 14.9±1.53 years. Black, white, and Hispanic youths each made up about a third of the overall sample. Older adolescents, blacks, and Hispanics were overrepresented among boys, who were more likely than girls to be arrested for violent, property, and drug-related offenses. Girls were significantly more likely than boys to be arrested for status offenses, such as running away and truancy, and to be living with no parents or stepparents. No significant gender difference in drug treatment experience was found.

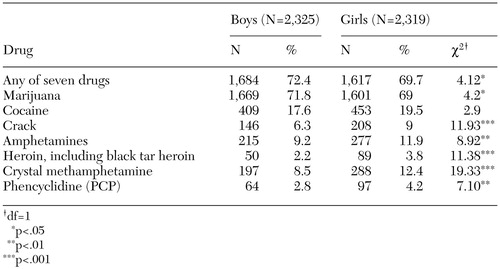

The estimates of lifetime prevalence of drug use by gender are listed in Table 2. For all drugs except cocaine, significant differences between boys and girls were found. Marijuana was the only drug for which the prevalence of use was higher among boys. More girls than boys reported trying crack, heroin, amphetamines, crystal methamphetamine, and PCP.

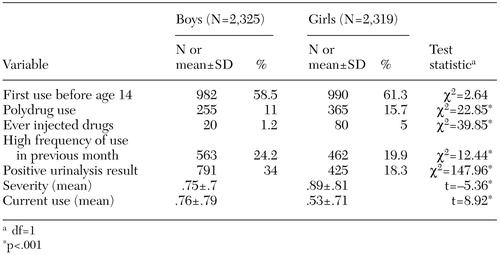

Significant gender differences were found for four of the five drug problem indicators, as can be seen in Table 3. Nearly 16 percent of girls, compared with 11 percent of boys, were classified as polydrug users. One percent of boys and 5 percent of girls reported ever having injected drugs. A high frequency of drug use in the previous month and a positive urinalysis result were significantly more common among boys than girls. About 24 percent of boys and 20 percent of girls were classified as high-frequency drug users. A positive urinalysis result was reported for 34 percent of the boys, compared with 18 percent of the girls. Age at first use did not differ significantly between girls and boys. Girls had a significantly higher mean score on the severity index, and boys had a significantly higher mean score on the current use composite.

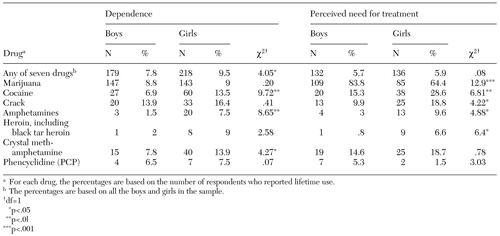

Data on self-reported dependence and perceived need for treatment are presented in Table 4. Nearly 10 percent of the girls and 8 percent of the boys reported that they had ever felt dependent on at least one of the seven drugs. Girls reported significantly higher rates of dependence on cocaine, amphetamines, and crystal methamphetamine. However, girls were no more likely than boys to report a need for treatment for drug abuse overall. About 6 percent of boys and girls stated that they could use treatment for any one of the seven drugs. Of those who reported a need for treatment, more girls than boys reported a need for treatment for use of cocaine, crack, heroin, or amphetamines. However, significantly more boys than girls reported needing treatment for marijuana use.

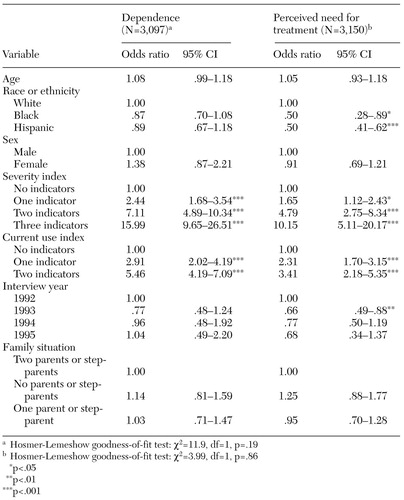

The results of the logistic regression analyses predicting dependence and perceived need for treatment are summarized in Table 5. Gender was not a significant predictor of self-reported dependence or perceived need for treatment. The only significant predictors of dependence were drug problem severity and current use. Compared with respondents who had no severity indicators, those who had one, two, or three indicators were significantly more likely to report dependence on at least one drug. Respondents who had one or two current use indicators were also more likely than those with no current use indicators to report dependence. Perceived need for treatment was predicted by the severity of the drug problem and current use, race or ethnicity, and interview year. Greater severity and higher current use scores were associated with a greater likelihood of a perceived need for treatment.

We further investigated sex differences by entering two interaction terms—sex by severity and sex by current use—into the logistic regression models (data not shown). The sex-by-severity interaction significantly predicted dependence. Girls who had one severity indicator were 1.47 times as likely as boys to report that they were dependent on a drug (95 percent confidence interval=1.02 to 2.12). Among arrestees who had three severity indicators, girls were 3.32 times as likely as boys to admit dependence (CI=3.32 to 8.33).

For perceived need for treatment, the sex-by-severity interaction was significant at the level of only three severity indicators. Among the most severe drug users, girls were 7.1 times as likely as boys to say that they were dependent (CI=2.23 to 22.65). Current use interacted significantly with gender in predicting perceived need for treatment. Among respondents with either one current use indicator (odds ratio=.53; CI=.30 to .92) or two indicators (odds ratio=.40; CI=.24 to .68), girls were significantly less likely to report a need for treatment.

Discussion and conclusions

The female juvenile arrestees in our study were more likely than their male counterparts to endorse indicators of severe or chronic drug use. The boys, on the other hand, were more likely to be engaged in current frequent drug use. Thus our hypothesis that the evaluated need for treatment would be greater among girls than boys was only partially supported. As we expected, the perceived need for treatment was higher among girls than boys, but they were equally likely to state that they could use treatment. Our findings parallel those from studies of adult arrestees, in which a greater proportion of women than men reported dependence but women were no more likely not to report a need for treatment.

For both sexes, the severity of the drug problem was the strongest predictor of self-reported dependence and perceived need for treatment. The severity of the problem also interacted significantly with gender in predicting dependence and perceived need for treatment. In support of our hypothesis, girls were significantly more likely than boys to admit dependence at higher levels of severity and to acknowledge a need for help. By contrast, among those who were actively engaged in current drug use, girls were significantly less likely than boys to report a need for treatment.

These findings may be interpreted in the context of the relative proportions of males and females in the juvenile justice system. The vast majority of juvenile arrestees are boys, which suggests two major differences. First, adolescent girls who are arrested are more deviant relative to their same-sex peers than is the case for males. Research indicates that many delinquent girls are more likely than boys to have experienced trauma, such as physical and sexual abuse (6,15). The risk of drug abuse among persons who have been traumatized is significantly greater than among those who have not (25).

In addition, depression is significantly more common among jailed women than among their male counterparts (26). In the general population, adolescent girls have twice the rate of depression as adolescent boys (27). For many women who use drugs, drug use has been conceptualized as a coping strategy for escaping from stress (28). The girls in our study who currently used drugs frequently were more reluctant than the boys to state that they needed treatment, perhaps because they were more likely to rely on self-medication.

Second, because fewer girls are arrested than boys, it is possible that fewer services are available that are appropriate for girls. The smaller proportion of females in the criminal justice system means that the per capita expense of providing services similar to those provided for men is too high (29). Females in the criminal justice system are confronted with more barriers and have fewer options for drug treatment (16,30). Thus for girls to be willing to consider drug treatment as a potentially helpful resource, their level of drug use may need to be more extreme.

One implication of this finding is that delinquent girls' perceived barriers to treatment should be identified and reduced to increase their willingness to accept treatment, before the severity of their drug use becomes chronic and progresses to the point of injection and polydrug use. We could not determine whether girls who abuse drugs might be more willing to accept treatment that addresses past trauma or current mental health problems than substance abuse treatment per se. Future surveys of high-risk adolescents, such as the Arrestee Drug Use Monitoring Program, would be enhanced by obtaining information about psychiatric symptoms.

Our study used a convenience sample and was limited to juvenile arrestees in seven sites across the United States. Because of adjustment for possible clustering effects of site in the logistic regressions, the results are not generalizable beyond the sites used in these analyses (21), and caution is warranted in applying these findings to other samples. Nevertheless, the limitations of using a convenience sample were balanced by the strengths of the Drug Use Forecasting Program data. Large, multisite surveys of adolescents in the juvenile detention system are rare, and the inclusion of drug testing is costly.

As in many studies that rely on self-report, our study was limited by the possibility of differences in reporting patterns across demographic groups. In a previous study with a similar sample of juvenile arrestees, girls were more willing than boys to validly disclose marijuana use (31). This finding raises the possibility that the prevalence of marijuana use among boys in our study was an underestimate that influenced the results. However, in treatment research the validity of reporting a need for help is not necessarily problematic. A reluctance to report a need for professional help on the part of persons who are clinically evaluated as needing treatment is in itself an important topic of inquiry.

Our study showed how the perception of a need for help differs by gender and by drug problem severity. Service providers who work with high-risk delinquent youths in the juvenile justice system should consider these differences when attempting to engage such individuals in treatment.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant DA-09286 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). The authors thank Vera Lopez, Ph.D., for her helpful contribution to this research.

Dr. Kim is assistant professor of clinical psychology and Dr. Fendrich is associate professor of psychology at the Institute for Juvenile Research (M/C 747), Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago, 840 South Wood, Chicago, Illinois 60612 (e-mail, [email protected]). An earlier version of this paper was presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Criminology held November 16-20, 1999, in Toronto, Canada, and at the annual scientific meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence held June 17-20, 2000, in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 4,644 boys and girls from the Drug Use Forecasting Survey sample between 1992 and 1995, matched by sex and site

|

Table 2. Lifetime drug use in a sample of 4,644 boys and girls from the Drug Use Forecasting Survey sample between 1992 and 1995

|

Table 3. Indicators of drug problems in a sample of 4,644 boys and girls from the Drug Use Forecasting Survey sample between 1992 and 1995

|

Table 4. Self-reported dependence and perceived need for treatment among 2,325 boys and 2,319 girls from the Drug Use Forecasting Survey sample between 1992 and 1995

|

Table 5. Results of logistic regression predicting self-reported dependence and perceived need for treatment among juvenile arrestees, with cluster adjustment for site

1. Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among incarcerated women: I. pretrial jail detainees. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:505-512, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Peters RH, Strozier AL, Murrin MR, et al: Treatment of substance-abusing jail inmates: examination of gender differences. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 14:339-349, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Longshore D, Hsieh S, Anglin MD: Ethnic and gender differences in drug users' perceived need for treatment. International Journal of the Addictions 28:539-558, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Fiorentine R, Anglin MD: Perceiving need for drug treatment: a look at eight hypotheses. International Journal of the Addictions 29:1835-1854, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Anglin MD, Hser Y, Booth MW: Sex differences in addict careers:4. treatment. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 3:253-280, 1987Google Scholar

6. Finkelstein N: Treatment issues for alcohol- and drug-dependent pregnant and parenting women. Health and Social Work 19:7-15, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Andersen R: A Behavioral Model of Families' Use of Health Services. Research series 25. Chicago, Center for Health Administration Studies, University of Chicago, 1968Google Scholar

8. Andersen R, Newman J: Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 51:95-124, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Aday L, Andersen R: Equity of access to medical care: a conceptual and empirical overview. Medical Care 19:4-27, 1981Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Aday LA, Awe WC: Health services utilization models, in Handbook of Health Behavior Research, vol 1, Personal and Social Determinants. Edited by Gochman DS. New York, Plenum, 1997Google Scholar

11. McMullen PA, Gross AE: Sex differences, sex roles, and health-related help-seeking, in New Directions in Helping, vol 2, Help-Seeking. Edited by DePaulo BM, Nadler A, Fisher JD. New York, Academic Press, 1983Google Scholar

12. Chesney-Lind M, Shelden RG: Girls, Delinquency, and Juvenile Justice. Pacific Grove, Calif, Brooks-Cole, 1992Google Scholar

13. Lewis DO, Shanok SS, Pincus JH: A comparison of the neuropsychiatric status of female and male incarcerated delinquents: some evidence of sex and race bias. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 21:190-196, 1982Crossref, Google Scholar

14. McManus M, Alessi N, Grapentine WL, et al: Psychiatric disturbances in serious delinquents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 23:602-615, 1984Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Viale-Val G, Sylvester C: Female delinquency, in Female Adolescent Development. Edited by Sugar M. New York, Brunner-Mazel, 1993Google Scholar

16. Zanowski GL: Responsive programming: meeting the needs of chemically dependent women. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly 4:53-65, 1987Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Stevens J, Arbiter M, Gilder P: Women residents: expanding their role to increase treatment effectiveness in substance abuse programs. International Journal of the Addictions 24:425-434, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

19. Heitoff KA, Wiseman EJ: Reliability of paper-pencil assessment of drug use severity. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 22:109-122, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Drug Use Forecasting: Annual Report on Adult and Juvenile Arrestees. Washington, DC, National Institute of Justice, 1996Google Scholar

21. STATA Corporation: STATA Users' Guide. College Station, Tex, Stata, 1997Google Scholar

22. Huber PJ: The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under non-standard conditions, in Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium in Mathematical Statistics and Probability. Berkeley, Calif, University of California Press, 1967Google Scholar

23. White H: A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica 48:817-830, 1980Crossref, Google Scholar

24. White H: Maximum likelihood estimation of misspecified models. Econometrica 50:1-25, 1982Crossref, Google Scholar

25. Chilcoat HD, Breslau N: Posttraumatic distress disorder and drug disorders: testing causal pathways. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:913-917, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Teplin LA: Psychiatric and substance abuse disorders among male urban jail detainees. American Journal of Public Health 84:290-293, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Offord DR, Boyle MH, Szatmari P, et al: Ontario Child Health Study: II. six-month prevalence of disorder and rates of service utilization. Archives of General Psychiatry 44:832-839, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Nelson-Zlupko L, Kauffman E, Dore MM: Gender differences in drug addiction and treatment: implications for social work intervention with substance-abusing women. Social Work 40:45-54, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

29. Feinman C: Women in the Criminal Justice System, 3rd ed. Westport, Conn, Praeger, 1994Google Scholar

30. Inciardi JA, Lockwood D, Pottieger AE: Women and Crack-Cocaine. New York, Macmillan, 1993Google Scholar

31. Kim JYS, Fendrich M, Wislar JS: The validity of juvenile arrestees' drug use reporting: a gender comparison. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 37:419-432, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar