Patient Satisfaction, Use of Services, and One-Year Outcomes in Publicly Funded Substance Abuse Treatment

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This longitudinal study examined the relationships among patient satisfaction with substance abuse services, service use, and clinical and employment outcomes. METHODS: Interviews were conducted with 502 adults who were beginning outpatient or residential treatment for substance abuse in a managed care plan in Oregon or in fee-for-service plans in Washington State. The participants were reinterviewed after six months and after one year. Measures of satisfaction and use of services were assessed at six months and clinical outcomes at one year with the Addiction Severity Index. Multivariate regression analyses were used to estimate the relationship between satisfaction and service use and the relationships among satisfaction, use, and one-year outcomes when baseline characteristics were held constant. RESULTS: The final sample included 310 individuals (62 percent) who completed interviews at the three time points. Compared with those who were excluded because of missing data, the patients in the final sample were more likely to be white, to be better educated, to be in outpatient treatment, and to live in Oregon and less likely to be homeless. No significant differences were observed in baseline symptoms between the two groups. Satisfaction with access and effectiveness of services predicted service use at six months. Service use, satisfaction with access, and satisfaction with effectiveness were significantly associated with abstinence from substance use at one year. Neither patient satisfaction nor use of services was related to other outcomes, including employment and the presence of psychiatric symptoms. CONCLUSIONS: Although causation cannot be determined, the results of this study suggest that patient satisfaction is related to both use of services and abstinence from substance use. Longitudinal research using more detailed measures of satisfaction is needed to sort out the complex relationship between satisfaction and service use and the direct and indirect influences of these variables on outcomes.

Consumer satisfaction is integral to measurements of the quality of behavioral health services. Purchasers, providers, and consumers have an interest in identifying patients' perspectives on mental health care to improve the delivery of services (1). Patient surveys can provide information about both the process and the outcomes of care (2). As a process measure, patient satisfaction can yield valuable insights into service delivery. The utility of patient satisfaction as an outcomes measure depends in part on its ability to identify clinically meaningful changes over time (3).

Previous research has often shown a positive association of consumer satisfaction with services and outcomes (4,5,6,7). For example, research conducted among psychiatric inpatients at a veterans hospital found that satisfaction with the effectiveness of services, with staff and clinicians, and with the treatment environment was correlated with improvements in quality of life, symptoms, and level of functioning (8,9).

In another study conducted at a veterans hospital, Druss and colleagues (2) found that patients who were more satisfied with the therapeutic alliance had higher rates of—and more prompt—follow-up care. Patients who were more satisfied were also less likely to be readmitted to the hospital and had shorter stays when they were readmitted. These authors hypothesized that consumers who were more satisfied had better outcomes and thus were less likely to be readmitted.

However, not all performance data yield the same results. One of the few studies that have examined the relationship between satisfaction and outcomes in substance abuse treatment did not find any correlation between satisfaction and six-month outcomes (10).

Most of this research indicates that satisfaction measures are correlated with clinically meaningful outcomes. However, because the research used cross-sectional designs, there is little evidence that satisfaction data can provide information about clinically meaningful changes over time.

Furthermore, to delineate the relationship between consumer satisfaction and outcomes, it is necessary to identify intervening processes that may influence both variables. For example, an abundance of literature suggests that consumer satisfaction is linked to greater use of services (2,11,12,13,14) and that greater use of services in turn positively influences outcomes, especially in substance abuse treatment (10,15,16,17,18). Thus research that seeks to explicate the relationship between reported satisfaction and outcomes should consider use of services as an intervening factor.

Despite the emphasis on consumer perspectives in performance assessment, few studies have examined the relationships among satisfaction, service use, and prospectively measured clinical outcomes in substance abuse treatment. This prospective study examined the relationships among three different dimensions of consumer satisfaction, service utilization, and one-year outcomes to address two questions. First, do consumers of substance abuse treatment who report greater satisfaction also receive more treatment? Second, does satisfaction with treatment predict outcomes, including abstinence, psychiatric symptoms, and employment?

Methods

Sample

The participants in the study were 502 adults who were receiving public assistance and who were beginning a new residential or outpatient treatment episode. The original study protocol was designed to compare substance abuse treatment in a managed care plan and fee-for-service plans. About half of the participants (220 individuals, or 44 percent) were enrolled in the Oregon Health Plan and were receiving services at one of 30 facilities in Oregon under contract with a nonprofit managed care organization. The rest of the participants were receiving services at one of 25 facilities located in counties in neighboring Washington State that were selected for their demographic similarity to the counties served by the managed care organization in Oregon; however, the facilities were state-administered, non-managed care programs.

Participants were recruited by treatment providers at the facilities in both states; the providers obtained the patients' informed consent. Patients were recruited over a nine-month period beginning in the fall of 1997.

Of the 502 patients who were interviewed at baseline, 359 (72 percent) were interviewed at six months and 369 (74 percent) were interviewed at 12 months. A total of 331 patients (66 percent) participated in all three interviews. Chart reviews were conducted at six months for 473 patients (94 percent) to determine service use. The final sample consisted of 310 individuals for whom all three interviews and chart reviews were available. Compared with the rest of the sample, these patients were more likely to be white, to be better educated, to be in outpatient treatment, and to live in Oregon and less likely to be homeless. No significant differences were observed in baseline health status, mental health status, or symptoms between the two groups.

Measures

Satisfaction measures. The three items used to measure satisfaction tap into three distinct dimensions that are commonly considered to be important domains of consumer satisfaction (19). The first item identifies satisfaction with access to services: "It was easy for me to get the substance abuse services I thought I needed." The second identifies satisfaction with the effectiveness of treatment: "The substance abuse services I received were helpful to me." The third item identifies global satisfaction with care: "Overall, I am satisfied with the substance abuse services I received over the past six months." All three items used a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1, "strongly agree," to 5, "strongly disagree." Because responses to the satisfaction items were skewed toward the positive end of the scale, responses to all three items were divided into three categories for the multivariate analyses. A score of 5 indicated high satisfaction (5); 4, medium satisfaction (4); and 1, 2, or 3, low satisfaction.

Outcome measures. Outcomes included the frequency and type of substance use, the number and type of psychiatric symptoms, and employment status. Clinical outcomes were measured with the Addiction Severity Index, which was administered at baseline and at the one-year follow-up (20). Because a large proportion of respondents reported at one year that they were abstinent from alcohol and other drugs (156 patients, or 50 percent), a dichotomous variable was created to indicate whether an individual had abstained from all forms of substance use in the 30 days before the interview. Similarly, because a large proportion of respondents indicated that they had no psychiatric symptoms at the one-year follow-up (142 patients, or 46 percent), responses were dichotomized to indicate the presence or absence of symptoms within the previous 30 days. Finally, employment status was measured with a dichotomous variable that indicated whether the participant had been employed in the 30 days before the one-year follow-up interview.

Measures of service use. A chart review was conducted six months after each patient's admission to the index treatment episode to determine service use. A total of 245 patients (79 percent) had completed their treatment before the six-month follow-up. The hours during which patients received individual, group, or family therapy during the first six months of treatment were summed to create a variable that indicated the total number of hours of treatment received. In addition to formal treatment, self-reported frequency of participation in self-help groups—for example, Alcoholics Anonymous—was ascertained at baseline and at six months.

Analyses

A three-stage analysis was conducted to identify the relationships among satisfaction, service use, and outcomes. First, bivariate correlations were assessed for all three satisfaction items, hours of therapy, and outcome measures. Because many of the variables are measured at the ordinal level, Spearman's rho correlation coefficients were estimated. In addition, because all three satisfaction items, number of hours of therapy, participation in self-help groups, and abstinence from substance use, were correlated, each variable was retained in the multivariate analyses.

In the second stage of the analysis, multivariate ordinary least-squares regression was used to estimate the relationship between satisfaction and duration of therapy when demographic variables, baseline health status, psychiatric symptoms, and abstinence were held constant. In the third stage, multivariate logistic regression was performed to assess the relative impact of the duration of treatment, participation in self-help groups, and satisfaction on abstinence from substance use when demographic characteristics, baseline health status, psychiatric symptoms, and abstinence were held constant.

Because the study sample was composed of consumers from two different populations—a managed care population in Oregon and a non-managed care population in Washington State—state of residence was included as a variable in all regression models to control for unmeasured variation between the two groups. In addition, interaction effects for state and amount of treatment as well as each of the satisfaction measures on outcomes were estimated. None of these effects were significant.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

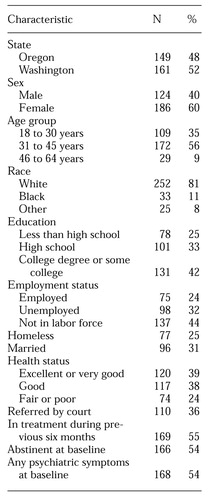

Table 1 shows the demographic, health status, and substance abuse characteristics of the final sample of 310 at admission. Most of the patients were female, were between 31 and 45 years of age, and were white. Most participants had at least a high school education. However, only one-quarter of the participants were employed at admission, and a similar proportion were homeless. More than one-third of the participants had been referred to treatment by a court, and more than half had been in treatment during the six months before their admission. Just over half reported having abstained from all substance use in the 30 days before their admission.

The relatively high rate of abstinence at baseline can be partly explained by the large proportion of respondents who had recently received treatment or had been incarcerated in the six months before admission. Of the 166 participants who abstained from substance use at baseline, 63 (38 percent) had recently been discharged from residential treatment, 78 (47 percent) had attended self-help groups at least weekly, and 20 (12 percent) had been incarcerated before admission.

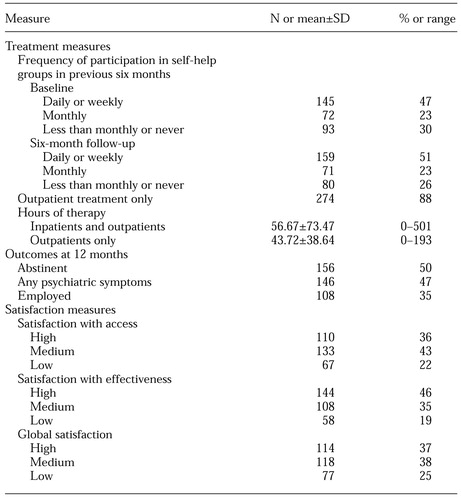

Table 2 shows participants' responses to items measuring the treatment, satisfaction, and outcome measures. Nearly half of the sample participated in self-help groups at least weekly in the six months before admission, and just over half participated in these groups at least weekly during the six months after admission. Most of the participants were receiving outpatient treatment services. Half of the participants reported having abstained from any substance use in the 30 days before the one-year follow-up, just under half reported that they had had psychiatric symptoms during the same period, and just over one-third reported being employed. As is routinely found in satisfaction surveys, a large proportion of the sample reported high satisfaction—36 percent reported high satisfaction with access, 46 percent reported high satisfaction with effectiveness, and 37 percent reported high global satisfaction.

Bivariate analyses

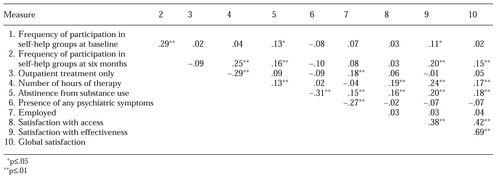

Table 3 lists the Spearman correlation coefficients for treatment, satisfaction, and outcome measures. Several low-to-moderate correlations were observed among measures of service use, satisfaction, and abstinence from substance use. The frequency of participation in self-help groups at baseline was significantly positively associated with the frequency of participation at six months, with abstinence from substance use, and with satisfaction with the effectiveness of services. The frequency of participation in self-help groups at six months was significantly positively associated with the number of hours of therapy, with abstinence from substance use, with satisfaction with effectiveness, and with global satisfaction. The number of hours of therapy was significantly positively associated with abstinence and with all three satisfaction items. Abstinence from substance use was also positively associated with all three satisfaction items and negatively associated with the presence of any psychiatric symptoms at one year. Neither employment nor the presence of psychiatric symptoms was associated with the duration of therapy or with satisfaction.

Satisfaction and amount of treatment

Because significant positive correlations between hours of treatment, frequency of participation in self-help groups, and satisfaction were observed, the relationship between satisfaction and duration of therapy was assessed with ordinary least-squares regression. Three models were estimated to identify the relationship between each of the satisfaction items and duration of therapy.

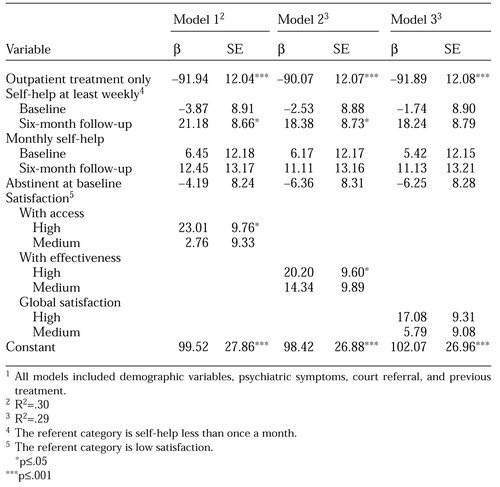

In all three models presented in Table 4, at six months outpatients had, on average, about 90 fewer hours of therapy than patients in residential treatment. Among all patients, those who reported weekly participation in self-help groups at six months had between 18 more hours of therapy (models 2 and 3) and 21 more hours of therapy (model 1) than those who reported monthly participation in self-help groups, which was the referent category.

Two measures of satisfaction—satisfaction with access to services and satisfaction with the effectiveness of services—were significantly associated with the number of hours of therapy. Patients who reported high levels of satisfaction with access had, on average, 23 more hours of therapy than those who reported low levels of satisfaction (model 1). Patients who reported high levels of satisfaction with effectiveness had an average of 20 more hours of therapy than those who reported low levels (model 2). Patients who reported high levels of global satisfaction reported, on average, 17 more hours of therapy than patients who reported low levels, but this association was not significant (p=.07).

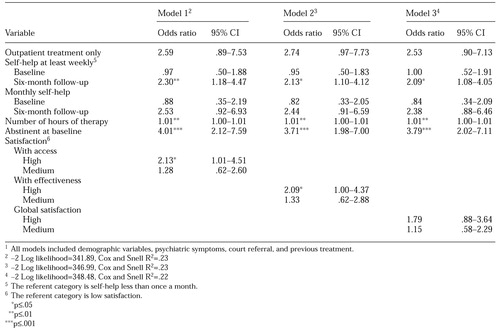

Satisfaction, amount of treatment, and outcomes

Table 5 shows the adjusted odds ratios and 95 percent confidence intervals for predicting abstinence from substance use at one year with the three models. In all three models, weekly participation in self-help groups, the number of hours of therapy, and abstinence at baseline from substance use were significant predictors of abstinence at one year. Patients who participated in self-help groups at least weekly were more likely to have abstained from substance use than those who participated less than once a month (the referent category). Patients who were abstinent from substance use at baseline were much more likely to be abstinent at one year.

The number of hours of therapy also predicted abstinence from substance use at one year. The small odds ratios (1.01) for all three models should be interpreted in the context of the metric of the independent variable. In this case, each additional hour of therapy was associated with a 1 percent increase in the likelihood of abstinence. Two satisfaction items were significantly related to abstinence at one year. Individuals who reported high levels of satisfaction with access and with effectiveness were more than twice as likely to be abstinent from substance use as those who reported low levels.

Discussion and conclusions

This is the first study to examine the relationships among satisfaction with services, service use, and one-year outcomes in publicly funded substance abuse treatment. Two of the three satisfaction items—satisfaction with access and satisfaction with effectiveness—were positively associated with use of services and with abstinence from substance use at one-year follow-up after demographic characteristics and baseline abstinence were controlled for. Neither patient satisfaction nor use of services was associated with other outcomes, including employment and presence of psychiatric symptoms.

This study had several limitations. First, although the baseline and final samples did not differ significantly in symptoms at baseline, only 62 percent of the original sample was retained in the final analyses. Thus it is possible that patients who dropped out of the study were less satisfied than those for whom data were collected at all three points (21). In addition, the sample was not randomly selected, and it included a higher proportion of women and white persons than is commonly found in studies of substance abuse treatment. Thus generalizations about the findings should be made with caution. However, the study does complement studies in which the participants were primarily men (2,9,11).

Another methodologic shortcoming was the use of relatively blunt measures of satisfaction. The study used three satisfaction items, each with 5-point response ranges. Current research on satisfaction measurement suggests that multiple indicators of satisfaction should be used for each relevant domain and that broader response patterns—11-point rather than 5-point scales—should be used to capture more subtle differences in satisfaction (13,19). In addition, although the dichotomous outcome measures yield a straightforward interpretation of the findings, they do not capture other meaningful indicators of the success of treatment, such as reductions in substance use and in problems associated with substance use.

Despite these shortcomings, the results of this study suggest that patients who are more satisfied receive more therapy and are more likely to be abstinent from the use of alcohol or other drugs one year after starting treatment. Although outcomes were measured prospectively, causal inferences about the direct influence of satisfaction on outcomes or the indirect influence on outcomes through greater use of services should be made only with caution.

Because satisfaction and service use were measured concurrently, it is difficult to infer a causal relationship between satisfaction and the amount of treatment. Previous research on satisfaction and use of services has revealed a complex reciprocal relationship that varies in different situations and for different subgroups (22). The evidence from cross-sectional studies, suggesting that consumers who are more satisfied receive more treatment, could be interpreted as reflecting a causal relationship in either direction. Consumers who are satisfied may be more likely to continue to participate in treatment. Conversely, patients who have received more treatment—and presumably have realized relatively more improvement—may be more satisfied. It is also possible that the correlation between satisfaction and service use reflects individual characteristics that we did not measure, such as motivation.

Similar interpretations apply to the relationship between satisfaction and outcomes. Satisfaction with treatment may result in behavioral patterns, such as adherence to treatment, that have an impact on eventual outcomes (1,23). On the other hand, reported satisfaction may simply be an expression of alleviation of symptoms that occurs as a result of treatment. Another possible explanation for the relationship between satisfaction and outcomes is that the patients were matched with appropriate treatments. Patients who are receiving more appropriate individualized treatment may be more likely to report satisfaction and to achieve better functioning after treatment (24,25,26).

This research has implications for both performance measurement and treatment effectiveness. First, even if there is no causal relationship between consumer satisfaction and eventual outcomes, satisfaction is an important outcome indicator to the extent that it can reflect clinically meaningful changes over time. In the absence of clinical outcomes data—or as a complement to such data—consumers' perspectives on the effectiveness of treatment appear to provide useful information about quality. Second, if satisfaction with treatment is causally related to alleviation of symptoms over time—either through greater use of services or through associated behavioral change—then clinical processes should reflect consumers' priorities.

As performance measures, consumer evaluations of care are useful for measuring the process and outcomes of care. Additional research that more fully explicates the relationships between satisfaction and specific dimensions of services and use of services is needed. In addition, longitudinal research is needed to delineate the impact of individual characteristics, such as expectations and motivation, and intervening variables, such as service use, on the relationship between satisfaction and outcomes. Finally, because of the important role of satisfaction in quality improvement, more research is needed to identify individual and service characteristics that predict satisfaction with substance abuse treatment.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported with cooperative agreement UR7 TI 11294 01 from the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. The authors thank Bentson McFarland, M.D., Ph.D., and Irvine Smith, M.S.W.

Dr. Carlson is research associate at CareOregon and clinical assistant professor of public health and preventive medicine at Oregon Health Sciences University in Portland. Dr. Gabriel is senior research associate at RMC Corporation, 522 S.W. Fifth Avenue, Suite 1407, Portland, Oregon 97204 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 310 participants in a study of publicly funded substance abuse treatment

|

Table 2. Responses to items on treatment, satisfaction, and outcomes among 310 participants in publicly funded substance abuse treatment

|

Table 3. Correlation matrix for responses to items on treatment, satisfaction, and outcomes among 310 participants receiving publicly funded substance abuse treatment

|

Table 4. Unstandardized coefficients from ordinary least-squares regression models predicting hours of therapy received by six-month follow-up1

1 All models included demographic variables, psychiatric symptoms, court referral, and previous treatment

|

Table 5. Adjusted odds ratios and 95 percent confidence intervals for abstinence from substance use at one-year follow-up1

1 All models included demographic variables, psychiatric symptoms, court referral, and previous treatment

1. Campbell J: Consumerism, outcomes, and satisfaction: a review of the literature, in Mental Health, United States, 1998. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Henderson MJ. Washington, DC, Center for Mental Health Services, 1998Google Scholar

2. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Stolar M: Patient satisfaction and administrative measures as indicators of the quality of mental health care. Psychiatric Services 50:1053-1058, 1999Link, Google Scholar

3. Smith RG, Manderscheid RW, Flynn LM, et al: Principles for assessment of patient outcomes in mental health care. Psychiatric Services 48:1033-1036, 1997Link, Google Scholar

4. Hansson L, Berglund M: Factors influencing treatment outcome and patient satisfaction in a short term psychiatric ward. European Archives of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences 236:269-275, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Lebow J: Consumer satisfaction with mental health treatment. Psychological Bulletin 91:244-259, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Pekarik G, Wolff CB: Relationship of satisfaction to symptom change, follow-up adjustment, and clinical significance. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 27:202-203, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Ries RK, Jaffe C, Comtois KA, et al: Treatment satisfaction compared with outcome in severe dual disorders. Community Mental Health Journal 35:213-221, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Holcomb WR, Parker JC, Leong, GB, et al: Customer satisfaction and self-reported treatment outcomes among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatric Services 49:929-934, 1998Link, Google Scholar

9. Holcomb WR, Parker JC, Leong GB: Outcomes of inpatients treated on a VA psychiatric unit and a substance abuse treatment unit. Psychiatric Services 48:699-704, 1997Link, Google Scholar

10. McLellan AT, Hunkeler E: Patient satisfaction and outcomes in alcohol and drug abuse treatment. Psychiatric Services 49:573-575, 1998Link, Google Scholar

11. Rosenheck R, Wilson NJ, Meterko M: Influence of patient and hospital factors on consumer satisfaction with inpatient mental health treatment. Psychiatric Services 48:1553-1561, 1997Link, Google Scholar

12. Thomas JW, Penchansky R: Relating satisfaction with access to utilization of services. Medical Care 22:553-568, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Ware JE, Davies AR: Behavioral consequences of consumer dissatisfaction with medical care. Evaluation and Program Planning 6:291-297, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Zastowny TR, Roghmann KJ, Cafferata GL: Patient satisfaction and the use of health services: explorations in causality. Medical Care 27:705-723, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. McLellan AT, Woody GE, Metzger D, et al: Evaluating the effectiveness of addiction treatments: reasonable expectations, appropriate comparisons. Milbank Quarterly 74:51-85, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Moos RH, Finney JW, Ouimette PC, et al: A comparative evaluation of substance abuse treatment: I. treatment orientation, amount of care, and 1-year outcomes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 23:529-536, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

17. Ouimette PC, Moos RH, Finney JW: Influence of outpatient treatment and 12-step group involvement on one-year substance abuse treatment outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 59:513-522, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Westerberg VS: What predicts success? in Treating Addictive Behaviors, 2nd ed. Edited by Miller WR, Heather N. New York, Plenum, 1998Google Scholar

19. Eisen SV, Shaul JA, Clarridge B, et al: Development of a consumer survey for behavioral health services. Psychiatric Services 50:793-798, 1999Link, Google Scholar

20. McLellan AT, Cacciola J, Kushner H, et al: The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index: cautions, additions, and normative data. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 9:192-199, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Cleary PD, McNeil BJ: Patient satisfaction as an indicator of quality care. Inquiry 25:25-36, 1988Medline, Google Scholar

22. Pascoe GC: Patient satisfaction in primary health care: a literature review and analysis. Evaluation and Program Planning 6:185-210, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Westermeyer J: Nontreatment factors affecting treatment outcome in substance abuse. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 15:13-29, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Hser Y, Anglin MD, Fletcher B: Comparative treatment effectiveness: effects of program modality and client drug dependence history on drug use reduction. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 15:513-523, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. McLellan AT, Grissom GR, Zants D, et al: Problem-service "matching" in addiction treatment: a prospective study in 4 programs. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:730-735, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Miller WR: The effectiveness of substance abuse treatment: reasons for optimism. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 9:93-102, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar