Training, Communication, and Information Needs of Mental Health Counselors in the United Kingdom

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This national cross-sectional survey investigated the communication and information needs of mental health counselors in the United Kingdom as well as the difficulty these professionals experienced in obtaining help from other mental health care providers. METHODS: Mailed questionnaires were sent to a random sample of 400 registered counselors. A total of 230 counselors returned the questionnaire, for a response rate of 58 percent. Descriptive statistics, correlations, and multiple logistic regression analysis were used to analyze the results. RESULTS: The respondents reported being in contact mostly with other counselors, general practitioners, and psychiatrists. Most of the respondents (80 percent) reported other counselors to be quite or extremely helpful when consulted; the proportions were much lower for other types of practitioners, especially general practitioners and psychiatrists. Reported barriers to coordination of counseling services included lack of time and communication problems with other professionals. A total of 160 respondents (70 percent) reported not having the necessary training or skills for managing severe cases of mental illness, and 168 (73 percent) indicated that they had a need for information about mental illness. Predictors of information needs were a lack of the necessary skills for managing severe cases, contact with mostly other counselors, and a desire for information about illness, the services of voluntary agencies (agencies with charity status and other nonstatutory organizations), and mental health law. CONCLUSIONS: This survey highlighted the importance of meeting the information, communication, and training needs of mental health counselors in the United Kingdom in order for counselors to provide high-quality counseling services.

In the United Kingdom there has been a recent upsurge of interest in counseling, especially in primary care mental health services. This interest has been stimulated in part by a growing demand by primary care physicians for assistance in the treatment of people who have less severe mental health problems (1). Persons with previously unmet needs, for whom referral to a psychiatrist would not have been appropriate or useful because no medications were required and because the illness was not severe, are being seen by counselors. With the continuous changes that are taking place in the British National Health Service and the focus on community care, the role of counselors is developing and becoming more complex and diverse.

Although several studies have examined the cost-effectiveness and legitimacy of counseling in primary care settings, little information is available about the problems that counselors face in providing community-based mental health counseling. To be able to provide efficient services, counselors need to communicate effectively with other mental health care professionals. They also need to be aware of the presence and availability of services from various statutory and voluntary agencies (agencies with charity status and other nonstatutory organizations), both locally and nationally, and should know about mental illnesses and mental health services.

To assess knowledge in these areas, we conducted a cross-sectional survey of the communication and information needs of a random sample of counselors in the United Kingdom who were registered with the British Association of Counsellors (BAC). Specifically, we examined access to and communication with mental health professionals, barriers to providing counseling services, and predictors of information needs that would help counselors in their work.

BAC is recognized by legislators, public bodies, and members of the public as the leading voice for the counseling profession in the United Kingdom. It sets nationally recognized and consistent standards for accreditation and self-regulation of counselors. BAC membership depends on the level of training courses taken. Ordinary membership is open to individuals who have taken courses that are not accredited by BAC. Other types of members include student associates, who are taking BAC-accredited courses; counseling skills associates, who have successfully completed at least 75 hours of counseling courses; and BAC-registered associates and BAC-registered practitioners, who have passed BAC training courses or programs.

Methods

Four hundred counselors were randomly sampled from the BAC Counselling and Psychotherapy Resources Directory (2). A questionnaire was sent to each counselor, along with a letter detailing the objectives of the study and, to maximize the response rate, a postage-paid envelope. Data were collected between April 1 and November 30, 1999. Of the 400 questionnaires mailed, 230 were completed and returned, for a response rate of 58 percent.

The questionnaire covered demographic information as well as information about client caseload, communication with other professionals, information needs, and the types of information wanted. The counselors were asked about the working relationship they had with general practitioners, psychiatrists, approved social workers, registered mental health nurses, community psychiatric nurses, and other counselors.

Descriptive categorical data were presented in terms of both numbers and percentages. Descriptive numerical data were reported in terms of means and standard errors. Statistical correlation and linearity between rank-ordered variables were tested with Spearman's rho and Pearson correlation (3). Multiple logistic regression was used to investigate predictors of information needs; the dependent variable was categorized as either information needs or no information needs. The level for statistical significance was set at .05.

Results

Counselor characteristics

A total of 182 respondents (79 percent) were women. The mean±SE age of the respondents was 51±.59 years. Most respondents (223, or 97 percent) described their ethnicity as white; the remainder described their ethnicity as Indian or Pakistani. The mean±SE number of years spent practicing counseling was 13±.52. The mean±SE number of persons who were currently under the care of each counselor was 17±.83, and the mean±SE number of clients seen weekly by the counselors was 6±.56.

Relationship with other professionals

A total of 95 counselors (41 percent) reported that they had only moderate contact with other professionals, 78 (34 percent) that they had little contact, and 55 (24 percent) that they had frequent or very frequent contact. When asked what types of professionals they were mostly in contact with, 125 counselors (54 percent) mentioned other counselors, 97 (42 percent) mentioned general practitioners, 60 (26 percent) mentioned psychiatrists, 32 (14 percent) mentioned community psychiatric nurses, 9 (4 percent) mentioned approved social workers, and 6 (3 percent) mentioned registered mental health nurses.

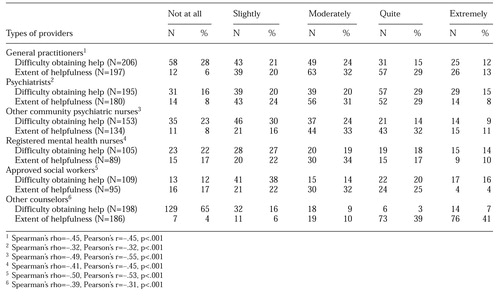

As shown in Table 1, almost two-thirds of the counselors (65 percent) reported that obtaining help from other counselors was not at all difficult, whereas only 28 percent, 23 percent, 22 percent, 16 percent, and 12 percent reported that obtaining help from general practitioners, community psychiatric nurses, registered mental health nurses, psychiatrists, and approved social workers, respectively, was not at all difficult. Most respondents (80 percent) indicated that other counselors were quite or extremely helpful when consulted. Community psychiatric nurses were rated as quite or extremely helpful by 43 percent of the respondents, general practitioners by 42 percent, psychiatrists by 37 percent, approved social workers by 29 percent, and registered mental health nurses by 27 percent. Respondents who reported difficulties in obtaining help from these professionals were significantly more likely to have reported that these professionals were less helpful in providing help when consulted.

Problems in managing cases

A total of 41 counselors (18 percent) indicated that coordination of services across professionals was quite or extremely successful for case management; 69 counselors (30 percent) reported that coordination was moderately successful, and 88 (38 percent) reported that it was slightly successful. Only 32 respondents (14 percent) reported that coordination of services was not at all successful.

Problems in achieving successful coordination of services were noted. Of the problems encountered frequently or very frequently, both lack of time and limited resources were mentioned by 131 respondents (57 percent), long waiting lists were mentioned by 115 respondents (50 percent), "too much administration or bureaucracy" was mentioned by 103 respondents (45 percent), and communication problems were mentioned by 85 respondents (37 percent).

Training and skills

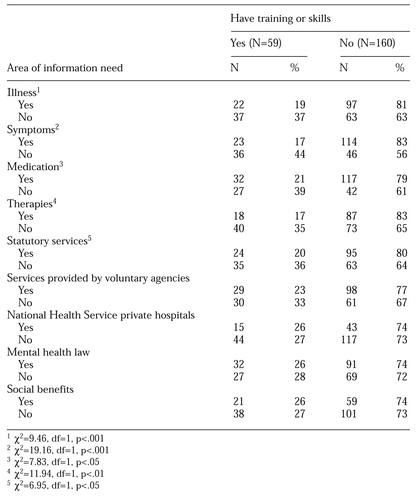

A total of 160 respondents (70 percent) reported that they did not have the necessary training or skills to successfully manage people who have severe mental health problems. As shown in Table 2, compared with respondents who reported having the necessary training or skills, respondents who reported not having the necessary training or skills were significantly more likely to have wanted information about illness, symptoms, medication, therapies, and statutory services (services provided by government agencies).

Information needs

A total of 177 counselors (77 percent) indicated that they had a need for information about mental illness. Of these, 138 (78 percent) indicated that they did not have the necessary training or skills to successfully manage severe cases of mental illness; counselors who had information needs were significantly more likely to have said that they did not have the necessary training or skills (χ2=10.49, df=1, p<.001).

A majority of all respondents reported that obtaining information was somewhat difficult: 69 (30 percent) reported that obtaining information was slightly difficult, 83 (36 percent) that it was moderately difficult, and 46 (20 percent) that it was quite or extremely difficult. Seventy-four respondents (32 percent) reported that lack of access to information or advice hindered their successful management of cases. Eighty-three counselors (36 percent) reported that their knowledge of the services provided by local statutory agencies was quite or extremely good, 53 (23 percent) that their knowledge of national statutory services was quite or extremely good, and 74 (32 percent) that their knowledge of the services provided by voluntary agencies was quite or extremely good.

The 226 respondents who reported that they had information needs were asked about the areas in which they believed they needed more knowledge. Medication ranked first (156 respondents, or 69 percent), followed by symptoms (142 respondents, or 63 percent), services provided by voluntary agencies (131 respondents, or 58 percent), mental health law (129 respondents, or 57 percent), statutory services (124 respondents, or 55 percent), illness (122 respondents, or 54 percent), therapy (108 respondents, or 48 percent), state benefits (81 respondents, or 36 percent), and National Health Service private hospitals (63 respondents, or 28 percent).

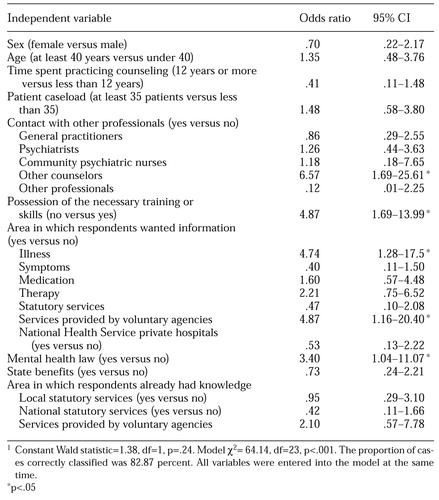

As shown in Table 3, the significant predictors of information needs were a desire for information about illness, a desire for information about services provided by voluntary agencies, a desire for information about mental health law, contact mostly with other counselors, and lack of the necessary training or skills to provide counseling to people who have severe mental health problems.

Discussion

This survey provided valuable data on the information and communication needs of mental health counselors in the United Kingdom. However, it had its limitations. Because it was a cross-sectional survey, we could draw no causal inferences between dependent and independent variables. No information was available about nonrespondents, so no conclusions could be made about the representativeness of the sample. However, our response rate (58 percent) was high relative to those usually obtained through mailed questionnaires (4).

The survey showed that a significant proportion of counselors lacked the necessary training or skills to successfully manage severe cases of mental illness, had a need for information, and had no knowledge of local or national statutory services and services provided by voluntary organizations. This lack of knowledge is of concern, especially because counseling is being requested more frequently; counseling is reported to be the method most preferred by patients for the treatment of depression (5,6), even though its effectiveness as a treatment for depressive disorders is debatable (7,8). The increase in demand for counseling has led to an increase in the number of practicing counselors (9,10), a trend that is expected to continue.

These findings indicate that it is essential to ensure that counselors have adequate training. A national survey of counselors found that many counselors who were based in general practices lacked qualifications and often had clients referred to them whose problems were outside their area of knowledge (9), which has led some authors to suggest that clients may actually be harmed rather than helped by counseling (11). Others have reported that the best safeguard of quality is to ensure that counselors meet the appropriate training standards laid down by BAC and that counselors who meet these criteria be encouraged to pursue BAC accreditation, and those who do not meet the criteria be asked to undergo further training (12). However, our findings showed that even BAC counselors—who were the subjects of this survey—reported a need for training and information about various aspects of mental illnesses, treatment, and mental health law.

In the United Kingdom, the mental health training of professionals such as community psychiatric nurses and registered mental health nurses is structured, well defined, and central to the undergraduate and postgraduate qualifications of these practitioners. There is some confusion as to the minimum qualifications required for becoming a counselor, and no training pathway or route has been defined for continuing professional development (13). In contrast, to be a licensed mental health counselor in the United States, one must meet the educational and clinical requirements of a graduate-level counselor education program (at least a master's degree), pass a government-administered examination, and accumulate an average of more than 2,000 hours of postdegree supervised clinical experience (personal communication, Freeman L, American Counseling Association, 2001).

Progress could be made in the United Kingdom by conducting panel discussions and focus groups with counselors to elicit their views about the content and structure of a standard comprehensive training program in mental health counseling, which should include, in addition to counseling skills and psychological theories, modules on mental illnesses, treatment, mental health law, and mental health services.

Another main finding of our survey was that many counselors reported that they had little contact with other health care professionals. This finding is consistent with evidence that communication between health professionals in several health care delivery systems is currently chaotic (14) and that patients could be at risk (15). It has been argued that multidisciplinary teams of professionals may have difficulty communicating because of inconsistent theoretic underpinnings and that a theoretic base that spans both clinical outcomes and professional boundaries is needed (16). Nevertheless, it is essential that counselors increase their level of communication with other health professionals so that all aspects of care can be integrated in a manner that leads to enhanced patient satisfaction, higher quality of life, and better mental health status.

The survey also identified problems in the relationship between counselors and general practitioners. A national survey of counselors revealed general practitioners' lack of awareness of the qualifications of counselors in their practices and highlighted the need for general practitioners to be more discriminating in their referral policies if they are to maximize the benefits of their counseling services (9). However, general practitioners have reported being in favor of having counselors based in their practices (9,17). Although no information was collected about whether counselors were attached to general practices, respondents indicated problems in gaining access to and communicating with general practitioners. We recommend a relationship based on sharing of information between counselors and general practitioners in order to provide a tailored package of treatment to clients that ensures that no mentally ill person slips through the net of community care. Strategies for breaking down barriers to access and communication should be developed through consultation with counselors and general practitioners and consideration of the heavy workloads and time restrictions faced by both types of providers.

Conclusions

This national survey showed that mental health counselors in the United Kingdom need more training in mental illnesses, treatment, and mental health law. Efforts should also be made to increase counselors' access to and communication with other health care professionals, especially general practitioners.

Acknowledgments

This survey was conducted by SANE, a United Kingdom mental health charity, and was financially supported by an educational grant from Pharmacia and Upjohn.

Dr. Fakhoury is lecturer in social psychiatry at the unit for social and community psychiatry of St. Bartholomew's and the Royal London School of Medicine, Academic Unit, East Ham Memorial Hospital, Shrewsbury Road, London E7 8QR, United Kingdom (e-mail, [email protected]). Ms. Wright is a researcher at SANE, a national mental health charity in the United Kingdom, based in London.

|

Table 1. Difficulty obtaining the help of other professionals and extent of helpfulness of professionals, as reported by 230 counselors in the United Kingdom who responded to a mailed questionnaire

|

Table 2. Information needs reported by 226 counselors in the United Kingdom who responded to a mailed questionnaire, by whether respondents reported having the necessary training or skills to manage patients who have severe mental illness

|

Table 3. Multivariate associations predicting the information needs of 175 counselors in the United Kingdom1

1 Constant Wald statistic=138, df=1, p=.24. Model χ2 = 64.14, df=23, p<.001. The proportion of cases correctly classified was 82.87 percent. All variables were entered into the model at the same time.

1. Jenkins G: Collaborative care in the United Kingdom. Primary Care 26:411-422, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Palmer I: Counselling and Psychotherapy Resources Directory for Counsellors, Psychotherapists, Counselling Supervisors, Trainers. London, British Association for Counselling, 1998Google Scholar

3. Freund R, Wilson W: Statistical Methods, rev ed. San Diego, Calif, Academic Press, 1997Google Scholar

4. Bowling A: Research Methods in Health: Investigating Health and Health Services. Buckingham, United Kingdom, Open University Press, 1981Google Scholar

5. Priest R, Vize C, Roberts A: Lay people's attitudes to treatment of depression: results of opinion poll for Defeat Depression Campaign before its launch. British Medical Journal 313:858-859, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Dwight-Johnson M, Sherbourne C, Liao D, et al: Treatment preferences among depressed primary care patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine 15:527-534, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Tylee A: Counselling in primary care. Lancet 350:1643, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Churchill R, Dewey M, Gretton V, et al: Should general practitioners refer patients with major depression to counsellors? A review of current published evidence. Nottingham Counselling and Antidepressants in Primary Care (CAPC) Study Group. British Journal of General Practice 49:738-743, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

9. Sibbald B, Addington-Hall J, Brenneman D, et al: Counsellors in English and Welsh practices: their nature and distribution. British Medical Journal 306:29-33, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. South West Research and Development Directorate: Counsellors in Primary Care: Developments and Evaluation Committee Report Number 40. Bristol, United Kingdom, National Health Service, 1995Google Scholar

11. Corney R: The effectiveness of counselling in general practice. International Review of Psychiatry 4:331-338, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Clark A, Hook J, Stein K: Counsellors in primary care in Southampton: a questionnaire survey of their qualifications, working arrangements, and casemix. British Journal of General Practice 47:613-617, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

13. Eatock J: Counselling in primary care: past, present, and future. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling 28:161-173, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Clinical Systems Group: Improving Clinical Communications. Sheffield, United Kingdom, Centre for Health Information Management Research, 1998Google Scholar

15. Salter R, Brettle P, Hobbs F, et al: Poor communication puts patients at risk [letter]. British Medical Journal 317:279, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Milligan R, Gilroy J, Katz K, et al: Developing a shared language: interdisciplinary communication among diverse health care professionals. Holistic Nursing Practice 13(2):47-53, 1999Google Scholar

17. Baker R, Allen H, Gibson S, et al: Evaluation of a primary care counselling service in Dorset. British Journal of General Practice 48:1049-1053, 1998Medline, Google Scholar