The Prevalence of Religious Coping Among Persons With Persistent Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to examine the prevalence of religious coping among persons with persistent mental illness and to gain a preliminary understanding of the relationship between religious coping and symptom severity and overall functioning. METHODS: A total of 406 individuals who were diagnosed as having a mental illness and who were patients at one of 13 Los Angeles County mental health facilities completed a survey consisting of the Religious Coping Index, the Symptom Checklist 90-R (SCL-90), the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale, and a 48-item demographic questionnaire. RESULTS: More than 80 percent of the participants used religious beliefs or activities to cope with daily difficulties or frustrations. A majority of participants devoted as much as half of their total coping time to religious practices, with prayer being the most frequent activity. Specific religious coping strategies, such as prayer or reading the Bible, were associated with higher SCL-90 scores (indicating more severe symptoms), more reported frustration, and a lower GAF score (indicating greater impairment). The amount of time that participants devoted to religious coping was negatively related to reported levels of frustration and scores on the SCL-90 symptom subscales. CONCLUSIONS: The results of the study suggest that religious activities and beliefs may be particularly compelling for persons who are experiencing more severe symptoms, and increased religious activity may be associated with reduced symptoms. Religion may serve as a pervasive and potentially effective method of coping for persons with mental illness, thus warranting its integration into psychiatric and psychological practice.

When mental health care professionals consider the coping strategies used by persons with mental illness, religion may not be the first mechanism that comes to mind. In fact, little attention has been given to adaptive forms of religious coping in this population. Many professionals view religious coping with ambivalence or believe that it is inconsequential in understanding mental illness (1).

The mental health field has created a plethora of sophisticated treatment strategies and a highly systematized base of clinical knowledge that has—perhaps inadvertently—neglected to take into account the personal resources and meaningful strategies used by persons with mental illness to sustain coping ability and strength. One of these strategies is religious coping, and an examination of its prevalence seems increasingly necessary.

The limited research that does exist on religious coping among persons with persistent mental illness suggests that it may be a salient and prevalent method for enduring chronic psychiatric symptoms and concomitant life frustrations. Kroll and Sheehan (2) found that 95 percent of the psychiatric inpatients in their study (N=52) professed a belief in God, and 53 percent prayed or consulted the Bible—rates similar to those in the general population (3). In a comparison of psychiatric patients and a nonpsychiatric control group, it appeared that the psychiatric patients had a larger number of religious beliefs and practices that offered comfort during stressful life experiences (4).

Religious forms of coping may be particularly relevant and compelling for persons with schizophrenia (5,6), recurrent major depression (7), and other forms of severe mental illness because of the overall loss of hope, control, and purpose that these illnesses may engender. In fact, Lindenthal and associates (8) found that more internal or personal forms of religious expression, such as prayer, may come to the foreground as coping strategies precisely when psychological impairment and life crises increase. Sullivan (9) found that almost half of a group of 40 psychiatric outpatients perceived their spiritual beliefs and practices as crucial to their psychiatric improvement.

Religious practices and beliefs may play an integral role in sustaining adequate adjustment to severe and persistent mental illness (7) by serving as a buffer against the progression of decompensation (10) and by enabling individuals to cope with the ongoing interference of symptoms in their daily lives. However, basic information about their prevalence for coping purposes and their overall relationship to severity of symptoms and functioning has yet to be determined (11).

The importance of such research is underscored by the fact that professional organizations such as the American Psychiatric Association and the American Psychological Association now encourage the assessment and incorporation of adaptive religious repertoires into treatment planning and intervention (12). In order to improve treatment planning and intervention, mental health professionals need to increase their communication with persons who have mental illness and who have acquired and maintained a lifestyle of adaptive religious coping. Such a dialogue may prove to be a rich resource for discovering more meaningful ways to manage the debilitating, long-term effects of severe mental illness.

After many years of clinical work with clients suffering from severe and persistent mental illness, and recognizing the paucity of knowledge about religious coping among the mentally ill, we could no longer ignore the need to empirically inquire into patients' use of adaptive religious coping. We wanted to determine the prevalence of religious coping among persons with severe and persistent mental illness and the most frequently used practices or beliefs. We also sought to gain a preliminary understanding of the relationship between such coping and symptom severity and daily functioning.

Methods

Participants

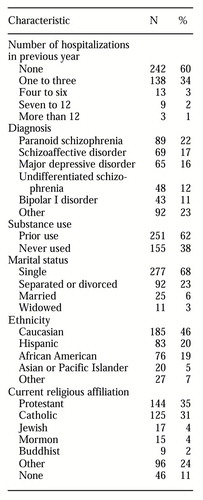

Between June 1998 and October 1999, we surveyed 406 mental health consumers who had been diagnosed as having persistent mental illness and who were attending one of 13 Los Angeles County mental health facilities, including four board-and-care units. Of the 406 participants, 238 (59 percent) were men and 168 (41 percent) were women. Their mean±SD age was 40.9±10.7 years, and their average Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) (13) score was 38.2± 8.4. They averaged 18.5±12.7 years of mental illness and had a lifetime average of 5.68±9.17 hospitalizations for mental illness. Ninety-three percent of the participants reported that they were taking medications on a daily basis. Additional characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Participation in the study was contingent only on the client's informed and voluntary consent.

Measures

The prevalence of religious coping was assessed by asking the participants to complete a 48-item demographic survey. The survey included items that assessed the total number of years the participants had used religious coping and the perceived importance of religion when their symptoms worsened. Types of religious activities or strategies were determined by providing the participants with a list of eight religious activities, ranging from prayer to meeting with a spiritual leader, and asking them to check the ones they used.

Participants were also interviewed with an adapted version of Koenig's (7) Religious Coping Index (RCI). The RCI is a simple, three-item questionnaire developed for use with persons with severe medical illness, including mental illness. The RCI was also used to measure the extent to which participants relied on religious activities and beliefs and their perceived helpfulness as an aid for coping. One item was added to the RCI to determine what proportion of total coping time was spent on religious coping.

To assess symptom severity and overall functioning, participants completed a large-font version of the Symptom Checklist 90-R (SCL-90) (14), which is a 90-item index demarcated into ten subscales designed to assess severity of symptoms within the past seven days. These subscales included somatization, obsessive-compulsiveness, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. Subscale scores were calculated by summing responses to the subscale items, which ranged from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely), in assessing the degree to which participants were distressed by the difficulties or problems indicated in each item. Internal consistency coefficients on the subscales ranged from .83 to .93.

Symptom severity and overall functioning were also assessed by the participants' current level of frustration, their total number of hospitalizations for mental illness in the past year, and their current GAF score. Level of frustration was measured by asking participants the degree to which they had current frustrations or difficulties, with potential responses ranging on a 5-point scale from "none" to "I have many frustrations or difficulties constantly, and they never seem to get better." GAF scores were obtained from the participants' medical charts. (GAF scores can range from 1 to 100, with higher scores indicating better functioning.) If the charts lacked GAF scores or reflected scores that were more than six months old, the interviewers extracted clinical information from chart notes, SCL-90 responses, and behavior during the interview to estimate a current GAF score.

Three interviewers who had received training on each measure administered the surveys to the participants in scheduled treatment groups or site meetings at each county facility.

Data analysis

The prevalence of religious coping was determined by computation of descriptive statistics for each measure, including means and relative frequencies. The relationship between each specific strategy and each symptom measure was evaluated with independent-samples t tests. Pearson product-moment correlations were used to determine the relationship between each symptom measure and the measures that assessed the amount of time devoted to religious coping. However, the potential variation in symptoms across perceived differences in the importance of religion as symptoms worsen was assessed with a univariate analysis of variance. The Scheffé test was subsequently used to assess post hoc comparison of means. Given the exploratory nature of these analyses, an alpha level of .05 or less was considered significant.

Results

Prevalence of religious coping

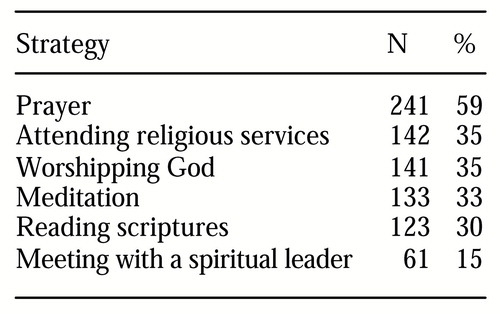

Overall, 325 of the 406 participants (80 percent) reported using some type of religious activity or had some type of religious belief that helped them cope with their symptoms and frustrations or difficulties. A total of 373 (92 percent) reported using a religious activity, and 296 (73 percent) had some type of religious belief. A total of 246 participants (61 percent) devoted as much as half of their total coping time to religious practices, and they reported having engaged in such coping for a mean±SD of 16± 17.65 years. As shown in Table 2, prayer was the most common type of religious activity, followed by attending religious services and worshipping God.

Religious coping and symptom severity

A total of 264 participants (65 percent) reported that religion helped them to either a moderate or a large extent in coping with symptom severity, and 120 (30 percent) indicated that their religious beliefs or activities "were the most important things that kept [them] going." In fact, 193 participants (48 percent) indicated that religion became more important to them when their symptoms worsened.

Participants were divided into three groups according to their perception of whether religion became more important when their symptoms worsened. The groups differed significantly in total number of hospitalizations during the previous year (F=7.09, df=2, 397, p<.001). In particular, a Scheffé test revealed that, on average, participants who reported that religion became more important when their symptoms worsened experienced fewer hospitalizations in the previous year than those for whom religion became less important when symptoms worsened (.44± .71 versus .88±.9 hospitalizations).

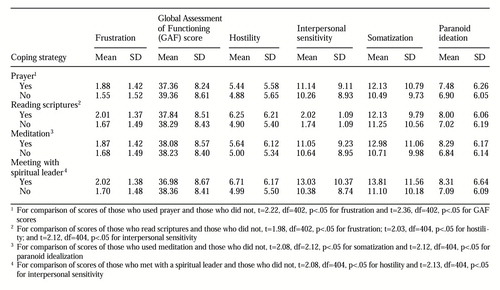

Inferential analyses of the relationship between religious coping and symptom severity suggest that specific strategies, such as prayer or reading the Bible, were more likely to be used by participants who were experiencing more severe symptoms and lower levels of overall functioning. As shown in Table 3, participants who reported using prayer as a strategy to cope with their difficulties were significantly more likely to experience a greater level of frustration and have a lower GAF score. Those who coped by reading the Bible reported higher levels of frustration, hostility, and interpersonal sensitivity. Meeting with a spiritual leader was associated with higher levels of hostility and interpersonal sensitivity, and meditation was associated with higher levels of somatization and paranoid ideation.

Although the remaining relationships between specific religious strategies and measures of symptom severity were not significant, it appears that the participants who were experiencing greater debilitation and more impaired functioning were more likely to use specific religious coping strategies.

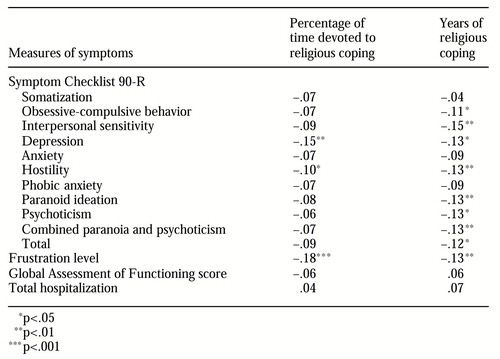

A different pattern emerged in the relationship between symptoms and the amount of time devoted to religious coping (Table 4). Both the number of years that religious coping had been used and the percentage of overall coping time devoted to religious coping were correlated with less severe symptoms and better overall functioning. A greater number of years of religious coping and a greater percentage of overall coping time devoted to religious coping were both associated with lower levels of depression, hostility, and frustration. A greater number of years of religious coping was also correlated with lower symptom levels in six areas—obsessive-compulsiveness, interpersonal sensitivity, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, psychoticism, and total symptomatology. No significant relationships were found between religious coping and GAF scores or total number of hospitalizations.

Discussion

Religious activities and beliefs may function as a pervasive and potentially effective method of coping for persons with severe and persistent mental illness. Compared with the 20 to 60 percent of the general population who report using religion as a means of coping (7), 80 percent of the participants in our study used some type of religious belief or activity to cope with their symptoms and daily difficulties; 60 percent devoted as much as half of their total coping time to religious forms of coping. As in the study by Lindenthal and associates (8), prayer was found to be the most commonly used coping strategy, followed by attending religious services and worshipping God. Collectively, these results suggest that religious methods of coping may be particularly salient for persons with mental illness, and they may serve as one of the more important strategies that enable these persons to persevere.

Furthermore, it appears that the use of specific religious coping strategies, such as prayer or meditation, is more common among persons with more severe levels of suffering. Nearly half of the participants in our study claimed that religion became more important when their symptoms became worse, and 30 percent indicated that it was the foremost coping method they used to keep them going. This finding suggests that persons who are experiencing greater debilitation and distress may be more likely to rely on and report using religious coping strategies. Lindenthal and associates (8) reported similar findings.

Religious activity may impart a sense of control and meaning by affording a perspective beyond oneself. When confronted with severe distress, suffering, and personal limitation, individuals with mental illness may have exhausted other resources and consequently find solace in looking beyond themselves for hope, power, and maybe even a nonreductive understanding of their debilitation (15).

Taken together, the association between greater time devoted to religious coping and reduced symptom severity and the finding that specific religious strategies were more frequently used by persons with more severe symptoms suggest an interesting trend. Times of crisis may prompt the use of specific religious strategies such as prayer or meditation, but with repeated use of these strategies over time, the overall severity of symptoms may lessen. The fact that participants for whom religion became more important when their symptoms worsened had fewer hospitalizations in the previous year support this interpretation.

Alternatively, it is possible that the relationship we observed between the amount of time devoted to religious coping and reduced symptom severity was simply a function of a normal regression to the mean, and the participants simply got better over time. Nevertheless, the results of our study seem to indicate that religious activities and beliefs are coping mechanisms that persons with mental illness use and find beneficial in managing the symptoms and stressors of their illness.

It is also interesting that four of the five most commonly used strategies involve highly personal and internalized dimensions of coping. Consistent with the findings of Lindenthal and colleagues (8), the participants in our study tended to shy away from external or social forms of religious coping, preferring instead the internal and subjective activities of prayer, worshipping God, meditation, and reading scriptures. Although further research is needed to examine this finding empirically, it may indicate a more personal or internal style of religious coping in this population.

When considering the results and implications of this study, readers should keep its limitations in mind. First, by design the study was intended to be exploratory and thus lacked the discipline of an experimental design that might control for alternative explanations of the findings. Second, individuals who are suffering from mental illness may be particularly vulnerable to social desirability in their reporting, especially considering the presupposed benefits for their treatment that might come from presenting themselves as having fewer symptoms or as being particularly religious or nonreligious. This vulnerability may have specifically affected responses on the SCL-90 and contributed to a test-taking strategy of reporting only minimal symptoms.

Third, given the voluntary nature of our study, our sample may reflect a bias toward persons who were willing to discuss their religious activities and beliefs and may have inadvertently overrepresented persons who are strongly religious or who are impassioned against religion. Moreover, our study did not explore how such religious coping was used—be it toward adaptive ends or in service to the mental illness itself.

Finally, greater standardization in our survey instruments might lead to greater confidence in our findings. For example, the use of observer-rated instruments could reduce the confounding impact of cognitive and affective impairment on self-reported measures.

Conclusions

The findings of this study seem to highlight the importance of religion as a significant coping strategy for persons with mental illness and suggest that we, as mental health providers, need to afford religious coping a natural place in treatment, assessment, and research. This strategy can be incorporated into clinical interviews and integrated into treatment planning, matching, and follow-up. We need to introduce the positive psychology of religious coping into our assessment practices, asking clients about the ways in which they are religious, what purpose religion serves in their lives, and how religion is connected with their coping with mental illness. Such assessments would also examine the effectiveness of current religious coping practices and how they may change during episodes of symptom exacerbation.

Furthermore, contextual implications call for more intentional outreach to persons who desire greater contact with religious communities and organizations. The fact that only 35 percent of our participants attended religious services to deal with their frustrations and only 15 percent met with a spiritual leader to aid in coping suggests the need for new models of service provision. Mental health professionals may need to reach out to churches and clergy to try to facilitate communications between pastoral counselors and church laity (16). Public efforts should be made to educate and promote a culture of inclusiveness, calling for a greater awareness of mental illness in the community at large.

Research on the relationship between religious coping and symptom levels should be expanded to include an experimental time-series design that assesses the efficacy of religious coping over time, more standardized and observer-rated instruments that correct for underreporting, and an examination of the internal and external dimensions of the religious coping used by this population. Moreover, length of stay in the community, overall participation in treatment, and psychopharmacological intervention as they are related to religious life and coping are areas for immediate consideration and study. Together, such clinical efforts and research could facilitate both a positive understanding of the religious life of persons with mental illness and a positive dialogue for providers who need to find and use more meaningful coping strategies in the treatment of mental illness.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Greg Reger, M.A., and Evelyn Poey, M.A., for their efforts and contributions to this paper.

Dr. Tepper and Dr. Coleman are licensed clinical psychologists in the Pasadena and Los Angeles areas, respectively. Mr. Rogers is a research assistant at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Malony is senior professor of psychology in the graduate school of psychology at Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena. Findings from this research were presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association held August 4-8, 2000, in Washington, D.C. Address correspondence to Dr. Tepper at 595 East Colorado Boulevard, Suite 622, Pasadena, California 91101 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 406 persons with persistent mental illness who participated in a study of the prevalence of religious coping

|

Table 2. Religious coping strategies used by 406 persons with persistent mental illness to deal with symptoms

|

Table 3. Mean scores on measures of symptoms for persons with persistent mental illness who did or did not perform religious coping activities (total N=406)

|

Table 4. Correlations between measures of symptoms and religious coping over time for 406 persons with persistent mental illness

1. The Psychic Function of Religion in Mental Illness and Health. GAP Report 6. New York, Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry, Committee on Psychiatry and Religion, 1968, pp 653-727Google Scholar

2. Kroll J, Sheehan W: Religious beliefs and practices among 52 psychiatric inpatients in Minnesota. American Journal of Psychiatry 146:67-72, 1989Link, Google Scholar

3. Gallup GH: Religion in America:1992-1993. Princeton, NJ, Gallup Organization, 1993Google Scholar

4. Neeleman J, Lewis G: Religious identity and comfort beliefs in three groups of psychiatric patients and a group of medical controls. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 40:124-134, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Wahass S, Kent G: Coping with auditory hallucinations. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 185:664-668, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Walsh J: The impact of schizophrenia on clients' religious beliefs: implications for families. Families in Society 76:551-558, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Koenig JG: Aging and God: Spiritual Pathways to Mental Health in Midlife and Later Years. New York, Haworth Pastoral Press, 1994Google Scholar

8. Lindenthal JJ, Myers JK, Pepper MP, et al: Mental status and religious behavior. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 9:143-149, 1970Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Sullivan WP: "It helps me to be a whole person": the role of spirituality among the mentally challenged. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 16:125-134, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Jahangir SF: Third force therapy and its impact on treatment outcome. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 5:125-129, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Crossley D: Religious experience within mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry 166:284-286, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Waldfogel S, Wolpe PR: Using awareness of religious factors to enhance interventions in consultation-liaison psychiatry. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:473-477, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

13. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

14. Derogatis LR: SCL-90R: Symptom Checklist-90-R. Minneapolis, Minn, National Computer Systems, 1994Google Scholar

15. Pargament KI: Religious methods of coping: resources for the conservation and transformation of significance, in Religion and the Clinical Practice of Psychology. Edited by Shafranske EP. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1996Google Scholar

16. Meylink WD, Gorsuch RL: Relationship between clergy and psychologists: the empirical data. Journal of Psychology and Christianity 7:56-72, 1989Google Scholar