Variations in the Treatment Culture of Nursing Homes and Responses to Regulations to Reduce Drug Use

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study examined the relationship between treatment cultures of nursing homes and their responses to regulations to reduce use of psychotropic drugs mandated by the 1987 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act. The authors hypothesized that reduction in use of antipsychotic drugs was more likely to occur in homes with a resident-centered culture emphasizing psychosocial care, avoidance of psychotropic drugs, pharmacist feedback, and involvement of mental health workers. The authors also predicted greater reductions in drug use in facilities with a less severe case mix and better capacity for change. METHODS: Data were collected in a stratified random sample of 16 skilled nursing facilities in Wisconsin. Participants included 1,181 residents in the baseline study and 1,650 residents in the follow-up study. Treatment culture was measured with a questionnaire for assessing nurses' beliefs and philosophies of care and their interactions with pharmacists and mental health workers. RESULTS: No significant change was observed in the use of benzodiazepines, antidepressants, or polymedicine (two or more psychotropic medications). However, use of antipsychotic drugs decreased significantly, from 24 percent to 16 percent. The change in use varied dramatically across facilities, from an 85 percent reduction to a 19 percent increase. Findings also revealed significant variability in treatment cultures. Greater reductions in use of antipsychotic drugs were found in facilities with a resident-centered culture, a less severe case mix, and a higher nurse-to-resident staffing ratio. CONCLUSIONS: Future policy and quality improvement efforts must address treatment cultures, staffing, and other organizational barriers to nursing home reform.

The overuse of psychotropic drugs in nursing homes has been a concern for decades (1,2,3). In 1987 Congress mandated stricter regulations to reduce unnecessary drug use as part of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA). The first set of regulations, implemented in 1990, focused on antipsychotic drugs, which often were used to control the behavior of nursing home residents despite concerns about adverse effects and lack of efficacy (4). The second set of regulations (5), implemented in 1992, focused on benzodiazepines, which were used routinely despite concerns about hip fractures related to their use and other adverse drug effects (6).

Several studies have evaluated the effects of the new regulations and have found that the use of antipsychotic drugs was reduced by 27 to 36 percent (3,7,8,9,10). However, few studies have been conducted since 1992. Studies also showed extraordinary variation in facilities' responses to the regulations (7,8). For example, Tennessee researchers (8) found that one- fourth of their facilities reduced use of antipsychotic drugs by 46 percent or more, one-fourth had no change or an increase in use, and one-half fell between these extremes. Studies examining the organizational factors associated with change would help us understand and address these factors in future improvement efforts.

Researchers have examined organizational factors associated with change in the use of physical restraints (11), but little is known about the organizational factors associated with reduction of drug use. One hypothesis is that the variation in drug use across facilities is simply a function of case mix. Only one post-OBRA study has examined this hypothesis at the facility level. Minnesota researchers (9) found greater use of antipsychotics in facilities with younger residents and residents with psychiatric illnesses; however, these factors did not fully explain differences in drug use across facilities.

Two post-OBRA studies have examined staffing differences, but the results are ambiguous. The first study found a significant relationship between third-shift staffing and drug reduction, but the study did not report information about diagnoses and other potential confounders (8). The second study found no significant effects for various staffing categories, but it did not examine the overall effects of staffing (9). Others have speculated that successful reform requires stable leadership by directors of nursing (12), better reimbursement (13), and a "resident-centered" culture emphasizing restraint-free care and collaboration among providers (3,14,15). However, we found no empirical studies examining these factors.

In this study, we examined four types of factors that can influence an organization's ability or motivation to change: need, structure, capacity, and culture. The need hypothesis suggests that reduction in the use of drugs will be greater in facilities in which residents have lower rates of mental illness or a lower potential need for medication (9). The structure hypothesis suggests that reduction in drug use will be greater in facilities with structural features believed to facilitate change, such as smaller size and nonprofit ownership (16). The capacity hypothesis suggests that reduction of use will be greater in facilities with better human and financial capacity for change, such as better staffing, leadership, and reimbursement (8,12,17,18).

The culture hypothesis suggests that reduction in drug use will be greater in facilities that have an organizational culture that is compatible with new guidelines (19). Organizational culture has been defined as the "values, beliefs, and norms of an organization that shape its behavior" (20). It can be studied by surveying the beliefs of staff members and their interactions with each other and with clients (21).

Little is known about nursing home cultures. However, it is believed that facilities have different philosophies for managing dementia or mental illness (14,15,22) and that a resident-centered philosophy is essential for reform (3). The term "resident-centered philosophy" describes beliefs and norms that emphasize individualized assessment and psychosocial care, avoidance of restraints, and multidisciplinary collaboration. In contrast, a traditional philosophy emphasizes custodial care, behavioral control, and little collaboration among staff and other providers. Given the OBRA regulations' emphasis on reducing drug use in nursing homes, we hypothesized that greater reductions would occur in homes with a resident-centered culture.

Methods

Sample

Data were obtained from a larger baseline study conducted between 1986 and 1989 (23) and a follow-up conducted between 1993 and 1994 (the study reported here). The baseline study examined a stratified random sample of 18 Medicaid-certified skilled nursing facilities with proprietary or nonprofit religious auspices, 60 or more beds, and unit-dose systems that involved prepackaged doses for administration by nurses from medication carts. Facilities were stratified by auspices (proprietary and nonprofit religious) and percentage of private-pay residents (below and above the mean for the region). Characteristics of participating and nonparticipating homes are described elsewhere (23).

Administrators in the 18 homes contacted all 2,434 residents or the residents' guardians. Of these, 257 (11 percent) refused, and 117 (5 percent) became ineligible because of death, hospitalization, discharge, or relocation. Because we were unable to collect follow-up data for private-pay residents, this analysis was restricted to 1,181 Medicaid-funded residents at baseline and 1,650 Medicaid-funded residents at follow-up. Two facilities were excluded because they had fewer than ten Medicaid recipients.

Drug use

For each of the 16 facilities in this study, we calculated the percentage of residents receiving antipsychotics, antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and polymedicine (two or more psychotropic drugs) during the baseline and follow-up periods. We also calculated the proportional change in use of antipsychotic drugs, which was the difference between baseline and follow-up, divided by baseline, and multiplied by 100. Pharmacy records were used to assess baseline drug use, and Medicaid claims were used to assess drug use at follow-up. Researchers have compared these data sources and found them to have good accuracy (24).

Resident mix

Resident mix at the 16 facilities was measured through medical records, Wisconsin Annual Nursing Home Surveys, Medicaid claims, and nurse assessments. Medical records provided a measure of the number of residents diagnosed as having dementia at baseline; the Wisconsin surveys provided aggregate measures of age, gender, and serious mental disorders in 1989 and 1993; and Medicaid claims provided a global measure of serious mental disorders or alcohol or other drug abuse in 1993. Serious mental disorders included organic and nonorganic psychotic conditions and Alzheimer's disease (ICD-9 codes 290 to 298, and 331).

One nurse from each unit was asked to assess each resident's behavior at baseline using a brief resident assessment form. The nurse rated each resident on a 3-point scale in terms of how often the resident was agitated, noisy or disruptive, physically aggressive, or physically resistive to care in the past month (1, rarely; 3, usually). Items were summed to create a total score ranging from 4 to 12. Interrater reliability was assessed on the basis of independent ratings of 114 residents by two nurses. Interrater gammas ranged from .85 to .96 (mean=.93), indicating good interrater reliability for each item, and the Pearson correlation for the total score was .84, indicating good interrater reliability for the four-item scale. Scores were aggregated to obtain a facility mean.

Structure and capacity for change

State surveys and administrative records provided baseline and follow-up measures of facility structure and capacity for change. Structural measures included number of licensed beds and ownership type (for-profit versus nonprofit religious). Capacity measures included per diem Medicaid reimbursement for skilled care in dollars, number of licensed nurse full-time equivalents per resident, and stability of nursing leadership. Nursing leadership stability was measured by counting the number of nursing directors each facility had during the four-year period before implementation of OBRA. Facilities with three or more nursing directors were defined as having low stability, and those with one or two were defined as having high stability.

Finally, we created a summary measure of each facility's capacity for change by classifying it according to whether it fell below or above the median on three capacity measures at baseline (low-high reimbursement, low-high staffing, low-high nursing leadership stability). One point was assigned for each measure that fell above the median; the possible range of scores was 0 to 3, with 3 indicating a higher capacity for change.

Treatment culture

Evening and night nurses completed a nurse medication questionnaire about treatment beliefs and interactions with residents and other providers at baseline. Evening nurses were targeted because the larger study focused on sleep problems. A $10 honorarium and two reminders yielded a 75 percent response rate.

Respondents included 89 registered nurses and 102 licensed practical nurses. The nurse medication questionnaire assessed three elements of a resident-centered culture versus a traditional culture as described in the literature (3,14,15). These elements included the nurse's philosophy about drug use, the pharmacist's feedback about drug use, and the involvement of mental health workers.

A 12-item medication philosophy scale was developed and used for measuring nurses' beliefs and norms about drug and nondrug interventions for managing behavior and sleep problems. Scores were standardized and aggregated to create a facility mean. Positive scores indicated a resident-centered philosophy favoring psychosocial care as opposed to drug use, and negative scores indicated a traditional philosophy favoring drug use as opposed to psychosocial care. Internal consistency was good (Cronbach's alpha=.72). An earlier version of the scale was a strong predictor of whether nurses administered hypnotics, which suggested good predictive validity (25). (A copy of the items and scoring procedures may be obtained from the first author.)

Pharmacist feedback was measured by three items that asked nurses about their awareness of pharmacist reviews, the pharmacist's drug use review criteria, and how often nurses were informed of results from the pharmacist's drug use review. Items were standardized and aggregated to create a facility mean, with positive scores indicating higher pharmacist feedback to nurses. Internal consistency was good (Cronbach's alpha=.77). The involvement of mental health workers was measured by a single item that asked nurses to evaluate mental health workers' involvement in their facility on a 5-point scale ranging from poor to excellent.

Finally, we created a composite measure of treatment culture by classifying each facility according to whether it fell below or above the median on the three cultural elements. Scores ranged from 0 to 3, with 3 indicating a stronger resident-centered culture.

Statistical analysis

We began by examining the characteristics of the 16 nursing homes and variations in their cultures. Levels of psychotropic drug use at baseline and follow-up were analyzed with paired t tests using a significance level of .05 and with the facility as the unit of analysis. We then tested directional hypotheses with one-tailed t tests and multiple regression techniques. Although the multiple regression analyses lacked statistical power because of the small number of facilities in the sample, they provided a more conservative test of the hypotheses.

Results

Facility characteristics

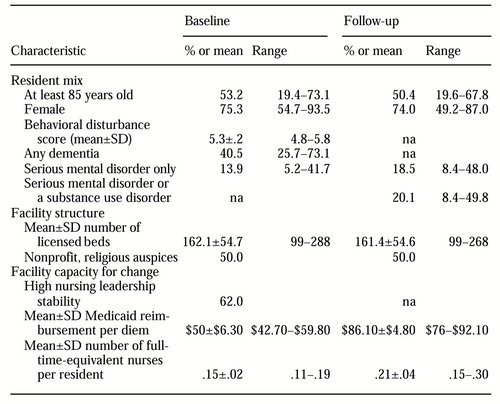

Table 1 summarizes data on the characteristics of the 16 nursing homes at baseline and follow-up. Three-fourths of the residents were women. Half of the residents were 85 years of age or older (mean±SD age of 82.7±4.5 at baseline). Behavioral and mental health problems were common at baseline and follow-up. The sample included eight for-profit facilities and eight nonprofit facilities and was diverse in resident mix, number of beds, nursing leadership stability, Medicaid reimbursement, and staffing.

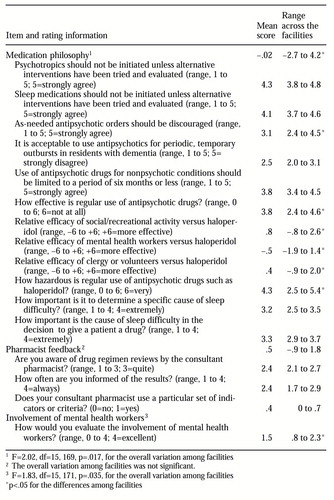

As Table 2 shows, data from the survey of nurses revealed substantial variability in treatment culture across the 16 facilities. For example, nurses' beliefs about as-needed antipsychotic medications ranged from a mean of 2.4 to 4.5 across the 16 facilities, a significant variation. Nurses' beliefs also varied significantly about the relative efficacy of psychosocial care compared with the use of antipsychotic medication, the hazardousness of antipsychotics, and the overall medication philosophy score (F=2.02, df=15, 169, p<.05).

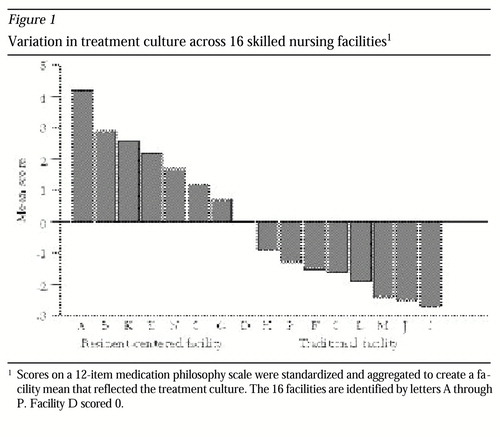

Figure 1 illustrates the wide variability in medication philosophy by facility. Five facilities—A, B, K, E, and N—had a more resident-centered philosophy (a rating of 1.7 or higher). Five facilities—C, L, M, J, and I—had a more traditional philosophy (a rating of -1.6 or lower). Six facilities—O, G, D, H, P, and F—had a mixed or ambiguous philosophy that fell between these extremes.

In general, nurses were critical about the quality of mental health workers' involvement, although nurses at some facilities rated such involvement better than nurses at other facilities (F=1.83, df=15, 171, p<.05). The scores on pharmacist feedback also indicated some variation (range= -.9 to 1.8), although the differences between facilities were not significant. Most nurses were aware of pharmacist reviews, but only 40 percent were familiar with their criteria, and they were not always informed about results.

Changes in drug use

The results showed nonsignificant changes from baseline to follow-up in benzodiazepine use; at baseline 18.1 percent of patients were taking benzodiazepines, compared with 22.8 percent at follow-up. The rates for antidepressant use were 17 percent and 21.1 percent, respectively, and the respective rates for polymedicine were 14.7 percent and 14.4 percent.

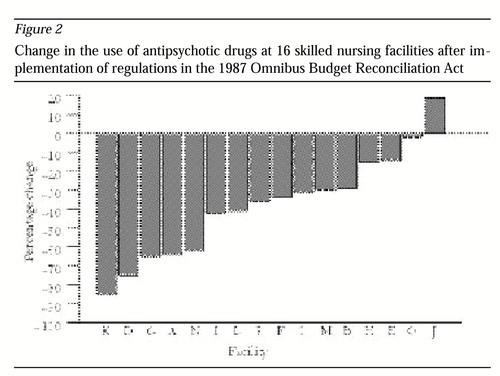

In contrast, use of antipsychotic drugs decreased from 24 percent at baseline to 15.6 percent at follow-up (t=-5.35, df=15, p<.001). Figure 2 shows the change in use of antipsychotic drugs in the 16 facilities. The change in use varied dramatically across facilities (a mean reduction of 38 percent; range, a reduction of 85.4 percent to an increase of 18.8 percent). At five nursing homes—facilities K, D, G, A, and N—use of antipsychotics decreased by 60 percent or more; at three homes—H, E, and O—it decreased by 15 percent or less, and at seven homes the decrease was between these extremes. Use of antipsychotics increased at one home.

Predictors of change inuse of antipsychotic drugs

We compared the proportional change in use of antipsychotic drugs in nursing homes below and above the median on various predictors. The results showed nonsignificant associations between a reduction in use of antipsychotics and baseline measures of residents' age, gender, behavior, dementia, and serious mental disorders. Follow-up measures in 1993 of residents' age, gender, and serious mental disorders also failed to predict a reduction in use of antipsychotics. However, in nursing homes with a smaller overall proportion of residents with serious mental disorders or alcohol and other drug abuse in 1993, use of antipsychotic drugs was reduced by 50 percent, compared with a reduction of only 26 percent in nursing homes with a larger proportion of residents with serious mental disorders or alcohol and other drug abuse (t=3.31, df=15, p<.05).

Results also showed greater reductions in use of antipsychotic drugs in homes with a high nurse-to-resident staffing ratio at baseline (a reduction of 51 percent versus a reduction of 25 percent; t=4.47, df=15, p<.05) and a high ratio at follow-up (a 57 percent reduction and a 29 percent reduction; t=4.42, df=15, p<.05). Greater reductions in the use of antipsychotic drugs were also found in homes with high nursing leadership stability than in those with low stability (48 percent versus 21 percent; t=4.41, df=15, p<.05). Reductions were also greater in homes with high Medicaid reimbursement at baseline than in those with low reimbursement (51 percent versus 25 percent, t=4.47, df=15, p<.05). Facility ownership and size and reimbursement level at follow-up were unrelated to reductions in the use of antipsychotics.

As predicted, reductions in antipsychotic drug use were significantly greater in facilities with a high score on resident-centered philosophy than in those with a low score (a 50 percent reduction versus a 26 percent reduction; t=3.29, df=15, p<.05), in facilities with a high rating of pharmacist feedback (51 percent versus 22 percent; t=5.78, df=15, p<.05), and in facilities with a high rating of involvement of mental health workers (54 percent versus 26 percent; t=5.31, df=15, p<.05).

To assess the combined effects of a facility's capacity for change and culture, homes were classified into three groups according to baseline capacity and culture scores. At the two facilities with both a low capacity for change and a low rating for resident-centered culture, the use of antipsychotic drugs was reduced by 5.8 percent. In the ten facilities with either a high capacity for change or a high resident-centered culture, the reduction was 30.6 percent. In the four facilities with both a high capacity and a strong resident-centered culture, the reduction was 72.3 percent (F=11.52, df=2, 13, p<.01).

Post-OBRA rates of antipsychotic use were 22.2 percent in facilities with both a low capacity for change and a low rating for resident-centered culture, 18.5 percent in facilities with either a high capacity or a strong resident-centered culture, and 4.9 percent in facilities with both a high capacity and a strong resident-centered culture (F=6.07, df=2, 13, p<.05).

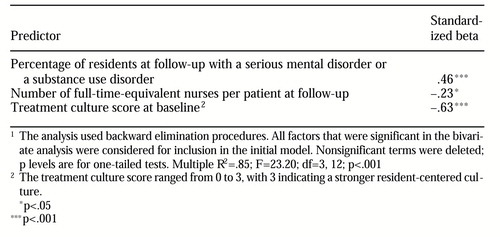

Multiple regression techniques were used to control for possible confounding of organizational measures. All factors that were significant in the bivariate analysis were considered for inclusion in the initial model. Backward elimination procedures were used to delete nonsignificant terms. As shown in Table 3, three factors remained significant. As predicted, use of antipsychotic drugs increased in facilities with a larger proportion of residents with serious mental disorders or alcohol and other drug abuse and decreased in facilities with resident-centered cultures and better staffing. These three factors explained 85 percent of the variance in the nursing homes' response to OBRA's mandate to reduce use of antipsychotic drugs.

Because a pre-post change measure may introduce spurious effects, we repeated the analysis using each facility's pre-OBRA measure of drug use as a covariate and the facility's post-OBRA measure of drug use as the dependent variable. Although coefficients varied slightly, the predictors identified as significant and nonsignificant were similar with the two approaches (data not shown).

Discussion

Our study is the first to document differences in psychotropic drug use related to the treatment cultures of nursing home facilities. It also is the first to quantify the relationship between a facility's treatment culture and its response to drug guidelines in the OBRA legislation. As predicted, greater reductions in the use of antipsychotic drugs were found in facilities with a resident-centered culture that favored individualized assessment and psychosocial care, avoidance of chemical restraints, review and feedback about drug use by pharmacists, and involvement of mental health workers.

Our findings have important policy and practice implications because they identify specific beliefs, norms, communication patterns, and collaborative arrangements that may facilitate change in facilities that have not yet responded to the OBRA mandate. Our findings also raise important questions for sociological research. Why do facilities have such different treatment cultures? Is it possible for a facility to change its treatment culture? How are treatment cultures affected by new regulations, corporate ideologies and policies, professional leadership, and changes in the ways health professionals communicate and collaborate with each other? These questions are virtually unexplored.

Although benzodiazepines were subjected to regulation in 1992, we found little change in their use a year later. Further research is needed to determine why one of every five residents continued to receive benzodiazepines, whether such use was appropriate, and why OBRA apparently succeeded in reducing use of antipsychotic drugs but not use of benzodiazepines. One reason for these mixed results is that enforcement efforts have focused on the excessive use of antipsychotics to manage the behavioral problems of residents with dementia and have devoted little attention to the excessive use of benzodiazepines among depressed but alert residents who often receive these agents as the sole treatment for sleep problems and other symptoms (26).

Our results are consistent with those of past studies; we found a sharp decline in use of antipsychotic drugs, from 24 percent to 15.6 percent, and wide variation in the magnitude of change across facilities. Analysis showed that differences between facilities in the reduction of use of antipsychotics were related to a global measure of mental disorder or substance abuse at follow-up but were unrelated to facility size, facility auspices, residents' demographic characteristics, and baseline rates of dementia and behavioral problems. These findings are consistent with recent findings of a Swedish study demonstrating that residents' characteristics are better predictors of drug use at the individual level than the facility level (18).

The results of bivariate analyses suggested that facilities with higher reimbursement and stable nursing leadership are more responsive to new drug guidelines. We do not know how these factors actually influence a facility's response. One obvious hypothesis is that better funding and leadership produce better nurse staffing, which is essential for improving care. In addition, directors of nursing with longer tenure may acquire the experience or legitimacy needed to identify appropriate tools, mobilize staff, and facilitate communication between nurses and other providers.

Previous studies examining the association of staffing and response to the OBRA regulations have lacked either a measure of drug reduction (9) or information about potential confounders (8). We avoided these problems, and we found a significant association between total nurse staffing and reduction in the use of antipsychotic drugs, even when the analyses controlled for diagnostic mix and treatment culture. This finding is consistent with pre-OBRA studies examining the effects of nurse staffing on drug use (17). It also raises serious concerns about inequities in care, and it reinforces the call for studies to define acceptable staffing standards (27).

Our study had several limitations. The sample of facilities was small, and we cannot generalize our results to other states and populations. It is not known whether the results would have been different if private-pay residents or day-shift nurses had been included. Although we relied on a rich data set, we were not able to reassess nursing home culture after the OBRA regulations were implemented. Studies also are needed to validate our case-mix measures, to evaluate the appropriateness of reductions in drug use, and to determine how these reductions ultimately affected residents' quality of life. Previous research suggests that a reduction in the use of antipsychotic drugs has few, if any, adverse effects on residents (28); however, we did not address this question.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant R01-AG5120 from the National Institute on Aging and grant P50-MH43555 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Svarstad is William S. Apple distinguished professor of social pharmacy and Dr. Mount is associate professor of pharmacy in the social and administrative sciences division of the School of Pharmacy at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, 425 North Charter Street, Madison, Wisconsin 53706 (e-mail, [email protected]). Mr. Bigelow is a researcher at the Center for Health Systems Research in the College of Engineering at the university.

Figure 1. Variation in treatment culture across 16 skilled nursing facilities1

1 Scores on a 12-item medication philosophy scale were standardized and aggregated to create a facility mean that reflected the treatment cultureThe 16 facilities are identified by letters A through P. Facility D scored 0.

Figure 2. Change in the use of antipsychotic drugs at 16 skilled nursing facilities after implementation of regulations in the 1987 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 16 skilled nursing facilities at baseline and follow-up

|

Table 2. Responses to items about treatment culture by 191 nurses in 16 facilities

|

Table 3. Multiple regression analysis of predictors of the percentage change in use of antipsychotic drugs at 16 skilled nursing facilities after implementation of the regulations of the 1987 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act1

1 The analysis used backward elimination proceduresAll factors that were significant in the bivariate analysis were considered for inclusion in the initial model. Nonsignificant terms were deleted; p levels are for one-tailed tests. Multiple R2 =.85; F=23.20; df=3, 12; p<.001

1. Ray WA, Federspiel CF, Schaffner W: A study of antipsychotic drug use in nursing homes: epidemiologic evidence suggesting misuse. American Journal of Public Health 70:485-491, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Beers M, Avorn J, Soumerai S, et al: Psychoactive medication use in intermediate-care facility residents. JAMA 260:3016-3020, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Kane RL, Williams CC, Williams TF, et al: Restraining restraints: changes in a standard of care. Annual Review of Public Health 14:545-584, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Medicaid State Operations Manual: Provider Certification, Transmittal 232. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Care Financing Administration, Sept 1989Google Scholar

5. Medicaid State Operations Manual: Provider Certification, Transmittal 250. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Care Financing Administration, Apr 1992Google Scholar

6. Ray WA, Griffin MR, Schaffner W, et al: Psychotropic drug use and the risk of hip fracture. New England Journal of Medicine 316:363-369, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Rovner BW, Edelman GA, Cox MP, et al: The impact of antipsychotic drug regulations on psychotropic drug prescribing practices in nursing homes. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:1390-1392, 1992Link, Google Scholar

8. Shorr RI, Fought RL, Ray WA: Changes in antipsychotic drug use in nursing homes during implementation of the OBRA-87 regulations. JAMA 271:358-363, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Garrard J, Chen V, Dowd B: The impact of the 1987 federal regulations on the use of psychotropic drugs in Minnesota nursing homes. American Journal of Public Health 85:771-776, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Borson S, Doane K: The impact of OBRA-87 on psychotropic drug prescribing in skilled nursing facilities. Psychiatric Services 48:1289-1296, 1997Link, Google Scholar

11. Castle NG: Deficiency citations for physical restraint use in nursing homes. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences 55B:S33-S40, 2000Google Scholar

12. Castle N, Banaszak-Holt J: Top management team characteristics and innovation in nursing homes. Gerontologist 37:572-580, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Rovner BW, Steele CD, Shmuely Y, et al: A randomized trial of dementia care in nursing homes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 44:7-13, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Silverman M, McAllister C: Continuities and discontinuities in the life course: experiences of demented persons in a residential Alzheimer's facility, in The Culture of Long Term Care: Nursing Home Ethnography. Edited by Henderson JN, Vesperi MD. Westport, Conn, Gergin and Garvey, 1995Google Scholar

15. McLean A, Perkinson M: The head nurse as key informant: how beliefs and institutional pressures can structure dementia care, in ibidGoogle Scholar

16. Hawes C, Phillips CD: The changing structure of the nursing home industry and the impact of ownership on quality, cost, and access, in For-Profit Enterprise in Health Care. Edited by Gray BS. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1986Google Scholar

17. Svarstad BL, Mount JK: Nursing home resources and tranquilizer use among the institutionalized elderly. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 39:869-875, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Schmidt I, Claesson C, Westerholm B, et al: Resident and organizational factors affecting the quality of drug use in Swedish nursing homes. Social Science and Medicine 47:961-971, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Rogers EM: Diffusion of Innovations, 4th ed. New York, Free Press, 1995Google Scholar

20. Shortell SM, O'Brien JL, Carman JM, et al: Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement/total quality management: concept versus implementation. Health Services Research 30:377-401, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

21. Martin J: Cultures in Organizations: Three Perspectives. New York, Oxford University Press, 1992Google Scholar

22. Bashaw M, Adams M: Nursing home nurses' attitudes, empathy, and ideologic orientation. International Journal of Aging and Human Development 22:235-246, 1985-1986Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Mount JM: Nursing home responsiveness to research requests: results of a field study. Gerontologist 32:414-419, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Ray WA, Griffin MR: Use of Medicaid data for pharmacoepidemiology. American Journal of Epidemiology 129:837-849, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Svarstad BL: Sleep Medication Use in Skilled Nursing Facilities: Effects of Nurse Beliefs and Norms. University of Wisconsin Mental Health Research Center, Research Paper Series 21:1-18, July 1992Google Scholar

26. Heston LL, Garrard J, Makris L, et al: Inadequate treatment of depressed nursing home elderly. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 40:1117-1122, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Harrington C, Carrillo, Mullan J, et al: Nursing facility staffing in the states: the 1991-1995 period. Medical Care Research and Review 55:334-363, 1998.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Thapa PB, Meador KG, Gideon P, et al: Effects of antipsychotic withdrawal in elderly nursing home residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 42:280-286, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar