The ICCD Benchmarks for Clubhouses: A Practical Approach to Quality Improvement in Psychiatric Rehabilitation

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study evaluated whether the average performance of clubhouses certified by the International Center for Clubhouse Development (ICCD) should be considered valid benchmarks for clubhouse programs. METHODS: A representative sample of clubhouses more than three years old that were based on the Fountain House model participated in a 1998 mail survey. To verify that ICCD certification is a valid indicator of program quality for use in setting benchmark performance rates, 71 certified and 48 noncertified programs were compared on a variety of organizational variables. RESULTS: Even though certified and noncertified clubhouses were similar in organizational structure and resources, findings from a logistic regression analysis confirmed that certified clubhouses provided a wider array of rehabilitation services and achieved higher rates of employment. CONCLUSIONS: The findings suggest that ICCD certification is a valid indicator of program quality. The ICCD has therefore proposed that the average performance of certified U.S. clubhouses in specific domains be adopted as benchmarks for organizational performance. When tailored for programs in particular regions and with specific levels of funding, the ICCD benchmarks for clubhouse performance set fair and reasonable expectations for clubhouse programs and for the design of performance contracts between departments of mental health and ICCD clubhouses.

The clubhouse model of psychiatric rehabilitation originated in 1948 at Fountain House in Manhattan (1). Fountain House was founded by former hospital patients as a collaborative community composed of both professional staff and people with serious mental illness (2,3). The primary community activity is the work-ordered day, in which members and staff work side-by-side to run the program (4). Although the work-ordered day is the heart of a clubhouse (5), it is meant to be a catalyst for member recovery rather than a full-time activity. Clubhouse members are helped to find mainstream employment and educational resources outside the clubhouse. In addition, social work services and supported housing services further integrate members into the wider community. The goal of every clubhouse is to help members lead fulfilling lives, and a deep respect is maintained for the individual nature of this journey (6).

In 1976 a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health allowed Fountain House to provide training in the clubhouse model throughout the United States. In 1988 this training program became the national clubhouse expansion program, funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Pew Charitable Trusts, and the Public Welfare Foundation. The program evolved into the International Center for Clubhouse Development, Inc. (ICCD) in 1994. The ICCD now has ten training bases offering a common three-week training curriculum. All ICCD training and consultation is grounded in the Standards for Clubhouse Programs (7), which are reviewed, augmented if necessary, and reapproved every two years by clubhouse representatives at the ICCD international seminar.

In 1994 the ICCD began to assign certification status on the basis of detailed self-studies, three-day site visits, and reviews of site records. Certification assessments are conducted by trained members and staff from well-established clubhouses (8). ICCD certification serves as a quality assurance procedure (9,10) that documents the extent to which mandated services are provided in a specified manner.

Because certification is useful for monitoring performance, the states of Utah and Massachusetts immediately incorporated ICCD certification into their performance contracts with clubhouse programs (11). However, state authorities still had to provide programs with clear performance expectations. The ICCD was asked to set benchmark performance rates to serve both as guidelines for program development and as standards against which the outcomes of any individual clubhouse could be compared. ICCD clubhouse benchmarks were intended to allow the evaluation of program performance relative to a normative sample of certified clubhouses and to aid mental health authorities in the design of clubhouse performance contracts.

This paper describes the ICCD's development of benchmark performance rates for clubhouse programs. To test the utility of these benchmark rates as quality assurance standards, we first posed a research question: Are currently ICCD-certified clubhouses a valid reference group for setting benchmark figures? That is, is the average performance of ICCD-certified clubhouses reflective of overall high quality? To answer this question, we compared certified and noncertified clubhouses on several variables, including outcomes typically addressed by performance contracts, such as hours of operation and employment rates among members.

Methods

The ICCD conducts surveys every two years to monitor the progress of certification and training. The study reported here was based on responses to the 1998 clubhouse survey, which targeted 170 U.S. clubhouses listed in the 1996 ICCD clubhouse directory. All but seven of these targeted programs (N=163) fit the requirements for the study reported here—that is, they were professionally staffed mental health clubhouses with more than 15 and fewer than 500 active members.

Content of the survey

To ensure comparability in reporting procedures, operational definitions and calculation formulas were provided in the questionnaire. Paid work by members was classified as independent or supported employment, transitional employment, or noncompetitive work. Because the terms "independent" and "supported" are used interchangeably by many clubhouses, these two types of work were grouped together. In keeping with the Standards for Clubhouse Programs, the definitions for independent, supported, and transitional employment all fit the federal definition for competitive employment (12,13). All such jobs pay at least minimum wage and are located in integrated mainstream settings. Types of competitive work differed primarily in the level of support, with independent jobs requiring the least amount of support and transitional jobs the greatest.

Definitions of other concepts were based on findings from interim surveys conducted by the ICCD to identify the reporting time frames and operational definitions most commonly used by state and regional mental health authorities. For example, active membership was defined as the total number of members who had any face-to-face contact with clubhouse staff during a three-month period. Time frames for reporting were each agency's most recent fiscal year for monetary figures and any three-month period within this fiscal year for attendance and employment figures.

The survey sample

A total of 128 of the targeted clubhouses responded to the 1998 survey, with a 95 percent response rate for certified clubhouses and a 48 percent response rate for noncertified clubhouses. Omitted from the study sample were nine responding clubhouses—three certified and six noncertified—that had been in operation less than three years. The omission of these relatively young clubhouses was in keeping with the study's intent to report performance rates for established programs. The final survey sample of 119 clubhouses consisted of 71 certified clubhouses located in 24 states and 48 noncertified clubhouses in 22 states. The most frequent respondents were the clubhouse director (86 percent) or assistant director (7 percent).

Because the response rate for noncertified clubhouses was much lower than that for certified clubhouses, a check was made on the representativeness of the 1998 sample of noncertified programs. We compared the 36 noncertified clubhouses in the 1996 survey that responded to the 1998 survey to the 50 clubhouses that did not respond. Noncertified clubhouses responding to the 1998 survey provided more employment in 1995 and 1996 than the nonresponding clubhouses (t=2.47, df=41.49, p<.05). Respondents and nonrespondents were highly similar on 20 other key variables, including clubhouse age, budget, total number of active members, staffing, operating hours, and total number of members employed, suggesting that the 48 noncertified clubhouses in the 1998 survey constituted a representative sample of programs without ICCD certification that use the label "clubhouse." Two-thirds of the 48 noncertified clubhouses reported that they intended to seek ICCD certification in the future. In almost all instances, the reasons given for not seeking certification were restrictions on operations mandated by auspice agencies or funding sources that prevented full compliance with ICCD standards. Only one clubhouse had applied for certification and failed an assessment.

Results

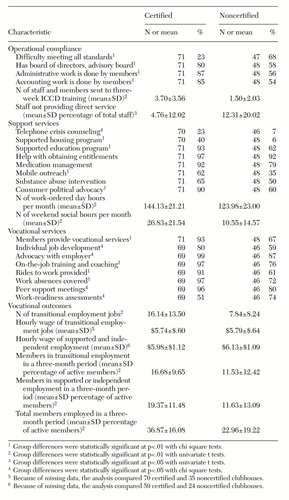

Validity of ICCD certification

Certified versus noncertified clubhouse performance. As Tables 1 and 2 show, certified and noncertified clubhouses were comparable in organizational resource characteristics, but they differed substantially in performance. Certified clubhouses performed significantly better (p<.05) than noncertified clubhouses on 25 of the 30 performance indicators in Table 1. All group differences indicated greater compliance with the Standards for Clubhouse Programs by certified clubhouses. For instance, a larger proportion of certified clubhouses provided job development and on-the-job support, but a larger proportion of noncertified clubhouses provided work-readiness assessments. ICCD clubhouses are mandated to provide comprehensive supported employment services, but the Standards oppose the use of work-readiness assessments. Certified clubhouses substantially outperformed noncertified clubhouses in terms of employment. Nearly twice as many members of certified clubhouses worked transitional and supported or independent employment jobs.

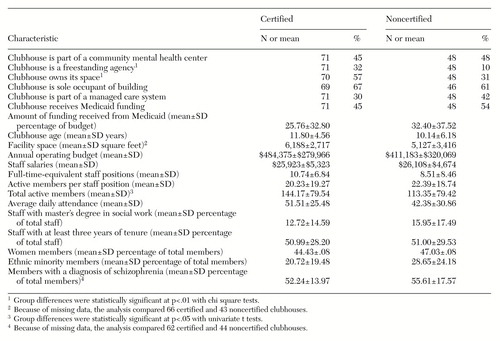

Even though the certified clubhouses showed superior performance, no group differences were found in organizational resource variables that could have influenced performance. Certified and noncertified clubhouses differed significantly on only three of the 20 resource variables presented in Table 2. Although certified and noncertified clubhouses had comparable budgets and staff-to-member ratios, certified clubhouses served more members during a typical three-month period. Also, a greater proportion of certified clubhouses were freestanding, and thus were more likely than noncertified clubhouses to own their facility.

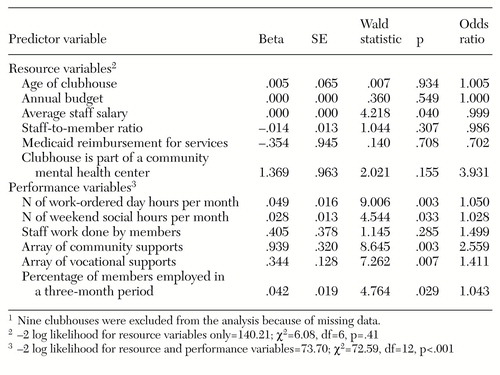

Predictors of certification status. A logistic regression analysis examined whether organizational performance predicted ICCD certification status when variations in program resources were taken into account. To reduce collinearity, representative measures were selected from within sets of highly correlated variables in the 1998 survey. Six organizational resource variables were entered simultaneously into the analysis as a first block of control covariates: clubhouse age, annual budget, mean staff salary, staff-to-member ratio, whether or not funding was received from Medicaid, and whether or not the program was part of a mental health center.

This block of resource variables was followed by a second block of six performance variables highly representative of the criteria used for determining clubhouse certification. Two variables measuring hours of operation—work-ordered day and number of hours of social programming—were taken directly from survey reports. The percentage of members employed in a three-month period was calculated as a ratio of total members employed to total active members. Three other variables, staff work done by members, array of community supports, and array of vocational supports, were composite variables created by summing dichotomous (checklist) items.

The results of the logistic regression analysis are presented in Table 3. The six resource variables included as the first block were not as a group predictive of certification status. The group of six performance variables significantly predicted certification status when the analysis controlled for the organizational resource variables. Five of the six performance measures were significant predictors of certification status.

When the analysis controlled for basic resources, a clubhouse was more likely to be certified if it provided a wider array of services and helped more members obtain employment. The full logistic regression model containing both resource and performance variables was statistically significant and correctly predicted the certification status of 85 percent of the clubhouses in the sample.

The 12 variables correctly classified all but seven certified and ten noncertified clubhouses out of a total of 110 programs in the analysis. These results support the validity of using ICCD certification as a quality assessment tool and of basing benchmark figures on the superior performance of U.S. certified clubhouses.

Benchmark performance rates

Calculation of the benchmark performance rates. Benchmark performance rates were derived from the responses of U.S. certified clubhouses to the 1998 ICCD clubhouse survey. The mean was selected as the basic benchmark figure for most tables because ICCD clubhouses reported greater familiarity with this statistic. However, mean scores were close in value to midpoint (median) scores for nearly every survey variable. That is, the ICCD benchmark figures represent levels of performance that have been attained by approximately half of all certified clubhouses in the United States.

Benchmark performance rates were calculated as actual counts rather than percentages or ratios to ensure that the figures would hold real-world meaning for all stakeholders. However, ratios and percentages can be easily calculated. For instance, to compute the mean percentage of active members employed, the number of members employed can be divided by the total number of active members. Tables with percentages and ratios as well as tables with standard deviations and median statistics are available from the ICCD.

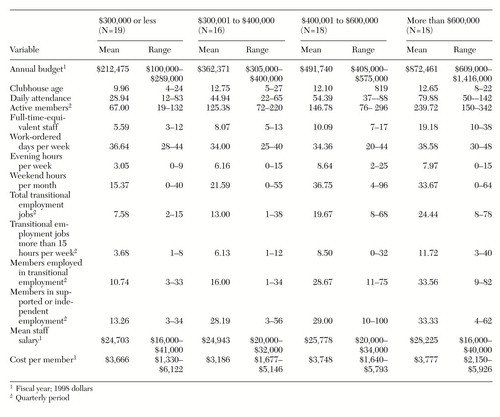

Construction of the ICCD benchmark performance tables. Because the demands and constraints imposed by governments as well as by local economic and environmental factors influence a clubhouse's ability to perform well, benchmark rates were calculated separately for clubhouses in different locations, of different ages, and with different levels of funding. Location was defined as rural, urban, or metropolitan according to the urban influence codes provided by the economic research service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (14). Clubhouse age was dichotomized as less or more than ten years of operation. Funding was defined as total operating budget for the 1998 fiscal year, minus costs for substantial auxiliary programs such as supported housing or mobile outreach teams. Annual budgets were grouped as $300,000 or less, $300,001 to $400,000, $400,001 to $600,000, and more than $600,000.

Statistical tests revealed no significant differences in benchmark figures between clubhouses with different ages, locations, and budget categories when performance was expressed as a ratio or percentage. When benchmarks were expressed as actual counts, statistically significant differences were found only across budget categories. As would be expected, clubhouses with larger budgets had higher performance. For instance, clubhouses with larger budgets had more members and more members employed.

A strong relationship between budget and location was also noted, primarily because of a high proportion of rural clubhouses with budgets under $300,000 (χ2=22.37, df=6, p= .001; N=71). In general, clubhouses with larger budgets tended to be in urban or metropolitan locations rather than rural locations. Urban programs tended to have more staff, to provide a wider array of services, and to serve more clients. For this reason, rural clubhouses had fewer employed members, even though the percentage of members employed was equivalent across locations.

A positive correlation was also found between annual operating budget and clubhouse age, with older clubhouses having larger budgets. However, this correlation was statistically significant only for clubhouses that had been in operation for less than ten years (r=.44, p<.05; N=26).

All ICCD clubhouses are provided with benchmark tables cross-indexed by location, annual budget, and organizational age to allow a comparison of their own performance with that of certified clubhouses of similar age in similar locations with similar levels of funding. Likewise, state-specific benchmark tables are available for states that have ten or more certified clubhouse programs. Researchers and policymakers are advised to use national tables based on only budget categories, age categories, or location categories so that average figures and calculated ratios are derived from larger samples. Table 4 presents the benchmark rates for ICCD-certified U.S. clubhouses in specific budget categories.

Regardless of which table is used, one can judge the appropriateness of a specific benchmark figure by examining minimum and maximum scores. If the range of scores is small, a clubhouse is strongly expected to meet or exceed the average score. If a range is large, more latitude can be taken in setting performance expectations.

Discussion

The 1998 survey findings demonstrate that ICCD certification provides a generally valid assessment of program quality. The performance of certified clubhouses was superior to that of noncertified clubhouses even when statistical analyses controlled for variations in basic organizational resources and when all programs in the study publicly accepted the basic tenets of the model. For this reason, the performance of ICCD-certified clubhouses can be used to benchmark good organizational performance for all programs that are similar to the clubhouse model in operation and purpose.

Relying on ICCD-certified clubhouses as a reference group for setting performance benchmarks also provides a large research sample for the study of fiscal and policy constraints on mental health service delivery in the United States. On the one hand, comparability in certified clubhouse performance ratios across location, funding, and age categories suggests that benchmark performance can be achieved by nearly any program adhering to the Standards for Clubhouse Programs regardless of external constraints, as long as the program is over three years of age and has an annual budget of at least $100,000. On the other hand, the fact that most noncertified clubhouses reported that external constraints prevented their compliance with the Standards for Clubhouse Programs signals a need for further study. If such operational restrictions are based on assumptions related to performance, it is essential to reexamine these assumptions in light of the benchmark performance of certified clubhouse programs.

Benchmarking the performance of any service model also offers an opportunity to disseminate model-specific guidelines about what types of services should be provided. Choice of variables to be benchmarked clearly indicates what services are critical to the model. For instance, the ICCD benchmarks include employment rates for supported or independent employment in addition to rates for transitional employment, with the overall rate of competitive employment averaging 37 percent over a three-month period. The benchmarks show that the rates of supported and independent employment for certified clubhouses are equivalent to their rates for transitional employment, even though clubhouses tend to be characterized as primarily providing transitional employment. It is also important to note that all employment rates were calculated as percentages of total active members, many of whom may have been unavailable or may have had no interest in paid work at the time they enrolled in the clubhouse (15). The inclusion of all members in the calculation of the employment ratios sends a clear message to clubhouses that mainstream employment should be a primary organizational objective, continuously available to every member regardless of initial impressions of individual receptivity or work-readiness.

The study had some limitations. Reliance on the reports of clubhouse directors for validating ICCD certification raises the issue of data reliability. It is possible that survey respondents exaggerated or fabricated the figures reported on the questionnaires. However, because the performance of ICCD-certified clubhouses is closely monitored during certification visits through direct observation, record reviews, interviews, and job-site visits to employed members, any bias in self-reported information was likely to be in favor of the noncertified clubhouses, whose performance the ICCD has no way of verifying. Likewise, the lower response rate for noncertified clubhouses to the 1998 survey poses minimal bias. The survey required public identification with the clubhouse model and organizational accountability in reporting detailed attendance, fiscal, and employment information, so programs with limited resources or poor outcomes were least likely to respond.

Benchmarking will be repeated by the ICCD on a biannual basis as a method for continuous quality improvement (16,17). Whenever certified clubhouse performance in specific domains reflects a need for focused consultation and training, the ICCD will inform its community of clubhouses. Alternatively, when the average performance of certified clubhouses rises, benchmark rates will be readjusted to reflect higher expectations for performance. High stability in ICCD clubhouse survey responses over the past decade suggests that two-year updates will be sufficient to keep pace with regional or national changes that influence performance.

The ICCD benchmark performance rates, and the method for their development, represent a prototype for setting performance expectations that could be followed by any coalition or association of programs. Just as randomized, controlled studies demonstrate the efficacy of a model to achieve certain levels of performance, benchmark performance rates demonstrate the generalizability of such experimental findings. In the case of the ICCD clubhouse model, knowing that a large number of existing programs have already reached performance standards comparable with the published outcomes of an experimental program (15) strengthens policymakers' confidence in the replicability of well-defined service models and the diffusion of best-practice strategies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Charles Rodican, M.S.W., who ensured that the survey was conducted as side-by-side work within the Fountain House work-ordered day. They also thank Rudyard Propst, Joel Corcoran, M.S.W., Matthew Johnsen, Ph.D., and Kenneth Dudek, M.S.W., for their thoughtful reading of the manuscript. The preparation of this article was supported by a grant from the van Ameringen Foundation to Fountain House, Inc., and through a gift from Nicholas and Llewellyn Nicholas.

Dr. Macias is affiliated with Fountain House, Inc., 425 West 47th Street, New York, New York 10036 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Barreira was previously affiliated with the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health and is now with McLean Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Dr. Alden is affiliated with the Utah Department of Mental Health in Salt Lake City. Mr. Boyd is with Fordham University in New York City.

|

Table 1. Organizational performance characteristics of 71 clubhouses certified by the International Center for Clubhouse Development (ICCD) and 48 noncertified clubhouses

|

Table 2. Organizational resource characteristics of 71 clubhouses certified by the International Center for Clubhouse Development (ICCD) and 48 noncertified clubhouses

|

Table 3. Logistic regression analysis of variables predicting clubhouse certification status among 110 certified and noncertified clubhouses1

1 Nine clubhouses were excluded from the analysis because of missing data

|

Table 4. Benchmark performance rates for certified clubhouses by level of annual funding

1. Anderson SB: We Are Not Alone: Fountain House and the Development of Clubhouse Culture. New York, Fountain House, 1998Google Scholar

2. Beard JH: The rehabilitation services of Fountain House, in Alternatives to Mental Hospital Treatment. Edited by Stein L, Test MA. New York, Plenum, 1978Google Scholar

3. Beard JH, Propst R, Malamud T: The Fountain House model of psychiatric rehabilitation. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 5:47-53, 1982Google Scholar

4. Macias C, Jackson R, Schroeder C, et al: What is a clubhouse? Report on the 1996 survey of USA clubhouses. Community Mental Health Journal 35:181-190, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Waters B: The work unit: heart of the clubhouse. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 16:41-48, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Macias C, Rodican C: Coping with recurrent loss in mental illness: unique aspects of clubhouse communities. Journal of Personal and Interpersonal Loss 2:205-221, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Propst R: The standards for clubhouse programs: why and how they were developed. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 16:25-30, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Propst R: Stages in realizing the international diffusion of a single way of working: the clubhouse model. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 74:53-66, 1997Google Scholar

9. Smukler M, Sherman P, Srebnik DS, et al: Developing local service standards for managed mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 24:101-116, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Martin LL, Kettner PM: Performance measurement: the new accountability. Administration in Social Work 21:17-29, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Macias C, Harding C, Alden M, et al: The value of program certification for performance contracting: the example of ICCD clubhouse certification. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 26:345-360, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Department of Labor: Job Training Program Act, Disability Grant Program Funded Under Title III, Section 323, and Title IV, Part D, Section 452. Federal Register 63:15216-15227, 1998Google Scholar

13. Workforce Investment Act of 1998. PL 105-220, Aug 7, 1998Google Scholar

14. Ghelfi LM, Parker TS: A county-level measure of urban influence. ERS staff paper 9702. Washington, DC, US Department of Agriculture, Rural Economy Division, Economic Research Service, 1997Google Scholar

15. Macias C, DeCarlo L, Wang Q, et al: Work interest as a predictor of if, when, and how long someone will work: policy implications for the field of psychiatric rehabilitation. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, in pressGoogle Scholar

16. Deming WE: Out of Crisis. Cambridge, Mass, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1986Google Scholar

17. Chowanec GD: Continuous quality improvement: conceptual foundations and application to mental health care. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:789-793, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar