Treatment of Acute Schizophrenia in Open General Medical Wards in Jamaica

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study assessed the efficacy of treating acute psychotic illness in open medical wards of general hospitals. METHODS: The sample consisted of 120 patients with schizophrenia whose first contact with a psychiatric service in Jamaica was in 1992 and who were treated as inpatients during the acute phase of their illness. Based on the geographic catchment area where they lived, patients were admitted to open medical wards in general hospitals, to psychiatric units in general hospitals, or to acute care wards in a custodial mental hospital. At first contact, patients' severity of illness was assessed, and sociodemographic variables, pathways to care, and legal status were determined. At discharge and for the subsequent 12 months, patients' outcomes were assessed by blinded observers using variables that included relapse, length of stay, employment status after discharge, and clinical status. RESULTS: More than half (53 percent) of the patients were admitted to the mental hospital, 28 percent to general hospital medical wards, and 19 percent to psychiatric units in general hospitals. The three groups did not differ significantly in geographic incidence rates, patterns of symptoms, and severity of psychosis. The mean length of stay was 90.9 days for patients in the mental hospital, 27.9 days in the general hospital psychiatric units, and 17.3 days in the general hospital medical wards. Clinical outcome variables were significantly better for patients treated in the general hospital medical wards than for those treated in the mental hospital, as were outpatient compliance and gainful employment. CONCLUSIONS: While allowing for possible differences in the three patient groups and the clinical settings, it appears that treatment in general hospital medical wards results in outcome that is at least equivalent to, and for some patients superior to, the outcome of treatment in conventional psychiatric facilities.

As a result of developments in psychopharmacology and the community psychiatry movement, community treatment units have replaced the mental hospital ward as the main setting for treating patients with acute mental illness. These changes have occurred internationally, but in many developing countries economics and other factors have forced some modifications. In Jamaica, admission of acutely ill psychiatric patients to open medical wards of general hospitals became standard practice in 1970 (1,2,3,4,5), when hospital admissions were restricted to the geographic catchment area where the patient lived. Within each catchment area, patients had to go where beds were available, and by 1990 nearly 50 percent of all acute psychiatric admissions in the country were to open medical wards.

This study tested the efficacy of treating acute psychotic illness in open medical wards of general hospitals in Jamaica. The issue is especially pertinent in the context of the worldwide discussion about the increasing demand for more beds for acutely ill psychiatric patients.

Methods

We followed a cohort of patients with schizophrenia in three catchment areas who were first identified in 1992 (6). The outcome of patients admitted to the open medical wards of five rural general hospitals was compared with the outcome of patients treated in two other types of inpatient settings: the acute care wards of the island's single mental hospital, in Kingston, and the two psychiatric units in general hospitals—called community psychiatric units—in Kingston and Montego Bay. Outcome evaluations were made at discharge and for the subsequent 12 months by observers blind to whether patients were study participants.

The facilities

The island's single mental hospital is Bellevue Mental Hospital in Kingston. Its three acute care wards of 50 beds each serve a designated geographic catchment area of the contiguous parishes of Kingston, St. Andrew, and St. Catherine, a population that is 70 percent urban (7). The mental hospital's geographic catchment area is only slightly smaller than the other catchment areas combined.

The community psychiatric units, which consist of 20 to 45 acute care beds, are located at the University Hospital of the West Indies in Kingston and at Cornwall Regional Hospital in Montego Bay. University Hospital's catchment area is the parish of St. Andrew, with a population that is 90 percent urban (7). Cornwall Hospital's catchment area consists of the parishes of St. James and Hanover, where 75 percent of the population is rural (7).

The open medical wards are located in five parish hospitals in Trelawny, Westmoreland, St. Elizabeth, Manchester, and Clarendon. These hospitals have medical, surgical, and obstetric and gynecological wards of 40 beds each. They serve catchment areas in which 85 percent of the population is rural (7). Rarely are more than three to five acutely mentally ill patients on the open medical wards of the general hospitals at any one time.

A medical consultant, a junior medical officer, a mental health officer, and a cadre of registered and enrolled nurses staff all three types of facilities. A psychiatrist is available on a part-time basis. In each facility, a multidisciplinary team provides eclectic psychiatric treatment that includes clinical assessment, psychopharmacology, individual and group psychotherapy, and family therapy.

In all three types of facilities, staff-patient ratios are about the same, and the type and quantity of psychopharmacological treatment is similar. Involuntary patients on general medical wards are most often subdued, when necessary, by sedation and rapid neuroleptization, although arm and leg restraints may be used in the acute phase of illness.

Case selection and sampling

As noted, admission to the three types of facilities was determined strictly by geographic catchment area. Patients came to the catchment-area hospital by self-referral or were brought by relatives, the police, or mental health officers. The latter are equivalent to community psychiatric nurses with additional autonomy and clinical responsibility for assessment and follow-up care. Hospital admission was predicated on the capacity of the patient's family to manage and cope with disturbed behavior at home.

Inclusion criteria for the study were those used by the World Health Organization's determinants-of-outcome study (8). That is, patients were between 15 and 54 years old, had lived in the area for at least six months, had shown at least one overt symptom or at least two abnormalities suggestive of a psychotic illness, and had recently made a first-time contact with a helping agent.

Assessment and clinical follow-up

Diagnoses were made using a standardized diagnostic instrument, the Present State Examination (PSE) (9). Only patients receiving a CATEGO diagnosis of schizophrenia were admitted to the study. The CATEGO, the computer diagnostic program for the PSE (9), applies defined algorithms to interview data; it is the United Kingdom equivalent of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (10).

Sociodemographic variables, pathways to care, and legal status were identified and recorded at the time of the patient's first contact with the facility. Krawiecka and associates' scale (11) was used to measure the severity of positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. At the time of discharge from the hospital, each patient was seen in the outpatient clinic by the psychiatrist or by the mental health officer, who was blind to whether patients were included in the study. The patients were assessed at each visit for 12 months after discharge for the presence of clinical symptoms, employment status, and level of compliance with medication. Accompanying relatives were also interviewed about the patient's clinical state and level of general behavior.

Outcome variables

The outcome variables used were those identified by Birchwood and colleagues (12), and data on them were collected in a manner similar to that described by Birchwood's group. Two mental health officers examined the case notes of each patient in the cohort for evidence of relapse during the calendar year after discharge from the hospital. Outcome data for patients whose case notes could not be found were obtained through home visits by the mental health officer.

Psychotic relapse was defined as admission or readmission to the hospital, reemergence of hallucinations or delusions, or the return of abnormal behavior. The number of times patients were in contact with the community psychiatric service and, if contact was not continued, the reason for cessation of contact were also recorded. Besides relapse, outcome variables included continuous hospitalization, absconding from the hospital without discharge, and length of hospital stay. The criterion for satisfactory outpatient treatment compliance was attendance at more than three scheduled clinic appointments in the 12-month period following discharge. Poor clinical outcome was determined by a combination of factors—clinical relapse, continuous hospitalization after admission, and absconding from the hospital without discharge.

All data were entered into a computer and statistical analysis used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for equality of variance, the t test for equality of means, and the chi square test of association between variables.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Of the cohort of 317 patients who were identified as suffering from schizophrenia and who had made first contact with the psychiatric service in 1992, a total of 120 (38 percent) were admitted to a hospital for the treatment of their acute psychosis. More than half of the patients (64, or 53 percent) had been admitted to the mental hospital, 33 (28 percent) to open medical wards in general hospitals, and 23 (19 percent) to community psychiatric units.

Nearly all patients (118, or 98 percent) were of African descent, and two (2 percent) were of East Indian descent. All were born and raised in Jamaica. No significant differences were found in the social class of the treatment groups.

Seventy-three (61 percent) of the patients were males, and 47 (39 percent) were females, in keeping with the significant preponderance of males over females in the original study cohort (6). However, males and females were equally distributed in the three types of treatment facilities, and no significant difference in employment status was found by gender.

Homogeneity of the subsamples

In 1992 the total number of first-contact patients with schizophrenia per 100,000 population was 1.15 for the mental hospital catchment area, 1.5 for the catchment areas with the community psychiatry units, and 1.4 for the catchment areas with the general medical wards. The differences were not significant. Of the patients admitted to the mental hospital, 83 percent (N=53) were from the designated catchment area, as were 86 percent (N=19) of the admissions to the community psychiatric units and 90 percent (N=30) of the admissions to the general medical wards. Again the differences were not significant. Thus the degree of "leakage" in admissions from one geographic area to another was similar among the three types of facilities.

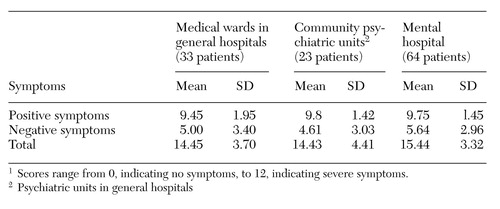

Table 1 shows total mean scores and mean scores for positive and negative symptoms on Krawiecka and associates' scale (11). No significant differences were found between patients in the three types of inpatient facilities using one-way ANOVA, suggesting that the three admission samples had similar patterns of clinical symptoms and severity of psychosis.

Length of hospital stay

The mean±SD length of stay for the 64 patients admitted to Bellevue Mental Hospital was 90.88±87.96 days, compared with 27.91±25.37 days for the 23 patients admitted to the community psychiatric units and 17.30±15.22 days for the 33 patients admitted to the general medical wards. Comparisons of length of stay in the three types of inpatient facilities found statistically significant differences between the general medical wards and the mental hospital (t=−3.37, df=85, p<.001), between the mental hospital and the community psychiatric units (t=−4.76, df=95, p<.001), and between the general medical wards and the community psychiatric units (t=−1.95, df=54, p<.05).

Outcomes and clinical status 12 months after discharge

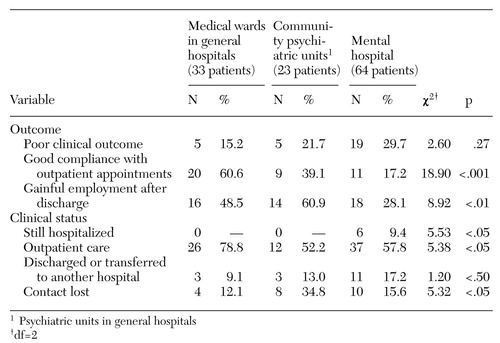

Table 2 compares outcomes 12 months after discharge among patients admitted to the three types of inpatient facilities as measured by poor clinical outcome, good compliance with outpatient appointments, and gainful employment after discharge. A statistically significant difference was found between the three types of facilities for all three variables (χ2=12.51, df=4, p<.02). A higher percentage of patients admitted to the mental hospital had poor clinical outcomes compared with those admitted to the general medical wards (χ2=6.50, df=1, p<.01); however, no significant differences in clinical outcomes were found between patients admitted to community psychiatric units and the mental hospital or between admissions to the general medical wards and the community psychiatric units.

A smaller proportion of patients admitted to the mental hospital were employed after 12 months compared with the patients admitted to the other two types of facilities (χ2=8.92, df=2, p<.01). Fifty-five of the urban patients (63 percent) and 17 of the rural patients (51 percent) were employed after 12 months, a nonsignificant difference.

A statistically significant difference in the clinical status of patients admitted to the three types of facilities was found 12 months after discharge on four variables: still hospitalized, in outpatient care, discharged or transferred to another hospital, or lost contact (χ2=12.65, df=6, p<.05). Patients admitted to the open general medical wards consistently did better than those at the other two types of facilities.

Discussion

Little published work has compared the nature of inpatient psychiatric facilities and patients' outcome. The main findings of this study were that patients admitted to open general medical wards had significantly shorter lengths of hospital stay and a superior one-year outcome compared with patients admitted to conventional community psychiatric units or patients treated in acute wards of mental hospitals. The medical ward patients also exhibited greater compliance with outpatient appointments, and significantly more were gainfully employed after discharge.

Studies in the psychiatric literature of the relationship of length of stay to outcome suggest that excessive length of stay might be associated with poorer follow-up indicators, even when admissions are randomized (13). The findings of this study support that suggestion. However, because the staff-patient ratio and the quality of medication management in each of the three facilities were about equal, it is likely that the type of therapeutic facility determines length of stay.

This study raises many important methodological issues. The key question is whether the results reflect the nature of the treatment received in the different units or whether they reflect the nature of the underlying illness that resulted in the patient's being admitted to that unit. Some observers suggest that an urban environment is more schizophrenogenic than a rural environment (14). If that were so, patients from predominantly rural areas who were admitted to the general medical wards would be expected to have a better outcome. Our findings suggest, however, that the incidence rate for first-contact schizophrenia in the rural areas of Jamaica is not significantly different from in the urban areas. Furthermore, the data on social class suggest that social and economic support factors are not significantly different for the rural or urban study catchment areas. In addition, recent studies suggest that, unlike the situation in the United Kingdom and other metropolitan countries, more than 60 percent of the poorest people in Jamaica live in rural areas (15).

Because the number of admissions from outside the catchment area did not differ significantly among the three types of facilities, it cannot be suggested that more severely ill patients were admitted to one type of facility, such as the mental hospital, than another. The similarity of the positive and negative symptom scores and the overall total scores on Krawiecka and associates' scale for admissions to all three types of facilities also suggests that admission to a particular facility was not driven by a difference in symptom profile or the severity of the illness. Thus improvement in the outcome variables is likely to reflect the efficacy of the type of inpatient facility rather than the nature of the underlying illness.

It is possible that the superior outcome for patients admitted to open general medical wards may be due to the use of more aggressive treatment practices in response to the demand for space and less tolerance of disturbed behavior. Hospital facilities across the island have relatively uniform nursing and medical staffing patterns. Hence it is unlikely that larger or better medical and nursing staffs in some facilities have skewed the findings of this study. Improvement in the outcome variables reported is likely to reflect the efficacy of the general medical ward rather than the nature of the underlying illness.

The question of selection bias must also be considered. Would there have been similar findings had all psychiatric admissions or all patients diagnosed as suffering from schizophrenia been studied rather than just first-contact patients? Since the early 1990s, admissions to each of these facilities have been limited strictly by geographic catchment area. Therefore, the frameworks from which the sample was drawn can be assumed to be similar.

The preponderance of males over females in the inpatient sample may suggest that males tend to have their first admissions earlier than females, perhaps because they cannot be tolerated as easily in the community. This preponderance was also reported for patients who were not admitted as inpatients (6), and therefore it may suggest that males are more vulnerable than females to the psychosocial stresses that are implicated in the causation of schizophrenia.

These findings have implications for public policy in the provision of acute psychiatric services, particularly in situations where the number of conventional acute psychiatric beds is limited. Of particular interest is the absence of compulsory legal detention on the general medical wards. In Jamaica, common law facilitates admission and treatment of acutely ill psychiatric patients in exactly the same way as for patients with acute, often life-threatening, medical conditions where consent for treatment is not available (16).

Our study is limited by sample size, with admissions to the general medical wards and the community psychiatric units being relatively small. It is also limited by the brevity of the 12-month follow-up period and by the location of all of the general medical wards in rural areas. Although the limitations of retrospective case-note data are recognized, this study was not retrospective in the usual sense that observations were made retrospectively. The case notes documented the progress of each patient prospectively over 12 months of a first-episode sample for clinical and service reasons, with the distinct advantage that clinicians made their observations and decisions independently of any research hypotheses. Birchwood and colleagues (12) pointed out that in any study in which one of the main outcome variables is likely to be influenced by the degree of surveillance of cases, truly prospective designs bring their own problems, and therefore quasi-retrospective studies such as this one are an important complement.

Unlike the sample in the study by Birchwood and his colleagues in the United Kingdom, our sample was identified prospectively, and the initial assessment and observation of symptoms were made by one clinician using a recognized standardized diagnostic instrument. The results of this study in Jamaica suggest that an improved outcome for acute schizophrenia and other acute psychiatric illness is closely related to treatment in open medical wards of general hospitals. Whether this finding is applicable to other countries is a question for further research.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Theodore and Vada Stanley Foundation for the research award that funded this study and E. Fuller Torrey, M.D., and Gerard Hutchinson, D.M., for their positive support.

Dr. Hickling is medical director of Psychotherapy Associates International, Ltd., Haverstock House, 81–83 Villa Road, Handsworth, Birmingham B19 1NH, England (e-mail, [email protected]). Ms. McCallum and Mr. Nooks are mental health officers in the Ministry of Health and Environmental Control in Kingston, Jamaica. The late Dr. Rodgers-Johnson was professor of experimental medicine on the faculty of medical science at the University of the West Indies in Mona, Kingston, Jamaica.

|

Table 1. Severity of positive and negative symptoms, as measured by Krawiecka and associates' scale1, for 120 patients with first-contact schizophrenia treated in three types of inpatient facilities in Jamaica in 1992

|

Table 2. Outcome and clinical status of 120 patients with first-contact schizophrenia 12 months after discharge from three types of inpatient facilities in Jamaica1

1. Ottey F: A Psychiatric Service for Eastern Jamaica. Thesis for the degree of doctor of medicine, psychiatry. Mona, Jamaica, University of the West Indies, 1973Google Scholar

2. Hickling FW: The effects of a community psychiatric service on the mental hospital population in Jamaica. West Indian Medical Journal 25:101-106, 1976Medline, Google Scholar

3. Hickling FW: Psychiatric hospital admissions in Jamaica, 1971-1988. British Journal of Psychiatry 159:817-821, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Abel W: Developing Mental Health Services in Rural Jamaica. Thesis for the degree of doctor of medicine, psychiatry. Mona, Jamaica, University of the West Indies, 1994Google Scholar

5. Hickling FW: Deinstitutionalization and community psychiatry in Jamaica. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:1122-1126, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Hickling FW, Rodgers-Johnson P: The incidence of first contact schizophrenia in Jamaica. British Journal of Psychiatry 167:193-196, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Demographic Statistics, Jamaica 1992. Kingston: Statistical Institute of Jamaica, 1993Google Scholar

8. Jablensky A, Sartorius N, Ernberg G, et al: Schizophrenia: manifestations, incidence, and course in different cultures: a World Health Organization ten-country study. Psychological Medicine Monograph 20 (suppl):1-97, 1992Google Scholar

9. Wing J, Cooper J, Sartorius N: The Description and Classification of Psychiatric Symptomatology: An Instruction Manual for the PSE and CATEGO. London, Cambridge University Press, 1974Google Scholar

10. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), Interview Manual. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1987Google Scholar

11. Krawiecka M, Goldberg D, Vaughn M: A standardized psychiatric assessment scale for rating chronic psychotic patients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 55:299-308, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Birchwood M, Cochrane R, Macmillan F, et al: The influence of ethnicity and family structure on relapse in first-episode schizophrenia: a comparison of Asian, Afro-Caribbean, and white patients. British Journal of Psychiatry 161:783-790, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Wing JK, Brown GW: Institutionalization and Schizophrenia. Maudsley Monograph. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1970Google Scholar

14. Freeman H: Schizophrenia and city residence. British Journal of Psychiatry 164 (suppl)23:39-50, 1994Google Scholar

15. Newman-Williams M, Sabatini S: Child Centered Development and Social Progress in the Caribbean, in Poverty, Empowerment, and Social Development in the Caribbean. Edited by Girvan N. Kingston, Jamaica, Canoe Press, 1995, p 63Google Scholar

16. Hickling FW: Transforming mental health legislation (ltr). Psychiatric Bulletin 23:115, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar