Utility of Routine Drug Screening in a Psychiatric Emergency Setting

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study determined whether dispositions from an urban psychiatric emergency service would differ between patients who received a mandatory urine drug test and those who may or may not have had a test based on the attending psychiatrist's clinical judgment. The accuracy of clinicians' suspicion of substance use among mandatorily screened patients was also examined. METHODS: A total of 392 consenting patients presenting to an urban psychiatric emergency service were randomly assigned to a mandatory-screen group (N=198) or a usual-care group (N=194). Physicians ordered screens based on clinical judgment. Additional screens were performed without physicians' knowledge for patients in the mandatory-screen group for whom no screen was ordered. Demographic and clinical information, results of drug screens, and information about dispositions were collected from clinical charts or hospital databases. RESULTS: No difference in dispositions was found between the mandatory-screen group and the usual-care group. Survival analysis did not reveal a difference between the two groups in length of stay in inpatient psychiatric units. As for accuracy of physicians' suspicion of substance use, positive drug screens were recorded for 10.2 percent of the 198 patients in the mandatory-screen group who did not admit drug use or for whom physicians did not expect drug use. A total of 39.3 percent of the patients who were suspected of use and 88.2 percent of those who admitted use had positive drug screens. Only 20.8 percent of patients who denied substance use had positive screens. CONCLUSIONS: Routine urine drug screening in a psychiatric emergency service did not affect disposition or the subsequent length of inpatient stays. The results do not support routine use of drug screens in this setting.

Substance use disorders are common among patients who present to psychiatric emergency services (1). Substance use can exacerbate psychiatric symptoms and independently precipitate emergency service visits (2). Emergency psychiatrists frequently face difficult and complex decisions about the contribution, if any, of substance use to the clinical presentation of patients. Appropriate treatment dispositions depend on the accuracy of such decisions.

Urine drug testing more accurately detects the presence of substance use than do clinical interviews, patients' self-reports, and diagnostic questionnaires. Substance use disorders are often unreliably diagnosed in psychiatric emergency settings (3,4); patients' self-reports of drug use may not be reliable, and patients may underreport drug use (5,6).

The use of standardized questionnaires can be helpful. For example, one study in a psychiatric emergency room found a one-third increase in the diagnosis of substance-induced organic mental disorders when a standardized questionnaire was used (7). However, in another study in a psychiatric emergency service, results of urine drug screens obtained routinely for all patients were compared with results of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (8). The SCID failed to identify 55 percent of cocaine-abusing patients (8).

Clinicians' overall suspicion of substance use has not proven particularly accurate. In one study of patients without primary substance abuse diagnoses who presented to a psychiatric emergency room, clinicians suspected that 94 of 205 patients (45.9 percent) had used substances (9,10). However, only 31 patients in this subset (33 percent) had positive urine screens. Clinicians did not suspect substance use for 111 patients (54.1 percent), and urine drug tests were positive in 25 of the unsuspected cases (22.5 percent).

Urine drug testing is an accurate but problematic method of detecting substance use. Patients often are unwilling or unable to provide samples. In busy emergency departments, it can also be difficult for staff to make sure that patients provide samples. Waiting time for results may also be relatively long, which may delay dispositions of patients, burdening busy emergency services. Finally, urine drug testing can be expensive.

The question arises as to whether it is useful to conduct routine drug screens for all patients admitted to psychiatric emergency services. Some authors strongly recommend routine testing (8). However, from an economic perspective, it is not sufficient to establish that routine screening detects more patients with substance use disorders. Routine screening should also warrant the additional cost. In a psychiatric emergency service it is important to determine whether routine screening affects the key functions of evaluation and disposition of patients. One study recommended routine screening based on the finding that psychotic patients with positive urine drug tests received more intense care in the psychiatric emergency department and were more often hospitalized (9). However, these findings may indicate that substance-using psychotic patients had clinical presentations that required more intense treatment, not that urine drug test results affected treatment.

The study reported here was a randomized controlled trial examining the utility of urine drug testing. The primary question was whether dispositions from a psychiatric emergency service would differ for patients who received a routine mandatory urine drug screen and those who received a urine screen only if psychiatrists' clinical judgment deemed it useful. In addition, the study examined the accuracy of clinicians' suspicions about patients' substance use.

We also investigated which psychiatric symptoms were associated with psychiatrists' decisions to order drug screens. Thus one purpose of the study was to identify an algorithm to trigger an order for a drug screen. We also examined the psychiatric symptoms associated with use of various drugs, and we hypothesized that significant associations would be found between stimulant abuse and psychotic symptoms and between opiate and cocaine abuse and suicidal ideation.

Methods

All patients presenting to the psychiatric emergency service of San Francisco General Hospital between July 17, 1997, and September 26, 1997, were asked to provide informed consent to participate in the study. We randomly assigned consenting patients to either a mandatory-drug-screen group or a usual-care group. Psychiatrists, who were blind to patients' consent and randomization status, ordered urine drug screens for patients in both groups if in their clinical judgment a screen was needed. Drug screens were then automatically ordered for all remaining patients in the mandatory-screen group. A total of 198 patients were in the mandatory-drug-screen group, and 194 were in the usual-care group.

We collected demographic and clinical information from hospital records. The psychiatric emergency service's clinical forms record psychiatrists' suspicions or patients' self-reports of substance use, detailing the particular substances involved. We obtained information about patients' dispositions from hospital databases.

Results of urine drug screens were obtained from hospital databases. The screens tested for ethanol, amphetamine and methamphetamine, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, cocaine, opiates, and methadone. Screening was conducted with standard immunoassays, and confirmatory tests were done for positive screens. Cutoff concentrations for positive results were similar to those in recommendations from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (11). Test results were often not available to psychiatrists before patients were discharged from the emergency service. Clinical data and experience indicate that test results were available less than half the time. However, it should be noted that clinicians have the option to keep patients longer to obtain drug screen results before discharge if it is felt to be clinically appropriate.

We compared the differences in dispositions between the two groups using chi square tests. We used logistic regression analysis to examine factors influencing psychiatrists to order drug screens and to investigate the relationship between psychiatric symptoms and drug use. Survival analysis was used to examine the effects of drug screens on inpatient lengths of stay. All statistical tests were conducted using the SAS 6.12 statistical package.

Results

Demographic characteristics and substance abuse

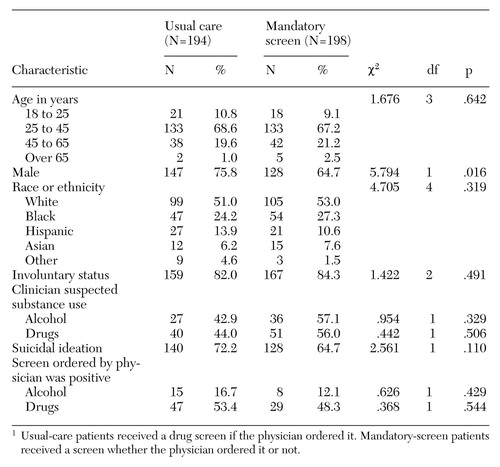

Information about patients' demographic characteristics is reported in Table 1. Of note, the usual-care group had a significantly higher proportion of males (χ2=5.79, df=1, p=.016), despite random assignment.

We previously reported in detail the incidence and pattern of substance abuse in this sample and the ethnic differences among the substance users in the sample (12). Briefly, in the mandatory-screen group, 53 patients (43.4 percent) tested positive for any substances, 45 (36.9 percent) tested positive for any drugs of abuse, and eight (6.6 percent) tested positive for alcohol only. Cocaine was present in 28 of the positive screens (62.2 percent). Given the limitations of urine testing for alcohol use, which detects alcohol only as long as it is present in the blood, all other results pertain to drug use.

Disposition

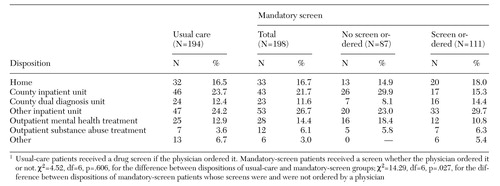

The primary study question was whether routinely ordering drug screens affected patients' dispositions from the psychiatric emergency service. We found no significant differences in dispositions between the usual-care group and the mandatory-screen group. Table 2 presents data on referral to inpatient or outpatient psychiatric treatment, referral to inpatient or outpatient substance abuse treatment, or discharge home without a referral. We also compared patients in the usual-care and mandatory-screen groups whom psychiatrists did not suspect of substance use and found no significant differences in disposition.

We compared dispositions of patients for whom a drug screen was ordered by a physician with dispositions of patients for whom no drug screen was ordered. We limited this comparison to the mandatory-screen group. Psychiatrists routinely checked whether urine screen results were available before discharging any patients from the emergency service. A significant difference was found between the dispositions of patients for whom screens were and were not ordered (χ2=14.29, df=6, p=.027). Contingency table analysis indicated that the difference was primarily attributable to the referral of a larger proportion of patients for whom drug screens were not ordered to an inpatient unit in the county hospital (χc2=6.09, df=1, p=.014).

We also examined differences between the usual-care and mandatory-screen groups on a specific aspect of disposition—length of stay after admission to an inpatient unit in the county hospital. Survival analysis did not reveal any significant differences between the two groups. A similar analysis revealed no significant difference in length of stay between those with positive and negative drug screens or between those in the mandatory-screen group for whom drug screens were or were not ordered by physicians.

Accuracy of substance use assessment

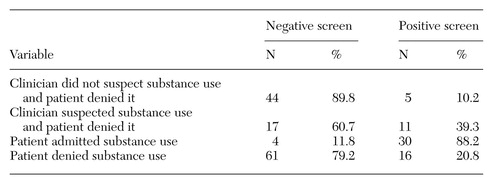

We also assessed clinicians' accuracy in assessing substance use. Table 3 shows how clinicians' suspicions and patients' self-reports of substance use compared with the results of drug screens. Results are reported for the mandatory-screen group only. Of note, only five (10.2 percent) of the patients who were not suspected of substance use and who did not admit use had positive drug screens. In addition, drug screens were positive for 11 patients (39.3 percent) whom clinicians suspected of use and 30 patients (88.2 percent) who admitted use. Of the patients who denied substance use, 16 (20.8 percent) had a positive drug screen.

Psychiatric symptoms

To examine the effects of drug use on psychiatric symptoms, we performed logistic regression analyses with cocaine, opiate, and amphetamine use as independent variables and a variety of symptoms and behaviors as dependent variables. Three statistically significant relationships were found. Patients who tested positive for cocaine use had a decreased likelihood of delusions (odds ratio=.23, p=.005) and violent behavior (OR=.22, p=.05) and an increased likelihood of suicidal ideation (OR=2.97, p=.01).

To identify factors important in psychiatrists' ordering drug screens, we performed logistic regression analyses with physicians' orders for drug screens as the dependent variable; independent variables were presence of delusions, hallucinations, suicidal ideation, homicidal ideation, violent behavior, and a formal thought disorder and the necessity of using restraints. Only the presence of a formal thought disorder was associated with a statistically significant decrease in the likelihood of a physician's ordering a drug screen (OR=.38, p=.03).

We performed a similar logistic regression using age, gender, and race or ethnicity as the independent variables. Screens were less likely to be ordered for older patients (OR=.958, p=.003). The mean age of patients for whom a drug screen was not ordered was 40.4 years, compared with 36 years for those for whom a screen was ordered.

Discussion and conclusions

The major finding of this study is that mandatory urine drug screening in a psychiatric emergency service did not affect the disposition of patients, whether in referral to inpatient or outpatient psychiatric treatment, referral to inpatient or outpatient substance abuse treatment, or discharge home without a referral. While dispositional issues are of prime importance in the emergency setting, it may be that information from routine drug screens has other benefits, such as in verifying relapse to drug use for outpatient clinicians who are able to obtain information from their patients' emergency visits. On the other hand, one major variable outside of the emergency setting that we were able to examine—inpatient length of stay—did not differ for patients who were mandatorily screened for substance use.

To put this finding in context, during the study period, Medicare reimbursement for a urine drug test was $133.22, although it should be noted that reimbursements are not equivalent to costs. For the 198 patients in the mandatory-screen group, 57 of the screens (28.8 percent) were administered mandatorily rather than by a physician's order. Over the two months of the study, about 1,200 patients presented to the psychiatric emergency room. If routine mandatory screening had been implemented for all patients during that time and if the same proportion of patients had not received a screen by a physician's order, the mandatory screens would have cost an additional $46,041, over and above the $84,728 costs for the screens ordered by physicians. These additional costs would have amounted to $275,000 over one year.

A second important finding was that at least in the urban psychiatric emergency service studied, in which substance abuse is extremely common, clinicians were accurate in their suspicions about use. The issue of particular importance is whether clinicians are not detecting patients' substance use that is later detected by urine drug screening. We found that in only 10 percent of cases did physicians fail to detect substance use later revealed by screening. Further, when clinicians suspected use, their suspicions were correct approximately 40 percent of the time. However, this figure probably underrepresents the physicians' accuracy, in that suspicion of substance use was not necessarily suspicion of acute use. Clinicians generally noted that their suspicion was based on patients' history of use, although many patients had not used drugs in the days before admission. Our results also indicated that when patients did admit to substance use, they were generally forthright.

We also attempted to identify symptoms or behaviors associated with psychiatrists' ordering drug screens. We expected to find that they would be more likely to order drug screens for patients with psychotic symptoms, particularly hallucinations. In fact, the only significantly related symptom was the presence of a formal thought disorder—psychiatrists were less likely to order drug screens for these patients (OR=.38). It may be that psychiatrists tend to view a formal thought disorder as evidence of an endogenous, non-substance-induced psychotic disorder rather than as substance-induced psychosis.

We were also surprised to find that neither sex nor ethnicity predicted orders for drug screens, although we did expect that screens would more likely be ordered for younger patients. Our analysis did not readily yield a quantifiable formula for ordering drug screens that could be applied as a useful algorithm in the psychiatric emergency setting.

Because we had the results of patients' drug screens, we had the opportunity to study the relationship between specific drugs and symptoms. In our earlier report on the same sample, we noted that amphetamine and methamphetamine use is particularly common in San Francisco, compared with cities in the eastern U.S. (12). The clinical impression in the psychiatric emergency service is that a large number of patients present with hallucinations, paranoia, or a formal thought disorder as a result of amphetamine or methamphetamine use. However, our data did not support this relationship. Surprisingly, cocaine use was negatively correlated with delusions (OR=.23) or violent behavior (OR=.22). However, cocaine users were more likely to have suicidal ideation (OR=2.97).

One limitation of this study is that we examined disposition from the psychiatric emergency service based on whether drug screens were ordered by physicians, independent of whether the results of the screens were received before disposition. However, this naturalistic study was done in a real-world, clinical setting. In such a setting, it takes time to collect samples, send them to the laboratory, and wait for the results. Dispositional decisions often have to be made before results are returned. This consideration is integral to the question of whether drug screens should be routinely ordered in the psychiatric emergency room. If a test were available that offered immediate results, the utility of urine drug screens in this clinical setting might differ.

Another weakness of the study is that the patients who consented to participate may have differed from the nonconsenters, although the two groups appeared equivalent. Thus the findings might not be generalizable to all patients in the psychiatric emergency service. This issue was previously addressed in the same sample (12). That study found no significant differences between consenting and nonconsenting patients in gender, race or ethnicity, or discharge diagnosis; however, the consenting subjects were significantly younger than the nonconsenting subjects (37.5 years versus 39.1 years; p=.025). Also, although drug screens were ordered for a significantly smaller proportion of the nonconsenters than the consenters (30 percent versus 47.2 percent; p=.005), the proportions of positive screens in the two groups were not significantly different (42.9 percent versus 53.3 percent).

Given the lack of difference in dispositions of patients in the mandatory-screen and usual-care groups, the lack of difference between the two groups in length of inpatient stays, and the general accuracy of psychiatric emergency service clinicians in assessing substance use, there does not appear to be a compelling reason to routinely order drug screens in this setting. We did not examine all possible benefits of routine screening, but other possible benefits, such as documenting lapses in sobriety, do not appear to warrant the cost of routine screening. We therefore recommend that psychiatrists order drug screens when warranted by their clinical concerns in the emergency setting.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kate Beyrer, M.D., Mark Leary, M.D., and Aline Wommack, R.N., M.S., for help in initiating and conducting the study; John Osterloh, M.D., M.S., for providing expertise on toxicology screens; and Michele Okun, M.S., for her contributions to conducting the study. Dr. Batki's contribution to this work was partly supported by grants R01-DA-11397 and P50-DA-09253 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Dr. Schiller is assistant clinical professor, Dr. Shumway is assistant professor, and Dr. Batki was formerly clinical professor at the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Batki is currently professor at the State University of New York Health Science Center-Syracuse. Dr. Schiller is also an attending psychiatrist at San Francisco General Hospital. Send correspondence to Dr. Schiller in the department of psychiatry at San Francisco General Hospital, 7M-Ward 21, 1001 Potrero Avenue, San Francisco, California 94110 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 392 patients in a psychiatric emergency service assigned to a usual-care or a mandatory-drug-screen group1

|

Table 2. Disposition of 392 patients in a psychiatric emergency service assigned to a usual-care or a mandatory-drug-screen group1

|

Table 3. Clinicians' suspicions and patients' self-reports about substance use among 198 patients in a psychiatric emergency service, by whether a mandatory drug screen was negative or positive

1. Dhossche D, Rubinstein J: Drug detection in a suburban psychiatric emergency room. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 8:59-69, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Breslow RE, Klinger BI, Erickson AJ: Acute intoxication and substance abuse among patients presenting to a psychiatric emergency service. General Hospital Psychiatry 18:183-191, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Jones GH: The recognition of alcoholism by psychiatrists in training. Psychological Medicine 9:789-791, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Lieberman PB, Baker FM: The reliability of psychiatric diagnosis in the emergency room. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 36:291-293, 1985Abstract, Google Scholar

5. McNagny SE, Parker RM: High prevalence of recent cocaine use and the unreliability of patient self-report in an inner-city walk-in clinic. JAMA 267:1106-1108, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Crowley TJ, Chesluk D, Dilts S, et al: Drug and alcohol abuse among psychiatric admissions: a multidrug clinical-toxicologic study. Archives of General Psychiatry 30:13-20, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Szuster RR, Schanbacher BL, McCann SC: Characteristics of psychiatric emergency room patients with alcohol- or drug-induced disorders. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:1342-1345, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Elangovan N, Berman S, Meinzer A, et al: Substance abuse among patients presenting at an inner-city psychiatric emergency room. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:782-784, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

9. Claasen CA, Gilfillan S, Orsulak P, et al: Substance use among patients with a psychotic disorder in a psychiatric emergency room. Psychiatric Services 48:353-358, 1997Link, Google Scholar

10. Gilfillan S, Claasen C, Orsulak P, et al: A comparison of psychotic and nonpsychotic substance users in the psychiatric emergency room. Psychiatric Services 49:825-828, 1997Link, Google Scholar

11. Department of Health and Human Services: Mandatory guidelines for federal workplace drug testing programs: final guidelines notice. Federal Register 53:11969-11989, 1989Google Scholar

12. Schiller MJ, Shumway M, Batki SL: Patterns of substance use among patients in an urban psychiatric emergency service. Psychiatric Services 51:113-115, 2000Link, Google Scholar