Burnout Among Relatives of Psychiatric Patients Attending Psychoeducational Support Groups

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The effectiveness of family interventions may be improved by concentrating on elements of objective burden that best predict subjective burden. The relationship between subjective burden and objective burden was investigated among caregivers of patients with serious mental illness in the Netherlands who were attending psychoeducational support groups. METHODS: The study used pretest data from an intervention study in which psychoeducational family support groups in the Netherlands were evaluated. A total of 164 participants from 19 psychoeducational groups organized by nine community mental health centers completed the Dutch translation of the Maslach Burnout Inventory and the Involvement Evaluation Questionnaire. Regression analyses were conducted, with elements of subjective burden as dependent variables and elements of objective burden, demographic characteristics, and characteristics of the patient's disorder as predictors. RESULTS: Burden in general and emotional exhaustion were the aspects of subjective burden best predicted by objective burden. In two regression models, objective burden together with the other predictors explained 57 percent and 54 percent of the variance in subjective burden. Two aspects of objective burden—strain on the relationship with the patient and ability to cope with the patient's behavior—were related to almost all the investigated aspects of subjective burden. CONCLUSIONS: Strong evidence was found for the relationship between objective and subjective burden and for the hypothesis that particular elements of objective burden contribute more to subjective burden than others. The findings suggest that psychoeducation should concentrate on helping relatives cope with the strain on the relationship with the patient and on improving their ability to cope with the patient's behavior.

Because of the deinstitutionalization of psychiatric patients in recent decades, relatives have become the most important caregivers for adults with major psychiatric disorders (1). Research in this area, which started in the mid-1950s (2), has consistently indicated that the burden on relatives of caring for the patient is considerable and that the relatives' well-being and mental health may become seriously impaired (3).

During the past few decades several psychosocial interventions for relatives of patients with schizophrenia have been developed, varying from one educational session (4) to intensive family interventions of 15 sessions or more (5). Some interventions are aimed at preventing the patient's relapse. Because of the clear relationship between the level of expressed emotion in relatives and relapse (6), these interventions concentrate on diminishing the level of expressed emotion through education, training, and therapy. Effectiveness studies of these interventions have demonstrated a strong effect in preventing relapse fairly consistently (7).

Other interventions are primarily directed at supporting relatives (1). The popularity of supportive interventions in recent years is due both to the gradual realization by professionals that the primary burden and responsibility for care of a mentally ill person lies essentially with the family (8) and to the pleas of the self-help family organizations for more and better support for relatives. These interventions focus on improving relatives' quality of life by reducing stress and burden (1).

Research indicates that these interventions can effectively reduce relatives' burden (9). However, it is not entirely clear which elements of the content and design of the intervention determine its effectiveness. A meta-analysis of 16 effect studies of family interventions found that interventions with less than 12 sessions did not have a significant effect on relatives' burden (9). Other indicators of effectiveness could not be identified.

The content of family interventions varies greatly. In a review Kazarian and Vanderheyden (10) found that most family interventions had an educational element in which information about diagnosis, etiology, course, and treatment of mental illness is given to participants. In several interventions education is the central element, including oral presentations, discussions, question-and-answer periods, and the distribution of written material. Management of the disease is also part of 80 percent of the interventions (10). However, the exact content of this part of the interventions varies considerably. In general, interventions are composed of several different elements, including training in stress management, coping skills, and problem solving, as well as counseling and support and sharing of emotions and advice (9).

The quality of family interventions may be improved by focusing on elements of objective burden that are closely related to subjective burden. Hoenig and Hamilton (11) were the first researchers to differentiate between the objective and subjective dimensions of burden (3,12). Recently, both types of burden have been described by Schene (12) in a comprehensive conceptual framework. Objective burden refers to patients' symptoms and behavior within the social environment and their consequences. Elements of objective burden include disruption of household routines, disruption of relatives' leisure time and career, strain on family relationships, and reduction of social support. Subjective burden relates to the psychological consequences for the family and includes relatives' mental health, subjective distress, and burnout.

In this study we investigated the relationship between subjective and objective burden among caregivers seeking help in psychoeducational family support groups in the Netherlands. We used Schene's conceptual framework (12) of objective and subjective burden and the measures of objective burden he developed on the basis of the framework. The effectiveness of family interventions may be improved by concentrating on elements of objective burden that are the best predictors of subjective burden.

Only a few studies have investigated the elements of objective burden that best predict subjective burden in participants of psychoeducational support groups. Solomon and Draine (13) investigated coping responses of participants and found that available personal resources (the ability of relatives to cope with the illness) was the strongest factor in explaining subjective burden, and that family interventions should focus on improving the family's behavioral response to the illness. Most studies find indications that objective and subjective burden are closely related (3,14), but the evidence is not conclusive (15). Which elements of objective burden are the best predictors of subjective burden is not yet fully understood.

Methods

Subjects and procedure

Pretest data came from an intervention study in which psychoeducational family support groups in the Netherlands were evaluated. The family interventions were conducted as part of regular preventive care at nine community mental health centers in the Netherlands. Participants in the groups were recruited through newspaper advertisements, radio and television talk shows, announcements in newsletters, brochures, and active requests for referrals from private practitioners and social workers. Subjects completed a questionnaire before the groups started and one year later. In this study only data from the first measurement in 1997 were used.

The subjects were recruited from 19 psychoeducational groups. The groups provided information about the disorder, training in coping skills, and counseling and support. The number of sessions varied from six to ten. A total of 164 relatives of mentally ill persons agreed to participate in this study. The questionnaires of two respondents could not be used, and thus the total sample was 162. No data were collected on group participants who were not recruited. Therefore, we do not know how many family members did not take part in the study and why they did not.

Instruments

Instruments were chosen based on the conceptual framework for objective and subjective burden developed by Schene (12). Subjective burden was measured with several instruments. Burnout was measured with the Dutch translation of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) (16). The MBI was designed in the United States for measuring occupational burnout in people-oriented professions, such as health care, social services, criminal justice, and education (17). The MBI items are written in the form of statements about personal feelings or attitudes and are answered on a 7-point scale in terms of the frequency they are experienced.

We rephrased questions from the MBI for use with relatives of patients with a mental illness. In this study we used only the subscale of the MBI measuring emotional exhaustion, because of the growing consensus and empirical support for the view that emotional exhaustion is the best measure of burnout (18). Emotional exhaustion, which was measured by eight items, refers to feelings of being emotionally overextended and depleted of one's emotional resources. We found the internal consistency of the scale to be satisfactory (alpha=.92) and similar to that found by others (16,19,20).

Psychosomatic symptoms of the family members were measured with a list of eight symptoms: headache, muscle pain, lack of appetite, sleeplessness, nervous tension, depressive symptoms, quick temper, and extreme tiredness (21). Each symptom was measured on a 3-point scale expressing how frequently the respondents suffered from it, with 1 indicating never, 2 sometimes, and 3 often. After recoding the scores based on whether the symptom was present or absent, we computed the total number of symptoms.

Finally, subjective burden in general was measured by asking subjects to rate their total feeling of burden on a 5-point scale ranging from 1, not at all, to 5, very much.

Objective burden was measured with the Involvement Evaluation Questionnaire (21), which has been developed as a measure of elements of objective burden as operationalized by Schene (12). Schene and colleagues (14) found four dimensions of caregiving, two of which clearly refer to objective burden. First, urging, which was measured by eight items, refers to activation and stimulation of the patient to take care of himself or herself and to undertake activity. Second, supervision, measured by six items, means ensuring the patient's behavior in such areas as medicine and sleep and guarding against dangerous behavior.

Another scale from the Involvement Evaluation Questionnaire assessed worrying, measured by six items. Worrying refers to concerns about the patient, such as concerns about safety, finances, and health. We also constructed a scale that measured strain on the relationship with the patient, which refers to the stress on the relationship experienced by the relative. All items were scored on a 5-point scale, which we recoded into two categories: 0 indicated never, sometimes, or not or a little; and 1 indicated regularly, often, or always, or rather, much, or very much. The total was calculated for each scale. Finally, two additional items measured objective burden: feeling threatened by the patient and having the ability to cope with the patient's illness.

Demographic variables measured included age and gender of the relative, the relationship to the patient (parent, partner, or other), whether the patient lived in the household, the number of hours of contact with the patient, the patient's disorder (depression, bipolar disorder, psychotic disorder, or other), and the time of onset of the patient's problems.

Analyses

To examine the relationship between subjective and objective burden, we conducted a series of multiple regression analyses with the three elements of subjective burden (emotional exhaustion, psychosomatic symptoms, and burden in general) as dependent variables. The predictors used were the six elements of objective burden (urging, supervision, worrying, strain on the relationship with the patient, feeling threatened by the patient, and ability to cope with the patient's behavior), basic demographic characteristics of the relative, and the disorder of the patient.

As basic demographic characteristics, we used age and gender of the relative and whether the patient lived in the household, as well as dummy variables for the relationship to the patient (parent or partner) and the number of contact hours with the patient (more or less than eight hours a week). For the disorder we constructed the dummy variables of psychotic disorder, depression, bipolar depression, and onset of the illness more or less than two years ago. Predictors with no apparent predictive value (p>.1) for any of the three elements of subjective burden were removed from the regression models.

Results

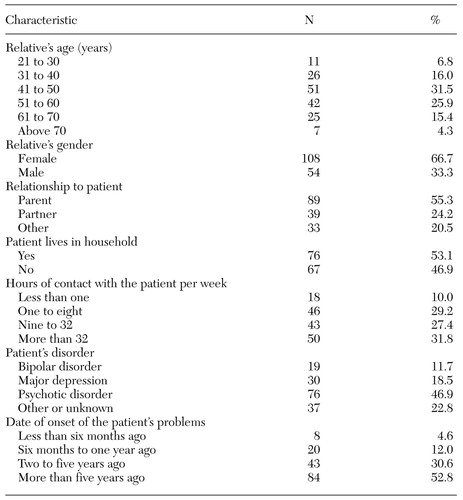

Basic demographic characteristics of the sample of 162 participants in psychoeducational family interventions are presented in Table 1. Most participants in the psychoeducational interventions were female. Their mean± SD age was 49.6±12.7. A little more than half were a parent of the patient, about a fourth were the patient's partner, and about a fifth had another relationship with the patient. Most patients (53.1 percent) were living with the caregiver in the same household. About half of the patients (46.9 percent) had a psychotic disorder, and smaller proportions had bipolar disorder (11.7 percent) or major depression (18.5 percent). Some patients (22.8 percent) had another disorder, or the disorder was not known. In most cases the illness had started at least two years ago.

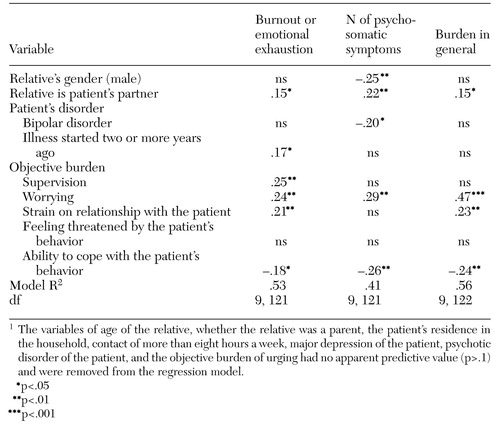

Table 2 summarizes the results of the regression analyses. Burden in general and emotional exhaustion were the aspects of subjective burden best predicted by objective burden. Three of the elements of objective burden together with the other predictors explained 56 percent of the variance of burden in general, and four of the elements together with the other predictors explained 53 percent of emotional exhaustion.

Two aspects of objective burden—ability to cope with the patient's behavior and worrying—were related to all the investigated aspects of subjective burden. If the relative felt more able to cope with the patient's behavior, the relative's burnout, psychosomatic symptoms, and burden in general diminished. Relatives who reported worrying about the patient felt more burdened by the situation than those who worried less: relatives with high scores on worrying also scored high on emotional exhaustion and psychosomatic symptoms.

If the strain on the relationship with the patient increased, the burden on the relatives (emotional exhaustion and burden in general) also increased. Finally, the caregiver's task of supervising the patient was positively related to emotional exhaustion.

The amount of subjective burden was not predicted by the extent of the relative's urging the patient in daily life, such as urging the patient to care for himself or herself.

In our analyses of the relationship between subjective and objective burden, we controlled for demographic variables and characteristics of patients' illnesses. We found some interesting relationships between demographic characteristics and subjective burden, although these relationships were not the main focus of our study. First, we found some indications that the patient's disorder and its time of onset were directly related to the subjective burden of the relative. We found less burnout (emotional exhaustion) among relatives of patients with bipolar disorder compared with other caregivers, and the relatives of patients with bipolar disorder also experienced fewer psychosomatic symptoms. Furthermore, we found that if the illness had started two or more years ago, relatives scored higher on emotional exhaustion than if the disorder had started more recently.

Second, we found some significant relationships between demographic characteristics of the caregivers and subjective burden. Partners experienced more emotional exhaustion, psychosomatic symptoms, and burden in general than other relatives. Men were found to suffer fewer psychosomatic symptoms than women. Age of the caregiver, living in the same household as the patient, and the number of hours of contact were not found to be related to subjective burden.

Discussion and conclusions

Our study has several limitations. First, the psychoeducational support groups we examined were not standardized and may have differed in target population, contents, and format. Second, no data were available on nonresponders. Third, we measured subjective burden with the Netherlands version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory, which was designed for measuring occupational burnout in people-oriented professions. Whether this instrument is valid for measuring burnout in relatives of persons with mental illness has to be confirmed.

A fourth limitation has to do with our operationalization of objective and subjective burden. The conceptual framework of Schene (12) was used, and for this reason we also used his operationalization of objective burden. However, some of the measures of objective burden could also be interpreted as subjective burden, as, for example, worrying. Because of this unclear distinction, the relationship we found between objective and subjective burden could be explained by the variables that actually measure subjective burden.

Despite these limitations, we did find evidence that the subjective burden of participants in psychoeducational support groups is high. The relatives in our intervention scored higher on emotional exhaustion (burnout) than nurses examined by Maslach and Schaufeli (17). In addition, our subjects experienced more psychosomatic symptoms than the relatives of psychotic and depressive patients in the studies of Schene and Van Wijngaarden (22) and Van Wijngaarden and associates (23).

The demographic characteristics of the participants of the psychoeducational support groups in our study were very similar to those of family caregivers in the United States (13,24,25,26). Therefore, our results may be safely generalized to other caretaking families.

We hypothesized that the quality of family interventions may be improved by focusing on elements of objective burden that are closely related to subjective burden. We found evidence that relatives' ability to cope with the patient's behavior, worrying about the patient, and the strain on the relationship with the patient were strongly related to subjective burden. Concentrating psychoeducational support groups on these elements by teaching relatives how to cope with patients' behavior and with feelings of worry and how to improve the relationship with the patient may improve the capacity of these groups to reduce burden, but further research is needed to confirm this approach.

According to the findings of Solomon and Draine (13) and Schene and his colleagues (14), demographic characteristics of the caregiver and the patient's disorder do not contribute much to subjective burden compared with the elements of objective burden. In our study, we did find some important correlations. We found indications that caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder experienced less burden than other caregivers and that if the illness started two or more years ago, caregivers suffered more subjective burden. These findings can be interpreted as an indication that it is better to organize support groups for different categories of relatives depending on the disorder, which is not always done in practice (27).

We found evidence that the subjective burden on partners is higher than on other caregivers. These findings can be interpreted as support for the conclusion of Mannion and associates (27) that a psychoeducational group specifically designed for spouses could be useful because the issues and needs of spouses differ from those of other relatives of mentally ill persons. Further research is needed in this area.

The authors are affiliated with the Trimbos Institute, the Netherlands Institute of Mental Health and Addiction, P.O. Box 725, 3500 AS Utrecht, the Netherlands (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristic of 162 participants in psychoeducational family interventions in the Netherlands

|

Table 2. Standardized regression coefficients of objective burden, demographic variables, and the patient's disorder in relation to subjective burden among paricipants in psychoeducational family interventions in the Netherlands1

1. Solomon P: Moving from psychoeducation to family education for families of adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 47:1364-1370, 1996Link, Google Scholar

2. Clausen JA, Yarrow MR: The impact of mental illness on the family. Journal of Social Issues 11:3-64, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Maurin JT, Boyd CB: Burden of mental illness on the family: a critical review. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 2:99-107, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Cozolino LJ, Goldstein MJ, Nuechterlein KH: The impact of education about schizophrenia on relatives varying in expressed emotion. Schizophrenia Bulletin 14:675-687, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Falloon IR, Boyd JL, McGill CW, et al: Family management in the prevention of exacerbation of schizophrenia: a controlled study. New England Journal of Medicine 306:1437-1440, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Kuipers L, Bebbington P: Expressed emotion research in schizophrenia: theoretical and clinical implications. Psychological Medicine 18:893-909, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Lam DH: Psychosocial family intervention in schizophrenia: a review of empirical studies. Psychological Medicine 21:423-441, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Katschig H, Konieczna T: What works in work with the relatives? A hypothesis. British Journal of Psychiatry 155(suppl 5):144-150,1989Google Scholar

9. Cuijpers P: The effects of family interventions on relatives' burden: a meta-analysis. Journal of Mental Health 8:275-285, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Kazarian SS, Vanderheyden DA: Family education of relatives of people with psychiatric disability: a review. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 15:67-84, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Hoenig J, Hamilton MW: The schizophrenic patient in the community and his effect on the household. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 12:165-176, 1966Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Schene AH: Objective and subjective dimensions of family burden: towards an integrative framework for research. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 25:289-297, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Solomon P, Draine J: Subjective burden among family members of mentally ill adults: relation to stress, coping, and adaptation. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 3:419-427, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Schene AH, Van Wijngaarden B, Koeter MWJ: Family caregiving in schizophrenia: domains and distress. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:609-618, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Jones SL, Roth D, Jones PK: Effect of demographic and behavioral variables on burden of caregivers of chronic mentally ill persons. Psychiatric Services 46:141-148, 1995Link, Google Scholar

16. Schaufeli W, Van Dierendonck D: Maslach Burnout Inventory, Nederlandse versie (MBI-NL) [Dutch version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory]. Utrecht, the Netherlands, University of Utrecht, 1995.Google Scholar

17. Maslach C, Schaufeli WB: Historical and conceptual development of burnout, in Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research. Edited by Schaufeli WB, Maslach C, Marek T. Washington, Taylor & Francis, 1993Google Scholar

18. Dietzel LC, Coursey RD: Predictors of emotional exhaustion among nonresidential staff persons. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 21:340-348, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Maslach C, Jackson SE: MBI, Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual, Research Edition. Palo Alto, Calif, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1986Google Scholar

20. Schaufeli WB, Van Dierendonck D: The construct validity of two burnout measures. Journal of Organizational Behavior 14:631-647, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Schene AH, Van Wijngaarden B: The Involvement Evaluation Questionnaire. Amsterdam, University of Amsterdam, Department of Psychiatry, 1992Google Scholar

22. Schene AH, Van Wijngaarden B: Familieleden van mensen met een psychotische stoornis: een onderzoek onder Ypsilonleden [Family members of people with a psychotic disorder: a study among members of Ypsilon]. Amsterdam, University of Amsterdam, Department of Psychiatry, 1993Google Scholar

23. Van Wijngaarden B, Schene AH, Koeter M: De consequenties van depressieve stoornissen voor de bij de patiënt betrokkenen: een onderzoek naar de psychometrische kwaliteiten van de betrokkenen evaluatie schaal [The consequences of depressive disorders for patients' relatives: a psychometric study of the Involvement Evaluation Questionnaire]. Amsterdam, Academisch University of Amsterdam, Department of Psychiatry, 1996Google Scholar

24. Rauktis ME, Koeske GF, Tereshko O: Negative social interactions, distress, and depression among those caring for a seriously and persistently mentally ill relative. American Journal of Community Psychology 23:279-299, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Reinhard SC, Horwitz AV: Caregiver burden: differentiating the content and consequences of family caregiving. Journal of Marriage and the Family 57:741-754, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

26. Stueve A, Vine P, Streuning EL: Perceived burden among caregivers of adults with serious mental illness: comparison of black, Hispanic, and white families. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 67:199-209, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Mannion E, Mueser K, Solomon P: Designing psychoeducational services for spouses of persons with mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal 30:177-190, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar