Effects of an Outreach Intervention on Use of Mental Health Services by Veterans With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study examined the effectiveness of an outreach intervention designed to increase access to mental health treatment among veterans disabled by chronic posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and identified patient-reported barriers to care associated with failure to seek the treatment offered. METHODS: Participants were 594 male Vietnam veterans who were not enrolled in mental health care at a Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center but who were receiving VA disability benefits for PTSD. Half the sample was randomly assigned to an outreach intervention, and the other half was assigned to a control group. Veterans in the intervention group received a mailing that included a brochure describing PTSD treatment available at an urban VA medical center, along with a letter informing them about how to access care. Participants in the intervention group were subsequently telephoned by a study coordinator who encouraged them to enroll in PTSD treatment and who administered a survey assessing barriers to care. RESULTS: Veterans in the intervention group were significantly more likely than those in the control group to schedule an intake appointment (28 percent versus 7 percent), attend the intake (23 percent versus 7 percent), and enroll in treatment (19 percent versus 6 percent). Several patient-identified barriers were associated with failure to seek VA mental health care, such as personal obligations that prevented clinic attendance, inconvenient clinic hours, and current receipt of mental health treatment from a non-VA provider. CONCLUSIONS: Utilization of mental health services among underserved veterans with PTSD can be increased by an inexpensive outreach intervention, which may be useful with other chronically mentally ill populations.

Access to services has been identified as a core domain in performance evaluation of health care systems, including mental health care organizations (1). The advent of managed care has led to a growing concern that underserved individuals with chronic mental illness will have increasing difficulty accessing public sector mental health services (1,2).

As reported by the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study (NVVRS) (3), Vietnam veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) constitute a large group of chronically mentally ill individuals who have historically underutilized mental health services. Rates of use reported by the NVVRS in 1990 were 22 percent for males and 55 percent for females. Use of mental health services by veterans with PTSD has increased considerably over the past decade, with implementation of specialized treatment programs within VA (4). However, despite these improvements, a significant minority of veterans disabled by PTSD, 38 percent, still do not receive current mental health care from VA medical centers and may be underserved (5).

A number of patient- and system-level factors are related to underutilization of psychiatric services among people with mental disorders (1). Patient-identified physical barriers, such as distance from a treatment program and severe physical health problems, have been found to decrease participation in mental health treatment (1,6). Attitudinal factors may also impede pursuit of mental health care, including lack of confidence in treatment, fear of stigmatization, and beliefs that some problems, such as alcohol dependence, are not severe enough to justify treatment (7,8,9). The reduced likelihood of seeking treatment among individuals with PTSD has been attributed to a desire to avoid confronting painful memories (10), negative perceptions of governmental institutions (11), and institution- or system-induced difficulties in accessing timely and efficient care (12).

Outreach activities have proven successful in increasing utilization of health care services by underserved populations in medical and mental health settings. These interventions have typically included informational pamphlets or appointment reminders mailed to potential service users or direct telephone calls. Such methods have been used effectively to engage individuals in smoking cessation programs (13) and to increase treatment compliance among cocaine abusers (14).

Outreach efforts have also proven successful in increasing rates of participation in mammography screening programs (15,16) and Medicaid well-child health screenings (17). At least one study demonstrated that combining informational pamphlets with follow-up phone calls addressing barriers to seeking care proved more effective than either method alone (15).

The effectiveness of outreach methods in increasing mental health care utilization among people with chronic mental illness has not been examined in controlled empirical investigations. The primary objective of this study was to determine whether an outreach intervention designed to provide information about available services and improve access to care would be effective in increasing enrollment in mental health treatment among underserved veterans disabled by PTSD. A second objective was to examine associations between patient-identified barriers to care and the effectiveness of the outreach intervention.

Methods

Participants

Participants in the study were 594 male Vietnam veterans living in the vicinity of a large urban VA medical center in Washington State. In 1997 the VA compensation and pension file, a disability payment record, was used to identify all veterans receiving VA disability benefits for PTSD who resided in the state. Veterans were selected for participation based on the following criteria: a zip code in VA records indicating residence within a 50-mile radius of the medical center, receipt of current VA compensation for PTSD resulting from military service in Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War (1965–1973), and no record of use of outpatient mental health or addictions treatment at the VA facility for at least 12 months before the study. The majority of veterans who met these criteria (85 percent) had not received VA outpatient mental health services for at least 48 months before the study, indicating a persistent pattern of nonuse of VA resources for most participants.

Participants were randomly assigned to the intervention group (N=302) or control group (N=292), matched according to city of residence. The mean±SD age of participants in the intervention group was 51.1±3.7 years; it was 51±3.8 years for participants in the control group. Veterans in the intervention and control groups resided a mean±SD distance of 16.4±10.8 and 16.6±10.4 miles from the VA medical center, respectively. The median VA disability rating for PTSD received by veterans in both groups was identical at 30 percent, indicating partial disability.

Interventions

The outreach intervention had two components, a mailing followed by direct telephone contact. The mailing included an informational brochure describing PTSD treatment services available through the local VA medical center and a letter from the director of the PTSD programs and the director of the facility inviting the veteran to seek care. The letter presented participants with three options for responding. They could choose to return an enclosed postcard, call the study coordinator for further information about services or how to schedule an intake appointment, or come to the VA walk-in clinic for an unscheduled appointment.

The second component of the intervention, direct telephone contact, took place approximately one month after the mailing for veterans in the intervention group. Veterans were called by the study coordinator and were asked to participate in a 15-minute survey of possible reasons contributing to their decision not to seek VA mental health treatment in the past. These reasons were assessed by 14 questions addressing physical barriers to accessing care and attitudes toward mental health treatment and the VA health care system. An additional four items assessed participants' treatment history and awareness of mental health resources.

Finally, veterans were asked if they wished to receive specific information about specialized PTSD treatment services available at the VA or through affiliated practitioners serving their community or if they wished to make an appointment to learn more about services or to initiate treatment. Table 1 provides details about the survey questions. The telephone survey also served as an intervention to the extent that it provided an opportunity for veterans to ask questions about services, to schedule an appointment, and to address perceived barriers to receiving care with the study coordinator.

Six months after participants in the intervention received the mailing and outcomes were assessed for that group, veterans in the control group were administered the telephone survey. The purpose of surveying veterans in the control group was to identify a subgroup of individuals that was comparable to the intervention group in their opportunity to seek VA mental health services, as indicated by actual residence in the local community.

Measures

Outcome measures.

Outcome measures included participants' inquiries about treatment via return of postcards to the study coordinator and telephone calls to her, participants' verbal agreements with the study coordinator to schedule an intake appointment with a mental health provider, attendance at an intake assessment session at VA, and attendance at one or more VA follow-up treatment sessions. These outcomes were assessed for the intervention and control samples within six months of sending the mailed component of the intervention to veterans in the intervention group.

Treatment enrollment information was obtained from participants' electronic records at the VA medical center. Specifically, records were examined to determine whether veterans in the intervention and control groups actually scheduled an intake appointment, attended the intake appointment, and kept at least one follow-up treatment appointment with the PTSD clinic or any other mental health specialty clinic. Participants in both groups who entered treatment at VA after the study was initiated but who did so without contacting the study coordinator were also counted as enrollees in treatment. If VA services were not a viable option because of distance, transportation problems, or continued reluctance to come to the VA facility, the veteran's verbal agreement to accept a referral to a community provider to receive services at no charge was also counted as a scheduled intake.

Results

Effectiveness of the intervention

The effectiveness of the outreach intervention was assessed using two different study samples. The intention-to-treat sample was the more inclusive, consisting of all individuals to whom the intervention was mailed. This sample permitted computation of response rates to a large-scale mailing, without verification that the mailed material was received by participants. The second sample, the treated group, included only veterans from the intention-to-treat sample who met three criteria: their mailed material was not returned by the post office, their phone had not been disconnected, and no other evidence existed indicating that they did not live at the address on file with the VA. Using these criteria, 189 veterans in the intention-to-treat sample (62.6 percent) were included in the treated sample. The treated sample provided a means of assessing effectiveness of the intervention with participants who very likely received the intervention.

Fifty-eight veterans expressed interest in treatment to the study coordinator in response to the intervention, which represented 19.2 percent of the intention-to-treat sample and 30.7 percent of the treated sample. Of these veterans, 21 (36.2 percent) called the study coordinator directly, 23 (39.7 percent) returned a postcard asking the study coordinator to call them, and 14 (24.1 percent) agreed to schedule an intake appointment at the time of the telephone survey. Forty-one (70.7 percent) of these veterans scheduled an intake at the VA medical center through the study coordinator, and seven (12.1 percent) agreed to schedule an intake with a community provider. In addition, 11 veterans (3.6 percent) in the intention-to-treat sample scheduled an intake appointment for mental health services at the VA center without contacting the study coordinator for assistance. Of the 52 veterans who scheduled an intake assessment appointment at VA, 47 (90.4 percent) kept their appointment, and 40 (76.9 percent) attended at least one follow-up treatment session.

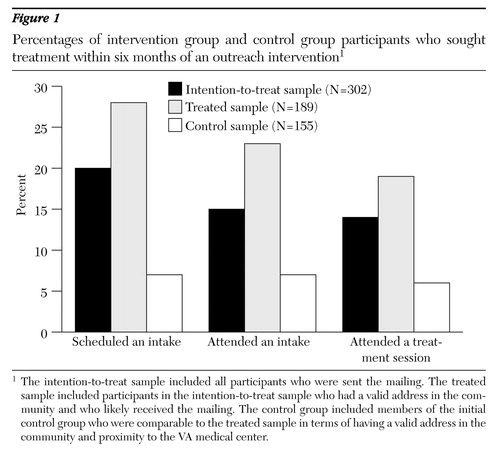

Figure 1 illustrates rates of treatment seeking for the intention-to-treat sample, the treated sample, and the control group. The control group depicted in the figure (N=155) was a subgroup of the original control group that was comparable to the treated sample in terms of having a valid address in the community as established by the criteria described above. Participants in the treated sample were significantly more likely than those in the control group to schedule an intake appointment (27.5 percent versus 7.1 percent; χ2=23.73, df=1, p<.001; N=344), to present for an intake assessment session (22.6 percent versus 7.1 percent; χ2=15.44, df=1, p<.001; N=341), and to attend at least one follow-up treatment session (19.4 percent versus 5.8 percent; χ2=13.55, df=1; p<.001; N=341).

Correlates of effectiveness

The telephone survey responses of participants in the treated sample who sought mental health services were compared with the responses of those who did not. (Survey data were not available for 21 veterans because an earlier version of study procedures did not require telephone survey administration to participants responding to the mailed intervention.) The measure of treatment seeking used in these comparisons was veterans' willingness to schedule a clinic appointment at the VA facility or with a community mental health provider. This outcome measure was used because it was the only marker of treatment seeking available for both VA and community providers. In addition, willingness to schedule an appointment at VA proved highly predictive of veterans' subsequent attendance at the session (90 percent concordance).

Telephone surveys were successfully administered to 104 veterans (56 percent) in the treated sample. Of veterans in this sample who were called, 18 (9.5 percent) did not answer the phone after three or more calls, 44 (23.3 percent) did not call the study coordinator back after she left at least two messages, and four (2.1 percent) declined to participate. Of the 104 individuals in the treated sample who completed the survey, 70 (67.3 percent) indicated that they received and read the mailing sent to them, 20 (19.2 percent) stated that they received but did not read the mailing, and 14 (13.5 percent) stated that they did not receive the mailing.

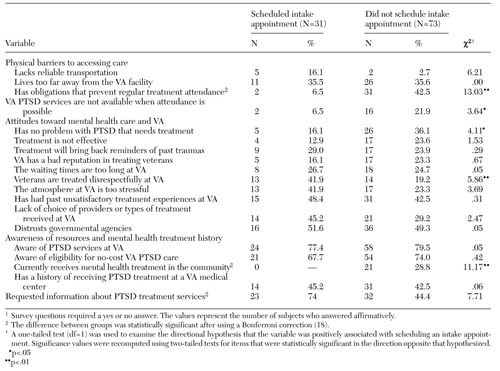

Table 1 compares veterans who sought treatment as a result of the intervention and those who did not on items assessed during survey administration. The table reports uncorrected significance values as well as values that remained significant after a Bonferroni correction was used to adjust an alpha level of p<.05 (18). Uncorrected significance values were reported because stringent control for type I error using the Bonferroni method increases risk for failing to detect meaningful associations (type II error).

Veterans endorsing physical barriers as reasons for not using VA mental health services—namely, unavailability of convenient clinic hours and competing personal obligations that prevented them from attending the clinic—were less likely to respond to the intervention than veterans who did not endorse these barriers. Only three items measuring veterans' attitudes toward mental health treatment and the VA health care system were significantly related to seeking treatment after the intervention. Veterans who believed that they had no problem with PTSD that needed treatment were significantly less likely to seek treatment. Two items concerning negative attitudes toward the VA system discriminated veterans who responded to the intervention from those who did not. These items measured the belief that veterans are treated disrespectfully at VA and the belief that the atmosphere at VA is too stressful. Paradoxically, veterans who endorsed these two items were actually more likely to respond favorably to the intervention, possibly because of the interest and accommodating attitude explicit in the intervention.

As expected, veterans currently involved in community-based mental health treatment were significantly less likely to pursue VA treatment after the intervention. Finally, veterans who expressed interest in learning about VA PTSD treatment services were much more likely to eventually schedule an intake appointment than those who expressed no such interest.

Supplemental analyses were performed to determine if selected demographic variables were associated with effectiveness of the intervention. Veterans who had not been seen for outpatient mental health services at the VA facility within four years of the study were less likely to respond to the intervention than those who had sought services at this facility during those four years. Of the 73 nonresponders, 64 (87.7 percent) had not previously used VA services and nine (12.3 percent) had, whereas 31 (67.7 percent) of responders had not used services and ten (32.3 percent) had (odds ratio=3.39; 95 percent confidence interval=1.21 to 91.45). The VA disability rating for PTSD was unrelated to response to the intervention, as was actual distance from participants' residence to the VA facility.

Discussion and conclusions

This study demonstrated the effectiveness of an outreach intervention in increasing utilization of mental health services by underserved Vietnam veterans receiving disability benefits for PTSD. Veterans who had not used mental health services for an extended period and who received the intervention were significantly more likely than veterans in the control group to schedule an intake appointment (28 percent versus 7 percent), attend the intake interview (23 percent versus 7 percent), and enroll in treatment (19 percent versus 6 percent). Of those who inquired about services described in the mailed material, most followed through by attending subsequent appointments for assessment and treatment of PTSD.

An inexpensive mailed intervention alone was sufficient to prompt treatment seeking among those who responded to the intervention, without the necessity of direct telephone contact by study personnel. However, a subset of veterans (24 percent) responded to the mailed intervention only after receiving a personal phone contact, which afforded them an opportunity for dialogue and information exchange.

The outreach methods used in this investigation may be particularly useful in regions of the country where use of mental health services by veterans with PTSD is below nationally established rates (4).

A minority of veterans surveyed identified physical barriers as reasons for not pursuing VA mental health care in the past. Difficulties imposed by veterans' conflicting obligations and the limited availability of clinic hours were the two physical barriers significantly correlated with poorer outcome of the intervention. These findings suggest the need for expanded operating hours at VA PTSD clinics or support of community-based clinics that improve access to mental health services.

Unfavorable opinions about mental health care and VA not uncommonly were endorsed by the surveyed veterans as reasons for not pursuing VA PTSD treatment. However, participants' response to the outreach intervention was not adversely influenced by a greater tendency to endorse these attitudes. In fact, the intervention proved more effective for veterans who believed that they had been treated disrespectfully by VA in the past or who felt that the atmosphere at VA was too stressful. The resistance of some veterans to seeking VA care may have been rooted in an attitudinal bias that was overcome by the attentive and respectful tone of the study coordinator and by the provision of an easy way to access services.

Veterans who requested information about PTSD services during the telephone survey were also more likely to schedule an intake appointment than those who were not interested in receiving such information. For some veterans, the intervention was effective in initiating treatment seeking because of its educational or informational value. The need for educating this population was further emphasized by the noteworthy percentage of veterans who were unaware of their eligibility for services at no cost and who believed that treatment is ineffective or that it must necessarily stimulate memories of trauma.

On the other hand, more than 75 percent of participants who sought services as a result of the intervention stated that they were already informed of the availability of VA PTSD treatment services. For these individuals, the opportunity for prompt and direct access to care afforded by both components of the intervention may have been more important than education about program resources or content.

Implementing a mailed outreach intervention requires accurate anticipation of resulting increases in workload, so that resources can be appropriately allocated to accommodate respondents in a timely manner. This study showed that many recipients do not receive, or do not read, materials sent to their address of record. Response to a mailed intervention will therefore be attenuated. The finding that less than 20 percent of veterans who were mailed the intervention subsequently kept an intake appointment may assist program administrators in balancing the scope of their outreach interventions against the resources necessary to manage potentially increased numbers of patients.

Participants varied in their preferred method of responding to the intervention. Some mailed back a postcard, some called the telephone number provided, and some simply walked into the VA clinic. Providing a range of possible responses may accommodate special needs or limitations of some individuals and may maximize the success of the intervention.

This investigation included only male Vietnam veterans receiving VA disability benefits for PTSD who resided in a specific region of the country, which limits the generalizability of the findings. In addition, the analysis that identified correlates of response to the intervention was based on data representing only those who could be contacted by telephone and who agreed to participate. However, the methods used in the study may be extended to other groups of veterans traumatized by military service, including women and pre- and post-Vietnam-era war zone veterans. Veterans and nonveterans with chronic mental disorders other than PTSD may also benefit from systematic study of community outreach interventions using the methods demonstrated in this investigation.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center, which was awarded to Veterans Integrated Service Network 20; by the Connecticut-Massachusetts Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center; and by the Northeast Program Evaluation Center. The authors thank John Park, M.B.A., and Joanne Broughm, B.A., for administrative assistance.

Dr. McFall and Ms. Malte are affiliated with the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle. Dr. McFall is also with the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle. Dr. Fontana and Dr. Rosenheck are affiliated with the Northeast Program Evaluation Center of the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System in West Haven and Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut. Send correspondence to Dr. McFall at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System, PTSD Program (1116PTSD), 1660 South Columbian Way, Seattle, Washington 98108 (e-mail, [email protected]).

Figure 1. Percentages of intervention group and control group participants wwho sought treatment within six months of an outreach intervention1

1 The intention-to-treat sample included all participants who were sent the mailingThe treated sample included participants in the intention-to-treat sample who had a valid address in the community and who likely received the mailing. The control group included members of the initial control group ho were comparable to the treated sample in terms of having a valid address in the community and proximity to the VA medical center.

|

Table 1. Variables associated with responses to outreach intervention among male Vietnam receiving VA disability benefits for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)1

1. Rosenheck RA, Stolar M: Access to public mental health services: determinants of population coverage. Medical Care 36:503-512, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Boyle PJ, Callahan D: Managed care and mental health: the ethical issues. Health Affairs 14(3):7-22, 1995Google Scholar

3. Kulka RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, et al: Trauma and the Vietnam War Generation. New York, Brunner/Mazel, 1990Google Scholar

4. Fontana A, Rosenheck R, Spencer H, et al: The Long Journey Home, Vol IV: Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the Department of Veterans Affairs: Fiscal Year 1997 Service Delivery and Performance. West Haven, Conn, Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System, Northeast Program Evaluation Center, 1998Google Scholar

5. Rosenheck RA, DiLella D: Department of Veterans Affairs National Mental Health Program Performance Monitoring System: Fiscal Year 1997 Report. West Haven, Conn, Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System, Northeast Program Evaluation Center, 1998Google Scholar

6. Fortney JM, Booth BM, Blow FC, et al: The effects of travel barriers and age on the utilization of alcoholism treatment aftercare. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 21:391-406, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Cunningham JA, Sobell LC, Sobell, MB, et al: Barriers to treatment: why alcohol and drug abusers delay or never seek treatment. Addictive Behaviors 18:347-353, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Grant BF: Barriers to alcoholism treatment: reasons for not seeking treatment in a general population sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 58:365-371, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Wells JE, Robins LN, Bushnell JA, et al: Perceived barriers to care in St Louis (USA) and Christchurch (NZ): reasons for not seeking professional help for psychological distress. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 29:155-164, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

10. Schwarz ED, Kowalski JM: Malignant memories: reluctance to utilize mental health services after a disaster. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:767-772, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Egendorf A, Kadushin C, Laufer RS, et al: Legacies of Vietnam: Comparative Adjustment of Veterans and Their Peers. New York, Center for Policy Research, 1981Google Scholar

12. Rosenheck RA, Fontana A: Do Vietnam-era veterans who suffer from posttraumatic stress disorder avoid VA mental health services? Military Medicine 160:136-142, 1995Google Scholar

13. Lando HA, Hellerstedt WL, Pirie PL, et al: Brief supportive telephone outreach as a recruitment and intervention strategy for smoking cessation. American Journal of Public Health 82:41-46, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Gottheil E, Sterling RC, Weinstein SP: Outreach engagement efforts: are they worth the effort? American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 23:61-66, 1997Google Scholar

15. King ES, Rimer BK, Seay J, et al: Promoting mammography use through progressive interventions: is it effective? American Journal of Public Health 84:104-106, 1994Google Scholar

16. Taplin SH, Anderman C, Grothaus L, et al: Using physician correspondence and postcard reminders to promote mammography use. American Journal of Public Health 84:571-574, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Selby-Harrington M, Sorenson JR, Quade D, et al: Increasing Medicaid child health screenings: the effectiveness of mailing pamphlets, phone calls, and home visits. American Journal of Public Health 85:1412-1417, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Kirk RE: Experimental Design Procedures for the Behavioral Sciences. Monterey, Calif, Brooks/Cole, 1968Google Scholar