The Impact of Caseload on the Personal Efficacy of Mental Health Case Managers

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The relationship between caseload size and self-perceived clinical effectiveness of mental health case managers was explored. METHODS: A 17-item instrument developed for the study, the Case Manager Personal Efficacy Scale (CMPES), was completed by 300 community mental health case managers in Australia. Efficacy scores were examined in relation to caseload size and to respondents' scores on the General Health Questionnaire. RESULTS: The CMPES was sensitive to changes in caseload size. Case managers with larger caseloads reported lower performance in a range of core role activities. Larger caseload had a weak but significant negative association with general well-being as measured by the General Health Questionnaire. CONCLUSIONS: Caseload size had a significant impact on the self-perceived role performance of mental health case managers. The CMPES is a reliable measure of case manager personal efficacy that is sensitive to variation in work context.

In Australia community mental health services are provided within a clinical case management framework (1) rather than a brokerage framework (2). This approach implies an active hands-on involvement in the life of the consumer and direct provision of clinical treatment services when appropriate. Case management is commonly provided at two levels of intensity.

The most disabled consumers, typically around 10 percent of the client base, receive intensive case management from mobile support teams with extended hours that are modeled on teams in the assertive community treatment approach developed in Madison, Wisconsin, by Stein and Test (3). This model is a highly interventionist assertive approach involving several contacts each week, usually in the form of home visits, with close monitoring of medication and close supervision of the consumer's mental state and social adjustment. Less disabled consumers receive standard case management, which involves service planning and monitoring of general well-being but with considerably more client autonomy. The intensity of service response is based on current needs, and services are not delivered according to a predetermined schedule. These approaches to service delivery are not specific to Australia but rather have come to characterize contemporary practice in the Western world (4).

Case management, as a service delivery approach, has been extensively described from both theoretical and operational perspectives (5,6,7). Although reports on its clinical efficacy have varied (4,8), the approach is well accepted by consumers because it provides the prospect of a stable therapeutic relationship. It appeals to administrators because it provides for clear lines of service accountability. It is also congruent with community expectations that treatment of severe mental illness in local neighborhoods is organized in a way that will ensure treatment compliance and minimize public nuisance or danger.

Despite widespread acceptance and an informative if modest literature on clinical efficacy and cost-benefit (4,8), surprisingly little is known about the service organization and process of case management, especially standard clinical case management. Intensive case management is relatively standardized with respect to team composition, caseload, and modus operandi. However, few descriptions exist of the work practices, team composition, and administration of standard clinical case management. Even less is known about the lived experience of mental health case managers.

Standard case management is in effect a residual category, defined by what it is not rather than by what it is. Our best indication as to what case managers do in their practice comes from a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation study (6), which showed that regardless of intention or design, case managers tend to focus their activity on direct clinical service provision. A clear need exists to develop means to reliably determine the nature and quantity of case manager activity and to be able to identify the impact of service structure and other variables on this activity.

Previous responses to this challenge have employed interview and case record review procedures (9) and observational techniques (10). These methods are time consuming and make it difficult to readily obtain sample sizes sufficient to enable investigation of variables affecting activity. They therefore result in studies that are informative but essentially descriptive.

Our aim was to develop a simple means of enabling case managers to tell us what kind of work they were doing and how well they thought they were performing. Our larger purpose was to identify and quantify factors such as caseload that might be expected to impinge on work type and work quality. The advantage of our approach was that it enabled us to access quite large datasets. The disadvantage was that it inevitably depended on self-report with its attendant problems of reliability and validity.

In this paper we report on the development of a measure of self-efficacy of case managers and its application in an investigation of caseload.

Methods

Subjects

The full sample consisted of 300 case managers working in metropolitan mental health services (72 percent) and regional mental health services (28 percent) in the states of Queensland, Victoria, New South Wales, and Western Australia. All public mental health services using a case management model were invited to participate. Participating services were asked to send a full list of all staff providing case management, and each staff member was mailed information about the study and the questionnaires. Fifty percent of those who were mailed questionnaires returned them.

In our experience a response rate of 50 percent is typical for mental health professionals in Australia. The final study sample was further reduced because some respondents did not provide sufficient information to enable calculation of caseload, and others were judged to be unlikely to be providing standard case management. Although we were unable to exclude the possibility of bias on some dimension relevant to the study, the study sample had demographic characteristics similar to those of the workforce as a whole. We think it unlikely that sample bias affected the key variable relationships that were the focus of the study.

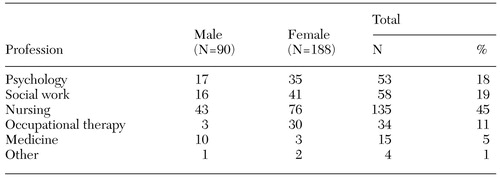

The median age of the 300 respondents was 39 years, and the median number of years of professional experience was ten. Table 1 shows the profession and gender of the subjects.

Instruments

Case managers were asked to respond to questions about their professional background, work setting, and workload. They also completed three scales, two of which were relevant to this study. The two scales were the General Health Questionnaire, 12-item form (GHQ-12), and the Case Manager Personal Efficacy Scale (CMPES).

GHQ-12 is a standardized index of general nonpsychotic psychological disturbance that has been used in a wide range of research and health screening applications and has well-established psychometric properties (11). Higher scores indicate increased psychological disturbance.

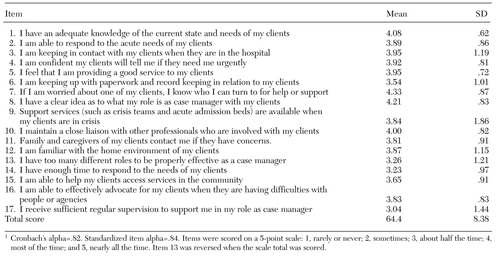

CMPES is a 17-item measure developed by the authors for this study. Higher scores on the CMPES indicate higher personal efficacy. Personal efficacy (self-efficacy) is a construct defined by Bandura (12) as the degree to which individuals consider themselves capable of performing a particular activity. It is a robust predictor of actual work performance (13).

Scale items from the CMPES are shown in Table 2. Items were loosely based on the 13 case manager activities described by Kanter (1), but they were also derived from role prescriptions contained in the Area Integrated Mental Health Service Standards (14) and policy documents issued by Victoria's Department of Health and Community Services. The activity statements were also consistent with empirical reports of activities of case managers and focused on generic roles rather than specific therapeutic activities. The activity statements were supplemented by key role support statements identified by case managers during development and pilot testing of the CMPES. Items were constructed in the form of personal efficacy statements in view of the substantial research literature showing that these kinds of statements are good predictors of actual workplace behavior (13).

The CMPES was pilot tested with a sample of 50 case managers, and one item was deleted because it detracted from the reliability of the scale. Five items, including the role support statements, were added in response to feedback from the pilot sample. The final scale comprised 13 role performance statements (items 1 to 6 and 10 to 16), three role support statements (items 7, 9, and 17), and one role comprehension statement (item 8). The results of the pilot test suggested that the scale was likely to have adequate internal consistency, which was confirmed when a reliability analysis was undertaken with the larger study sample of 300. The Cronbach alpha coefficient for the 291 respondents who checked all items was .82, suggesting acceptable internal consistency.

Determination of caseload

Subjects were asked how many clients constituted their caseload. They were also asked what proportion of full time they worked and what proportion of their job was devoted to case management. The adjusted caseload was derived by dividing the subject's total number of clients by the two time variables to express caseload in terms of a full-time worker providing case management as his or her sole service. For example, a half-time worker who has a caseload of 20 and spends 80 percent of the time providing case management will have an adjusted caseload of 50 (20 divided by .5 divided by .8).

This approach is a very simple means of determining caseload and does not take into account factors such as travelling time and the maturity of the caseload, which may have an impact on work capacity. However, it is a better estimate than the gross number of clients and provides a crude estimate that should be sufficient to determine whether any relationship exists between caseload and personal efficacy in the case manager role.

Twenty-two of the original sample of 300 did not provide enough information to enable calculation of adjusted caseload, and they were excluded from further analysis. We also excluded subjects who reported an adjusted caseload of less than five or greater than 79. Those with high adjusted caseloads were excluded on the grounds that they could not be providing standard case management. Those with very small caseloads were excluded on the grounds that either case management made up such a small part of their work as to make their reports unreliable or that they were not providing standard case management.

A total of 248 respondents from the original sample were included in the final sample. Adjusted caseloads ranged from 5.6 to 78. The mean± SD adjusted caseload was 34.9±17.7, the median was 33.3, and the mode was 40.

Results

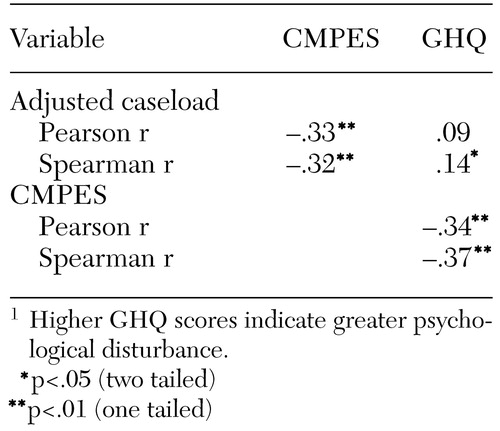

The relationship between caseload and GHQ and CMPES scores was investigated using both Pearson and Spearman correlations. Spearman correlation was used because distribution of adjusted caseload scores did not approximate normality. In view of the similarity of Spearman and Pearson coefficients, Pearson correlation was used in partial correlation analysis.

The strength and significance of relationships are displayed in Table 3, which shows that CMPES and GHQ scores had a moderate and highly significant relationship. Higher efficacy of case managers was associated with lower personal distress. CMPES scores had a similar strength and significance of relationship with adjusted caseload, such that higher caseloads were associated with lower efficacy scores. A weak but significant Spearman correlation was noted between adjusted caseload and GHQ scores, such that higher caseload was associated with increased personal distress.

To exclude the impact of other potential covariates on the relationship between adjusted caseload and score on the CMPES, a partial correlation analysis was performed controlling for age, gender, whether the subject worked in a metropolitan or rural service, GHQ score, and number of years of work in the profession. The covariates were found to have a minor impact on the relationship between adjusted caseload and CMPES scores, reducing the Pearson r coefficient to .31. If GHQ score was excluded, which might be reasonable in view of the uncertain causal directionality of the relationship between CMPES and GHQ scores, the Pearson r was unaffected by the partial correlation analysis.

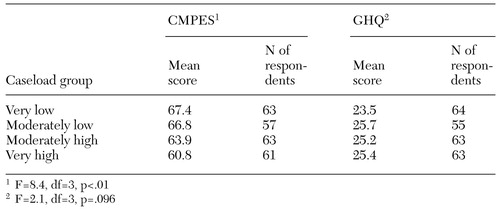

Given evidence of a general linear relationship between adjusted caseload and both CMPES and GHQ scores, we decided to investigate the nature of this relationship by dividing subjects into four groups according to quartile distribution of their adjusted caseload scores. The very-low-caseload group had an adjusted caseload of 5 to 20. For the moderately low group, the adjusted caseload was 21 to 33. For the moderately high group, it was 34 to 46. For the very-high-caseload group, it was 47 to 80.

One-way analysis of variance was performed to test for the significance of any differences in CMPES and GHQ scores for the four groups. Results of the analysis are shown in Table 4. Post hoc analysis, using a Bonferroni correction, of CMPES scores for the caseload groups revealed no significant differences between the two low-caseload groups or between the two high-caseload groups. However, both the low-caseload groups were significantly higher in personal efficacy (p<.01) than the very-high-caseload group, and the difference between the very-low-caseload group and the moderately high caseload group approached significance (p<.1).

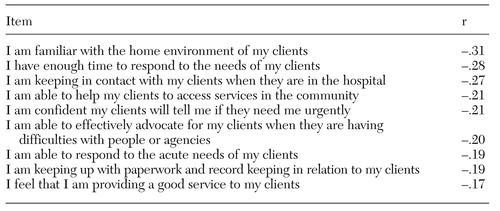

To evaluate the sensitivity of specific items on the CMPES to caseload size, Spearman correlations were performed between each item and adjusted caseload. Correlations were significant at the .01 level for nine of the 17 items. The nine items together with their Spearman correlation coefficients are presented in Table 5. All items were negatively associated with caseload, so that higher caseload was associated with reduced efficacy. Knowledge of clients' domestic environment was the item most sensitive to caseload, suggesting that home visiting was less likely to occur when caseloads were high. Other areas reported to be affected by caseload were acute response, hospital contact, and linkage and advocacy. Basic monitoring roles were less affected, but case managers' general sense of efficacy was significantly related to caseload.

Discussion and conclusions

The data presented here provide, to our knowledge, the first attempt to quantify the relationship between caseload and an indicator (in this case, personal efficacy) of case manager role performance. The means by which both caseload data and role performance information were collected necessitates caution in the interpretation of results. However, even the most cautious interpretation suggests that an inverse relationship exists between case managers' personal efficacy and caseload size. The relationship was independent of the personal characteristics of case managers, such as age, gender, experience, work setting, or GHQ scores. The strength of this relationship may well be underestimated in this study, given the difficulty in obtaining accurate and comparable information about caseloads.

Although correlation does not usually permit causal inference, in this case it might be reasonable to assume that higher caseloads result in lower personal efficacy. The alternative causal inference, that case managers with lower personal efficacy acquire higher caseloads, lacks face validity. It is possible that unassertive case managers with low efficacy become victims through unfair case assignment. However, the finding of a significant relationship between caseload and personal efficacy, independent of GHQ scores, lends weight to the proposition that personal efficacy indicates role performance and not just global self-perception. Furthermore, the specific items of case managers' efficacy most sensitive to caseload were those that are most likely to be affected by demands on time. Activities such as home visiting, visiting clients when they are in the hospital, and managing acute episodes are time consuming and require a degree of flexibility in work practice that is likely to be restricted by larger caseloads.

This study permitted evaluation of general trends and relationships with a substantial sample of case managers. However, achieving superior accuracy in measuring the relationship between caseload and case managers' role performance requires a different kind of study, involving a more exact determination of the time each worker has for clinical case management and observation of actual clinical activity. Although self-efficacy is a useful means of estimating work performance, its criterion validity weakens as tasks become more complex and when actual workplace settings rather than experimental settings are involved (13). The results obtained in this study suggest that a smaller study designed to achieve measurement accuracy and criterion validity is warranted.

Given the potential measurement error, we cannot make recommendations about the optimal size of a caseload. Further, optimal caseload must be judged both in light of tasks that case managers are expected to perform and in relation to the proportion of their workload allocated to case management. Although we have demonstrated that self-efficacy in certain roles or tasks is affected by caseload size, whether or not this presents a problem for service delivery will depend on the importance of the task or role in the achievement of service goals.

Notwithstanding these reasons for caution, it was notable that the difference in CMPES scores between case managers with very low and moderately low caseloads was small and nonsignificant, whereas a more substantial and significant decline in total personal efficacy was noted between case managers with moderately low and moderately high caseloads. In this study, the median adjusted caseload of 33 was equivalent to an actual caseload for a full-time case manager of 18 clients. This suggests that in the Australian service context, for the range of tasks and roles measured by this scale, optimal personal efficacy can be achieved with actual client loads in the range of 15 to 20.

The reason for the difference between adjusted and actual caseloads is that the case managers, on average, assigned just under half their working time to a range of non-case-management duties, which included intake and extended-hours crisis work, living skills groups, specialist individual therapy during depot clinics or psychotherapy on referral, and a variety of community development, education, and liaison roles. When such services are provided through specialist personnel, the proportion of a case manager's time allocated to case management can be expected to increase, and we would anticipate that actual caseloads could be higher without major loss of personal efficacy.

Dr. King is affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of Queensland in Australia. Dr. Le Bas is with the department of psychological medicine at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. Mr. Spooner is with Norwich Health Services Trust in the United Kingdom. Address correspondence to Dr. King at the University of Queensland, K-Floor, Mental Health Centre, Royal Brisbane Hospital, Queensland 4029, Australia (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Profession and gender of case managers in the sample

|

Table 2. Mean±SD scores of a sample of 291 case managers on the Case Manager Personal Efficacy Scale1

|

Table 3. Relationship between adjusted caseload and scores on the Case Manager Personal Efficacy Scale (CMPES) and the General Health Questionaire, 12-item form (GHQ)1

|

Table 4. Analysis of variance in respondents' scores on the Case Manager Personal Efficacy Scale (CMPES) and the General Health Questionaire, 12-item form (GHQ), for the four adjusted-caseload groups

|

Table 5. Spearman correlations between item scores on the Case Manager Personal Efficacy Scale and adjusted caseload for items most sensitive to changes in caseload

1. Kanter J: Clinical case management: definition, principles, components. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:361-368, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Shepherd G, Muijen M, Hadley T, et al: Effects of mental health services reform on clinical practice in the United Kingdom. Psychiatric Services 47:1351-1355, 1996Link, Google Scholar

3. Allness D: The Program of Assertive Community Treatment (PACT): the model and its replication. New Directions in Mental Health Services, no 74:17-26, 1997Google Scholar

4. Mueser K, Bond G, Drake R, et al: Models of community care for severe mental illness: a review of research on case management. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:37-74, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Sledge W, Astrachan B, Thompson K, et al: Case management in psychiatry: an analysis of tasks. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:1259-1265, 1995Link, Google Scholar

6. Ridgely M, Morrissey J, Paulson R, et al: Characteristics and activities of case managers in the RWJ Foundation Program on Chronic Mental Illness. Psychiatric Services 47:737-743, 1996Link, Google Scholar

7. Hromco J, Lyons J, Nikkel R: Styles of case management: the philosophy and practice of case managers. Community Mental Health Journal 33:415-428, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Marshall M: Case management: a dubious practice. British Medical Journal 312:523-524, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Hargreaves W, Shaw R, Shadoan R, et al: Measuring case management activity. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 172:296-300, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Waite A, Carson J, Cullen D, et al: Case management: a week in the life of a clinical case management team. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 4:287-294, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Goldberg D, Gater R, Sartorius N, et al: The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychological Medicine 27:191-197, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Bandura A: Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educational Psychologist 28:117-148, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Stajkovic A, Luthans F: Self-efficacy and work-related performance: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 124:240-261, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Rosen A, Parker G, Miller V: Area Integrated Mental Health Service Standards, 3rd ed. Chatswood, New South Wales, Area Integrated Mental Health Services Project, 1995Google Scholar