Gambling Behavior of Louisiana Students in Grades 6 Through 12

Abstract

Objectives: The prevalence of problem and gambling behavior, the average age of onset of gambling behavior, and the co-occurrence of gambling disorder with substance use were determined in the Louisiana student population grades 6 through 12. METHODS: A stratified randomized sample of 12,066 students in Louisiana schools during the 1996–1997 school year was surveyed about gambling behavior using the South Oaks Gambling Screen—Revised for Adolescents (SOGS-RA). RESULTS: Fourteen percent of the students never gambled, 70.1 percent gambled without problems, 10.1 percent indicated problem gambling in the past year (level 2 according to the SOGS-RA), and 5.8 percent indicated pathological gambling behavior in the past year (level 3). Weekly or more frequent lottery play was reported by 16.5 percent. The average age of onset of gambling behavior was 11.2 years. Fifty-nine percent of the students with problem and pathological gambling behavior reported frequent alcohol and illicit drug use. CONCLUSIONS: A significant minority of Louisiana students in grades 6 through 12—15.9 percent—acknowledged gambling-related symptoms and life problems. The association of problem and pathological gambling with use of alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana provides preliminary support for the inclusion of gambling among other adolescent risk behaviors.

Louisiana, along with 46 other states, has participated in the expansion of legalized gaming that has occurred over the past 20 years. Gaming is very accessible in Louisiana; gambling opportunities include pari-mutuel racing, off-track betting, charitable gaming, lottery, video-poker machines, and riverboat and Indian-casino gambling. In 1996 one gaming license existed for every 605 Louisiana adults (1).

Although adolescents predominantly gamble on unlicensed forms of gambling, such as playing cards or pool for money, illegal underage participation in legalized gaming activities is significant (2). Seven studies from four different areas—Massachusetts (3,4), Illinois (5,6), Minnesota (7) and Alberta, Canada, (8,9)—found underage participation in legalized gaming, especially lotteries.

DSM-IV defines pathological gambling as an impulse control disorder. Pathological gambling resembles dependence on a physical substance, and symptoms are consistent with tolerance, withdrawal, relief use, preoccupation, efforts to control or discontinue, and significant social and occupational consequences (10). Problem gambling is usually defined as gambling that causes some detrimental effects on the gambler's work, social, financial, or family life but not to the extent of pathological gambling (11).

A recent meta-analysis of the prevalence of adolescent gambling disorders included 14 studies done between 1987 and 1997 in four provinces in Canada and eight states in the United States, with approximately 19,000 total subjects (2). The estimated prevalence of problem gambling was 14.8 percent (95 percent confidence interval=9 to 20.7 percent). The estimated prevalence of pathological gambling was 5.8 percent (CI=3.2 to 8.4 percent).

The objectives of this study were to determine the prevalence of problem and pathological gambling behavior, the average age of onset of gambling behavior, and the co-occurrence of gambling disorder with substance use in the Louisiana student population in grades 6 through 12.

Methods

The anticipated sample, consisting of 15,575 students, represented 3.5 percent of 445,000 registered students in grades 6 through 12 in public and nonpublic schools, based on the 1996–1997 Louisiana School Directory (12). Classrooms in each grade were randomly selected by matching the last two digits of the classroom's school code (13) with the first two digits on a table of random numbers. A total of 698 classrooms were identified among 585 schools in Louisiana's 64 parishes.

Approval for study participation was obtained from parish school superintendents and private school principals from 57 of 64 parishes, representing 565 classrooms in 470 schools. Parish superintendents were asked to supply the name of the teacher with the most years of experience and the estimated number of students within the identified classroom or classrooms. Questionnaires were included in survey packets that contained instructions on administration under test-taking conditions, and the packets were mailed to the identified teachers.

Student participants completed the South Oaks Gambling Screen—Revised for Adolescents (SOGS-RA) (14). The SOGS-RA is an objective questionnaire with 12 scored items that measures gambling frequency and gambling-associated behaviors based on the definition of pathological gambling. The items address being preoccupied with gambling, experiencing interference of gambling with school and home activities, returning to gamble to cover previous losses, lying to conceal losses or evidence of gambling, spending escalating amounts of money and time gambling, arguing with family members over gambling, borrowing money to gamble or cover gambling debts, feeling guilty about gambling, and experiencing an inability to stop gambling.

SOGS-RA scores of 0 or 1 indicate level 1 gambling—the person has no problem with gambling. Scores of 2 or 3, or level 2 gambling, indicate that the person is at risk for problem gambling, and scores of 4 and higher, level 3, indicate that the person is at risk for pathological gambling behavior (2,14). In addition to the scored items, the SOGS-RA measures the frequency of participation in 17 different gambling activities. The SOGS-RA has a reliability estimate of .80. Construct validity has been demonstrated by correlation with probability less than .01 with lifetime gambling participation, past-year gambling, and the amount gambled in the past year (14). For this study, questions about demographic characteristics and alcohol, nicotine, and drug use were added to the core instrument.

A total of 12,066 questionnaires were returned and hand-coded with appropriate school and parish codes. Quality control measures removed 330 surveys, leaving 11,736 for statistical analyses.

Confidence intervals, ranges within which there is a 95 percent probability of capturing the true value of the mean, were calculated for population estimates, using either a maximal error of tolerance for means or a maximal (or margin of) error for proportions. Chi square analyses were performed on discrete categorical data. One-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used when continuous responses were compared by categories along a single dimension. The significance level was set at .05. Chi square analyses and ANOVAs were performed using Minitab (15).

Multivariate analysis, using SPSS, was used to identify independent variables predicting SOGS-RA classification. Stepwise discriminant function analysis (p<.05 to enter and p>.10 to remove) was selected to produce two functions that would separate the three levels of gambling behavior. The SOGS-RA level was the criterion variable and 13 factors such as gender, ethnic affiliation, substance use, and after-school activity were the independent variables. Function 1 separated level 1 gambling from levels 2 and 3. Function 2 separated level 2 from level 3.

Age and grade were not included among the independent variables because they were highly correlated (r=.93), and the plot pattern of level 2 and 3 gamblers appeared curvilinear over age and grade due to dropout at higher grade levels.

Results

Of the 11,736 respondents, 53.4 percent were female and 46.5 percent were male. Eighty-six percent were in public schools and 14 percent in private schools. Caucasians represented 53.7 percent of the sample, African Americans 34.4 percent, Native Americans 2.3 percent, Hispanics 2.2 percent, and Asians 1.8 percent; 5.1 percent were in a category "other."

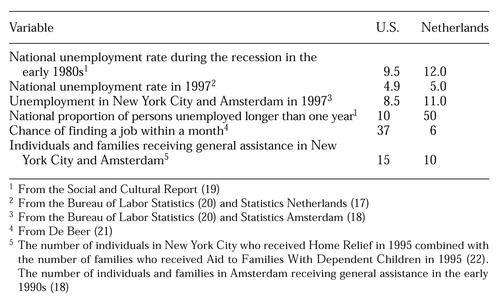

The Louisiana students in the study engaged in a wide variety of licensed and unlicensed gambling activities. Lifetime and past-year participation were highest for lottery, card playing, sports betting, games of personal skill, and dice games. Table 1 provides data on lifetime prevalence rates for 17 gambling activities.

The majority of students gambled infrequently. The monthly-or-less participation rates for the eight most frequent activities ranged from 83.5 percent to 95 percent. A minority of students gambled very frequently. Weekly-or-more participation rates were 16.5 percent for scratch-off lottery, 12.5 percent for sports betting, 10.5 percent for cards, 10 percent for betting on games of skill, 9.4 percent for lotto, 8.9 percent for dice, 5.2 percent for video poker, and 5 percent for bingo. Half of the most frequent activities are licensed activities, and for the majority of students surveyed, participation in licensed activities is illegal due to age restrictions.

A minority of students acknowledged a variety of family, school, financial, and legal problems related to gambling. Family problems included arguments over gambling (8.7 percent), stealing from family members to gamble (4.1 percent), and falling out with family members over gambling (2.1 percent). School problems included using school lunch or bus money to gamble (8.5 percent), skipping school to gamble (3.5 percent), and skipping more than five times in the past year to gamble (1.9 percent). Legal problems included stealing to gamble (4.8 percent), stealing from sources outside the family to gamble (2.8 percent), and gambling-related arrests (1.5 percent). Serious financial problems because of gambling were acknowledged by 6.2 percent of the respondents.

Levels of gambling behavior were assigned by SOGS-RA scores, which summed acknowledged life problems and other symptomatic behaviors such as lying about gambling, chasing losses, and increasing amounts gambled. Fourteen percent of the sample had never gambled. The majority of the sample (70.1 percent) gambled without problems (level 1). Level 2 problem gambling was found for 10.1 percent (CI=9.6 percent to 10.6 percent), and level 3 pathological gambling was found for 5.8 percent (CI=5.3 percent to 6.1 percent). The distribution of level 2 and 3 gambling by grade ranged from 11 percent in grade 11 to 19.9 percent in grades 7 and 8.

The prevalence of gambling disorder varied by gender, ethnic affiliation, age, and school affiliation. Significantly more males than females indicated level 2 problem gambling (12.75 percent versus 7.8 percent; χ2=322.77, df= 2, p<.001). Significantly more males than females reported level 3 pathological gambling (9.2 percent versus 3 percent; χ2=14.9, df=2, p<.001).

Compared with students who attended private schools, those who attended public schools showed significantly higher rates of problem and pathological gambling behaviors (χ2= 14.9, df=2, p<.01). Rates of levels 2 and 3 gambling among public school students were 10.1 percent and 6 percent, respectively. These rates were 9.7 percent and 4.3 percent, respectively, among private school students.

Level 3 pathological gambling varied by ethnic affiliation (χ2=105.69, df=10, p<.01). Level 3 gambling occurred more frequently among minorities and less frequently among Caucasians. The prevalence rates of pathological gambling were 9.4 percent for Hispanics, 7.8 percent for Asians, 7.7 percent for African Americans, 6.5 percent for Native Americans, 6.2 percent for the "other" category, and 5.6 percent for Caucasians.

Gambling disorder co-occurred with substance use. Fifty-nine percent of students with problem and pathological gambling drank alcohol or used illicit drugs weekly or more frequently.

Among the respondents, gambling behavior usually preceded smoking tobacco and use of marijuana and alcohol. The mean age of onset was 11.2 years for gambling behavior, 11.3 years for alcohol consumption, 11.6 years for smoking, and 13.2 years for marijuana use. A one-way ANOVA analyzing the relationship of age of onset and gender indicated that males had a significantly earlier age of onset of these activities than females (for gambling, F=22.28, df=1, 7,465, p<.001; for alcohol use, F=169.89, df=1, 7,318, p<.001; for tobacco, F=114.67, df=1, 6,157, p<.001; and for marijuana use, F=77.72, df=1, 3,142, p<.001).

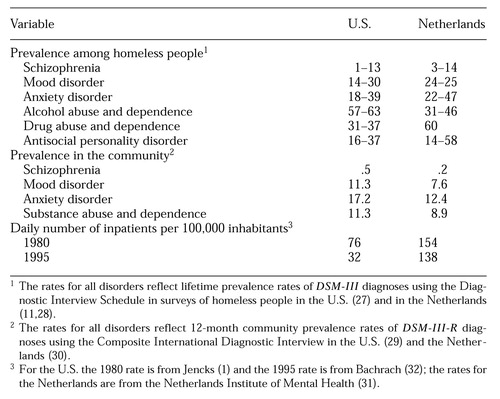

Discriminant function analysis yielded one significant function that separated level 1 from level 2 and 3 gambling. As Table 2 shows, function 1 indicated that problem and pathological gamblers (levels 2 and 3) were more likely to use illicit drugs, drink alcohol to intoxication monthly or more frequently, smoke tobacco and marijuana, and be male, African American, and non-Caucasian. Lifetime prevalence of marijuana and tobacco use, past-year prevalence of alcohol and other drug use, and alcohol use monthly or more frequently accounted for 12.2 percent of the variance between level 1 gamblers and level 2 and 3 gamblers. Substance use factors could identify students who might develop gambling problems but could not separate level 2 and 3 gambling.

Function 2, parental gambling, only weakly separated level 2 from level 3 gambling. Parental gambling in this analysis seemed to have a weak protective effect on the severity of a student's gambling disorder.

Discussion and conclusions

The findings of an early onset and wide range of gambling behavior among the students in this study and the infrequent participation in gambling and lack of adverse consequences for the majority of students who gambled (70.1 percent) indicate that some gambling may be normative for this age group. School-based primary prevention programs, whose goal is to delay onset of gambling, may not be appropriate for preventing problem and pathological gambling. A harm-reduction model that informs students about the risks and symptoms of problem and pathological gambling and about treatment resources may be more appropriate.

A minority of the students in the sample—15.9 percent—acknowledged gambling-related symptoms and life problems. The prevalence of problem and pathological gambling among the students is consistent with national estimates (2,16). Significant participation by students in licensed gaming activities, especially lotteries, is also consistent with studies in other geographic areas (3,4,5,6,7,8,9).

The gender and ethnic risk factors found in this study are consistent with adult prevalence surveys in New Jersey, New York, Maryland, and Massachusetts (17) and in Louisiana (18), which found that minority males were more likely to be identified as pathological gamblers.

Although prevalence rates of gambling disorder have been established and some risk factors identified, the significance of adolescent gambling is unknown. A recent review noted that no longitudinal studies of adolescent gambling exist (19). The persistence of problem and pathological gambling into adulthood and its effect on development and adult functioning is unknown.

Another approach to understanding problem and pathological gambling is its relationship to more intensely studied adolescent behaviors. The theory of adolescent risk behavior (20), an extension of the problem-behavior syndrome (21), hypothesizes that several behaviors are positively correlated among adolescents, including use of tobacco, alcohol, and drugs; unsafe sex; nonuse of seat belts; and delinquent behavior. All of the risk behaviors are also negatively correlated with conventional behaviors such as church attendance and academic achievement.

Limitations of this study include an 81 percent response rate based on the classrooms selected in the randomized sample, lack of a clinical interview to validate problem or pathological gambling, and use of self-report data on substance use.

The study found that the majority of students with problem and pathological gambling used alcohol and other illicit drugs frequently. The discriminative function analysis found that problem and pathological gambling correlated with all the risk behaviors that were assessed in this study—use of tobacco, marijuana, alcohol, and drugs. The positive correlation with the use of alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and other drugs as a group provides preliminary support for the inclusion of problem and pathological gambling as an adolescent risk behavior.

The association of gambling disorder with other risk behaviors also suggests a prevention approach. Assessment for problem and pathological gambling could be included in assessments of adolescent populations with a high prevalence of other risk behaviors, such as delinquent youths and those who are chemically dependent. Providing gambling disorder treatment to identified patients in these populations as a complement to the primary treatment may be a cost-effective approach to secondary prevention of gambling disorders.

Acknowledgments

The study was made possible by the Office of Alcohol and Drug Abuse of the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals (contract 62133). The authors thank the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals and the Louisiana Department of Education for supporting this study.

Dr. Westphal is professor of clinical psychiatry and Dr. Rush and Dr. Stevens are assistant professors of psychiatry in the department of psychiatry at Louisiana State University Medical Center, 1501 Kings Highway, P.O. Box 33932, Shreveport, Louisiana 71130 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Johnson is assistant professor of psychology at Centenary College of Louisiana in Shreveport. This paper was presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association held May 31 to June 4, 1998, in Toronto.

|

Table 1. Self-reported lifetime participation in licensed and unlicensed gambling activities among 11,736 Louisiana students in grades 6 through 12

|

Table 2. Correlations between the two discriminant functions and eight variables that discriminated problem and pathological gambling from nonproblem gambling among 11,736 Louisiana students in grades 6 through 121

1. Westphal JR, Rush JA: Pathological gambling in Louisiana: an epidemiological perspective. Journal of the Louisiana State Medical Society 148:353-358, 1996 Medline, Google Scholar

2. Shaffer HJ, Hall MN: Estimating the prevalence of adolescent gambling disorders: a quantitative synthesis and guide toward standard gambling nomenclature. Journal of Gambling Studies 12:193-214, 1996 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Shaffer HJ: The Emergence of Youthful Addiction: The Prevalence of Underage Lottery Use and the Impact of Gambling. Technical Report 121393-100. Boston, Massachusetts Council on Compulsive Gambling, 1993Google Scholar

4. Health and Addictions Research, Inc: Adolescent Substance Use in Massachusetts: Trend Among Public School Students. Boston, Massachusetts Department of Public Health, 1997Google Scholar

5. Radecki TE: The sales of lottery tickets to minors in Illinois. Journal of Gambling Studies 10:213-218, 1994 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Jones M: Confronting the player problem. International Wagering and Business Magazine 18(12):58-68, 1997 Google Scholar

7. Winters KC, Stinchfield RD, Kim LG: Monitoring adolescent gambling in Minnesota. Journal of Gambling Studies 11:165-183, 1995 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Gambling and Problem Gambling in Alberta. Report prepared for Alberta Lotteries and Gaming. Edmonton, Alberta, Wynne Resources, Ltd, 1994Google Scholar

9. Adolescent Gambling and Problem Gambling in Alberta. Edmonton, Alberta Alcohol and Drug Abuse Commission and Wynne Resources, Ltd, 1996Google Scholar

10. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

11. Lesuir HR: Costs and treatment of pathological gambling. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 556:153-171, 1998 Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Louisiana 1996-1997 School Directory. Baton Rouge, Louisiana Department of Education, Bureau of School Accountability, Office of Research and Development, 1997Google Scholar

13. Louisiana Annual Financial and Statistical Report, 1995-1996. Bulletin 1472. Baton Rouge, Louisiana Department of Education, Office of Management and Finance, Division of Planning, Analysis, and Information Resources, 1996Google Scholar

14. Winters KC, Stinchfield RD, Fulkerson J: Toward the development of an adolescent gambling problem scale. Journal of Gambling Studies 9:63-84, 1993 Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Minitab Statistical Software, release 11.2. State College, Penn, Minitab, Inc, 1996Google Scholar

16. Shaffer HJ, Hall MN, Vander Bilt J: Estimating the Prevalence of Disordered Gambling Behavior in the United States and Canada: A Meta-Analysis. Boston, Harvard Medical School, Division of Addiction, Dec 10, 1997Google Scholar

17. Volberg RA: The prevalence and demographics of pathological gambling: implications for public health. American Journal of Public Health 84:237-241, 1994 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Volberg RA: Wagering and Problem Wagering in Louisiana: Report to the Louisiana Economic Development and Gaming Corp. Roaring Spring, Penn, Gemini Research, 1995Google Scholar

19. Stinchfield R, Winters KC: Gambling and problem gambling among youths. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 556:172-185, 1998 Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Jessor R: New Perspectives on Adolescent Risk Behavior. New York, Cambridge University Press, 1998Google Scholar

21. Jessor R, Jessor SL: Problem Behavior and Psychosocial Development: A Longitudinal Study of Youth. New York, Academic Press, 1977Google Scholar