Similarities and Differences in Homelessness in Amsterdam and New York City

Abstract

Differences and similarities in homelessness in Amsterdam and New York City were examined, particularly in regard to persons most at risk for homelessness—those with mental illness and with substance abuse problems. The Netherlands is a welfare state where rents are controlled by the national government and more than half of the housing is public housing. Virtually all homeless people in Amsterdam are unemployed and receive some sort of social security benefit. Direct comparisons of the results of American and Dutch studies on homelessness are impossible, mainly because the estimates are uncertain. Because of the Dutch welfare system, Amsterdam has a smaller proportion of homeless people than New York City, although more people are homeless in Amsterdam today than 15 years ago. Neither a lack of affordable housing or sufficient income nor unemployment has been a direct cause of the increase of homelessness. As in New York City, many of the homeless in Amsterdam are mentally ill or have substance use disorders. The increase in the number of homeless people in Amsterdam consists largely of mentally ill people who would have been admitted to a mental hospital 20 years ago and of older, long-term heroin abusers who can no longer live independently. Thus institutional factors such as fragmentation of services and lack of community programs for difficult-to-serve people are a likely explanation for the growing number of homeless people in Amsterdam.

Homelessness is often thought to be rare in countries with a superior safety net (1). However, this is not the case. In the Netherlands, which is a welfare state, the number of homeless people was estimated at 20,000 in 1995 (2). This point prevalence estimate of .13 percent of the Dutch population is similar to some of the lower estimates of the number of homeless people in the United States (1,3,4,5).

Amsterdam has never had large, warehouse-style shelters. Fifteen years ago only two types of services for homeless people in Amsterdam existed: long-term shelters for older homeless people who mostly had alcohol abuse problems and emergency shelters where homeless people were allowed to sleep for five nights a month. Both types of services still exist.

Present public policies aimed at ending homelessness in Amsterdam are often based on the results of American research. Many service programs for the homeless in Amsterdam have been borrowed from successful programs in New York City. For example, the implementation of separate housing programs for homeless persons with mental illness and proactive outreach was a result of experiences of service providers in Amsterdam supported by research conducted in the United States. As a consequence, development of new services for the homeless population in Amsterdam and New York City is very similar in its small-scale approach, with an emphasis on transitional housing and specialized care for such problems as mental illness and substance abuse.

Whereas new specific services addressing the needs of the homeless may be very similar in the two countries, the overall social context is certainly not similar, nor, probably, are the causes of homelessness. The goal of this study was to examine the similarities and differences in homelessness in Amsterdam and New York City. First, a rough sketch of the Dutch social context is given, comparing the housing situation, unemployment, and the social security system in the Netherlands and in the United States. Second, the Dutch approach of developing services for specific groups of individuals who are most at risk of becoming homeless, such as mentally ill persons and individuals with substance abuse problems, is described.

Definitions and numbers

In the Netherlands the definition of homelessness (2) is identical to the narrow definition of homelessness used in the United States (6) and comprises people who live on the street or reside in shelters. As in the United States, in the Netherlands the number of homeless people is relatively higher in large cities. In Amsterdam the number of homeless individuals was estimated to be between 2,000 (7) and 6,550 (8) in 1990, which is two to five times the national average. The number of homeless people in New York City was estimated to be between 70,000 and 90,000 in the early 1990s (6), which is six to eight times higher than the national rate.

A study by Cohen (6) found that approximately 50 percent of homeless people in New York City lived on the street, compared with around 10 percent in Amsterdam (9). Furthermore, Cohen reported that roughly a third of the homeless population of New York City were young adults, a fifth were homeless families, and 90 percent of the shelter population were members of ethnic minority groups. Of the Amsterdam homeless population, around 10 percent were young adults (10,11), less than 10 percent were women with children, and 40 percent were members of an ethnic minority group (10).

It is impossible to compare the varying results of American research with the results of the few Dutch studies on homelessness, mainly because considerable uncertainty surrounds the estimates reported. Certainly, it is hard to believe that the prevalence of homelessness is about as high in Amsterdam as it is in New York City. The point prevalence method of estimating may obscure differences between the homeless situation in the two countries, because it does not take into account the many people who are homeless for a short period of time, and it overrepresents chronic long-term homeless people.

The results of two surveys in the U.S. revealed a high turnover in the homeless population. A national telephone survey reported a five-year prevalence of literal homelessness of 3.6 percent (12), and a study of shelter admission rates in Philadelphia and New York City reported that, over five years, 3.27 percent of New York City's population spent time in a public shelter (4).

No comparable period prevalence estimates of homelessness exist for the Netherlands. However, European research on homelessness supports the idea that the homeless population in European countries consists almost exclusively of people with multiple problems who are chronically homeless and that this homeless population is relatively smaller than that in the United States (13,14). A study of a sample of 180 homeless individuals recruited at emergency shelters and drop-in centers in Amsterdam found that 60 percent of the respondents had been homeless for more than one year (9). A representative sample taken from all service locations, including long-stay shelters, would certainly have found a higher rate.

The social context

The shortage of affordable housing is an important cause of the increase in homelessness in the United States. However, no agreement exists about whether the housing market has generated a direct or only an indirect effect. Some argue that urban revitalization and gentrification brought about a tighter rental market, while others assert that it was a process with interacting factors, such as long-term joblessness and lagging government benefits. Nevertheless, it is generally agreed that more people became homeless because their decreased income was too small to pay the increased rent (1,3,15,16). The almost complete demolition of flophouses or cubicle hotels also led people to homelessness, whether directly as a result of eviction (15) or indirectly through increased prices (1).

The housing market in the Netherlands is very unlike that in the United States. To a large extent, the Dutch rental housing market is a nonprofit system, funded by the national government and aimed at the socially fair distribution of available housing. Rents are controlled by the national government. Nevertheless, in the 1980s housing rents increased almost twice as much as the general price index (47 percent versus 25 percent) (17). More than half of the total housing stock in Amsterdam is public housing (18). The quality of public housing is good, and housing assistance helps low-income residents pay the rent.

In the 1970s the national government stimulated urban renewal programs. The first goal of these programs was to improve the quality of houses, but since the early 1980s local authorities have also tried to create a more mixed housing stock, mixing privately owned homes and public housing in the same neighborhood and locating expensive houses next to low-cost housing.

Usually, urban redevelopment in Amsterdam did not permanently evict residents. Tenants had the opportunity to return to their homes after the renewal of the neighborhood. Although the higher quality of the houses led to increased rents, tenants were able to pay the higher rent because of the national rent-subsidy program. Housing policies of the national government and the local authorities did not have any effect on the shortage of housing in the 1980s. In Amsterdam the number of individuals and families who were classified by housing associations and local authorities as most urgently in need of housing fluctuated between 50,000 and 60,000 applicants in the 1980s and declined to 43,000 applicants in the early 1990s (18). Only a few applicants for housing are homeless. Most are families who want better housing or individuals who want to start living independently.

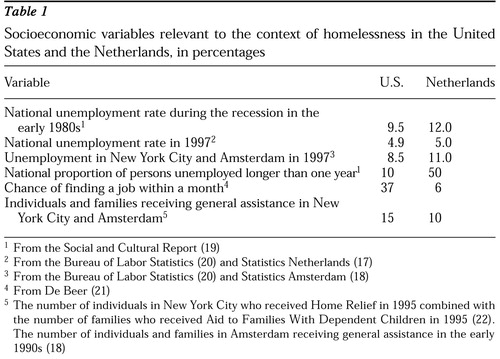

Virtually all homeless people in Amsterdam are unemployed and receive some sort of social security benefit (10). Table 1 presents data from several sources on socioeconomic variables relevant to homelessness (17,18,19,20,21,22). In the early 1980s the unemployment rate in both the Netherlands and the United States increased dramatically. In the same period, safety-net programs in both countries changed significantly. The Reagan administration tightened eligibility for federal entitlements, and eligibility for other safety-net programs, such as food stamps and federal housing assistance, also changed (3,23). For many in the U.S., declining wages and the declining value and availability of public assistance put housing out of reach (15).

In the Netherlands, the social security system has also changed in the last ten to 15 years (19). In the early 1980s, the national government tried to lower expenditures on social security by freezing the level of individual benefits. However, mainly because of rising unemployment and the growing number of people eligible for disability benefits, the costs of the social security system still rapidly increased. Therefore, the national government changed its policy in the late 1980s and early 1990s—instead of lowering the level of benefits again, it restricted eligibility for unemployment benefits, disability benefits, and early-retirement settlements. As a result of this volume policy, relatively more people became dependent on the lower general assistance payments from their municipality.

The level of general assistance payments, which is slightly lower than the legal minimum wage, is considered the social minimum in the Netherlands. Every legal resident in the Netherlands who has no income is eligible for general assistance. Parallel to the strong increase in unemployment, the number of individuals and families receiving such assistance in Amsterdam increased sharply in the early 1980s. More than 80,000 individuals and families in Amsterdam—11.5 percent of the city's population—received general assistance in 1984 (18). After 1984 the number of recipients declined slightly but remained high at around 10 percent, despite the end of the economic recession and an increasing number of new jobs. The continued elevation in the number of people receiving general assistance was an effect of high, long-term employment in Amsterdam and of the volume policy of the national government.

General assistance payments in Amsterdam, in combination with a rent subsidy, are enough to ensure a decent standard of living for most recipients, whereas in the United States general assistance benefits and payments from Aid to Families With Dependent Children are often not enough to pay the rent (24). When in the 1980s the Dutch national government cut social security benefits and housing rents increased, the expenditure on tenant-based rent assistance more than doubled, from 629 million Dutch guilders in 1980 to 1,473 million in 1988 (17). The rent subsidy made it possible for residents with a low income to keep paying their rent.

Vulnerability to homelessness

Among the poor, those with mental illness and substance abusers are the most vulnerable to homelessness (23,25). In addition, they may find it more difficult to arrange informal, makeshift housing (26). The literature on contemporary homelessness in the United States often includes estimates of the prevalence of mental illness and substance abuse among the homeless. The reported results of surveys vary greatly because of differences in definitions of mental illness and in survey methods (27).

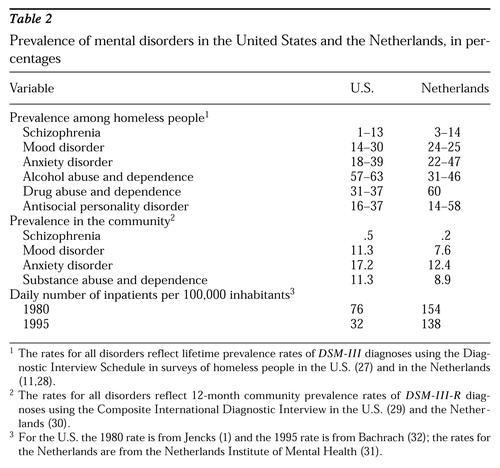

Few studies of mental illness and homelessness are available in the Netherlands. Only two surveys reported DSM-III prevalence rates of mental disorder obtained by structured interviews (11,28). Both surveys were conducted in Amsterdam. Table 2 presents the results of these two surveys and compares them with results from American surveys (27).

Table 2 also shows that comparable community surveys found higher prevalence rates of mental disorders in American households than in Dutch households (28,29,30,31) but that, proportionally, more people are hospitalized in mental hospitals in the Netherlands than in the United States (32,33). Although the restructuring of mental health care in the Netherlands did not involve a large reduction in mental hospital populations, it did result in a decline in length of stay (31), a decrease in first admissions (34), and a doubling of the number of readmissions (35). In other words, the function of the mental hospital as a stable residential environment for persons with chronic mental illness has disappeared in the Netherlands, as it has in the United States.

Redevelopment of old-style mental hospitals into community-based care and the corresponding shift in treatment policies did not lead to large numbers of hospitalized chronic mentally ill people becoming homeless in Amsterdam; however, it probably had an indirect effect. Many of the mentally ill homeless population of today would have been admitted to a mental hospital ten or 20 years ago. Now hospitals discharge individuals with severe mental disorders after a short stay, often without arranging for continuity of care in a community setting. As observed in the United States (36), this practice may lead to exacerbation of symptoms and homelessness.

According to Jencks (1), abuse of crack cocaine was one of the major causes of increasing homelessness in the United States. In Amsterdam, the problem of hard drug abuse is mainly one of heroin. Crack was not used by many people in Amsterdam in the 1980s, but since the early 1990s, crack has become popular as a secondary drug with most heroin users. The number of heroin abusers in the Netherlands in 1995 was estimated at 25,000 to 27,000 individuals (37). Of these heroin abusers, 6,300 live in Amsterdam. It is mainly an older cohort of people who started using heroin 15 to 20 years ago.

Since the mid-1970s, harm reduction has been at the core of the Dutch drug policy. It is directed not only at abstinence but also at regulation of the addiction if abstinence is not yet attainable. Among heroin abusers in Amsterdam, the number of fatal overdoses and the incidence of HIV are lower than in cities in other countries (38,39). As a consequence, and because there are very few new young users, the average age of a heroin abuser in the Netherlands increased in 1997 to 38.7 years. In recent years the use of shelters by these "veteran" drug abusers has increased because they are less and less capable of living without professional support, especially long-term shelter with in-house medical care and methadone dispensation.

Discussion and conclusions

Cultural differences underlie the structural differences and contrasting public policies in New York City and Amsterdam. Ideas about profit making, solidarity, government regulation, and individual freedom rule how a society and its citizens define the problem of homelessness and its solutions. Comparing the varying results of American research with the results of the few Dutch studies on homelessness is difficult, mainly because of the considerable uncertainty about the estimates reported. However, several differences and similarities can be observed.

First, relatively more people experience homelessness in New York City than in Amsterdam. Point prevalence estimates obscure an important difference: in the Netherlands the homeless population consists almost exclusively of people with multiple problems who are chronically homeless, whereas the United States has a high turnover in the homeless population, which is also more heterogeneous than the Dutch homeless population.

Second, not as many people become homeless in Amsterdam as in New York City because of the Dutch welfare system. The Dutch social security system is not as good as it was in the 1970s because, as in the United States, eligibility for national benefits has been tightened. However, for many people it still ensures a decent standard of living. Neither unemployment nor poverty are a likely explanation of the increase of homelessness in Amsterdam, especially because of the housing assistance program of the national government, which can be seen as the ultimate safety net for preventing homelessness in Amsterdam. However, the high unemployment rate, along with the fact that very few low-skill jobs exist in Amsterdam compared with New York City, is probably one of the reasons why rehabilitation is difficult, and therefore one of the reasons why homelessness is a chronic condition for many homeless individuals in Amsterdam.

Third, as in New York City, many of the homeless in Amsterdam are mentally ill or have a substance abuse problem, or both. Even though Amsterdam has a good safety net, there are more homeless people there today than 15 years ago. Such institutional factors as the fragmentation of mental health services, poor interagency cooperation, and the lack of community programs for difficult-to-serve individuals are a likely explanation of the increase of homelessness in Amsterdam. The Dutch safety net is not sufficient to prevent the most vulnerable from becoming homeless. To a large extent, the influx of new homeless people consists of mentally ill people who would have been admitted to a mental hospital 20 years ago and veteran heroin abusers who are no longer capable of living independently.

Mr. Sleegers is affiliated with the department of youth and mental health of the Municipal Health Service, P.O. Box 2200, 1000 CE Amsterdam, the Netherlands (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Socioeconomic variables relevant to the context of homelessness in the United States and the Netherlands, in percentages

|

Table 2. Prevalence of mental disorders in the United States and the Netherlands, in percentages

1. Jencks CJ: The Homeless. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1994Google Scholar

2. Roofless and Homeless [in Dutch]. The Hague, Health Council of the Netherlands, 1995Google Scholar

3. Burt MR: Over the Edge: The Growth of Homelessness in the 1980s. New York, Russell Sage Foundation, 1992Google Scholar

4. Culhane DP, Dejowski EF, Ibanez J, et al: Public shelter admission rates in Philadelphia and New York City: the implications of turnover for sheltered population counts. Housing Policy Debate 5:107-140, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Toro PA, Warren MG: Homelessness in the United States: policy considerations. Journal of Community Psychology 27:119-136, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Cohen CI: Down and out in New York and London: a cross-national comparison of homelessness. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:769-777, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Report on the Roofless and Homeless [in Dutch]. Amsterdam, Municipality of Amsterdam, 1990Google Scholar

8. Roofless and Homeless: Numbers, Shelter, and Local Policies [in Dutch]. The Hague, Association of Dutch Municipalities, 1990Google Scholar

9. Korf D, Lettink D, Deben L, et al: Roofless and Homeless in Amsterdam 1997 [in Dutch]. Amsterdam, Het Spinhuis, 1997Google Scholar

10. Deben L, Godschalk J, Huijsman C: Roofless and Homeless in Amsterdam and Elsewhere in the Randstad [in Dutch]. Amsterdam, Center for Metropolitan Research, University of Amsterdam, 1992Google Scholar

11. Sleegers J, Spijker J, Van Limbeek J, et al: Mental health problems among homeless adolescents. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 97:253-259, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Link B, Phelan J, Bresnahan M, et al: Lifetime and five-year prevalence of homelessness in the United States: new evidence on an old debate. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 65:347-354, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Fichter MM, Koniarczyk M, Greifenhagen A, et al: Mental illness in a representative sample of homeless men in Munich, Germany. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 246:185-196, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Muñoz M, Vázquez C, Koegel P, et al: Differential patterns of mental disorders among the homeless in Madrid (Spain) and Los Angeles (USA). Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33:514-520, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Rossi PH: Down and Out in America: The Origins of the Homelessness. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1989Google Scholar

16. Employment and Homelessness. Fact sheet no 4. Washington, DC, National Coalition for the Homeless, 1997Google Scholar

17. Statistics Netherlands: Statistical Yearbooks, 1980-1997 [in Dutch]. The Hague, State Printer and Publisher, 1980-1997Google Scholar

18. Statistics Amsterdam: Amsterdam in Numbers, 1982-1997 [in Dutch]. Amsterdam, Statistics Amsterdam, 1986-1997Google Scholar

19. Social and Cultural Report 1990, 1992, 1994, 1996. Rijswijk, the Netherlands, Social and Cultural Planning Office, 1990-1996Google Scholar

20. State and Regional Unemployment, 1997 Annual Averages. Washington, DC, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1998. Available at www.stats.bls.bov/newsrels.htmGoogle Scholar

21. De Beer P: Prolonged periods without work, in The Social Deficit: Fourteen Social Problems in the Netherlands [in Dutch]. Edited by Schuyt K. Amsterdam, De Balie, 1997Google Scholar

22. Rent Guideline Board:1996 Income and Affordability Study. New York, TenantNet, 1996. Available at www.tenant.net/oversight/rgbsum1996/incaff/96incaff.htmlGoogle Scholar

23. Koegel P, Burnam MA, Baumohl J: The causes of homelessness, in Homelessness in America. Edited by Baumohl J. Phoenix, Ariz, Oryx Press, 1996Google Scholar

24. Greenberg MH, Baumohl J: Income maintenance: little help now, less on the way, ibidGoogle Scholar

25. Susser E, Moore R, Link B: Risk factors for homelessness. American Journal of Epidemiology 15:546-556, 1993Google Scholar

26. Hopper K, Jost J, Hay T, et al: Homelessness, severe mental illness, and the institutional circuit. Psychiatric Services 48:659-665, 1997Link, Google Scholar

27. Fisher P, Drake RE, Breakey WR: Mental health problems among homeless persons: a review of epidemiological research from 1980 to 1990, in Treating the Homeless Mentally Ill. Edited by Lamb HR, Bachrach LL, Kass FI. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1992Google Scholar

28. Spijker J, Van Limbeek J, Jonkers F, et al: Psychopathology Among Residents of Long-Term Shelters in Amsterdam [in Dutch]. Amsterdam, Municipal Health Service, 1991Google Scholar

29. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8-19, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Bijl RV, Ravelli A, Van Zessen G: Prevalence of psychiatric disorder in the general population: results of the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33:587-595, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Netherlands Institute of Mental Health: Yearbook Mental Health Care 1996/97 [in Dutch]. Utrecht, De Tijdstroom, 1996Google Scholar

32. Bachrach LL: The state of the state mental hospital in 1996. Psychiatric Services 47:1071-1078, 1996Link, Google Scholar

33. Bachrach LL: Leona Bachrach in the Netherlands: Towards Comprehensive Mental Health. Utrecht, Netherlands Institute of Mental Health, 1990Google Scholar

34. Spijker J, Van Limbeek J, Jonkers JFJ, et al: Trends in First Admissions in Mental Hospitals [in Dutch]. Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie 39:781-789, 1997Google Scholar

35. Statistics Netherlands: Monthly Report on Health Statistics, January 1998 [in Dutch]. Voorburg/Heerlen, Netherlands, Statistics Netherlands, 1998Google Scholar

36. Mechanic D, McAlpine DD, Olfson M: Changing patterns of psychiatric inpatient care in the United States, 1988-1994. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:785-791, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Spruit IP: Yearbook Addition 1996: About Use and Care [in Dutch]. Houten, Netherlands, Bohn Stafleu Van Lochum, 1997Google Scholar

38. Van Brussel G: Services: the Amsterdam model, in Management of Drug Users in the Community. Edited by Robertson R. New York, Oxford University Press, 1998Google Scholar

39. Plomp HN, Van der Hek H, Adèr HJ: The Amsterdam methadone dispensing circuit: genesis and effectiveness of a public health model for local drug policy. Addiction 91:711-721, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar