Best Practices: A Comparative Study of Clinical Events as Triggers for Psychiatric Readmission of Multiple Recidivists

The Southeastern Area of the Department of Mental Health in Massachusetts was the first mental health network to be awarded network accreditation by the Joint Commission for the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO). In late 1994, this network began monitoring specific clinical events as part of a performance improvement project aimed at reducing multiple psychiatric hospitalizations.

Service utilization patterns indicated that 11 clinical events were associated with clients' subsequent clinical decompensation and inpatient readmission. These 11 clinical events were called triggers, and they, along with an intervention system, were known as the Triggers Intervention and Prevention System (TIPS) (1,2). The 11 triggers were four phone calls to the crisis service in seven days, two crisis evaluations in seven days, three crisis evaluations in one month, two missed medication monitoring appointments in a row, an incident report related to the client's mental illness, an incident report involving substance use, admission to an alcohol detoxification facility, two admissions to crisis stabilization beds in one month, three admissions to crisis stabilization beds in six months, a length of stay of more than eight days in a crisis stabilization bed, and an inpatient readmission within six months of discharge.

Under TIPS, each trigger is tracked and screened by a clinician. If the clinician believes that the client shows evidence of decompensation, the client is referred to the clinical review team, who change the treatment plan to prevent a future hospitalization.

TIPS was demonstrated to be an effective early-identification and intervention system when the numbers of admissions and lengths of stay of recidivists and nonrecidivists over a four-year period (1992 through 1995) were compared. Recidivism or "high-end use" was defined as three or more admissions in a 12-month period. Although TIPS had no effect on overall admissions or length of stay, the approach was shown to reduce the number of high-end users in the fourth year, compared with the three previous years when TIPS was not used.

TIPS may also be a promising best practice for reducing the repeated readmissions of multiple recidivists. Consumers having three or more admissions within 18 months constitute the multiple-recidivist population. In longitudinal studies, they have been shown to have significantly more total readmissions and incidents of multiple readmission within a year than consumers having one, or even two, index admissions within 18 months (3). In addition to its general use, TIPS also appears to be well designed for monitoring patterns of service use in this specific population.

In a study in New York State, investigators followed 422 multiple recidivists from five state psychiatric hospitals longitudinally during the 1980s and found that their yearly readmission rates were similar (4). Their readmission pattern over six consecutive years was also found to reliably predict the yearly readmission rates of multiple recidivists from three other hospitals. This pattern of readmission, found in a study involving eight hospitals and 1,456 cases, defined a readmission baseline for multiple recidivists who were receiving traditional clinical services, crisis intervention, and case management.

In current parlance, this readmission pattern is a benchmark of the effectiveness of these traditional services in reducing multiple-recidivist readmissions. The Massachusetts and New York recidivist populations were similar in that they consisted largely of consumers admitted to state mental health facilities who received aftercare, including case management, residential services, medication monitoring, day treatment, psychosocial rehabilitation, and outpatient treatment.

Methods

The multiple-recidivist sample from the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health's Southeastern Area comprised consumers who had three or more inpatient admissions to a network hospital in the Southeastern Area during the 18-month index period, July 1991 through December 1992. The number of yearly readmissions of this sample for each of the next four postindex years, 1993 through 1996, were converted to percentages of the total indexed sample to obtain the sample's pattern of readmission rates. This pattern was then compared with the pattern of readmission rates for the first four years of the study involving the eight New York State hospitals.

During 1993 and 1994, TIPS was not in full effect in Southeastern Massachusetts, but it was fully implemented during 1995 and 1996. Comparisons between the 1993 and 1994 readmission rates and the 1995 and 1996 rates, which would evaluate TIPS' effectiveness, were made using chi square analysis. To determine if TIPS also exceeded the benchmarks for multiple-recidivist readmissions, the 1995 and 1996 rates of readmission were compared with the rates for the third and fourth years reported in the study involving the eight New York state hospitals. This comparison, made using chi square analysis, would determine whether the magnitude of TIPS' effectiveness was superior to that of other interventions.

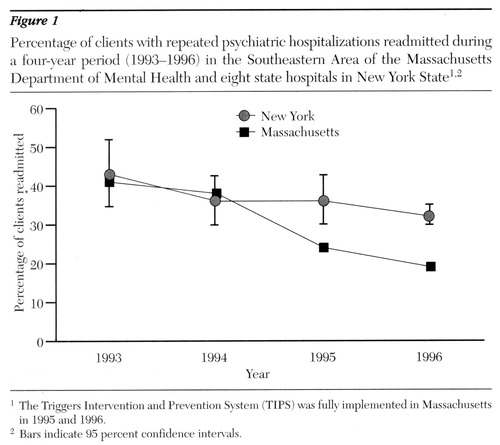

In addition, we hypothesized that the sample's rates for 1993 and 1994 would be within expectations reported for the first two years in the New York State study. Because TIPS was not in full effect during 1993 and 1994, rates for those years were expected to match those in the New York State study if TIPS does define a true baseline for yearly readmissions of multiple recidivists. The New York State readmission rates for the first four postindex years were 43 percent, 36 percent, 36 percent, and 32 percent, respectively.

Results

During the index period, a total of 158 consumers in the Southeastern Area met the operational definition of multiple recidivist. The readmission rates for this sample over the four-year study period (1992 through 1995) were 41 percent, 38 percent, 24 percent, and 19 percent, respectively. The differences between the readmission rates for the first two years and those for the last two years were significant (χ2=23.07, df=1, p<.001). The two years during which TIPS was used had fewer readmissions than the previous two years, when TIPS was not used.

Figure 1 shows the comparison between the rate for the Massachusetts sample and the rates for the New York state hospitals. For the first two postindex years (1993 and 1994), the Massachusetts rates were similar (within 95 percent confidence limits) to the New York State rates. During this time period TIPS was not in full effect. However, during the third and fourth postindex years (1995 and 1996) when TIPS was fully operational, the sample's readmission rates were well below the rates from the New York study (χ2=14.98, df=1, p<.001). During the two years of TIPS operation, the difference in rates was 12 percent and 13 percent, respectively.

To be sure that these observed admission rate reductions from the baseline were associated with TIPS, the use of TIPS during 1995 and 1996 was reviewed. Complete data from all of the network agencies were not available, but data were available from agencies that accounted for 61 percent of the index cohort of multiple recidivists.

These data revealed that 30 percent of the multiple recidivists initiated a trigger clinical event during both 1995 and 1996. Thirty-nine percent of these patients were diverted from inpatient admission during 1995, and 71 percent during 1996. The improved effectiveness of TIPS over time may have been due to the clinical staff's increased familiarity with and full use of the intervention. The proportion of trigger clinical events that resulted in a full clinical case review increased from 19 percent during 1995 to 46 percent during 1996. This dramatic increase in the full utilization of TIPS paralleled a robust increase in admission diversions.

It is also noteworthy that when the number of cases diverted from admission was added to the actual number of admissions for each year, the revised readmission rates were within expectations suggested by the benchmark readmission pattern. The admission diversions that were associated with the TIPS intervention process fully accounted for all of the difference from the benchmark pattern observed in the readmission rates.

Discussion and conclusions

This study demonstrated that TIPS was effective in reducing the readmissions of multiple recidivists for two consecutive years and that the reduction exceeded baseline expectations for this population of consumers. Studies have shown that multiple recidivists have consistently accounted for 19 to 30 percent of public psychiatric hospital admissions (3,5,6,7). TIPS' sustained effectiveness with this subpopulation is particularly noteworthy because of the repeated use of high-cost services by these clients. Admission and census reductions achieved by TIPS could conceivably affect a mental health network's resource allocation and service delivery in addition to a particular hospital's operating costs and profits.

This study also replicated in Massachusetts and in a more recent time period part of the pattern of multiple recidivists' readmissions observed in New York during the 1980s. The pattern may well describe a useful baseline for this population where the care system includes such services as medication, day treatment, crisis teams, and case management. TIPS surpassed this benchmark and can claim best-practice status in reducing the readmissions of multiple recidivists. Future intervention strategies would have to exceed the benchmarks set by TIPS in this study.

The two-pronged approach of TIPS may well account for its efficacy. First, TIPS identifies specific events that have been observed to be related to psychiatric hospital admission. These events are the triggers that are continuously monitored throughout the network by risk managers. They may be routine and unremarkable for most patients. However, for high-risk patients, they signal an impending relapse and represent opportunities to intervene decisively.

Once observed, these triggers initiate TIPS' second prong—a consistent, planned response throughout the service network. The continuous monitoring coupled with a swift, standard, and decisive response by clinical staff are the key ingredients of TIPS.

Continuous improvement of TIPS would focus on both prongs of the approach. Reviewing future admissions to discover additional triggers would be one effort. Reviewing the interventions that were recommended by case review initiated by a trigger would serve to identify and isolate new or most effective interventions for future use with these high-risk clients.

Psychiatric Services Resource Center Releases Compendium on Families

A compendium of 13 articles on families and their involvement in mental health treatment has just been released by the Psychiatric Services and Hospital and Community Psychiatry.

Lisa B. Dixon, M.D., a Baltimore psychiatrist who is active in the family advocacy movement, wrote the introduction to the 72-page compendium, entitled Family & Mental Health Treatment. The articles focus on the needs and concerns of families of adults with severe and persistent mental illness, highlight the family and parenting needs of persons suffering from mental disorders and their children, and examine the costs to families associated with severe mental illness.

A copy of the compendium will be sent free to mental health facilities enrolled in the Psychiatric Services Resource Center. Staff in Resource Center Facilities may order additional single copies (regularly priced at $13.95) for $8.95. For ordering information, call the Resource Center at 800-366-8455 or fax a request to 202-682-6189.

Dr. Frazier is director of risk management at the John C. Corrigan Mental Health Center, 49 Hillside Street, Fall River, Massachusetts 02720 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Casper is clinical director at Keystone House in Norwalk, Connecticut. William M. Glazer, M.D., is editor of this column.

Figure 1. percentage of clients with repeated psychiatric hospitalization readmitted during a four-year period (1993-1996) in the Southeastern Area of the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health and eight state hospitals in New York State1,2

1 The Triggers Intervention and Prevention System (TIPS) was fully implemented in Massachusetts in 1995 and 1996

2 Bars indicate 95 percent confidence intervals.

1. Frazier RS, Amigone DK: Using signs of decompensation as triggers for early intervention to reduce hospitalization. Psychiatric Services 48:621-623, 1997Link, Google Scholar

2. Frazier RS, Amigone DK, Sullivan JP: Using continuous quality improvement strategies to reduce repeated admissions for inpatient psychiatric treatment. Journal of Healthcare Quality 19:6-10, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Casper ES, Pastva G: Admission histories, patterns, and subgroups of the heavy users of a state psychiatric hospital. Psychiatric Quarterly 61:121-134, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Casper ES, Romo JM, Fasnacht RC: Readmission patterns of frequent users of inpatient psychiatric services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:1166-1167, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Weinstein AS: The mythical readmission explosion. American Journal of Psychiatry 140:331-335, 1983Google Scholar

6. Vioneskos G, Denault S: Recurrent psychiatric hospitalization. Canadian Medical Association Journal 118:247-250, 1978Medline, Google Scholar

7. Carpenter MD, Mulligan JC, Bosler IA, et al: Multiple admissions to an urban psychiatric center. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 36:1305-1308, 1985Abstract, Google Scholar