Rehab Rounds : Replicating Effective Supported Employment Models for Adults With Psychiatric Disabilities

Abstract

Introduction by the column editors:Many barriers must be overcome for the successful dissemination and adoption of model programs in mental health (1). Generally, the more complex and demanding of resources the model program is, the more obstacles are encountered in its effective "transplantation." Some facilities or agencies simply lack the fertile fields required by resource-rich model programs. For example, the Program for Assertive Community Treatment (PACT) requires a staff-to-patient ratio of one to 20 or less. Few mental health agencies can afford that level of staffing.Another obstacle to successful dissemination is the resistance of staff at the receiving site to adopt a new model that might be philosophically incongruent with their previous approach to clients. One example is Maudsley Hospital's attempt to implement the home-based, PACT model of service delivery in a poor section of London (2). Even at this resource-rich, academic hospital—the premier psychiatric hospital for training and research in the United Kingdom—the model ultimately failed because the Maudsley Hospital staff clamped down on the autonomy of the community-based team after a PACT consumer murdered a baby and the tragedy received national media attention. The hospital and community-based team returned to the more traditional, hospital-based service philosophy with audits and utilization review tightly controlled by the hospital.Similarly, the introduction of the PACT model has failed in some state systems in the United States where staff have been reluctant to shift their professional roles toward mobile, outreach, and in vivo activities, even when the state's top management endorsed the model program.In this month's Rehab Rounds column, Neil Meisler and Olivia Williams describe the trials and tribulations of mounting two model programs—PACT and Individual Placement and Support (IPS) —for seriously mentally ill consumers in a rural mental health center in South Carolina. The authors describe how the individuals responsible for adopting these model programs had to make many compromises, leading to a common feature of successful adoption of innovations— "reinvention" of the model program to fit the unique constraints, resources, limitations, and staffing available in the host setting (3).

The rural-based supported employment approaches project at the Santee-Wateree Community Mental Health Center in Sumter County, South Carolina, is one of eight sites of the employment interventions demonstration project sponsored by the Center for Mental Health Services. When the project began in 1996, we planned to implement and compare two model rehabilitative programs with established efficacy in research trials for adults with severe and persistent mental illness.

One program, Individual Placement and Support (IPS), developed in 1989 by Drake and colleagues (4) at the New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center, has demonstrated a 40 percent rate of competitive employment over an 18-month follow-up period. The other approach, the Program of Assertive Community Treatment with integrated vocational rehabilitation (PACT-IVR), has achieved competitive employment rates as high as 50 percent (5). In comparison, employment rates between 5 and 25 percent have been reported for conventional community support programs (6,7).

Subjects were to have been randomly assigned to one of three conditions. The first was the PACT-IVR program, in which the assigned subjects would have received all of their treatment, rehabilitation, and support services through a PACT model of service delivery. The second condition was the IPS program, in which an employment specialist would have engaged subjects in employment-related services while planning and coordinating overall service provision with the other units of the community mental health center that were also serving IPS clients.

The third condition was the Genesis Center, an existing free-standing vocational center in which consumers participate in a sheltered workshop designed to serve as a work adjustment experience while they are pursuing community employment with assistance from Genesis Center job coaches. Subjects assigned to the Genesis Center condition would have received outreach and care coordination by case managers affiliated with the community mental health center who were specifically assigned to the project and who worked with consumers in a one-to-35 ratio.

Implementation problems

From the outset of our project, we experienced difficulty in recruiting personnel who had the training and experience called for by the PACT-IVR and IPS models. We were unable to find program coordinators with relevant experience for either model. We hired a master's-level social worker with program management experience for the PACT coordinator position, but this person lacked clinical training and experience pertaining to persons with severe and persistent mental illness. For the IPS unit, we hired a master's-level rehabilitation specialist whose training and experience was in working with youth in school-based programs.

Although we were able to immediately recruit a psychiatrist for the PACT program, our difficulty filling the positions for the registered nurse and master's-level counselors frustrated our efforts to implement the PACT-IVR model. Also, shortly after the project began, the IPS coordinator resigned to accept a position with a school department. Even after three rounds of advertising, we were unable to identify a qualified replacement for the coordinator. After four months of operation, we began to consider program modifications to compensate for the slow pace of staff recruitment and lack of clinical experience among the available staff.

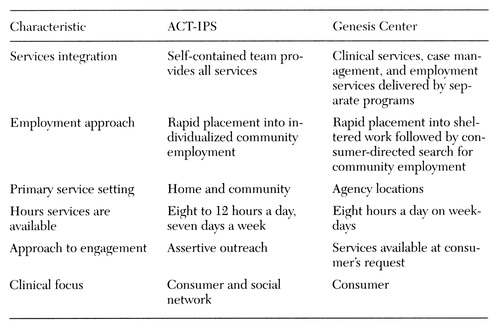

In consultation with the founders of both models, who were engaged to conduct staff training and monitor our implementation, we decided to merge the PACT-IVR and IPS conditions into a single program, which we called ACT-IPS (Assertive Community Treatment-Individual Placement and Support). The study design remained a randomized, controlled trial, comparing the ACT-IPS hybrid model to the existing vocational rehabilitation program at Genesis Center. The program differences between the ACT-IPS and the Genesis Center are highlighted in Table 1.

Subjects in the study had the following profile: 62 percent were female, 74 percent were African American, and 51 percent had completed high school. Their mean age was 37 years. Forty-two percent had schizophrenic disorders, 41 percent had major affective disorders, and 17 percent had other disorders, including substance use and personality disorders.

Replication training and monitoring

We are continuing to attempt as close a replication of the elements of the PACT model as possible (8). We are implementing IPS as the vocational intervention within the ACT program, adhering to the specifications of the IPS model. The IPS employment specialists and other ACT staff work out of the same location and are comembers of the team. Each consumer has a primary treatment team consisting of a psychiatrist, a registered nurse, a primary clinician (if other than the registered nurse), and a vocational specialist. Vocational specialists do not serve as primary clinicians for consumers, and they provide only vocational services.

Project consultants conduct bimonthly site visits to the ACT-IPS team to provide in-service training and monitor the fidelity of the ACT-IPS team to PACT and IPS standards. After each visit, the consultant for each model submits a fidelity rating and written report indicating the team's progress. In addition, a PACT model consultant from Madison, Wisconsin, conducts telephone conferences with the team, participating biweekly in a daily team meeting and monthly in a treatment planning meeting. An IPS consultant from New Hampshire participates by telephone in the weekly IPS supervision meeting.

As the project ends its second year of operation, the ACT-IPS team has made substantial progress, but neither model has been fully implemented. The most recent report of the lead IPS consultant indicated that IPS is nearing fidelity to the model. Consultation and training are currently focused on engaging consumers who are avoiding contact and on increasing the work motivation among consumers who have been in the program for several months but have not yet held a job. Another area of focus is increasing the individualization of job development.

The most recent monitoring report for PACT indicated substantial progress toward adherence to most program elements. The main focus of training and consultation is currently on formulating comprehensive treatment plans, converting treatment plans into weekly schedules that drive the team's interaction with consumers, increasing the intensity of service provision, and increasing collaboration with consumers' support networks.

Discussion

ACT-IPS had 59 consumers actively enrolled and six dropouts after two years of implementation. Sixty percent of the ACT-IPS consumers have held at least one job since entering the program. The employment rate has fluctuated between 25 and 40 percent over the two-year period. Whether the proportion of consumers entering employment and retaining employment will increase over the next two-year data collection period will depend largely on the success of the ACT-IPS team in achieving the depth of clinical engagement, assessment, treatment planning, and service provision associated with the Madison, Wisconsin, and New Hampshire public mental health service systems, where these two models were developed. Our goal is to demonstrate that with a high level of commitment and extended training and monitoring, settings like rural Sumter County, where staff with advanced degrees and prior experience in assertive community treatment are not available, can attain results similar to those attained by the model innovators.

The creators of PACT and IPS demonstrated that many consumers with serious mental illness can attain employment. However, replication of these models is difficult. Agency commitment to consumer employment, adherence to the core components of the program model, and intensive training and monitoring by experts in the model appear to be the key ingredients for a successful replication effort.

Afterword by the column editors:

The adoption of innovations, such as PACT and IPS, may be eased by simplifying these programs and making them more user friendly. Mr. Meisler and his colleagues encountered great problems in recruiting, training, and retaining staff who could master the PACT-IVR and IPS programs. These programs are marked by their considerable demands on the professional skills and personal qualities of their staff. It would be interesting to see if widespread and high-fidelity dissemination of these programs would be facilitated by breaking them into components, or modules, each with its own step-by-step and prescriptive practitioner's manual. Use of these formats has facilitated dissemination of the modules in the UCLA Social and Independent Living Skills Program, which have been adopted by agencies in 48 of the 50 states and translated into 15 different languages, including Chinese and Arabic (9).

Other technology transfer principles that could facilitate the adoption of even complex programs include the use of direct demonstrations of the program with clients from the host site by expert consultants who originally designed the program; cultivating local champions or influential individuals at the host site who are respected by their colleagues for their clinical astuteness and professional judgment; and using incentives for staff who take on the new roles in implementing the model programs. These principles were utilized with great effectiveness and durability at the South Carolina State Hospital by Rosalind Smith and her colleagues as was described in a previous Rehab Rounds column (10).

The most important determinant of adoption of a human service innovation, however, is the persistent, persuasive, and visible mandate for the innovation by leadership of the host organization—from top and middle managers and administrative and clinical leaders. Mr. Meisler and his team in rural South Carolina did in fact gain the support of their agency's leadership, with substantial impact, even if the original research design had to be sacrificed on the altar of expediency. Many leaders and managers are content to push motivational techniques that do little more than manipulate their staff, but they avoid creating a new vision for making fundamental changes in their agencies. Such inspiration, and the changes it encourages, can galvanize burned-out practitioners into teams that find meaning and self-actualization by reaching for their leaders' vision and their clients' improvement (11).

Mr. Meisler is administrative director for public psychiatry at the Medical University of South Carolina, 261 Cannon Park Place, Room 209, Charleston, South Carolina 29425 (e-mail, [email protected]). Ms. Williams is executive director of the Santee-Wateree Community Mental Health Center in Sumter, South Carolina. Robert Paul Liberman, M.D., and Alex Kopelowicz, M.D., are editors of this column.

|

Table 1. Program characteristics of assertive Community Treatment-Individual Placement and support(ACT-IPS) and the Genesis Center

1. Backer TE, Liberman RP, Kuehnel TG: Dissemination and adoption of innovative psychosocial interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 54:111-118, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Marks IM, Connolly J, Muijen M, et al: Home-based versus hospital-based care for people with serious mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry 165:179-194, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Hannah GT, Fishman DB: A view from the top: applying behavioral principles in the role of state commissioner of mental health and retardation services: case study 3. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management 6:35-44, 1984Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Becker DR, et al: The New Hampshire study of supported employment for people with severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64:391-399, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Knoedler W: Comments on "individual placement and support." Community Mental Health Journal 30:207-209, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Anthony WA, Blanch A: Supported employment for persons who are psychiatrically disabled: a historical and conceptual perspective. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 11(2):5-23, 1987Google Scholar

7. Bond GR, McDonel EC: Vocational rehabilitation outcomes for persons with psychiatric disabilities, an update. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 1:9-20, 1991Google Scholar

8. Allness DJ, Knoedler W: The PACT Model of Community-Based Treatment for Persons With Severe and Persistent Mental Illness: A Manual for PACT Start-Up. Arlington, Va, National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, 1998Google Scholar

9. Liberman RP, Wallace CJ, Blackwell G, et al: Innovations in skills training for the seriously mentally ill: the UCLA Social and Independent Living Skills modules. Innovations and Research 2:43-60, 1993Google Scholar

10. Smith RC: Implementing psychosocial rehabilitation with long-term patients in a public psychiatric hospital. Psychiatric Services 49:593-595, 1998Link, Google Scholar

11. Maslow A: Maslow on Management. New York, Wiley, 1998Google Scholar