The Impact of Mental Illness Status on the Length of Jail Detention and the Legal Mechanism of Jail Release

Many people with mental illness are in jails and prisons ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ). According to recent rigorous estimates, 14.5% of men and 31.0% of women recently incarcerated in jails have a serious mental illness ( 8 ). Some service providers and researchers have speculated that people with mental illnesses are less likely than those without a mental illness to be released by early-release mechanisms ( 9 ). Although this premise is generally true for prisons ( 10 ), it remains untested in jails. On the basis of the assumption that people with mental illness have longer jail detentions, many postbooking diversion programs are justified in their aim of reducing the length of time in jail ( 11 ). Research has yet to rigorously examine how long people with mental illnesses are detained or the mechanisms by which they are released.

Understanding the extent to which the timing and manner of jail releases are influenced by mental illness status has important implications for mental health services planning. Unlike prisons, jails are community-based facilities that have frequent interactions with the communities they serve. The difference is evident when the population dynamics of prisons and jails are compared. Nationally, the number of people incarcerated in prisons is just over two million, and an estimated 650,000 prison releases occur each year ( 12 ). In contrast, jails represent a relatively small proportion of the total number of incarceration beds—about 700,000 of more than 2.3 million beds—but a much larger number of detentions, as represented by approximately nine million jail releases each year ( 13 , 14 , 15 ). These numbers challenge the capacity of the mental health system to provide access to treatment for the 14% to 31% of the nine million released jail inmates who have a mental illness ( 2 , 16 , 17 ), nearly two-thirds of whom may not have received treatment while detained ( 18 ).

Planning release from jail and prison differs in the unpredictability of the release date ( 19 ). Jails house both sentenced and unsentenced populations, and thus the number of legal mechanisms by which people are released is larger in jails than in prisons. Some jail release mechanisms are associated with shorter detentions and with release dates that are more unpredictable, and even spontaneous, such as release on bail or from court. Other release mechanisms are associated with longer sentences and more predictable release dates, such as completion of a sentence or parole. To maximize service capacity, programs for people with mental illnesses who are leaving jail need to incorporate an understanding of how long people with mental illness typically stay in jail and how they are being released from these facilities.

The study reported here contributes to this understanding by examining the following questions: Among people who go to jail, do those with serious mental illnesses stay in jail longer than other detainees? To what extent do mechanisms of jail release differ by mental illness status?

Methods

Data from two sources were used to model the interaction of mental illness status and length of jail detentions in a major urban center of the United States. The data were drawn from two administrative data sets: Medicaid records from the City of Philadelphia behavioral health system and data provided by Philadelphia County's jail system, which included data on admission, release dates, and type of discharge as well as basic demographic information, such as birth date, sex, and race-ethnicity. Medicaid data were drawn for all adults between the ages of 18 and 64 who were living in the City of Philadelphia and eligible for Medicaid in Pennsylvania in 2003. These Medicaid records were matched with the jail records for all admissions in 2003. Cases were matched by using an algorithm with a combination of factors that include first and last name, date of birth, sex, and Social Security number ( 20 ). Because the Medicaid data used in this analysis were for the time before jail detention for each case, the suspension or termination of Medicaid eligibility during incarceration would not have an impact on this analysis.

These matched records created a file that contained Medicaid and jail data for all admissions to the jail in 2003 (N=24,290). Release data were available for all 2003 jail admissions that occurred through August 2005 (N=20,573). Medicaid claims data for 2001 through 2003 were used to identify individuals with a serious mental illness—that is, those with a diagnosis either in the schizophrenia spectrum ( DSM-IV code 295.XX) or of a major affective disorder ( DSM-IV code 296.XX). Diagnoses were restricted to the more serious mental illnesses because services in the public mental health system are typically targeted toward individuals with these diagnoses. Persons were considered to have one of the two disorders when the relevant diagnosis was present in one inpatient or two outpatient Medicaid claims records within the specified time period.

Descriptive statistics were used to compare the sociodemographic characteristics and release mechanisms for persons with and without serious mental illnesses. Measures of central tendency were used to examine the length of stay by mental illness status. The Kaplan-Meier method ( 21 , 22 ) was used to estimate survival curves, stratified by mental illness status, for durations of all jail episodes in 2003 (N=24,290). Generalized estimation equations were used when appropriate to account for the violations to independence created by the potential for a person to be incarcerated more than one time in 2003. All data management, matching, and analyses were performed using SAS statistical software. Institutional review boards for the University of Pennsylvania and the City of Philadelphia Department of Public Health approved and oversaw this research.

Results

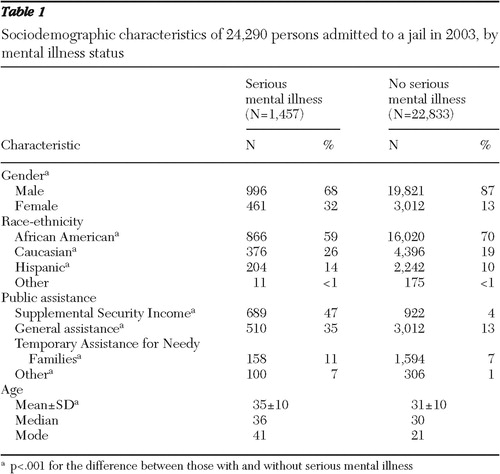

Table 1 presents data on the sociodemographic characteristics of persons admitted to jail in 2003. Overall, 6% of the sample (1,457 of 24,290) had Medicaid claims that indicated a diagnosis of a serious mental illness. This rate is consistent with some of the more rigorous estimates of the prevalence of serious mental illness in jails ( 17 , 23 ). Compared with those without serious mental illnesses, the group with these disorders had a greater diversity in both gender and ethnicity, and they were significantly older. This may hint at some differences in pathways to jail between the two groups. Persons with serious mental illnesses were far more likely to be receiving Supplemental Security Income, which is not surprising given the presence of psychiatric disability in this group. In the overall sample, 11% (N=2,672) had a diagnosis of either drug or alcohol dependence ( DSM-IV codes 303.XX and 304.XX) and 4% (N=972) had a dual diagnosis of both a serious mental illness and a substance dependence disorder.

|

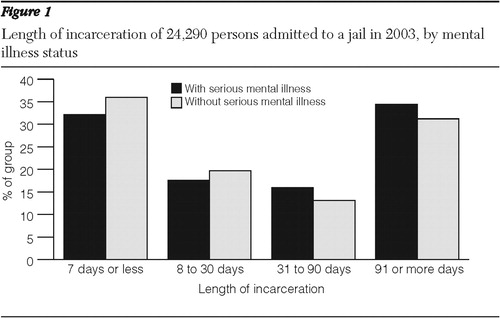

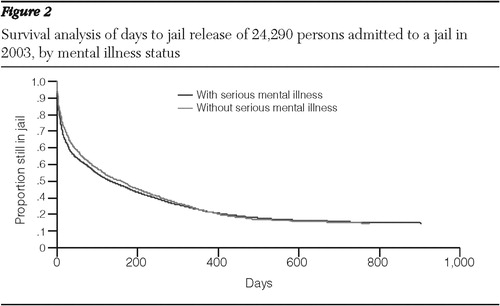

The mean±SD number of days in jail for all stays completed by September 1, 2005 (N=20,573), was 112±149, with a median of 36 days and a mode of two days. Figure 1 shows the length of detention by mental illness status. Even though there are some differences between the groups, such as a lower proportion of releases in the first seven days of detention among persons with serious mental illnesses, the pattern of release by time period is strikingly similar for the groups. The similarity is supported by data shown in Figure 2 , which displays the survival curves for time to jail exit for persons with and without serious mental illnesses who were admitted to jail in 2003 (N=24,290). The survival curves are not significantly different. Fifty percent of the group with serious mental illnesses were released within the first 30 days of incarceration, compared with 56% of the other detainees.

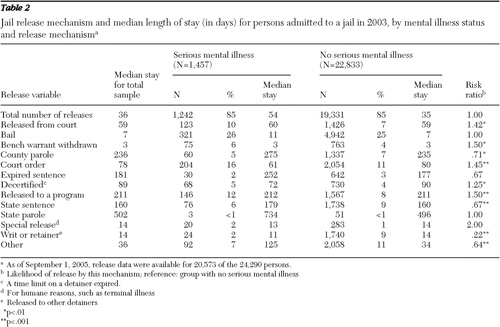

Table 2 presents data on mechanisms of release and median length of stay by mental illness status (N=24,290). Comparisons by mental illness status are shown for each release mechanism. Because of the large data set, only relationships that were significant at a level of <.01 and that had a difference in risk ratios of 10% or more (.9 or lower or 1.1 or higher) were considered. Persons with serious mental illnesses who were released during the study period were released more often by discharge mechanisms that are associated with unpredictable, sometimes quick, releases by court authorities (bail, release from court, withdrawal of bench warrant, decertification, and special release). A total of 607 (49%) of persons with serious mental illnesses were released by these mechanisms, compared with 8,144 (42%) of the other detainees released. In the release categories that are associated with longer stays or more predictable releases, the tendency was in the opposite direction—those with serious mental illnesses were less likely to be released through these mechanisms. A total of 236 (19%) persons with serious mental illnesses were released by these mechanisms, compared with 3,546 (18%) of the other detainees. Examples of more predictable releases are release on county parole (Pennsylvania is an anomaly among states because it has a system of both county- and state-level parole), release after serving an entire sentence, and release to a program.

|

Discussion and conclusions

Overall, the lengths of jail stays were found to be strikingly similar among persons with a diagnosis of a serious mental illness and those without such a diagnosis. Regardless of mental illness status, at least 50% of persons were released from jail within 30 days of entering. Furthermore, nearly half (49%) of those with serious mental illnesses had relatively unpredictable releases. Many such releases occurred after shorter incarcerations, typically with little or no notice, and an additional 8% left the jail for state sentences or incarceration in a state or other county facility.

This means that among persons admitted in 2003, only 19% (those released through parole or an expired sentence or released to a program) served sentences that allowed reasonably sufficient time for programming on the basis of a planned, anticipated release date. Providers who develop programs based on the assumption that those with mental illnesses have longer jail stays will miss a significant number of jail detainees in need of specialized mental health services. Mental health programs designed to deliver services to persons admitted to jails must have the capacity to respond to the full range of legal mechanisms of release—that is, to provide services for persons with short or longer-term detentions.

Strengths and limitations of administrative data

This study analyzed administrative data, which represented the only practical means of identifying persons with diagnosed serious mental illnesses among those incarcerated in the county jail system. However, the analysis has limitations. Although Medicaid claims data for three years before jail admission were used to maximize the number of persons identified as having a serious mental illness diagnosis, some persons with serious mental illness were missed by the matching process, either because of data shortcomings or because no diagnosis was recorded in the claims data. The extent of unidentified serious mental illness among this jail population is unknown. Furthermore, these data are from public mental health and jail systems in a single city, which has been relatively resourceful in creating multiple means of service linkage, and other systems may have differing results.

Jail detainees can be divided into those who have a sentence and those who do not. This distinction is difficult to make with these data. The best indicator is the mechanism of release, because some mechanisms are closely linked to sentencing status. However, sentencing status is not as clear for some mechanisms. Because we could not confidently distinguish between sentenced and unsentenced groups in this data set, we could not analyze by sentencing status. Mental illness status and sentencing status may interact to extend the length of jail detentions. Although we could not test this directly, our data on release mechanisms indicate that sentencing status did not play a significant role in length of detention.

Implications and future research directions

Such limitations notwithstanding, this is the first analysis to our knowledge to examine in detail relationships between mental illness and length of jail detention and mechanisms of release. The findings raise important questions that should be addressed in future research and planning initiatives.

Most people leave jail in less than a month. Programs that identify people with mental illness in jail and provide them with access to treatment and reentry services need to incorporate engagement strategies for those who have quick, often unpredictable, releases, which are commonplace among all jail detainees. Jail is a difficult experience, and most people in jail understandably want to be released. In many cases, they are released within days. Even among those with stays of three or four weeks, the typical jail detainee is holding on every day to the thread of hope that he or she will be released that day or the next. To engage all jail detainees in need of mental health services, service planners need to be flexible and develop strategies for immediate engagement and promise of support after release, on the chance that the provider is meeting the client on the day of release.

The mechanisms of release that are associated with mental illness status include some that may be linked to postrelease service planning, such as release by court order or release to a program. Such a release may result from the efforts of a public defender, a social worker, or a previously assigned case manager who has developed a postrelease plan for housing and treatment. Further research should examine how these release mechanisms are linked to supportive services that expedite release on the basis of access to services and treatment.

Future research should focus on the development of new intervention models for people with mental illnesses in jails. For instance, many models of jail diversion rely on casework models, which require efforts at case finding, eligibility determination, clinical engagement, and service planning. This individualized process is not feasible for a large mass of people who move through an institution with stays of one month or less. Interventions need to be developed to engage people who need mental health services by using technologies other than casework for those who are in jail for shorter periods of time. For example, jail "in-reach" or group-based education or empowerment interventions ( 24 ) may provide models for less time-consuming, more immediately engaging interventions that connect individuals to service providers and other new social ties ( 25 ).

Future research could also use primary data collection methods to make up for limitations in administrative data. For example, cohort studies of persons leaving jail can be designed by creating a sample of individuals entering jail and conducting follow-ups at release and in the community. Clinical diagnoses can be confirmed by use of standardized instruments. Given the public health importance of intervention development for this population, such studies could be carried out in multiple jurisdictions to enhance generalizability beyond a single, unique system.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This is one of several studies of the dynamics of mental illness in an urban jail system sponsored in part by the City of Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health Services and by the Philadelphia Prison System. The authors thank Steven C. Marcus, Ph.D., for help with data analysis and presentation.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Teplin LA: The criminalization of the mentally ill: speculation in search of data. Psychological Bulletin 94:54–67, 1983Google Scholar

2. Ditton PM: Mental health and Treatment of Inmates and Probationers. Washington, DC, Bureau and Justice Statistics, 1999Google Scholar

3. Abramson MF: The criminalization of mentally disordered behavior: possible side-effect of a new mental health law. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 23:101–105, 1972Google Scholar

4. Teplin LA: Criminalizing mental disorder: the comparative arrest rate of the mentally ill. American Psychologist 39:794–803, 1984Google Scholar

5. Torrey EF: Jails and prisons: America's new mental hospitals. American Journal of Public Health 85:1611–1613, 1995Google Scholar

6. Kupers TA: Prison Madness: The Mental Health Crisis Behind Bars and What We Must Do About It. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1999Google Scholar

7. Isaac RJ, Armat VC: Madness in the Streets: How Psychiatry and Law Abandoned the Mentally Ill. New York, Free Press, 1990Google Scholar

8. Steadman HJ, Osher FC, Robbins PC, et al: Prevalence of serious mental illness among jail inmates. Psychiatric Services 60:761–765, 2009Google Scholar

9. Hoff RA, Rosenheck RA, Baranosky MV, et al: Diversion from jail of detainees with substance abuse: the interaction with dual diagnosis. American Journal of Addiction 8:201–210, 1999Google Scholar

10. Metraux S: Examining relationships between receiving mental health services in the Pennsylvania prison system and time served. Psychiatric Services 59:800–802, 2008Google Scholar

11. Steadman HJ, Deane MW, Morrissey JP, et al: A SAMHSA research initiative assessing the effectiveness of jail diversion programs for mentally ill persons. Psychiatric Services 50:1620–1623, 1999Google Scholar

12. Petersilia J: When Prisoners Come Home: Parole and Prisoner Reentry. New York, Oxford University Press, 2003Google Scholar

13. Freudenberg N, Daniels J, Crum M, et al: Coming home from jail: the social and health consequences of community reentry for women, male adolescents, and their families and communities. American Journal of Public Health 95:1725–1736, 2005Google Scholar

14. Penn DL, Mueser KT, Spaulding W: Information processing, social skill, and gender in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research 59:213–220, 1996Google Scholar

15. Sabol WJ, Minton TD, Harrison PM: Prison and jail inmates at midyear 2006. Bureau of Justice Statistics, US Department of Justice, 2007Google Scholar

16. Abram KM, Teplin LA, McClelland GM: Comorbidity of severe psychiatric disorders and substance use disorders among women in jail. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:1007–1010, 2003Google Scholar

17. Teplin LA: Psychiatric and substance abuse disorders among male urban jail detainees. American Journal of Public Health 84:290–293, 1994Google Scholar

18. Teplin LA: Detecting disorder: the treatment of mental illness among jail detainees. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 58:233–236, 1990Google Scholar

19. Draine J, Herman DB: Critical time intervention for reentry from prison for persons with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 58:1577–1581, 2007Google Scholar

20. Campbell KM, Deck D, Krupski A: Record linkage software in the public domain: a comparison of Link Plus, the Link King, and a basic deterministic algorithm. Health Informatics Journal 14:5–15, 2008Google Scholar

21. Asnis GM, Kaplan ML, Hundorfean G, et al: Violence and homicidal behaviors in psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 20:405–425, 1997Google Scholar

22. Allison P: Survival Analysis Using the SAS system: A Practical Guide. Cary, NC, SAS Publishing, 1995Google Scholar

23. Freudenberg N: Jails, prisons, and the health of urban populations: a review of the impact of the correctional system on community health. Journal of Urban Health 78:214–235, 2001Google Scholar

24. Ghose T, Swendeman D, George S, et al: Mobilizing collective identity to reduce HIV risk among sex workers in Sonagachi, India: the boundaries, consciousness, negotiation framework. Social Science and Medicine 67:311–320, 2008Google Scholar

25. Hawe P, Shiell A: Social capital and health promotion: a review. Social Science and Medicine 51:871–885, 2000Google Scholar