Clinician Perceptions of Virtual Reality to Assess and Treat Returning Veterans

High rates of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and related problems have been noted among military personnel returning from Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) ( 1 , 2 ). Thus innovative, effective interventions are needed for symptom assessment, monitoring, and treatment. Virtual reality offers a unique assessment method for OEF-OIF veterans by allowing for controlled immersion in a simulated combat environment while monitoring psychophysiological reactivity ( 3 ). The technology has also been used as an adjunct to exposure therapy and has improved PTSD symptoms among veterans ( 3 , 4 , 5 ). Case studies have also demonstrated the feasibility of using virtual reality clinically and a general acceptance of virtual reality by patients ( 4 , 6 ).

Despite these results, no studies have explored clinicians' perceptions of virtual reality technology. The closest data available, reported by Cahill and colleagues ( 7 ), attributed poor dissemination of exposure therapy (without virtual reality) to lack of training and concerns about tolerability and safety. Because mental health clinicians are likely to refer to, use clinical data obtained from, and conduct screening or treatment with virtual reality, we conducted focus groups with them to determine critical factors in the successful implementation of this intervention among veterans.

Methods

A convenience sample of nine male and nine female clinicians was recruited from a Veterans Health Administration (VHA) hospital (PTSD clinic, substance abuse treatment service residential program, and mental health clinic) in the mid-South. Because of potential differences in referrals to or usage of virtual reality, participants were differentiated by whether they had prescribing privileges (seven psychiatrists, three advanced practice nurses, and one clinical pharmacist) or not (three social workers and four psychologists). Sixteen clinicians (89%) were Caucasian, one (6%) was African American, and one (6%) was Asian American. None of the clinicians had experience using virtual reality clinically, but two (11%) had attended virtual reality training.

Four on-site focus groups, approximately one hour in duration, were facilitated in 2008 by an expert in focus group methods who was not associated with any past or current virtual reality studies. Two focus groups explored virtual reality as an assessment tool, and two focus groups explored virtual reality as a treatment adjunct. The study was approved by a VHA Institutional Review Board and Research and Development Committee. Written informed consent was obtained.

At the outset of the focus groups, a brief explanation of virtual reality, including photos and videos, was provided. Participants were initially asked, "What are your thoughts about using virtual reality as a potential assessment (or treatment) tool for veterans with PTSD?" Subsequent probe questions were asked.

Group comments were digitally recorded, transcribed, checked for accuracy, and downloaded into Ethnograph software. The research team collaboratively developed categories and definitions for first-level coding. Two investigators (TLK and PES) independently coded the transcripts; their coding had a concordance rate of 80%. Secondary- and tertiary-level coding was also completed. [Further description of the analysis is available as an online appendix to this brief report at ps.psychiatryonline.org .]

Results

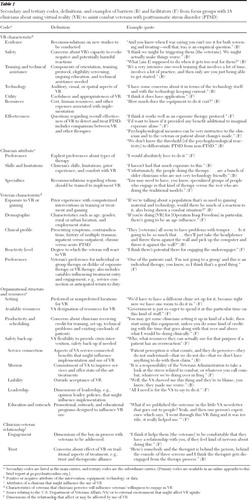

Primary coding consisted of barriers and facilitators to implementation of virtual reality. Barriers were factors that would prevent or impede utilization, implementation, or uptake. Facilitators were factors that would enhance or increase utilization, implementation, or uptake. See Table 1 for definitions and examples of secondary and tertiary codes. Frequencies of codes in transcripts were also recorded for quantitative analysis. [A table showing the perceived barriers and facilitators to virtual reality is available in the online appendix to this brief report at ps.psychiatryonline.org .]

|

The most robust facilitator appeared to be the timely, culturally driven popularity of computer technology. Virtual reality was perceived as a step forward in treatment, and several clinicians emphasized it would be very acceptable to OEF-OIF veterans, many of whom are young, computer savvy, and familiar with electronic gaming devices and programs. Beyond this finding, differences in virtual reality as an assessment versus treatment tool were noted.

Of the five secondary codes, clinicians were most likely to discuss the qualities that were either problematic or helpful in using virtual reality as an assessment tool. Although several understood how virtual reality might be used to assess symptoms, others raised specific questions about its accuracy in detecting PTSD or its symptoms. Although clinicians were impressed with the technological capabilities of virtual reality, they were also concerned that some of the scenes were "cartoonish," which they thought might influence the reliability and validity of symptom assessment. Clinicians also raised safety concerns, such as whether exposure to the virtual reality environment would exacerbate a veteran's symptoms.

Veteran and clinician characteristics important to virtual reality as an assessment tool were also discussed frequently. Clinicians were concerned that veterans seeking or having already obtained service-connected disability benefits for mental health problems might resist this type of assessment out of fear that the results might negatively influence their status. Clinical issues that might influence a veteran's willingness or ability to participate in a virtual reality assessment included comorbid medical conditions, complex trauma, and medication. Clinicians also wanted a select group of providers—such as virtual reality technicians—to be trained to have the expertise to use the equipment and software, support veterans with atypical or distressed responses, and consult with other professionals on the assessment output.

The most prevalent barriers and facilitators for treatment implementation concerned virtual reality's characteristics. Clinicians were impressed by the capabilities of the technology but expressed concern that the scenes may not be realistic or specific enough to trigger and eventually reduce combat-related anxiety. Clinicians acknowledged the evidence base for exposure therapy for combat-related PTSD but questioned whether virtual reality enhanced its effectiveness. With regard to veteran and clinician characteristics, all clinicians said their lack of skill and experience with the technology was a barrier to implementation, but nonprescribers—the group most likely to provide exposure therapy—were more likely to suggest training other individuals to specialize in virtual reality treatments. Clinicians also thought virtual reality would be an important tool for veterans who were avoidant or had difficulty engaging in imaginal exposure therapy, although they thought virtual reality would be clinically contraindicated among veterans with comorbid conditions, substance abuse, complex trauma, or personality disorders. Clinicians said that older veterans may be less willing to engage in interventions using computers, headgear, and other hardware.

Organizational factors were more readily discussed in the treatment groups compared with the assessment groups. Clinicians recommended modifications to VHA productivity standards in order to facilitate implementation and use of virtual reality technology, but they were also concerned that the current demand for services would prevent changes in these standards. Clinicians viewed virtual reality therapy as consistent with the VA mission, which would ultimately facilitate implementation, but expressed concern about the resources needed for equipment, software, training, and ongoing technical assistance.

Clinicians were also concerned about the effects of virtual reality technology on the therapeutic relationship. They stated that multitasking (running software and monitoring computer screens while attending to the veteran) might ultimately interfere with the therapeutic alliance. They also thought that veterans would be more likely to accept virtual reality as a therapy if it was offered in the context of a trusting, therapeutic relationship.

Discussion and conclusions

Dissemination processes for new technologies in mental health care have been examined, and multiple barriers and facilitators have been identified, including characteristics of the adopting provider, organization, consumer, and intervention itself ( 8 , 9 , 10 ). The results from this study confirm the appropriateness of examining these categories for virtual reality. Our findings also confirm that use of this technology will face many challenges in the VHA that are similar to those that emerged in the focus groups.

We acknowledge that several factors may limit generalizability of this study, including the small sample from only one facility, clinicians' limited experience with the technology, and the lack of comparative data about implementation of other psychotherapies in the VHA. However, the multiple and diverse barriers and facilitators will likely provide valuable guidance on use of virtual reality for assessing and treating veterans.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Clinical Science Research and Development Merit Review grant 06S-VANIMH-01 and VA Health Services Research and Development Service grant MNH 98-000.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Seal KH, Bertenthal D, Maguen S, et al: Getting beyond "Don't ask; don't tell": an evaluation of US Veterans Administration postdeployment mental health screening of veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. American Journal of Public Health 98:714–720, 2008Google Scholar

2. Milliken CS, Auchterlonie JL, Hoge CW: Longitudinal assessment of mental health problems among active and reserve component soldiers returning from the Iraq war. JAMA 298:2141–2148, 2007Google Scholar

3. Rothbaum BO, Hodges L, Alarcon R, et al: Virtual reality exposure therapy for PTSD Vietnam veterans: a case study. Journal of Traumatic Stress 12:263–271, 1999Google Scholar

4. Rizzo A, Reger G, Gahm G, et al: Virtual reality exposure therapy for combat related PTSD; in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Basic Science and Clinical Practice. Edited by Shiromani PJ, Keane TM, LeDoux JE. Totowa, NJ, Human Press, 2009Google Scholar

5. Rothbaum BO, Hodges LF, Ready D, et al: Virtual reality exposure therapy for Vietnam veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 62:617–622, 2001Google Scholar

6. Wood DP, Murphy J, Center K, et al: Combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder: a case report using virtual reality exposure therapy with physiological monitoring. Cyberpsychology and Behavior 10:309–315, 2007Google Scholar

7. Cahill SP, Foa EB, Hembree EA, et al: Dissemination of exposure therapy in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress 19:597–610, 2006Google Scholar

8. Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, et al: Implementation Research: A Synthesis of the Literature. Tampa, University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, 2005Google Scholar

9. Henderson JL, MacKay S, Peterson-Badali M: Closing the research-practice gap: factors affecting adoption and implementation of a children's mental health program. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology 35:2–12, 2006Google Scholar

10. Schoenwald SK, Hoagwood K: Effectiveness, transportability, and dissemination of interventions: what matters when? Psychiatric Services 52:1190–1197, 2001Google Scholar