Estimating Lost Revenue From a Free-Care Mandate in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

Care at U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities is free for a variety of service-related conditions and disabilities. Individual veterans can apply for a service-connected disability rating from 0% to 100% based on ailments caused or exacerbated by military service. Copayments for outpatient visits are waived for care related to a veteran's service-connected condition or if the veteran has a compensable service-connected disability. They are also waived if personal income falls below a specified level. There is no cost for care related to exposure to Agent Orange or nasopharyngeal radium treatment among certain veterans, and former prisoners of war and Purple Heart medal recipients are categorically exempt from copayments for selected types of care.

Since 1995 copayments have not been required for outpatient treatment related to military sexual trauma. The VA defines military sexual trauma as sexual assault or harassment during military service ( 1 ). Approximately 20% of females and 1% of males in the VA health care system have experienced it. Individuals who screen positive for military sexual trauma have significantly elevated rates of a wide range of mental and physical disorders ( 2 , 3 ).

Even small increases in copayments have been tied to decreases in the use of VA services ( 4 , 5 ). Congress eliminated the copayment for care related to military sexual trauma among veterans who screened positive in order to reduce the financial barrier to treatment. Yet eliminating copayments reduces income of the VA system. The potential loss is substantial because more than 70,000 VA users had screened positive for military sexual trauma by fiscal year (FY) 2006 ( 6 ). Although Congress could replace the lost funds in the VA's annual appropriation, the actual cost of free-care mandates is unknown.

Here we present results of a retrospective analysis of administrative and clinical data in the VA. Our goal was to estimate the copayment revenue that the VA forgoes due to the mandate for free care for military sexual trauma. The process illustrates how VA leaders considering future free-care mandates can easily estimate their likely financial impact using data accessible within the agency.

Methods

We studied outpatient care provided in VA facilities in FYs 2006–2008 (October 1, 2005–September 30, 2008). VA Medical SAS Outpatient Datasets provided information on patient demographic and clinical characteristics for each outpatient encounter that a provider designated as relating to military sexual trauma ( 7 ). (An encounter is any direct provider-patient interaction.) Cost figures are reported in 2008 dollars. Inflation adjustment was done using the Consumer Price Index.

Copayment status was determined for each individual having an encounter related to military sexual trauma. The Medical SAS Outpatient Datasets contain a variable (MEANS) that reflects a test of the person's financial means. The MEANS variable has seven values: two specify that copayments are not required, two specify that they are required, and three indicate that a financial means test does not apply or was not done. The financial means test is not required for those who are exempt from copayments for other reasons and for military personnel who have not yet been discharged from active duty. We defined copayment-exempt individuals as those listed in the categories of exempt, not applicable, and not done. We chose the copayment status of the first encounter of the year for the treatment of military sexual trauma to apply to all visits during that year. Copayment status could change across years.

During the study period there were two copayment levels, $15 for primary care and $50 for specialty care. Inflation adjustment raised them slightly in FY 2006 and FY 2007. We assigned the proper copayment based on the type of clinic (primary or specialty) at which an encounter occurred. We then developed the average copayment across all encounters in each year for each sex.

Copayments collected from patients, third-party payers, and other sources constitute the Medical Care Collections Fund (MCCF) ( 8 ). We present descriptive statistics on the number of unique patients and visits, the weighted average copayment, and the proportion who would make copayments in the absence of the free-care mandate. From these we estimated the total copayments forgone due to the mandate and the proportion of that total out of annual MCCF collections from patients for outpatient care.

Results are presented separately by sex and year. Race and ethnicity was not studied because of incomplete coding in VA data. All analyses were performed in SAS, version 9.1. The Stanford University Institutional Review Board approved this study and waived the requirement for informed consent.

Results

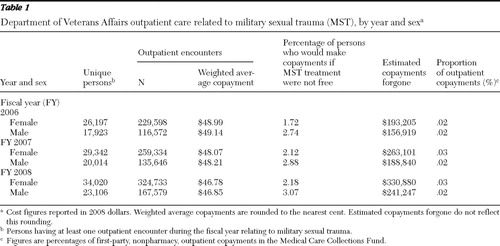

Results are shown in Table 1 . The number of unique individuals with outpatient encounters related to military sexual trauma rose from 44,120 in FY 2006 to 57,126 in FY 2008. Women had the majority of these encounters. The proportion of care provided in specialist settings rose slightly across years, from 88.4% in FY 2006 to 90.9% in FY 2008. The weighted average copayment ranged from $47 to $49 in 2008 dollars.

|

The proportion of people who would make copayments in the absence of the free-care mandate for military sexual trauma was very low, 1.7%–3.0% across gender and year categories. The estimated copayment revenue forgone by the free-care mandate for military sexual trauma was modest, totaling $418,244 in FY 2006, $516,696 in FY 2007, and $454,524 in FY 2008. These totals represented only .01%–.04% of MCCF first-party copayment revenues for outpatient care ( 9 , 10 ).

Discussion

Our results suggest that VA medical centers are providing free care for military sexual trauma without a significant loss of copayment revenue. A key driver of copayment revenue is the mixture of differing levels of service-connected disability among individuals receiving the treatments in question. The more the treatments are received by persons with low income or high levels of service-connected disability, the smaller the potential loss of copayments from a free-care mandate. In the case of military sexual trauma, about 35% of men and 44% of women in the study population qualified for free care through a service-connected disability rating of 50% or greater. The remainder had sufficiently low income to have copayments waived or received care related to military sexual trauma that also pertained to a service-connected disability.

The incentive effect of a free-care mandate may depend on many factors beyond a copayment exemption. They could include patients' perceptions of treatment efficacy, scheduling convenience, and other costs associated with treatment, such as transportation and the value of personal time. Research into these factors would be needed to assess the relative importance of a free-care mandate from the patient perspective.

We note several limitations. Our analysis is from the perspective of the VA, so it does not capture the full societal cost of the mandate. We have excluded contract care purchased for VA enrollees from outside providers. In unreported results we found that contract care for people screening positive for military sexual trauma was very rare in FY 2006. Contract care is growing, however, and future research could investigate it again. A third limitation is that VA providers must decide whether to indicate that an encounter pertained to military sexual trauma, and there may be inconsistency in their manner of doing so. We have also assumed that the free-care mandate did not stimulate additional use of VA services. Finally, the impact of the free-care mandate for military sexual trauma may not generalize to other conditions.

Conclusions

Since 1995 public law has mandated that outpatient encounters related to military sexual trauma are delivered free of charge. Although these individuals together account for more than 345,000 related encounters each year, the actual forgone copayment revenue is quite low because roughly 97% of the individuals would not face a copayment even without the mandate.

Estimating the revenue loss from a free-care mandate is straightforward in the VA. Researchers and managers alike can access national administrative data on the use and cost of services. System-level financial figures, such as MCCF collections, are publicly available ( 9 , 10 ,11). Figuring forgone income could easily be integrated into analysis of new mandates.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors received funding from grant IAE 05-291 from the VA Health Services Research and Development Service. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the VA.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Kimerling R, Gima K, Smith MW, et al: The Veterans Health Administration and military sexual trauma. American Journal of Public Health 97:2160–2166, 2007Google Scholar

2. Frayne SM, Skinner KM, Sullivan LM, et al: Medical profile of women Veterans Administration outpatients who report a history of sexual assault occurring while in the military. Journal of Women's Health and Gender Based Medicine 8:835–845, 1999Google Scholar

3. Hankin CS, Skinner KM, Sullivan LM, et al: Prevalence of depressive and alcohol abuse symptoms among women VA outpatients who report sexual harassment while in the military. Journal of Traumatic Stress 12:601–612, 1999Google Scholar

4. Doshi JA, Zhu J, Lee BY, et al: Impact of a prescription copayment increase on lipid-lowering medication adherence in veterans. Circulation 119:390–397, 2009Google Scholar

5. Stroupe KT, Smith BM, Lee TA, et al: Effect of increased copayments on pharmacy use in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Medical Care 45:1090–1097, 2007Google Scholar

6. The MST Support Team: Military Sexual Trauma Screening Report. Washington, DC, Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health Services, 2006Google Scholar

7. Veterans Affairs Information Resource Center: VIReC Research User Guide: VHA Medical SAS Outpatient Datasets FY2006. Hines, Ill, Edward J Hines Jr VA Hospital, Sept 2007Google Scholar

8. Budget of the United States Government: Fiscal Year 2008: Appendix: Veterans Health Administration. Washington, DC, Office of Management and Budget. Available at www.gpoaccess.gov/usbudget/fy08 Google Scholar

9. FY 2008 Budget Submissions. Washington, DC, US Department of Veterans Affairs, 2008. Available at www4.va.gov/budget/products.asp Google Scholar

10. FY 2009 Budget Submissions. Washington, DC, US Department of Veterans Affairs, 2009. Available at www4.va.gov/budget/products.asp Google Scholar