Recovery From Disability for Individuals With Borderline Personality Disorder: A Feasibility Trial of DBT-ACES

Recovery is a central goal of the President's New Freedom Commission for Mental Health, defined in their report as "The process in which people are able to live, work, learn, and participate fully in their communities. For some individuals, recovery is the ability to live a fulfilling and productive life despite a disability. For others, recovery implies the reduction or complete remission of symptoms" ( 1 ). Treatment providers, then, are charged with the task of providing treatments that both reduce client symptoms and improve their functioning and quality of life despite symptoms.

Borderline personality disorder is a mental illness for which such normative life expectations are often considered lofty goals, especially when the individual is psychiatrically disabled. Psychiatric hospitalization is five times more likely for individuals with borderline personality disorder than for those with major depression ( 2 ), and many high utilizers of inpatient psychiatric care are diagnosed as having borderline personality disorder ( 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ). However, standard community treatments ( 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ) and commonly prescribed pharmacological treatments ( 10 ) are at best marginally effective for individuals with borderline personality disorder.

In contrast, there is evidence for the effectiveness of a number of psychotherapy interventions. Of these, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) has received the most empirical support across multiple randomized and nonrandomized controlled trials. DBT has been shown to reduce problem behaviors and improve the functioning of individuals with borderline personality disorder, as well as to increase their retention in treatment and decrease their use of emergency rooms and inpatient units. Randomized and nonrandomized studies of standard DBT (SDBT) and adaptations have largely replicated the initial results ( 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ).

Randomized controlled trials have shown that other types of interventions are also effective for treating borderline personality disorder. One randomized trial showed that mentalization-based partial hospitalization was more effective than usual care in reducing self-reported and clinically significant problems, including suicide attempts and hospitalization ( 28 , 29 ). Another randomized trial showed that patients who received schema-focused therapy were more likely to show reliable clinical improvement than patients who received transference-focused psychotherapy ( 30 ). In addition, a randomized comparison of transference-focused psychotherapy, DBT, and dynamic supportive psychotherapy found that all groups showed improvement, although transference-focused psychotherapy and DBT were more effective for suicidality, transference-focused psychotherapy and supportive psychotherapy were more effective for anger and impulsivity, and transference-focused psychotherapy was more effective for irritability and assault ( 31 ).

Harborview Mental Health Services (HMHS) was one of the first sites to implement DBT in the early 1990s, and HMHS has demonstrated outcomes for psychiatrically disabled individuals with borderline personality disorder comparable to those found in research trials ( 32 ). However, despite our successes, many of our patients with borderline personality disorder remained at HMHS without working or attending school and continued receiving public mental health services. DBT-Accepting the Challenges of Exiting the System (DBT-ACES) was developed at HMHS as a second year of treatment to address these issues. This article presents results from our pre-post program evaluation of DBT-ACES. We had four main hypotheses. We hypothesized that there would be a significant improvement in competitive employment and enrollment in college or vocational training as well as hours worked, a substantial decrease in the number of clients enrolled in the public mental health system following completion of DBT-ACES, a significant improvement in participants' subjective rating of quality of life, and a significant decrease in self-inflicted injury and in emergency and inpatient admissions.

Methods

This study was conducted in HMHS, an outpatient public mental health center that is part of Harborview Medical Center, the county hospital for Seattle and King County, Washington.

DBT-ACES participants were drawn from 85 patients aged 18 or older consecutively enrolled into the HMHS SDBT program between April 2000 and June 2005. A majority of the patients in this program received Medicaid, Medicare, or both (N=79, 93%). Participants entering SDBT were severely impaired, as characterized by repeated suicide attempts and multiple psychiatric hospitalizations and by a DSM-IV-TR Global Assessment of Functioning score that was less than 30. Thirty-seven clients (44%) dropped out of treatment during SDBT, and two participants died during SDBT (one of suicide and one whose death was ruled accidental, although suicide was possible). In addition to these 46 completers, three clients who completed SDBT in other clinics were also admitted into DBT-ACES. [A figure showing a CONSORT flowchart of study recruitment and completion is available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline.org .]

Clients are eligible to enroll in SDBT even if they do not have any interest in or plan for returning to work. DBT-ACES, however, requires that clients want to work, want to leave public mental health services, and are sufficiently stable (that is, no suicidal behavior or ideation and better than 75% treatment attendance and adherence for the past eight weeks). Seven of the 46 clients (15%) who completed SDBT at HMHS were not sufficiently stable to proceed to DBT-ACES, and nine (20%) were sufficiently stable but chose not to participate in DBT-ACES. Three DBT-ACES clients were not included in this evaluation: one made violent threats against the therapist, which required termination of contact, and two did not volunteer to participate in our study.

The study presented here evaluated the remaining 30 participants, all of whom gave voluntary informed consent for their responses to be included in published research. Data on clinical characteristics and outcomes were collected before and after SDBT for all participants, except for the three who came from other programs. All clients (except for two) kept in contact with the clinic after discharge from DBT-ACES, so data on work and follow-up treatment were able to be collected. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

At intake, the 30 DBT-ACES participants ranged in age from 19 to 56 and had a mean±SD age of 37±11 years. Twenty-four (80%) were women, and 30 (100%) were Caucasian, one of whom was Latina (3%). Nineteen (63%) were single or never married, nine (30%) were divorced, one (3%) was married, and one (3%) was separated. Four (13%) were currently living with a romantic partner. The highest education level varied: two (7%) had some high school, ten (33%) had their GED or high school diploma, six (20%) had some college, ten (33%) had graduated from college, and two (7%) had completed graduate school. Twenty-four (80%) of the sample were living independently, 11 (37%) had children, three (10%) were working at intake, and none had been arrested or jailed in the past year.

Using standard clinical procedures, the team psychiatrist assigned up to three axis I and one axis II diagnoses to the clinical record. The following diagnoses were made for participants: 29 (97%) had borderline personality disorder, one (3%) had schizotypal personality disorder, 17 (57%) had major depressive disorder without psychotic features, two (7%) had major depressive disorder with psychotic features, two (7%) had bipolar affective disorder, one (3%) had schizoaffective disorder (depressed type), two (7%) had dysthymia, one (3%) had substance abuse, four (13%) had substance dependence in remission, 11 (37%) had posttraumatic stress disorder, five (17%) had panic disorder, three (10%) had obsessive-compulsive disorder, four (13%) had generalized anxiety disorder, one (3%) had an eating disorder not otherwise specified, and one (3%) had Tourette's disorder.

Treatment phase 1: SDBT

All participants received one year of SDBT. The structure, treatment strategies, and protocols of SDBT are described in two DBT treatment manuals ( 33 , 34 ). SDBT was provided in this study with a few modifications that have been described elsewhere ( 32 ).

Treatment phase 2: DBT-ACES

DBT-ACES is an expansion and adaptation of DBT designed to meet the needs of psychiatrically disabled individuals with stabilized borderline personality disorder ( 35 ). (A manual on DBT-ACES is available upon request from the first author.) Clients attend both individual therapy and a weekly skills group for one year. DBT-ACES individual therapy uses exposure-based and contingency management procedures to block avoidance behaviors and reinforce progress toward recovery goals. These include graduated requirements of ten and then 20 hours of paid work or enrollment in college or vocational training with due dates at four and eight months, respectively, into DBT-ACES. If they are not met, clients are given a "vacation from therapy" until the requirement (either ten or 20 hours) is met for at least one week. This forms a series of deadlines that are a key contingency management strategy in DBT-ACES. In the DBT-ACES skills group, the curriculum focuses on DBT skills, as well as goal setting; problem solving; reinforcement; dialectical thinking; reducing perfectionism, anger, depression, and anxiety; and strategies for working effectively with health care providers.

DBT-ACES is not like supported employment or other vocational rehabilitation models in that DBT-ACES therapists do not help the clients with their job search process. Although such help is useful to clients and referrals to vocational rehabilitation are made if needed, most clients in the program successfully find and apply for jobs on their own. Fundamentally, the primary issue for most DBT-ACES clients is severe anxiety, shame, and anger, as well as poor problem-solving and interpersonal skills. These cause clients to avoid pursuing employment or impair their behavior on the job. Traditional vocational service providers, seeing the extreme emotions exhibited by clients with borderline personality disorder, often encourage a slower process toward work when clients show emotional volatility, which reinforces avoidance and fear of working. By contrast, the DBT psychotherapeutic strategies target emotion regulation and problem-solving deficits directly while the client seeks and attends employment.

DBT-ACES clients are encouraged to leave the public mental health system because the primary community mental health interventions (medication and case management) have generally not been effective for borderline personality disorder, because many of our clients report better outcomes with no treatment or with psychotherapy specific to an axis I diagnosis, and because publicly funded services in Washington State are not available for persons who work a substantial amount.

Measures

An abbreviated version of the Quality of Life Interview (QOLI) ( 36 ) was used to assess the primary outcome variables: competitive employment (that is, employment in integrated work settings among workers without disabilities and for which the client was paid by the employer wages equal to the wages paid to other workers doing the same or similar jobs) and school attendance (that is, being a matriculated student). The average of the two general life satisfaction ratings from the QOLI was used to determine subjective satisfaction. The QOLI was developed specifically for severely and persistently ill populations and has been shown to have strong psychometric properties.

The use of medical, behavioral health, and crisis services and the presence of medically treated self-inflicted injuries were assessed by the Treatment History Interview (THI). Previous analyses of THI data showed high reliability compared with medical records and therapist report.

Procedures

Program evaluation interviews were conducted at the point of participants' initial enrollment in SDBT, the end of SDBT, the end of DBT-ACES, and one year after discharge from DBT-ACES. The first and second authors trained and supervised the bachelor's-level interviewers, and each interview was checked for accuracy before data entry. All clients who attended at least one session of DBT-ACES were followed for assessments, regardless of whether they dropped out from treatment. Participants did not receive monetary compensation for their participation during treatment, but those who had dropped out or graduated were paid $25 for follow-up interviews.

Data analysis

Descriptive data are presented from baseline (that is, before SDBT) through one year after DBT-ACES, but the primary focus of statistical analysis is change from the end of SDBT through the end of DBT-ACES and through one year after the end of DBT-ACES. Data were analyzed using random-effects regression models (RRMs) ( 37 ) to account for the repeated-measures nature of the data. Because the change across time was not linear, two separate analyses compared the change from the end of SDBT to the end of DBT-ACES and from the end of SDBT to one year after the end of DBT-ACES.

Six primary outcomes were analyzed using RRMs (and variable type): employment or school status (binary), 20 or more hours of work per week (binary), overall life satisfaction (continuous), emergency room admissions (count), inpatient psychiatry admissions (count), and medically treated self-inflicted injuries (count). Binary outcomes were analyzed using logistic RRMs, count outcomes were analyzed using overdispersed Poisson RRMs, and life satisfaction was analyzed using a standard RRM that assumes normally distributed residuals. In each analysis, the baseline value of the outcome was used as a covariate. All analyses were done using R, version 2.9.1 (R Development Core Team).

Results

Twenty-four of the 30 participants who started DBT-ACES completed the program (80%), and six (20%) dropped out. Persons who dropped out received a mean of 6.8±2.9 months of treatment, with a range of two to 11 months.

Employment and school

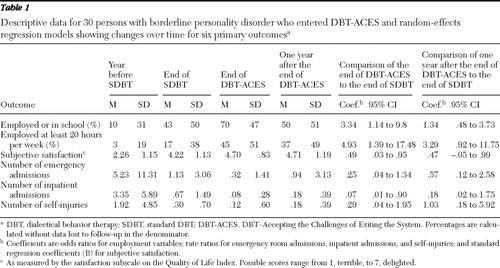

Table 1 includes descriptive data as well as the measurements of change from the end of SDBT to the end of DBT-ACES and from the end of SDBT to one year after DBT-ACES. Our first hypothesis was that clients would show significant improvement in paid employment or attendance in a college or vocational program. As shown in Table 1 , logistic RRM indicated a significant improvement in participants' odds of being employed or in school between the end of SDBT and the end of DBT-ACES (odds ratio [OR]=3.34, p<.05). One year after DBT-ACES, gains were reduced somewhat, and there was no significant difference from the end of SDBT to one year after the end of DBT-ACES. The odds of working 20 or more hours increased significantly following DBT-ACES (OR=4.93, p=.01), and gains were mostly retained in the year after DBT-ACES, although the findings were not significant (OR=3.29, p=.06).

|

DBT-ACES participants found work in a variety of occupations, including retail, elder care, child care, art, tutoring, office work, marketing, project management, teaching, house cleaning, case management, service coordination, and cosmetology. Of the six participants who enrolled in school while they were participating in DBT-ACES, half were in college (N=3, 50%) and the other half were in a vocational technical school or program (N=3, 50%). We also evaluated clients' reasons for not working. Almost half (N=4 of 9, 45%) of participants who were not working at the end of SDBT reported they were not working primarily for psychiatric reasons, which declined to one (7%) at the end of DBT-ACES and remained at one (7%) at the end of the year after DBT-ACES. The remaining participants who were not working at the end of SDBT (N=5, 55%) reported that unemployment was due to physical problems, not finding a job, or other reasons, such as attending school.

Enrollment in the public mental health system

Our second hypothesis was that there would be a substantial number of clients who had left the public mental health system by one year after the end of DBT-ACES. Eighteen of 28 clients for whom this datum was available (64%) had left the public mental health system one year after the end of DBT-ACES and were receiving private, low-income, or no mental health services.

Quality of life

Our third hypothesis was that overall quality of life would significantly improve. Table 1 shows participants' ratings of overall quality of life on the satisfaction subscale of the QOLI ( 36 ). The RRM showed significant improvement from the end of SDBT to the end of DBT-ACES (B=.49, p=.03), which was mostly retained one year after DBT-ACES (B=.47, p=.08).

Admissions and medically treated self-injuries

Finally, we hypothesized that participants would show a reduction in emergency room admissions for psychiatric reasons, inpatient psychiatry admissions, and medically treated self-inflicted injuries. As shown in Table 1 , the most dramatic improvements in these variables occurred after SDBT. Overdispersed Poisson RRMs revealed that at the end of DBT-ACES and in the year after DBT-ACES almost all rate ratios were less than one (indicative of further improvement), although the only significant finding was a reduction in inpatient admissions between the end of SDBT and the end of DBT-ACES (rate ratio=.07, p<.05). These results indicate that the substantial improvements made during SDBT on core DBT targets were not lost during DBT-ACES or in the year after DBT-ACES.

Discussion

This study evaluated the feasibility and utility of DBT-ACES, an adaptation of DBT created to end dependency on social services. Over time, participants were more likely to be employed and to be employed for more hours. It was also encouraging to see that a majority of those employed were able to earn enough to be above the poverty line, which was $847 per month for a single person according to the 2006 U.S. Census. In addition, a majority of participants in this study had left the public mental health system one year after graduating from DBT-ACES, and quality of life improved significantly between the end of SDBT and the end of DBT-ACES. Although there was a decline in most outcomes in the year after DBT-ACES, DBT treatment was not provided during that time, and a majority of participants continued working and many increased the number of hours worked per week.

Returning to work can be very stressful for clients. DBT-ACES clients often showed an increase in symptoms and even substantial distress as a deadline for beginning or increasing work neared (when they would have to go on a "therapy vacation" if they did not meet these deadlines). However, that contingency motivated them to persist. Once working, a majority of DBT-ACES clients reported that working was less stressful than they thought it would be and that it was less stressful than finding and maintaining social services. This suggests the importance of such a contingency in helping clients with borderline personality disorder return to work.

Twenty-four (80%) clients who started DBT-ACES completed the program, whereas six (20%) did not. Although these samples were too small for subgroup analysis, visual examination of the outcomes indicated worse outcomes for dropouts than for completers, particularly in the percentage still working at the final assessment (13 completers, or 54%, versus one dropout, or 17%).

DBT-ACES was designed as a follow-up treatment after completion of SDBT, and thus the explicit focus on employment does not begin until participants have been in treatment a full year. This is in contrast to rapid placement strategies in other vocational models such as supported employment. In addition, the relatively high employment rate at the end of SDBT suggests that employment interventions could start earlier. Our current research is evaluating whether and how DBT-ACES interventions can be started while SDBT is ongoing.

There were a number of important limitations in this study. First, this sample was limited to those with a history of severe borderline personality disorder who wanted to work and recover from disability and who had successfully stabilized after a year of standard DBT (only 32% of those who started SDBT). DBT-ACES is designed for those who have completed SDBT, because it depends on competence with DBT skills as well as stability and motivation to work. This selection bias means that these results cannot be generalized to all individuals in the public mental health system with severe borderline personality disorder nor to those who have stabilized their disorder but do not want to work or recover from disability. Second, the sample was quite small and ethnically homogeneous. Finally, there was no comparison condition, so it is possible that these individuals would have made these improvements with usual care or time alone.

Conclusions

In conclusion, DBT-ACES is for psychiatrically disabled clients who have stabilized their borderline personality disorder and want to recover from disability. From the end of SDBT to the end of DBT-ACES participation, the program was significantly associated with increased productivity, employment, and quality of life and with decreased inpatient admissions. From the end of SDBT to one year after the end of DBT-ACES, some gains were retained, although they were no longer statistically significant. Although the lack of a control condition or randomization precludes causal interpretations, we believe that regardless of cause, demonstrating that psychiatrically disabled clients with stabilized borderline personality disorder can achieve these outcomes after completing DBT-ACES is important in its own right.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported in part by a grant from the Catherine Holmes Wilkins Foundation. The authors acknowledge the contribution of the HMHS Dialectical Behavior Therapy therapists, who together developed DBT-ACES (Marty Hoiness, M.D., Kristina Huus, L.M.H.C., JoAnn Marsden, R.T., Cristina Mullen, L.I.C.S.W., and Wayne Smith, Ph.D.), and Marsha Linehan, Ph.D., for her support and keeping the authors true to DBT. The authors also thank the clients of DBT-ACES for their willingness and commitment to DBT-ACES as well as their feedback, which substantially improved the treatment.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America: Final Report. DHHS pub no SMA-03-3832. Rockville, Md, Department of Health and Human Services, New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003Google Scholar

2. Bender DS, Dolan RT, Skodol AE, et al: Treatment utilization by patients with personality disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:295–302, 2001Google Scholar

3. Swigar ME, Astrachan B, Levine MA, et al: Single and repeated admissions to a mental health center: demographic, clinical and use of service characteristics. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 37:259–266, 1991Google Scholar

4. Geller JL: In again, out again: preliminary evaluation of a state hospital's worst recidivists. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 4:386–390, 1986Google Scholar

5. Widiger TA, Weissman MM: Epidemiology of borderline personality disorder. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:1015–1021, 1991Google Scholar

6. Surber RW, Winkler EL, Monteleone M, et al: Characteristics of high users of acute psychiatric inpatient services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:1112–1114, 1987Google Scholar

7. Woogh CM: A cohort through the revolving door. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 31:214–221, 1986Google Scholar

8. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, et al: Mental health service utilization by borderline personality disorder patients and axis II comparison subjects followed prospectively for 6 years. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65:28–36, 2004Google Scholar

9. Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Gunderson JG, et al: Two-year stability and change of schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 72:767–775, 2004Google Scholar

10. Binks CA, Fenton M, McCarthy L, et al: Pharmacological interventions for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database System Review: CD005653, 2006Google Scholar

11. Kelly T, Soloff PH, Cornelius J, et al: Can we study (treat) borderline patients? Attrition from research and open treatment. Journal of Personality Disorders 6:417–433, 1992Google Scholar

12. Tucker L, Bauer SF, Wagner S, et al: Long-term hospital treatment of borderline patients: a descriptive outcome study. American Journal of Psychiatry 144:1443–1448, 1987Google Scholar

13. Perry JC, Cooper SH: Psychodynamics, symptoms, and outcome in borderline and antisocial personality disorders and bipolar type II affective disorder; in The Borderline: Current Empirical Research. Edited by McGlashan TH. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1985Google Scholar

14. Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, et al: Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:1060–1064, 1991Google Scholar

15. Koons C, Chapman A, Betts B, et al: Dialectical behavior therapy adapted for the vocational rehabilitation of significantly disabled mentally ill adults. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 13:146–156, 2006Google Scholar

16. Linehan MM, Heard HL, Armstrong HE: Naturalistic follow-up of a behavioral treatment for chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:971–974, 1993Google Scholar

17. Linehan MM, Tutek DA, Heard HL, et al: Interpersonal outcome of cognitive behavioral treatment for chronically suicidal borderline patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:1771–1776, 1994Google Scholar

18. Linehan MM, Schmidt H III, Dimeff LA, et al: Dialectical behavior therapy for patients with borderline personality disorder and drug-dependence. American Journal of Addictions 8:279–292, 1999Google Scholar

19. Koons CR, Robins CJ, Tweed JL, et al: Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy in women veterans with borderline personality disorder. Behavior Therapy 32:371–390, 2002Google Scholar

20. Linehan MM, Dimeff LA, Reynolds SK, et al: Dialectical behavior therapy versus comprehensive validation plus 12-step for the treatment of opioid dependent women meeting criteria for borderline personality disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 67:13–26, 2002Google Scholar

21. Verheul R, van den Bosch L, Louise MC, et al: Dialectical behaviour therapy for women with borderline personality disorder: 12-month, randomised clinical trial in the Netherlands. British Journal of Psychiatry 182:135–140, 2003Google Scholar

22. Van den Bosch LMC, Koeter MWJ, Stijnen T, et al: Sustained efficacy of dialectical behaviour therapy for borderline personality disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy 43:1231–1241, 2005Google Scholar

23. Turner RM: Naturalistic evaluation of dialectical behavior therapy-oriented treatment for borderline personality disorder. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 7:413–419, 2000Google Scholar

24. Lynch TR, Morse JQ, Mendelson T, et al: Dialectical behavioral therapy for depressed older adults: a randomized pilot study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 11:33–45, 2003Google Scholar

25. Rathus JH, Miller AL: Dialectical behavioral therapy adapted for suicidal adolescents. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 32:146–157, 2002Google Scholar

26. Bohus M, Haaf B, Stiglmayr C, et al: Evaluation of inpatient dialectical-behavioral therapy for borderline personality disorder: a prospective study. Behaviour Research and Therapy 38:875–887, 2000Google Scholar

27. Comtois KA, Elwood L, Holdcraft LC, et al: Effectiveness of dialectical behavioral therapy in a community mental health center. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 14:406–414, 2007Google Scholar

28. Bateman A, Fonagy P: Effectiveness of partial hospitalization in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1563–1569, 1999Google Scholar

29. Bateman A, Fonagy P: Partial hospitalization for borderline personality disorder: in reply to R. Stern. (Letter to the editor). American Journal of Psychiatry 158:1932–1933, 2001Google Scholar

30. Giesen-Bloo J, van Dyck R, Spinhoven P, et al: Outpatient psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: randomized trial of schema-focused therapy vs transference-focused psychotherapy. Archives of General Psychiatry 63:649–658, 2006Google Scholar

31. Clarkin JF, Levy KN, Lenzenweger MF, et al: Evaluating three treatments for borderline personality disorder: a multiwave study. American Journal of Psychiatry 164:922–928, 2007Google Scholar

32. Comtois KA, Elwood L, Holdcraft LC, et al: Effectiveness of dialectical behavioral therapy in a community mental health center. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 14:406–414, 2007Google Scholar

33. Linehan MM: Skills Training Manual for Treating Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, Guilford, 1993Google Scholar

34. Linehan MM: Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, Guilford, 1993Google Scholar

35. Comtois KA, Huus K, Hoiness M, et al: Dialectical Behavior Therapy: Accepting the Challenges of Exiting the System (DBT-ACES) Treatment Manual, Distribution Version 10-06. Seattle, Wash, Harborview Medical Center, University of Washington, 2006Google Scholar

36. Lehman AF: A Quality of Life Interview for the mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning 11:51–62, 1998Google Scholar

37. Hedeker D, Gibbons R: Longitudinal Data Analysis. New York, Wiley, 2006Google Scholar