Web-Based Psychoeducational Intervention for Persons With Schizophrenia and Their Supporters: One-Year Outcomes

Because treatments that have proved efficacious in academic settings over the past 30 years have rarely been adopted by community agencies ( 1 , 2 ), there is a need to develop ways to translate and disseminate useful programs to community settings. One such treatment is family psychoeducation ( 3 , 4 , 5 ). The results of more than 30 experimental trials have established family psychoeducation as an evidence-based practice ( 6 , 7 ) routinely recommended as the gold standard for care of persons and families coping with schizophrenia ( 1 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ). However, results from the seminal Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team study showed that although 77% of those with schizophrenia live with or have ongoing contact with their families, only a small proportion have an outpatient claim for any family intervention (<1% Medicare and 7% Medicaid) ( 2 ). These data led us to design a randomized feasibility trial of an adapted telehealth family psychoeducational intervention provided to users' homes to increase community dissemination.

Online interventions have the potential to overcome several barriers to dissemination and community care for persons with serious mental illness, including the limited number of persons with schizophrenia in some clinics, the high costs of training staff and delivering evidence-based programs, the difficulty of monitoring fidelity, and the interpersonal and logistical difficulties involved with traveling to receive services. Telehealth services also allow individuals to take an active role in seeking information and support, to participate in group interactions, to learn specific skills, and to adjust participation as necessary. Thus the online method can facilitate the traditional treatment goals of symptom and burden reduction and facilitate the recovery goals of improved quality of life and personal goal attainment.

The strategies used in this "schizophrenia online access to resources" (SOAR) intervention were designed to provide key elements of family psychoeducation: empathic engagement of participants, education about the illness and treatments, a supportive safety net, and coping strategies. The interventions provided and the Web site's format were designed to be clear, accessible to persons with cognitive impairments ( 12 ), and visually nondistracting and low key to avoid an exacerbation of the illness-related vulnerabilities to stimulation that can trigger symptoms and relapse ( 8 , 13 ). Based on evidence suggesting the advantages of using a group model ( 14 ), we added supporter and peer discussion forums to SOAR.

SOAR teaches and engages participants in problem solving to decrease stress, meet personal needs, and achieve personal goals. Theoretical and empirical work indicates that meeting an individual's needs can reduce stress, promote better adaptation to illness-related difficulties, and improve outcomes ( 15 ), whereas when needs go unmet distress can increase and outcomes may worsen ( 16 ). In addition, through tutorials and self-help articles, the content on the SOAR site emphasizes promotion of self-efficacy, self-management, and problem solving ( 17 , 18 ). These themes were also emphasized in three therapy forums on the site, which encourage social support and social learning among participants ( 19 ).

Methods

This study was conducted from October 2003 to April 2005. A more detailed description of the methods and participants is available elsewhere ( 20 ).

Participant recruitment and selection criteria

Persons with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were recruited from community mental health centers and inpatient units. Enrollment criteria for persons with schizophrenia were age 14 or older, diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder ( DSM-IV criteria), one or more psychiatric hospitalizations or emergency department visits within the previous two years, the ability to speak and read English, living in the community at the time of study entry, and absence of physical limitations that would preclude using a computer. Enrollment criteria for support persons were age 18 or older, ability to speak and read English, and absence of physical limitations that would preclude using a computer. [Additional enrollment details are provided in an appendix available as an online supplement to this article at ps.psychiatryonline.org .] Informed consent was obtained from participants, and the research protocol was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Participants

Thirty-one persons with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and 24 support persons were randomly assigned to the telehealth or usual care condition.

Procedures

Participants assigned to the telehealth condition received dial-up Internet access and a computer as needed. Participants were in the study for up to one year (see online appendix for additional details).

SOAR Web site

Each intervention participant was given a unique login name and password to access SOAR. The SOAR software collected information on each participant's usage of the Web site, including the pages visited, time of day the site was visited, time spent on the site, and user identifier. (See the online appendix for greater detail about the content and design of the site.)

Content. Selection of the content domains and their creation are described elsewhere ( 12 , 20 ). The SOAR Web site provides the following components: three therapy forums, one for persons with schizophrenia only, one for support persons only, and one for both groups of users; a capability for asking questions of and receiving answers from the project team within 24–48 hours; a library of previously asked and answered questions; a library of educational reading materials; and a list of community activities, events, and resources.

Facilitation of therapy forums. Each forum was led and moderated by a therapist. In each forum the therapist emphasized discussions that focused on problem solving, alleviating stress, and interacting with peers to develop a supportive forum where members could work together to address problems ( 3 , 21 ).

Site design. SOAR was specifically designed to be accessible to persons with cognitive impairments, as detailed elsewhere ( 12 ). The design model is based on five key principles: use of explicit links and labels; a flat, one-page-deep hierarchy; a relatively high number of links on navigation pages; a single constant navigational toolbar; and minimal superfluous and distracting content, such as images.

Psychoeducation survival skills workshop

Before we installed computers in participants' homes and provided access to SOAR via a desktop icon, telehealth participants (persons with schizophrenia and their support persons) attended a joint, four-hour psychoeducation survival skills workshop. The course was modeled on a workshop developed by Dr. Anderson and her colleagues ( 3 ) and is described elsewhere ( 20 ).

Assessment instruments

Trained, nonblinded interviewers collected data from participants at study entry and at three, six, and 12 months postbaseline. (Additional details about assessment tools are provided in the online appendix.)

Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms. The 34-item Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms was used at all time points to assess for the presence and severity of positive symptoms associated with schizophrenia ( 22 ).

Knowledge About Schizophrenia Instrument. At baseline and at six months, the Knowledge About Schizophrenia Instrument was administered to assess participants' clinical knowledge about the illness ( 23 ).

Usage of the Web site. Server logs from October 2003 to April 2005 were analyzed to determine usage patterns and number of page views or hits. The time between accessing one page and viewing another was considered to be the amount of time that a page was available for viewing. For usage analyses, online time spent on educational activities included viewing reading materials, viewing the library of questions and answers, and submitting questions to be answered and viewing responses.

Data analytic plan

Intention-to-treat analyses were used to investigate the effects of the intervention versus usual care conditions on outcomes. The three-month data collected from one person with schizophrenia was deemed unreliable by the interviewer and was thus excluded from analyses. Mixed-effects random-intercept models characterized the rates of change over the course of the study, after analyses adjusted for baseline age, gender, and positive symptoms. These models used an autoregressive error structure most appropriate for longitudinal data ( 24 ) and used restricted maximum-likelihood estimate model parameters when data were missing ( 25 ).

The significance of treatment effects was examined by calculating two-tailed t tests of the beta weight for the mixed-model treatment × time interaction term, as is customary. Cohen's d was calculated from predicted means based on these models to estimate the magnitude of treatment effects on rates of changes to symptomatology (schizophrenia group) and knowledge (schizophrenia and support persons). In addition, within-group analyses of the associations between Web site usage and baseline symptomatology and knowledge outcomes were conducted within the intervention group using Pearson correlation coefficients to identify the correlates of the intervention. For symptomatology data collected at multiple follow-up periods, correlation coefficients were pooled across time to obtain an average estimate of the relations between symptomatology and amount of SOAR Web site usage. Positive symptom data were log-transformed because of substantial positive skew. No adjustments for multiple comparisons were made in this initial feasibility study of the intervention.

Results

Participants

Demographic characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 1 . Forty-eight percent of the sample with schizophrenia was Caucasian, and the average age in the group was 38. In the group of support persons, 46% were Caucasian, and their average age was 50. One patient (3%) and four family members (17%) dropped out of the study.

|

Use of the Web-based intervention

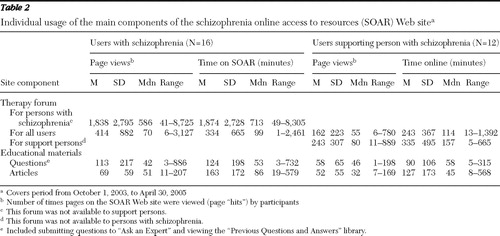

Persons with schizophrenia in the telehealth group. The total amount of time spent on the SOAR Web site by those in the schizophrenia group was 43,789 minutes (730 hours), which involved 47,630 page views. Over the course of the study, the average total time spent on the Web site per person was 46 hours, or 2,737±3,692 minutes (median=971, range=162–11,796), with an average of 2,977±4,546 page views (median=1,170, range=189–14,120) per person. Usage of the main components of the Web site is presented in Table 2 .

|

Support persons in the telehealth group. The total amount of time that support persons spent on the Web site over the period of observation was 10,901 minutes (182 hours) and involved 8,210 page views. The average total time spent on the Web site per person was 14 hours, or 839±1,125 minutes (median=372, range=30–4,021), with an average of 632±729 page views (median=253, range=19–2,498) per person. Support persons' usage of the main components of the Web site is presented in Table 2 .

Engagement in treatment

Although treatment engagement involves a complex set of processes ( 26 ), an established operational definition of successful initial engagement ( 27 , 28 , 29 ) is return for treatment after the intake session. To explore engagement in the online treatment environment, we considered attendance at the psychoeducation survival skills workshop as the intake session and defined participants as initially engaged if they subsequently participated at least once in one of the therapy forums and in educational activities. All persons with schizophrenia participated in a therapy forum on at least 13 separate visits, and they used educational resources on at least four visits. These results indicate that 100% of the participants with schizophrenia were engaged in their treatment.

Of the support persons, only one did not fully engage (participating once in each forum but not in educational activities). Of the other 12 support persons in the telehealth condition, all participated in a therapy forum on at least 11 visits and viewed articles on at least five visits, indicating that 12 (92%) were successfully engaged in treatment.

Ongoing Web site usage

Participants in the schizophrenia group had a total of 4,473 individual sessions or visits to the Web site, with a mean of 280±337 sessions per person (median=128, range=28–1,232). The persons with schizophrenia were active in the therapy forums during 3,200 sessions (72% of total sessions), with an average of 200±318 sessions per person (median=82, range=13–1,173). The average number of months in which each person was active in a therapy forum was 11±4 (median=11, range=4–17), where they spent an average of 3.2 hours per month or 193±316 minutes (median=64, range=14–1,193). Overall, these data indicate strong engagement of most participants in this part of the intervention.

Persons with schizophrenia participated in educational activities during 807 visits (18% of total visits), with an average 50±80 visits per participant (median=30, range=4–340). The average number of months in which each person viewed educational materials was 8±4 (median=8, range=3–16), spending an average of 32±26 minutes per month (median=24, range=7–88). These data suggest that online approaches to education, using materials specifically designed and written for this population, can be well received.

Support persons had a total of 972 sessions on the SOAR site, with an average of 75±59 sessions per person (median=57, range=1–207). They participated in a therapy forum during 539 visits (55% of total), with an average of 42±40 visits per person (median=19, range=1–129). The average number of months in which each support person was active in a therapy forum was 9±6 (median=7, range=1–19), and each spent an average of 55±43 minutes on the site per month (median=41, range=9–161). Support persons participated in educational activities during 339 visits (35% of total), averaging 26±29 visits per person (median=189, range=0–92) over an average of 7±6 months (median=6, range=0–18). They spent on average 29±42 minutes (median=17, range=0–160) during an active month. Support persons used the forum and educational components of SOAR frequently and over a sustained period, indicating that family and friends can become engaged by this approach to psychoeducation.

Outcomes

Analyses using mixed-effects random-intercept models indicated that compared with persons with schizophrenia who received usual care, their counterparts in the telehealth group had significant and large reductions ( 30 ) in positive symptoms during the treatment intervention (t=-2.06, df=97, p=.042, d=-.88) ( Figure 1 ). Using the same analytical methods, we found in the telehealth group a significant and large improvement in knowledge about the diagnosis of schizophrenia (t=-2.34, df=24, p=.028, d=.88) ( Figure 1 ). No effects were found on other domains of knowledge about schizophrenia. Analyses of the association between cumulative Web site usage and symptom severity indicated that individuals with more severe positive symptoms tended to spend more time on the SOAR site (r=.65, p=.005) and to access SOAR more frequently (r=.62, p=.009). Cumulative Web site usage was weakly associated with magnitude of positive symptom reduction (based on within-subject reduction in positive symptoms from baseline to 12 months), but the relationship was not statistically significant. Supporters in the telehealth group showed a large improvement in knowledge about prognosis (t=2.32, df=14, p=.036, d=1.94). No significant effects were observed on other domains of schizophrenia-related knowledge.

Discussion

The findings are remarkable in terms of the high level of engagement in online activities of persons with schizophrenia (100%) and supportive persons in their lives (92%) and the substantial usage of telehealth resources. Positive symptoms and knowledge about schizophrenia improved. In addition, higher Web site usage was associated with higher rates of positive symptoms, suggesting that those most in need of treatment sought and used a greater "dose" of the telehealth intervention. Perhaps surprising was the relatively higher level of participation of persons with schizophrenia compared with their supporters, a finding that may reflect a generation-based discomfort with technology or caused by the support group's composition, a highly diverse yet relatively small group. More than one member of the group of support persons suggested that the group be larger or more homogeneous to allow members to more easily bond over common experiences. The sustained involvement with the SOAR site suggests that the intervention has the potential to be a viable approach to providing therapies such as family psychoeducation to clients and their support network.

Although family psychoeducation is commonly associated with reductions in relapse rates and intimately involved in controlling positive symptom exacerbations, only some psychoeducation programs have shown a reduction in positive symptoms ( 31 , 32 , 33 ), whereas many have not ( 34 ). SOAR's significant influence on positive symptoms is consistent with the intervention's goals and the details of its operation. An explanation may lie in the common topics for problem solving and discussion, which focused on managing positive symptoms, medications, and side effects, including talking to psychiatrists about these issues to minimize their interference with activities. Thus, although evaluation of possible mediating variables such as medication adherence, side effect management, and readiness to talk with the prescribing psychiatrist about these issues was beyond the scope of this study, it is possible that concerns about symptom-related problems were positively influenced by the forum discussions and answers from the Ask the Expert feature.

Web site usage is certainly an indicator of engagement and may be a sufficiently valid indicator for most users, but it likely falls short as a measure of ongoing engagement for all users. Exposure to treatment is paramount but also encompasses such qualities as valuing and being committed to treatment and participation in treatment activities, such as problem solving. Feedback from users indicated that a range of Web site usage may be observed even among those who believe in the effectiveness of the treatment and are engaged. Usage may be influenced by need, which can vary over time because of intervention success, degree of symptom control, medication difficulties, severity of stresses, changes in coping resources, and so on. It has also been noted that disengagement may be an indication of successful behavior change ( 35 ). From this perspective, persons with schizophrenia who are more functional, have better personal and social resources, and have fewer problems taxing their ability to cope may still be engaged and benefit from intermittent use rather than more frequent or continuous use (see examples in the online appendix).

Because psychiatric symptoms and the underlying cognitive deficits of schizophrenia can interfere with an individual's ability to engage in meaningful and appropriate face-to-face interaction, computer-based interaction offers significant advantages ( 36 , 37 ). The visual display of words on a monitor may help compensate for deficits in auditory processing, attention, and memory and may improve concentration and attention to the task. Moreover, interactions online versus in person may be less influenced by cognitive deficits and social impairments. Individuals who are highly sensitive to external stimulation or uncomfortable with direct interpersonal interaction can more actively manage interpersonal exposure by gauging and adjusting the intensity of their interactions. They can access the Web site in small "doses," even at odd hours when the resources of community clinics are not available. Finally, the experience of being able to personally and safely manage personal use of the Web site may generate a sense of empowerment and self-efficacy.

The telehealth model provides agencies and therapists with several advantages usually unavailable in community clinics: the ability to monitor patient participation and increase direct services as needed, provide groups that minimize professional impact and emphasize peer-driven interaction and problem solving, and provide proven informational and support services to supportive families and friends in a destigmatizing way.

Despite these apparent advantages, there are limitations to this study, including the relatively small sample. Although small, the sample was relatively heterogeneous with regard to demographic and clinical features. Given that the use of Web-based technologies can involve complex information processing and require flexible, time-sensitive sensory-motor and integrative cognitive functions ( 38 ), the cognitive deficits associated with serious mental illness must be taken into account in the design of these technologies. Because there was no earlier research on technology design for persons with serious mental illness, we initiated such research in preparation for this study, identifying features that influence Web site usage by this population. On the basis of these findings, we created an appropriate design for the SOAR Web site ( 12 ), which runs counter to current design guidelines for the general public. The unique interface design of SOAR was not only acceptable to users, but it was also likely to have been a contributing factor in their ability to access the site effectively.

Conclusions

Clearly there is a need for cost-effective ways of successfully delivering evidence-based programs to the community. Telehealth programs may offer an ideal solution. Experts based in central locations can provide a sophisticated intervention to underserved individuals and families living in widely dispersed areas, eliminating the need for individual agencies to have the necessary startup funds or clinical expertise. These findings suggest that when telehealth services are specifically designed to accommodate the cognitive deficits of persons with schizophrenia, the services can and will be used. Online delivery of psychotherapeutic treatment to consumers' homes can improve consumer well-being and offers several advantages over standard clinic-based delivery models.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This project was supported by grant R01 MH63484 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Eack receives consulting fees from Abbott Laboratories. Dr. Ganguli is a consultant for Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson, and Eli Lilly and Company, and he works under a research grant funded by Bristol Myers-Squibb. The other authors report no competing interests.

1. Institute of Medicine: Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2001Google Scholar

2. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM, Dixon LB, et al: Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) Client Survey. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:11–20, 1998Google Scholar

3. Anderson CM, Reiss DJ, Hogarty GE: Schizophrenia and the Family: A Practitioners Guide to Psychoeducation and Management. New York, Guilford, 1986Google Scholar

4. McFarlane W: Multifamily Groups in the Treatment of Severe Psychiatric Disorders. New York, Guilford, 2002Google Scholar

5. Mueser KT, Glynn SM: Behavioral Family Therapy for Psychiatric Disorders, 2nd ed. Oakland, Calif, New Harbinger, 1999Google Scholar

6. Falloon IR, Held T, Roncone R, et al: Optimal treatment strategies to enhance recovery from schizophrenia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 32:43–49, 1998Google Scholar

7. Mari JJ, Streiner DL: An overview of family interventions and relapse on schizophrenia: meta-analysis of research findings. Psychological Medicine 24:565–578, 1994Google Scholar

8. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: Translating research into practice: the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations, Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1–10, 1998Google Scholar

9. Schizophrenia Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Schizophrenia in Primary and Secondary Care (National Clinical Practice Guideline update). National Clinical Practice Guideline Number 82.9. London, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2009Google Scholar

10. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Pub no SMA-03-3832. Rockville, Md, Department of Health and Human Services, President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003Google Scholar

11. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 1999Google Scholar

12. Rotondi AJ, Sinkule J, Haas GL, et al: Designing Websites for persons with cognitive deficits: design and usability of a psychoeducational intervention for persons with severe mental illness. Psychological Services 4:202–224, 2007Google Scholar

13. Anderson CM, Hogarty GE, Reiss DJ: Family treatment of adult schizophrenic patients: a psycho-educational approach. Schizophrenia Bulletin 6:490–505, 1980Google Scholar

14. McFarlane WR, Link B, Dushay R, et al: Psychoeducational multiple family groups: four-year relapse outcome in schizophrenia. Family Process 34:127–144, 1995Google Scholar

15. McCubbin MA, McCubbin HI: Family Systems Assessment. New York, Wiley, 1996Google Scholar

16. Allen S, Mor V: The prevalence and consequences of unmet needs: contrasts between older and younger adults with disability. Medical Care 35:1132–1148, 1997Google Scholar

17. Bandura A: Self-efficacy; in Encyclopedia of Human Behavior. Edited by Ramachandran VS. New York, Academic Press, 1994Google Scholar

18. Onken S, Dumont J, Ridgway P, et al: Mental Health Recovery: What Helps and What Hinders? A National Research Project for the Development of Recovery-Facilitating System Performance Indicators. Alexandria, Va, National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, National Technical Assistance Center for State Mental Health Planning, 2002Google Scholar

19. Cohen S, Wills TA: Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin 98:310–357, 1985Google Scholar

20. Rotondi AJ, Haas GL, Anderson CM, et al: A clinical trial to test the feasibility of a telehealth psychoeducational intervention for persons with schizophrenia and their families: intervention and 3-month findings. Rehabilitation Psychology 50:325–336, 2005Google Scholar

21. McFarlane W, Deakins S, Gingerich SL, et al: Multiple-Family Psychoeducational Group Treatment Manual. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biosocial Treatment Division, 1991Google Scholar

22. Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1984Google Scholar

23. Barrowclough C, Tarrier N: Families of Schizophrenic Patients: Cognitive Behavioural Intervention. London, Chapman & Hall, 1992Google Scholar

24. Raudenbush DSW, Bryk DAS: Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 2002Google Scholar

25. Schafer JL, Graham JW: Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods 7:147–177, 2002Google Scholar

26. Joe GW, Simpson DD, Broome KM: Retention and patient engagement models for different treatment modalities in DATOS. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 57:113–125, 1999Google Scholar

27. Garnick DW, Lee MT, Chalk M, et al: Establishing the feasibility of performance measures for alcohol and other drugs. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 23:375–385, 2002Google Scholar

28. Ho AP, Tsuang JW, Liberman RP, et al: Achieving effective treatment of patients with chronic psychotic illness and comorbid substance dependence. American Journal of Psychiatry 56:1765–1770, 1999Google Scholar

29. Tyron GS, Winograd G: Goal consensus and collaboration; in Psychotherapy Relationships That Work. Edited by Norcross JC. New York, Oxford University Press, 2002Google Scholar

30. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, Rev ed. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 1988Google Scholar

31. Falloon IRH, Boyd JL, Williamson M, et al: Family management in the prevention of morbidity of schizophrenia: clinical outcome of a two-year longitudinal study. Archives of General Psychiatry 42:887–896, 1985Google Scholar

32. Falloon IRH, Boyd JL, McGill CW, et al: Family management in the prevention of exacerbations of schizophrenia: a controlled study. New England Journal of Medicine 306:1437–1440, 1982Google Scholar

33. Shin SK, Lukens EP: Effects of psychoeducation of Korean Americans with chronic mental illness. Psychiatric Services 53:1125–1131, 2002Google Scholar

34. Lincoln TM, Wilhelm K, Nestoriuc Y: Effectiveness of psychoeducation for relapse, symptoms, knowledge, adherence and functioning in psychotic disorders: a meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Research 96:232–245, 2007Google Scholar

35. Strecher V, McClure J, Alexander GE, et al: The role of engagement in a tailored Web-based smoking cessation program: randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research 10:e36, 2008Google Scholar

36. Madoff SA, Pristach CA, Smith CM, et al: Computerized medication instruction for psychiatric inpatients admitted for acute care. MD-Computing 13:427–441, 1996Google Scholar

37. Weber B, Fritze J, Schneider B, et al: Computerized self-assessment in psychiatric in-patients: acceptability, feasibility and influence of computer attitude. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 98:140–145, 1998Google Scholar

38. Stephanidis C: User Interfaces for All: Concepts, Methods and Tools. Mahwah, NJ, Erlbaum, 2000Google Scholar