A Relationship-Based Care Model for Jail Diversion

Concern regarding the prevalence of mental illness within the criminal justice system has generated a proliferation of mental health courts and treatment programs designed specifically for this population. The U.S. Department of Justice recently estimated that over half of inmates in prisons and jails have a mental health problem ( 1 ). Although some feel this is an overestimation ( 2 ), partly because of the manner in which mental illness was defined in this study, there is consensus that a significant percentage of inmates struggle with some mental disorder. Moreover, the appropriateness of incarceration, adequacy of treatment, and financial expenditures associated with their care has prompted interest in jail diversion programs.

These programs have been largely heralded as a success, and data are now being amassed that will allow for evaluation of different types of programs in order to identify elements that enhance effectiveness. Diversion programs are typically classified as either prebooking, in which individuals are diverted before arrest by trained law enforcement personnel, or postbooking, referring to jail- or court-based programs that strive to waive or reduce charges or time of incarceration as a condition of a mental health treatment disposition ( 3 ). The main objectives of these programs are to avoid or reduce incarceration for nonviolent individuals with mental illness, reduce criminal recidivism, and improve psychiatric stability via sustained contact with community-based treatment providers ( 4 ).

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has been promoting data collection and analysis geared at identifying best practices for persons with mental illness and contact with the criminal justice system. In 1997 SAMHSA launched a Knowledge and Development Application on jail diversion programs to facilitate research and translate findings into practical applications for program development. Both pre- and postbooking programs seem to be effective, particularly to the extent that they integrate mental health services, substance abuse treatment, and supportive services into a cohesive program ( 3 , 4 , 5 ). Efficient coordination between service providers and criminal justice agencies enhances outcome, as does early engagement, in which the first contact is made while the individual is incarcerated ( 6 ). A multisite, longitudinal study assessing effectiveness of diversion programs found that outcomes seem to be dependent on access to care and the type of treatment intervention received after diversion ( 3 ).

Homelessness seems to confer added burden to persons with mental illness within the criminal justice system ( 7 , 8 ). Several studies have reported increased psychiatric disability among homeless individuals who are incarcerated ( 9 , 10 , 11 ). One study followed over a four-year period 5,774 individuals with mental illness and a history of homelessness and incarceration and found that those with severe mental illness demonstrated increased lengths of incarceration and poorer levels of community adjustment ( 10 ). The homeless population also proves challenging in terms of engagement, an interpersonal construct appearing to correlate with favorable outcome ( 12 , 13 ). Engagement has been defined as the process of establishing rapport while providing basic needs (for example, food, shelter, and access to care) ( 12 ). Park and colleagues ( 13 ) noted that degree of engagement with others and perception of program staff (for example, seeing them as well-disposed or suspicious) have good predictive validity in terms of housing status and adequacy of support network. Elaborating on this premise, we hypothesized that a program based on a model of relationship establishment may prove useful with this population. Although there is mention in the literature regarding the importance of choice and perceived mastery when developing service delivery programs for the homeless ( 14 ), little research has appeared regarding models that specifically focus on the interpersonal elements critical for establishing positive relationships.

In this article we report on our experience of applying our relationship-based care model to a treatment-intensive diversion program. We examined arrest rates for a cohort of homeless individuals with mental illness during the one-year period before court diversion and compared those with arrest rates for the one-year period after diversion. Data on program adherence and placement into permanent housing for our treatment group were used to determine whether the outcome was favorable. We also assessed various demographic elements, homelessness status, and level of involvement in psychiatric treatment to determine possible correlations with postdiversion arrest rates and a favorable outcome.

Methods

The study involved retrospective analysis of data sets in which no identifying information was used in the analysis or reporting. Consequently, the institutional review board of Citrus Health Network (CHN) did not feel informed consent was necessary. We reviewed data for 229 individuals aged 18 years or older who were arrested in Miami-Dade County from January 2002 through November 2006 and found to be appropriate for jail diversion. Data for 151 individuals who were consecutively diverted to our treatment program were compared with data for a control group of 78 individuals who had been diverted to other programs in which supportive housing in assisted living facilities and psychiatric treatment as usual in community mental health centers were provided. All individuals were deemed indigent and homeless. With the intent of maximizing compliance to programs, referrals by the court to a specific diversion program were made largely on the basis of geographic location of the program and the preference of the diverted individual.

Program description and data

CHN is a Federally Qualified Health Center located in a predominantly Hispanic area of Miami-Dade County, Florida. CHN specializes in the integration of primary care and mental health services and has significant experience in meeting the needs of individuals with severe mental illness. In 2000 CHN received funding to develop its jail diversion program, in keeping with a countywide initiative prompted by Judge Steve Leifman, Associate Administrative Judge of the Eleventh Judicial Circuit in Miami-Dade County.

Our clinical and administrative team at CHN formulated an approach predicated on facilitating the interaction between general medical and psychiatric care in order to enhance psychosocial stability and reduce criminal recidivism. We began by training a specialized outreach team whose primary objective is engagement. Upon receiving a referral, the team quickly initiates contact to begin establishing a relationship, conducts a PATH (Projects for Assistance in Transition From Homelessness) assessment ( 15 ) to determine immediate needs, and serves as an advocate at time of hearing. When the client is released from jail, the team arranges for transportation to CHN for a full medical and psychiatric assessment and then arranges placement in transitional housing. Throughout the program, case management, health education groups, and other supportive services are provided to encourage active interest and participation in managing psychiatric and general medical problems. The program is also designed to assist individuals in obtaining permanent independent housing, an outcome that we feel correlates with clinical and psychosocial stability.

Relationship-based care

Our experience in treating individuals with pronounced difficulty in engagement and sustained interpersonal contact led us to develop our relationship-based care model, which serves as the conceptual platform undergirding our program. In addition to using specific intervention techniques, the relationship-based care model uses a philosophical approach pervading all interactions with participants. The model assumes that the empathy, respect, and connectedness inherent in healthy relationships can be instrumental in engaging individuals in therapeutic activities and empowering them to take responsibility for their lives.

Relationship-based care incorporates elements from other philosophically compatible approaches. In addition to building upon the sense of acceptance inherent in a low-demand model, the approach embraces several principles espoused in motivational enhancement therapy ( 16 ). The principle of "express empathy" directs us to communicate respect and encourage collaboration with staff members, who come to be viewed as a blend of supportive companions and knowledgeable consultants. The concept of "rolling with resistance" is also in keeping with the low-demand model; although staff members do not directly confront the client's resistance to treatment, they try to facilitate helping the client see a discrepancy between his or her perception of the current situation and future aspirations. Consistent with motivational enhancement therapy, an end-point objective of relationship-based care is establishing self-efficacy and self-agency, in which individuals develop a sense that they can change specific behaviors, act on their own behalf, and take responsibility and accountability for their decisions.

In addition to training staff in motivational enhancement therapy, we conceptualized the following stages that serve to operationalize relationship-based care and facilitate implementation: engagement, stability and commitment, awakening, and growth and differentiation. During engagement, the initial foundation of a relationship is established; motivational interviewing techniques are used to mobilize self-interest and encourage the individual to choose care. Stability and commitment marks a period of rest and quiescence in which participants begin to feel safe and secure. This stage consolidates the relationship with staff, as evidenced by an individual's accepting physical and mental health care, developing trust to rely on others for basic needs, and collaborating with others to obtain day-to-day stability. We note that although some clients did not progress past this phase, they were nonetheless able to successfully remain out of jail. Probability for long-term change, however, increases if an individual progresses through the next stages. The third stage, awakening, refers to a phenomenon we have observed in which individuals begin manifesting a desire for more than the day-to-day existence of meeting basic needs. Some have enjoyed a higher level of premorbid functioning and wish to return to that level; others are limited in their psychosocial development but begin striving for more. This stage is marked by an individual's taking increased advantage of the therapeutic, educational, and rehabilitation opportunities offered to them through our program. We have labeled the final stage growth and differentiation, in which participants maintain stability, demonstrate new adaptive behaviors, exhibit signs of psychosocial flourishing, and ultimately transition into independent living. [An appendix showing more details about the four stages of relationship-based care is available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline.org .]

Arrest rates

Arrest rates were obtained from the Criminal Justice Information System in Miami-Dade County. Number of arrests for each participant was determined for the one-year period before the date of diversion, followed by a review of arrests during the one-year period after diversion.

Characteristics of the relationship-based care group

In order to better understand variables that may have an impact on outcome, we collected data for the relationship-based care treatment group; similar data were unavailable for the control group. We categorized homeless status according to the Housing and Urban Development definition: chronic (being continuously homeless for more than one year or four or more episodes of homelessness during a three-year period) or situational (homeless for less than a year or less than four episodes of homelessness over three years) ( 17 ). We also recorded the clinical diagnosis for each participant in the relationship-based care group, as well as number of outpatient psychiatric visits for each individual while he or she participated in the program. We also examined the overall time spent in the program. Outcome at the end of the study was categorized as either unfavorable (defined by postdiversion arrest or premature departure before program goals were met) or favorable (either still active in the program or successfully placed in permanent housing).

Results

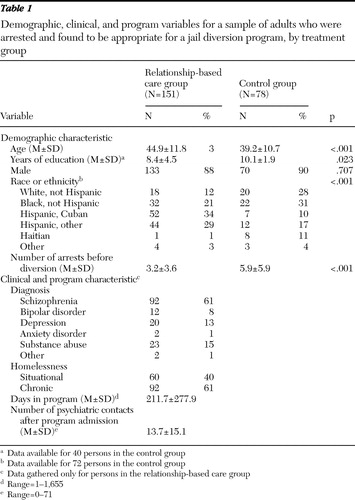

Demographic data for the relationship-based care treatment group and the control group are summarized in Table 1 . The entire sample was composed of mainly young to middle-aged adult males, and persons in the control group were significantly younger than those in the relationship-based care group. There was no difference in gender distribution between groups. Both groups averaged less than a high school education, although the grade level was significantly higher for the control group. Education level did not correlate with other demographic, clinical, or outcome variables. Significant racial and ethnic differences were present between groups, with more Hispanics in the relationship-based care treatment group (63%) than in the control group (27%). This reflects the court-based diversion process, in which Hispanics opted for our program because of its location in a predominantly Hispanic area of Miami-Dade County. Arrest rates in the year before diversion were significantly higher for the control group.

|

For the relationship-based care treatment group, 61% of the sample were chronically homeless. A significant majority of participants had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and the most frequent second and third diagnoses were substance abuse and depression, respectively. Nonparametric analysis did not reveal a relationship between diagnosis and nature of homelessness or outcome. Additionally, diagnosis was unrelated to number of arrests before or after admission into the program, number of psychiatric contacts, or length of participation in the program.

Duration of participation in the relationship-based care program ranged between one and 1,655 days, with a group average of 212 days. There was a significant inverse correlation between length of time in the program and number of arrests before admission (p=.007) and a more robust inverse correlation with the number of arrests after program admission (p<.001). Number of psychiatric contacts after admission ranged from 0 to 71, with a group average of 14 contacts. There was a significant correlation between number of psychiatric contacts and having a favorable outcome at study end (p<.001). Age, gender, and education were not related to overall duration in the program. Forty-two (28%) participants left the program within the first 30 days, which we feel represents a critical period for engagement.

Postdiversion arrest rates

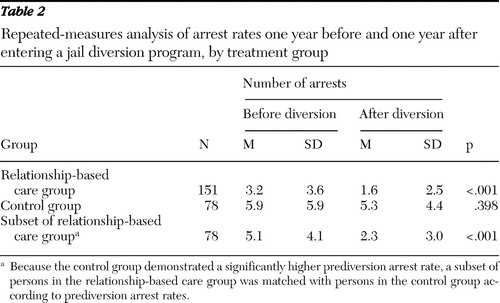

Table 2 summarizes pre- and postdiversion arrest rates. These data indicate a significant reduction in arrest rates for the relationship-based care group (p<.001), whereas the arrest rate for the control group remained nearly identical before and after diversion. For both groups, postdiversion arrest rates were significantly correlated with the number of arrests before diversion (p<.001). Because the control group demonstrated a significantly higher prediversion arrest rate, a subset of persons in the relationship-based care group matched with persons in the control group according to prediversion arrest rates was used to address this potentially confounding factor. Comparisons using t tests revealed no difference between the control group and the arrest-matched subgroup in prediversion arrest rates. After diversion, however, the relationship-based care subgroup demonstrated a significant decrease in arrest rates (p<.001).

|

For the entire relationship-based care group, regression analysis revealed that when number of prior arrests was excluded from the equation, the length of participation in the program (p<.045) and the number of psychiatric contacts (p<.043) accounted for a significant portion of the variance in postdiversion arrest rates. Although chronic homelessness was associated with a greater number of arrests during the year before diversion (p=.04), there was no difference in postdiversion arrest rates between chronic and situational homelessness after admission.

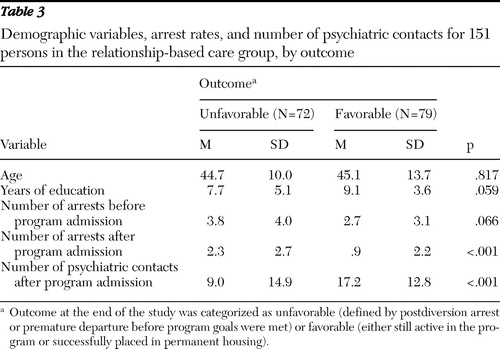

Outcomes for the relationship-based care group

We next categorized relationship-based care participants according to whether they had a favorable or unfavorable outcome at study end ( Table 3 ). The groups did not differ on any demographic or clinical variables. Although no difference was noted in number of prediversion arrest rates, there were significantly fewer postdiversion arrests for individuals who remained in the program or attained permanent housing (favorable outcome) (p<.001). As expected, individuals with a favorable outcome had a significantly higher number of psychiatric contacts, compared with those with an unfavorable outcome (p<.001).

|

Of the 72 individuals in the group with an unfavorable outcome, 42 (58%) had left within the first 30 days (28% of the total sample). We isolated this group and ran a comparison to determine whether any demographic or clinical variables had an impact on program adherence. Lower educational attainment was the sole variable significantly correlated with departure within 30 days. The two groups did not differ in terms of number of arrests before admission. As expected, leaving the program within the first 30 days was associated with increased frequency of postdiversion arrests (p<.001).

Discussion

Results indicated a highly significant reduction in arrest rates after admission to our program, a finding that we feel supports the effectiveness of this type of diversion program. Our program prioritizes access to psychiatric and primary health care, using a directive and relationship-based approach. Individuals are encouraged to develop relationships not only with staff and each other but also with the CHN system as their service provider. Our sense is that this philosophical approach transcends singular relationships and empowers individuals to feel comfortable accessing treatment from our organization.

For our particular sample, we were unable to isolate any clinical or demographic variables—aside from number of arrests before admission—that identified those at risk of criminal recidivism. The longer individuals remained in our program, the less likely they were to be arrested. Similarly, compliance with psychiatric treatment, as measured by number of outpatient contacts, was also correlated with decreased postdiversion arrest rates. Although these findings may be interpreted as reflecting the beneficial aspects of psychiatric intervention or broader elements of our program, it is also possible that this portion of the sample consisted of healthier individuals who were able to take advantage of the program and were inherently at reduced risk of recidivism.

Feedback from our frontline staff and clients indicates that, aside from the respect and sense of hope promoted within the program, the emphasis on immediate assessment of general medical and psychiatric status is critical. Centers that are able to provide access to both psychiatric and primary care services are at an advantage, although admittedly we are aware that many community mental health centers face barriers in obtaining general medical care for their patient population ( 18 ). Nonetheless, diversion programs that can arrange for both services may be more effective in engaging a population that is high in resistance to treatment and low in utilization of services ( 12 ). It is interesting that even some of the individuals who left our program prematurely continued to access CHN's general medical and psychiatric services for ongoing care.

Our findings corroborate what is known about the challenges of engagement. As noted, among those who left the program prematurely, almost 60% did so within the first 30 days. Rapidly identifying those at risk of premature departure—and consequently at risk of postdiversion arrest—may facilitate the development of differential intervention strategies to improve program adherence. In our sample, lower education was the only demographic element statistically correlated with departure within 30 days. However, number of arrests before diversion and more severe homelessness (represented by the chronic designation) seem to be risk factors for a poorer outcome.

We are currently reviewing strategies to increase program retention. There has been some consideration of inserting a decision-making step early in the referral process geared at identifying high-risk individuals, who would then undergo a "guesting" period of three to five days on our inpatient unit before placement in transitional housing. The rationale would be to determine whether or not the increased intensity of initial assessment and therapeutic intervention would have a positive impact on engagement. As has been suggested ( 13 ), use of a formal measure that could objectively quantify help-seeking status or likelihood of engagement may prove beneficial for identifying individuals at risk of premature departure.

Conclusions

In keeping with the SAMHSA initiative, this study adds to the growing body of literature regarding outcomes of diversion programs. We are encouraged by the significant reduction in arrest rates that our program was able to achieve and feel that it supports the effectiveness of a treatment-intensive and relationship-based diversion program.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors thank Cindy A. Schwartz, M.S., M.B.A., and Tim Coffey, M.S., of the Eleventh Judicial Circuit Criminal Mental Health Project for their cooperation in the data collection process, as well as Judge Steve Leifman for his dedication and passionate advocacy for those with mental illness.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. James DJ, Glaze LE: Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report: Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates. Pub no NCJ 213600. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, 2006Google Scholar

2. Kuehn BM: Mental health courts show promise. JAMA 297:1641–1643, 2007Google Scholar

3. Steadman HJ, Morris S, Dennis DL: The diversion of mentally ill persons from jail to community-based services: a profile of programs. American Journal of Public Health 85:1630–1635, 1995Google Scholar

4. Steadman HJ, Deane MW, Morrissey JP, et al: A SAMHSA research initiative assessing the effectiveness of jail diversion programs for mentally ill persons. Psychiatric Services 50:1620–1623, 1999Google Scholar

5. Subcommittee on Criminal Justice: Background Paper. DHHS pub no SMA-04-3880. Rockville, Md, New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2004Google Scholar

6. Loveland D, Boyle M: Intensive case management as a jail diversion program for people with a serious mental illness. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 51:130–150, 2007Google Scholar

7. McNiel DE, Binder RL, Robinson JC: Incarceration associated with homelessness, mental disorder, and co-occurring substance abuse. Psychiatric Services 56:840–846, 2005Google Scholar

8. Greenberg GA, Rosenheck RA: Jail incarceration, homelessness, and mental health: a national study. Psychiatric Services 59:170–177, 2008Google Scholar

9. Delisi M: Who is more dangerous? Comparing the criminality of adult homeless and domiciled jail inmates: a research note. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 44:59–69, 2000Google Scholar

10. McGuire JF, Rosenheck RA: Criminal history as a prognostic indicator in the treatment of homeless people with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 55:42–48, 2004Google Scholar

11. White MC, Chafetz L, Collins-Bride G: History of arrest, incarceration and victimization in community-based severely mentally ill. Journal of Community Health 31:123–135, 2006Google Scholar

12. Mowbray CT, Cohen E, Bybee D: The challenge of outcome evaluation in homeless services: engagement as an intermediate outcome measure. Evaluation and Program Planning, 16:337–346, 1993Google Scholar

13. Park MJ, Tyrer P, Elsworth E, et al: The measurement of engagement in the homeless mentally ill: the Homeless Engagement and Acceptance Scale—HEAS. Psychological Medicine 32:855–861, 2002Google Scholar

14. Greenwood RM, Schaefer-McDaniel NJ, Winkel G, et al: Decreasing psychiatric symptoms by increasing choice in services for adults with histories of homelessness. American Journal of Community Psychology 36:223–238, 2005Google Scholar

15. Projects for Assistance in Transition From Homelessness. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2008. Available at www.pathprogram.samhsa.gov Google Scholar

16. Miller WR, Rollnick S: Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior. New York, Guilford, 1991Google Scholar

17. Notice of funding availability for the collaborative initiative to help end chronic homelessness. Federal Register 68:4019, Jan 27, 2003Google Scholar

18. Druss BG, Marcus SC, Campbell J, et al: Medical services for clients in community mental health centers: results from a national survey. Psychiatric Services 59:917–920, 2008Google Scholar