Influence of Family Involvement and Substance Use on Sustained Utilization of Services for Schizophrenia

Irregular patterns of service use, including attrition from care, are common among individuals with schizophrenia, as they are among individuals with other chronic conditions ( 1 , 2 ). Both the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study and the National Comorbidity Survey found that approximately half of individuals with schizophrenia had received no mental health services in the preceding 12 months ( 3 , 4 ). Among those who received outpatient care for schizophrenia, some 25%–30% dropped out of care within a 12-month period ( 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ). Irregular service use is associated with less favorable outcomes of care for schizophrenia, including greater symptom severity and rehospitalization ( 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ). These outcomes are extremely expensive in both human and financial terms.

Identification of personal characteristics associated with irregular service use may help providers predict which consumers are likely to sustain involvement in care. However, if we are to improve rates of sustained involvement in care, we need to emphasize identification of the modifiable characteristics associated with patterns of utilization. We recently conducted in-depth qualitative interviews with individuals with schizophrenia to elicit their perspectives on crucial barriers to and facilitators of sustained involvement in care. Participants reported that support from family members and friends was a crucial contributor to sustained involvement, especially in rural areas where family and friends often helped with transportation. They also reported that substance use or abuse was a common barrier to remaining in care over time. For the study presented here, we analyzed service utilization data to determine whether and how much these two modifiable factors (family support and substance abuse) influenced patterns of care for schizophrenia.

Methods

Sample

Data for these analyses were collected between 1992 and 1999 as part of two longitudinal, observational studies designed to validate and assess the psychometric properties of the Schizophrenia Outcomes Module, a comprehensive measure of symptom status and quality of life in schizophrenia ( 15 , 16 ). In both studies, trained research assistants interviewed consumers and consumer-designated "informants" (family members, friends, or providers who knew the consumer well) and abstracted mental health service utilization data from consumers' medical records. All consumer participants met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia and were Arkansas residents between the ages of 18 and 67 years at enrollment (N=319). Approximately half were recruited at discharge from a short-term inpatient admission to either the Arkansas State Hospital or the Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System (CAVHS) Medical Center. All others were recruited from CAVHS or nonfederal public-sector outpatient mental health clinics in Central Arkansas. For this report, we analyzed demographic, clinical, social, and utilization data for the 258 consumer participants for whom we had mental health services utilization information covering a period of at least 18 consecutive months (81% of total sample). In the case of consumer participants for whom we had 18 months of utilization data from both of the previous studies, we used only data from the more recent study.

Participation rates for the original two studies were 82%–84% at baseline and 91%–92% at follow-up. At baseline, participants were somewhat more likely than nonparticipants to be male, white, and not currently married and to have a history of substance abuse. They did not differ in age or residence (urban or rural areas). As a result of recruitment from predominantly male VA settings and the higher rate of nonparticipation among women, women were underrepresented in the sample. At follow-up, nonparticipants differed significantly from participants only with regard to nonparticipants' higher rate of current substance abuse at baseline. (Data available from the first author upon request.) Because nonparticipants were a small proportion of potential participants, the combined study sample, aside from gender, was generally representative of Arkansans receiving services for schizophrenia in public-sector mental health facilities in the 1990s.

Both the original studies and the study presented here were approved by the joint University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences and Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System Institutional Review Board. All participants provided written informed consent following full discussion of study procedures.

Outcome variable: pattern of service use

We created a trichotomous summary outcome variable that categorized mental health service use patterns as regular, irregular, or infrequent. We defined regular service use as outpatient mental health care contact an average of at least once every three months with no breaks in contact lasting more than four consecutive months, irregular service use as outpatient mental health care contact an average of at least once every three months with one or more breaks in contact lasting more than four consecutive months, and infrequent service use as contact with outpatient mental health care an average of less than once every three months. We used the detailed information on each consumer's contacts with mental health care providers during the study period to assign the consumer to the appropriate outcome category. Inpatient time was excluded from calculations of frequency of contact and breaks in contact.

Predictor variables

The predictor variables of interest were three predisposing factors and enabling/reinforcing factors ( 17 , 18 , 19 ) identified through qualitative interviews with consumers as critical to their ongoing involvement in care: consumer substance abuse status, family support, and residence (rural or urban area). Clinically trained research assistants administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R ( 20 ) or DSM-IV ( 21 ) (SCID) to consumers to assess their current substance abuse status as well as to confirm the diagnosis of schizophrenia. Substance abuse was defined as meeting SCID criteria for abuse of or dependence on alcohol or drugs, excluding nicotine, in the 30 days before the interview for outpatient recruits or in the 30 days before hospital admission for inpatient recruits. Family support was dichotomized, with consumers being categorized as "known to have at least weekly family support" or "not known to have at least weekly family support." Consumers were classified as receiving weekly family support if a family member (that is, parent, spouse or significant other, sibling, child, or other relative) reported providing transportation, helping with shopping, preparing meals, helping with household chores, offering advice, reminding to take medications, or managing money an average of once a week or more. We used the Office of Management and Budget's definition of rurality to classify consumers as urban residents (living in counties that are metropolitan statistical areas) or rural residents (not living in metropolitan statistical areas) ( 22 ). Potential confounding variables included in analyses were recognized clinical and demographic predisposing factors: insight into illness, cognitive functioning, age, gender, and ethnicity.

We used consumers' average scores on the Awareness of Illness questionnaire, an eight-item semistructured interview instrument, as our measure of insight. Possible average scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating less insight ( 23 ). We used consumers' total score on the attention, judgment, memory, and similarities subscales of the Neurobehavioral Cognitive Status Examination as our measure of cognitive functioning. Possible scores range from 0 to 34, with higher scores indicating better cognitive function ( 24 ).

Statistics

In bivariate comparisons among utilization categories, we used chi square tests for categorical variables and analysis of variance with Duncan tests for post hoc between-group differences for continuous variables. We used polychotomous logistic regression analysis for multivariable analyses ( 25 , 26 ). All analyses were performed with SAS software, version 8.02 for Windows.

Results

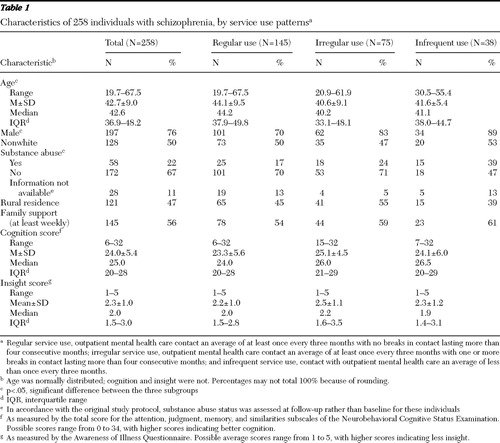

Sample characteristics are summarized in Table 1 , overall and by service use pattern. The overall sample was predominantly male (76%), middle-aged, and approximately evenly divided by ethnicity (130 sample members, or 50% were white, and 128 sample members, or 50%, were nonwhite). Consistent with the population of Central Arkansas in the 1990s, all but two of the nonwhite sample members were African American (N=126, or 49%); one of the remaining two individuals was Hispanic, the other was from "other" race or ethnicity. Substantial proportions of sample members met criteria for a current substance use disorder (22%), were rural residents (47%), and were known to have had at least weekly family support (56%). A majority of sample members used mental health services regularly (145 consumers, or 56%). The three subgroups defined by pattern of service use differed significantly in current substance abuse status ( χ2 =12.19, df=4, p=.016), age (F=4.18, df=2 and 255 p=.016), and gender ( χ2 =8.88, df=2, p=.012). Regular service users were more likely to be female and were slightly older than irregular or infrequent service users. Substance abuse was least prevalent among regular service users and most prevalent among infrequent service users. The subgroups did not differ significantly in ethnicity, residence, family support, cognitive functioning, or insight.

|

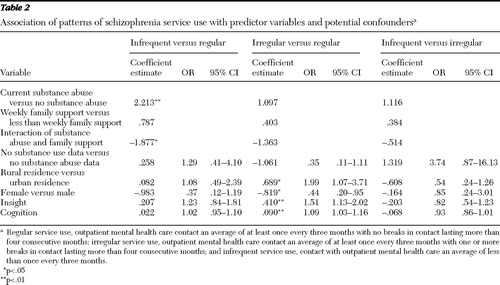

We used polychotomous logistic regression to first regress pattern of service use on the predictor variables of interest (substance abuse status, family support, and rural residence), adjusting for clinical predisposing factors (insight and cognitive functioning). Substance abuse status, cognitive functioning, and insight were significantly associated with the pattern of service use (p<.05). Guided by qualitative interview findings, we then assessed the influence of potential interactions between substance abuse status and family support and between substance abuse status and residence, separately and together. The interaction term for substance abuse status and family support was the only one that was statistically significant and substantially improved the model fit ( 26 ). Finally, we added standard demographic predisposing factors, age, gender, and ethnicity (white or nonwhite), to the model to assess their potential confounding effects. Gender was significantly associated with utilization pattern and added to model fit. Ethnicity and age did not contribute to model fit and were not included in the final regression model.

The final model was significant overall (likelihood ratio χ2 =43.06, df=16, p=.003). The interaction between substance abuse status and family support approached significance in the overall model (Wald χ2 =5.93, df=2, p=.052) and was statistically significant in the comparison between individuals with infrequent versus regular patterns of service use (Wald χ2 =4.86, df=1, p=.027). As shown in Table 2 , consumers with a pattern of infrequent outpatient contact were also more likely than those with a pattern of regular contact to meet criteria for current substance abuse (Wald χ2 =10.06, df=1, p=.002), even after adjustment for the interaction of substance abuse status and family support. Consumers with a pattern of irregular outpatient contact were significantly more likely than those with a regular pattern of contact to be rural residents (Wald χ2 =4.73, df=1, p=.030), to be male (Wald χ2 =4.38, df=1, p=.036), and to have better cognitive functioning (Wald χ2 =8.28, df=1, p=.004) but poorer insight (Wald χ2 =7.64, df=1, p=.006). The interaction between substance abuse status and family support approached significance for this comparison (p=.073). None of the differences between consumers with patterns of irregular or infrequent service use reached statistical significance.

|

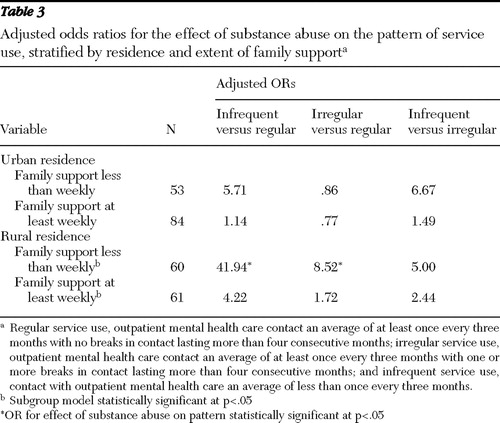

The statistical information in Table 2 cannot provide a clear picture of the direction or consistency of the substance abuse-family support interaction effect. To be able to describe the ways in which family support modified the effect of substance abuse status on pattern of service use and to determine whether the effect varied by residence, as suggested in our qualitative interviews, we repeated the logistic regression analysis stratified by support and residence. Odds ratios for the association of substance abuse status with utilization pattern, stratified by family support and rural or urban residence, are shown in Table 3 . Consistent with the results of the full-sample analysis, after adjustment for gender, cognitive functioning, and insight, substance abuse generally increased the likelihood of one of the less desirable patterns of care, regardless of residence or family support. However, the magnitude of the impact of substance abuse on utilization patterns was substantially lower among individuals known to have at least weekly family support, especially in rural areas. Because each of the analytic subgroups includes about a quarter (N=53–84) of the full sample, these exploratory subgroup analyses have considerably less power than the full-group analysis. With the smaller sample sizes, only the subgroup models for rural residents achieved statistical significance. Nonetheless, we consider it useful to show the results of these exploratory subgroup analyses because they most clearly illustrate the way family support and residence modify the association between substance abuse status and patterns of service use.

|

Discussion

In our sample of 258 individuals with schizophrenia, after adjustment for insight, cognitive functioning, and gender, comorbid substance abuse and the interaction between substance abuse and family support were significantly associated with patterns of service use. Comorbid substance abuse predicted less desirable utilization patterns. Inspection of stratified analyses indicated that weekly family support substantially reduced the adverse impact of substance abuse on consumers' patterns of service use, especially for consumers living in rural areas.

These findings reinforce the picture painted in the qualitative interviews we conducted previously with a small subsample of study participants. They are also generally consistent with the relatively small body of literature on patterns of care for individuals with schizophrenia and the much larger body of literature on predictors of antipsychotic medication adherence in this population. Comorbid substance abuse is a robust predictor of treatment attrition and medication nonadherence ( 2 ). Family support and involvement have also been associated with more sustained involvement in care and medication adherence ( 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ). To our knowledge, however, our finding that family support can offset some of the negative impact of substance abuse on sustained involvement in care has not been reported previously.

The study presented here has limitations. First, the relatively small sample size, especially for the group of infrequent service users, limited the power of multivariable models. Second, neither choosing to have a family member participate in the study nor being in contact with family was a criterion for consumer eligibility in either of the original studies. As a result, our measure of family support was based on information from family members who participated in the study. Consumers for whom we do not have data on family support were classified as "not known to have at least weekly family support." Some of those individuals may have had family support that we did not capture. Further, we did not ask about every possible type of family support. Individuals receiving other types of support only may also be misclassified. However, such misclassification would be expected to artificially decrease the magnitude of differences between groups rather than to exaggerate it. Third, because there is no consensus on the optimal frequency with which individuals with schizophrenia should be in contact with mental health service providers, any categorization of utilization patterns is inevitably arbitrary and open to debate. We selected a relatively lenient definition of "regular use" that reflected the least stringent visit interval commonly applied in our outpatient recruitment settings at the time of the study.

Our secondary data analyses cannot further elucidate the ways in which family support may at least partially offset the influence of substance abuse on service use patterns, nor can they identify the individuals for whom it does so. Data from the qualitative interviews that sparked these analyses suggest some mechanisms. Respondents with schizophrenia reported that family members provided transportation, reminded them of appointments, took them to care when they experienced an exacerbation of symptoms, and provided moral support and a feeling of worth. In their own words: "My nephew always reminds me [to keep my appointments] …. [I] ride the bus or my nephew takes me." "My oldest sister has power of attorney…. and Mother is my payee to make sure I get my Social Security." "My mother tells me I should stay in there [treatment] because it's good for me. My daughter tells me too." "Some of the things that helped [me stay in care] … family support, my wife and all, and my mother and brothers and sisters, family support. They supported me." "They [family] encourage me [to stay in treatment]." "Well, by having family … they give me a crutch, you know."

Further, in a longitudinal study of individuals with dual diagnoses of substance abuse and a mental disorder—primarily schizophrenia (54%) or schizoaffective disorder (23%)—Clark ( 31 ) found that direct family support (economic or instrumental) was associated with greater reductions in substance use over time. Importantly, those analyses, which adjusted for baseline consumer involvement in substance abuse treatment, provide strong suggestive evidence that family support is not solely determined by whether the consumer is in treatment for substance abuse or how well the consumer is doing in that treatment ( 31 ).

In many instances, the extent and nature of family support is a modifiable phenomenon. If the interaction we observed between family support and substance abuse is confirmed in other populations, it has potentially important implications. Comorbid substance abuse is prevalent among individuals with schizophrenia. At the same time, a high proportion of these individuals remain in touch with their families, and many live with family members ( 32 , 33 ). Dixon and colleagues ( 33 ) found that inpatients with dual diagnoses of severe mental illness and substance abuse reported a greater desire for family treatment than did inpatients diagnosed as having severe mental illness alone. In this context, our findings provide strong backing for efforts to increase the involvement of family members who provide informal care in the treatment process as well as to increase the support available to them. These efforts are crucial as the field increasingly transforms the "mental health treatment process" into a strengths-based "recovery process" ( 34 , 35 , 36 ) and are especially crucial for individuals with dual diagnoses who live in rural areas. The availability of evidence-based professional and lay programs for families as well as support groups for family members should facilitate increasing or reinforcing family involvement.

Although this is an intuitively appealing conclusion, its implementation faces significant challenges. Despite the empirical evidence of the importance of families in care of individuals with schizophrenia ( 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 ), few families have contact with the mental health care treatment team ( 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 ). The old ideas that contact with family impedes progress or is legally prohibited endure among clinicians ( 45 ). In addition, few facilities offer services for families, and those that do often find it difficult to engage family members of persons with schizophrenia ( 40 ). This may reflect, in part, families' struggle to handle the day-to-day burden of caregiving and instrumental support for their relative with schizophrenia. Additional information is needed on the mechanisms by which family support ameliorates the adverse impact of substance abuse on patterns of service use and, perhaps, on other aspects of consumers' lives. In addition, creative strategies will be needed, especially for rural areas, to address challenges to increasing the engagement of families in treatment to the level desired by their affected relative.

Conclusions

This study provides evidence that ongoing family support is associated with substantial reductions in the adverse impact of substance abuse on consumers' patterns of service use, especially for consumers living in rural areas. It suggests that reinforcing services and support for family members who provide informal care may help increase sustained involvement in care by the especially vulnerable population of individuals with dual diagnoses of schizophrenia and substance abuse.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by grant IIR01-116 from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Services Research and Development Service. Collection of utilization data was supported by grants SDR91-005, IIR94-109, and IIR98-094 from the VA Health Services Research and Development Service and grants RO3-MH-49123 and RO1-MH-055170 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Bruce ML, et al: The prevalence and correlates of untreated serious mental illness. Health Services Research 36:987–1007, 2001Google Scholar

2. Nosé M, Barbui C, Tansella M: How often do patients with psychosis fail to adhere to treatment programs? A systematic review. Psychological Medicine 33:1149–1160, 2003Google Scholar

3. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, et al: The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:85–94, 1993Google Scholar

4. Kessler RC, Zhao S, Katz SJ, et al: Past-year use of outpatient services for psychiatric problems in the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:115–123, 1999Google Scholar

5. Young AS, Grusky O, Jordan D, et al: Routine outcome monitoring in a public mental health system: the impact of patients who leave care. Psychiatric Services 51:85–91, 2000Google Scholar

6. Lehman AF, Dixon LB, Kernan E, et al: A randomized trial of assertive community treatment for homeless persons with severe mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:1038–1043, 1997Google Scholar

7. Mueser KT, Bond GR, Drake RE, et al: Models of community care for severe mental illness: a review of research on case management. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:37–74, 1998Google Scholar

8. Roth D, Snapp MB, Lauber BG, et al: Consumer turnover in service utilization patterns: implications for capitated payment. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 25:241–255, 1998Google Scholar

9. Sparr LF, Moffitt MC, Ward MF: Missed psychiatric appointments: who returns and who stays away. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:801–805, 1993Google Scholar

10. Weiden PJ, Olfson M: Cost of relapse in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:419–429, 1995Google Scholar

11. Fischer EP, Owen RR, Cuffel BJ: Substance abuse, community service use, and symptom severity of urban and rural residents with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 47:980–984, 1996Google Scholar

12. Killaspy H, Banerjee S, King M, et al: Prospective controlled study of psychiatric out-patient non-attendance: characteristics and outcome. British Journal of Psychiatry 176:160–165, 2000Google Scholar

13. Adair CE, McDougall GM, Mitton CR, et al: Continuity of care and health outcomes among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 56:1061–1069, 2005Google Scholar

14. Crawford MJ, de Jonge E, Freeman GK, et al: Providing continuity of care for people with severe mental illness: a narrative review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 39:265–272, 2004Google Scholar

15. Cuffel BJ, Fischer EP, Owen RR Jr, et al: An instrument for measurement of outcomes of care for schizophrenia: issues in development and implementation. Evaluation and the Health Professions 20:96–108, 1997Google Scholar

16. Fischer EP, Cuffel BJ, Owen RR, et al: Schizophrenia Outcomes Module (SCHIZOM), in Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000Google Scholar

17. Green LW, Kreuter MW: CDC's planned approach to community health as an application of PRECEDE and an inspiration for PROCEED. Journal of Health Education 23:140–147, 1992Google Scholar

18. Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD: The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Services Research 34:1273–1302, 2000Google Scholar

19. Pescosolido BA: Illness careers and network ties: a conceptual model of utilization and compliance. Advances in Medical Sociology 2:161–184, 1991Google Scholar

20. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW: User's Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

21. First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al: User's Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV AXIS I Disorders. New York, Biometrics Research, 1996Google Scholar

22. Hewitt M: Defining "Rural" Areas: Impact on Health Care Policy and Research. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1989Google Scholar

23. Cuffel BJ, Alford J, Fischer EP, et al: Awareness of illness in schizophrenia and outpatient treatment adherence. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 184:653–659, 1996Google Scholar

24. Manual for the Neurobehavioral Cognitive Status Examination. Fairfax, Calif, Northern California Neurobehavioral Group, 1991Google Scholar

25. Diggle PJ, Liang KY, Zeger SL: Analysis of Longitudinal Data. New York, Oxford University Press, 1998Google Scholar

26. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S: Applied Logistic Regression Analysis, 2nd ed. New York, Wiley, 2000Google Scholar

27. Olfson M, Mechanic D, Hansell S, et al: Predicting medication noncompliance after hospital discharge among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 51:216–222, 2000Google Scholar

28. Parashos IA, Konstantinos X, Zoumbou V, et al: The problem of non-compliance in schizophrenia: opinions of patients and their relatives: a pilot study. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice 4:147–150, 2000Google Scholar

29. Pescosolido BA, Wright ER, Alegría M, et al: Social networks and patterns of use among the poor with mental health problems in Puerto Rico. Medical Care 36:1057–1072, 1998Google Scholar

30. Pilling S, Bebbington P, Kuipers E, et al: Psychological treatments in schizophrenia: I. meta-analysis of family intervention and cognitive behaviour therapy. Psychological Medicine 32:763–782, 2002Google Scholar

31. Clark RE: Family support and substance use outcomes for persons with mental illness and substance use disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27:93–101, 2001Google Scholar

32. Brekke JS, Mathiesen SG: Effects of parental involvement on the functioning of noninstitutionalized adults with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 46:1149–1155, 1995Google Scholar

33. Dixon L, McNary S, Lehman A: Substance abuse and family relationships of persons with severe mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:456–458, 1995Google Scholar

34. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Pub no SMA-03-3832. Rockville, Md, Department of Health and Human Services, President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003Google Scholar

35. Spaniol L, Wewiorski NJ, Gagne C, et al: The process of recovery from schizophrenia. International Review of Psychiatry 14:327–336, 2002Google Scholar

36. Ralph RO, Corrigan PW (eds): Recovery in Mental Illness: Broadening Our Understanding of Wellness. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2005Google Scholar

37. Dixon L, Lyles A, Scott J, et al: Services to families of adults with schizophrenia: from treatment recommendations to dissemination. Psychiatric Services 50:233–238, 1999Google Scholar

38. Kohn-Wood LP, Wilson MN: The context of caretaking in rural areas: family factors influencing the level of functioning of seriously mentally ill patients living at home. American Journal of Community Psychology 36:1–13, 2005Google Scholar

39. Dixon L: Providing services to families of persons with schizophrenia: present and future. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 2:3–8, 1999Google Scholar

40. Glynn SM, Cohen AN, Dixon LB, et al: The potential impact of the recovery movement on family interventions for schizophrenia: opportunities and obstacles. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32:451–463, 2006Google Scholar

41. Young AS, Sullivan G, Burnam MA, et al: Measuring the quality of outpatient treatment for schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:611–617, 1998Google Scholar

42. Resnick SG, Rosenheck RA, Dixon L, et al: Correlates of family contact with the mental health system: allocation of a scarce resource. Mental Health Services Research 7:113–121, 2005Google Scholar

43. Dixon L, Lucksted A, Stewart B, et al: Therapists' contacts with family members of persons with severe mental illness in a community treatment program. Psychiatric Services 51:1449–1451, 2000Google Scholar

44. Prince JD: Family involvement and satisfaction with community mental health care of individuals with schizophrenia. Community Mental Health Journal 41:419–430, 2005Google Scholar

45. Bogart T, Solomon P: Procedures to share treatment information among mental health providers, consumers, and families. Psychiatric Services 50:1321–1325, 1999Google Scholar