Service Utilization Differences for Axis I Psychiatric and Substance Use Disorders Between White and Black Adults

Racial and ethnic differences in patterns of service utilization for mental disorders, especially among disadvantaged groups, must be understood in order to address disparities in the United States and provide targeted prevention and intervention strategies. Previous large-scale epidemiologic studies of psychiatric disorders indicate that individuals in the black population are less likely than those in the white population to receive professional mental health treatment ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ). In particular, persons who are black are less likely to receive treatment for mood and anxiety disorders, whether defined broadly as any professional treatment ( 2 , 4 , 7 ) or specifically as talking with a mental health professional ( 4 , 8 , 9 ) or using prescription medication ( 8 , 10 ). Fewer epidemiologic studies have examined racial and ethnic disparities in alcohol and drug treatment utilization, and results were inconsistent ( 11 , 12 , 13 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ) because of differences in measurement and design. Several studies were able to estimate racial and ethnic differences in service utilization among individuals with a particular alcohol or drug diagnosis in the general population. Among three U.S. samples of adults diagnosed with an alcohol disorder, two studies comparing a black group with others suggested no racial or ethnic differences in alcohol treatment ( 19 , 20 ), whereas one found no racial or ethnic differences overall but found less alcoholism treatment among black individuals with higher levels of alcohol severity ( 21 ). Data from a general population sample indicated no overall racial or ethnic differences in drug treatment among individuals with a drug use disorder, although black and white populations were not specifically compared ( 22 ).

As a theoretical framework to examine effects of race and ethnicity on service utilization, the Andersen behavioral model of health service treatment contact is the most extensively studied model of service utilization ( 23 , 24 ). This model posits that service utilization is a function of predisposing characteristics (such as gender, age, and race and ethnicity), enabling factors (such as income, education, health insurance, urbanicity or region, and having a regular source of care), and need for services (such as symptom severity, comorbidity, and perceived need for care). Although this model has received much theoretical attention, few nationally representative epidemiologic samples have empirically tested it. Moreover, small samples of respondents with a substance use disorder within racial and ethnic groups have limited the ability to detect effects or control for patterns related to relevant confounders. Studies that have applied the Andersen model in national samples found overall disparities for minority groups; differences within diagnosis remain unstudied ( 25 ).

Although prior studies have identified disparities in treatment utilization, many aspects of racial differences in service utilization remain unclear. Mood and anxiety disorders and substance use disorders differ in their symptoms, appropriate treatments, and settings where treatment is provided. Whereas differences in service utilization for a specific diagnosis of depression are extensively documented ( 2 , 10 ), most studies examining treatment disparities collapse the outcome measure across all disorders, making it unclear whether black-white racial disparities are in the mood and anxiety domain or in the alcohol and drug domain. If category of diagnosis moderates racial and ethnic differences, this information can provide more specific avenues for policy and treatment interventions. For instance, the information can refine diagnostic domains in which disparities exist, specify theory concerning causal pathways to disparities, and ultimately lead to more equal distribution of services.

Difficulty in accurately measuring differences between black and white individuals with substance use disorders also arises in studies based on the World Mental Health version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI) such as the National Comorbidity Survey Replication study (NCS-R) ( 26 ). In a deviation from DSM-IV, the WMH-CIDI does not assess substance dependence among those without substance abuse ( 25 , 27 , 28 ). Because approximately one-third of patients diagnosed as having substance dependence do not meet criteria for substance abuse ( 25 , 27 , 28 , 29 ), and alcohol dependence without abuse is more likely to occur among black individuals than white individuals ( 27 ), NCS-R data cannot provide information on racial differences in service utilization for alcohol or drug dependence.

To overcome these methodological problems, we examined racial and ethnic differences in service utilization for mood, anxiety, alcohol use, and drug use disorders in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). The goals of these analyses were to determine whether black and white populations differed in treatment across these disorders and to determine whether differences observed persisted after other elements described in the Andersen model were controlled for, especially if these elements differed by race. The large sample and complete measurement of alcohol and drug dependence as well as abuse, as defined by DSM-IV, allowed for an accurate and statistically powerful investigation of racial and ethnic differences in treatment use.

Methods

Sample

The sample was drawn from the 2001–2002 NESARC, a representative U.S. survey of civilian noninstitutionalized persons ages 18 and older. Details of the sampling framework are described elsewhere ( 30 , 31 , 32 ). The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) sponsored the study and supervised the fieldwork, which was conducted by the U.S. Bureau of the Census. Young adult and black populations were oversampled; the overall response rate was 81%. The research protocol received full ethical review and approval from the U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Office of Management and Budget. Our study focused on the white and black respondents (N= 32,752). Details on the interviewers, training, and fieldwork quality control are described elsewhere ( 30 ).

Measures

NIAAA's Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV (AUDADIS-IV) ( 33 ) includes detailed assessment of DSM-IV abuse and dependence criteria for alcohol and ten classes of drugs. Lifetime diagnoses were derived with computer algorithms operationalizing DSM-IV ( 34 ) criteria. Time frames for diagnosis covered the past 12 months or the period before the past 12 months. Because the direction and magnitude of associations among respondents with diagnoses of abuse and dependence were similar, the diagnoses were combined. The reliability and validity of substance use diagnoses were examined via test-retest studies and clinical reappraisals conducted by psychiatrists ( 35 ). These had excellent reliability in clinical and general population samples ( 30 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 ). Validity was further demonstrated in various studies, including the World Health Organization-National Institutes of Health Reliability and Validity Study ( 36 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 ) and others ( 29 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 ).

DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders included primary major depression, dysthymia, mania, hypomania, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, and specific phobia. The reliability and validity of mood and anxiety disorder diagnoses ranged from fair (for specific phobia, κ =.42) to good (for major depressive disorder κ =.65) ( 30 , 35 , 37 ). The reliability of diagnosis of anxiety disorders is similar to those of other instruments designed for national surveys, such as the CIDI and the Diagnostic Interview Schedule ( 51 , 52 ). In addition, depression diagnoses were reliable and have been validated by psychiatric diagnosis in Puerto Rico ( 35 ), which provides support for the instrument across racial and ethnic and cultural groups. The Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short Form version 2, a mental disability score, further validated diagnoses via controlled linear regressions ( 31 , 32 , 53 , 54 ).

There is substantial evidence for reliability and validity of the alcohol and drug diagnoses across racial and ethnic groups ( 49 ), including one study specifically demonstrating that race was unrelated to the reliability of diagnosis of alcohol use disorders ( 55 ). Data from the World Health Organization study, which spanned 11 countries, and the Puerto Rico study ( 35 ) provide further evidence of the cross-cultural reliability and validity of the diagnoses of alcohol and drug use disorders ( 36 , 38 , 40 , 41 ).

The outcome variables consisted of lifetime service utilization for specific DSM-IV disorders. Respondents who ever used alcohol or drugs were asked about 13 types of services: self-help (such as Alcoholics Anonymous); family services; employee assistance program; clergy; alcohol or drug detoxification; inpatient ward; outpatient clinic; rehabilitation program; halfway house; private physician, psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, or other professional; emergency visit; crisis center; and methadone program (drug users). For this analysis, service type was combined across categories because direction of effect was similar within service types.

Questions regarding mental health service utilization for mood and anxiety disorders were asked of all respondents screened into the relevant module. These questions covered outpatient services (counselor, therapist, physician, or other professional), inpatient services (staying overnight or longer in a hospital), emergency services, and prescribed medication. Mood or anxiety disorder service types were also combined across categories because the direction of effect was similar within service types.

Statistical analysis

Prevalences and standard errors were computed for service utilization in the full sample of anyone screened into a diagnostic section (regardless of diagnosis), those with any diagnosis, and anyone with specific diagnostic profiles. Given that respondents with certain disorders may use services other than those directly intended for that disorder, we examined service utilization among those with any axis I disorder in order to capture racial and ethnic differences among all respondents using mental health services. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were derived from logistic regressions with SUDAAN software version 9.1 ( 56 ) to obtain standard errors adjusted for the complex sample design.

Control variables were selected on the basis of the conceptual framework provided by the Andersen model of service utilization ( 23 , 24 ), reflecting predispositional factors (sex and age) and enabling factors (education, marital status, urbanicity, region, and current insurance status). Income was tested as an effect modifier of the relationship between race and ethnicity and treatment. Because no significant interactions were detected, income was controlled as an enabling factor in all models. To address need for treatment, each model contained a disorder-specific severity indicator consisting of the number of disorder-specific DSM-IV symptoms.

Results

Distribution of predispositional factors

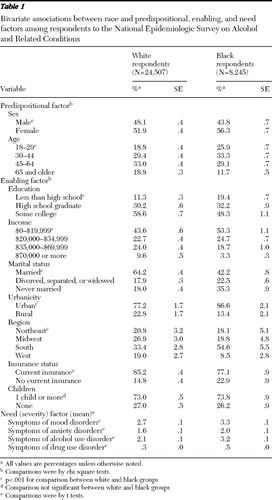

In the full sample of respondents (see Table 1 ), there were significantly more men in the white group than in the black group ( χ2 =19.7, df=1, p<.001). On average, black respondents were younger ( χ2 =74.5, df=3, p<.001).

|

Distribution of enabling factors

Black respondents were more likely than whites to have not completed high school ( χ2 =65.7, df=2, p<.001) and to have lower income ( χ2 =74.0, df=3, p<.001) and were less likely to have health insurance ( χ2 =44.7, df=1, p<.001). Black respondents were more likely to live in urban environments ( χ2 =19.6, df=1, p<.001) and were overrepresented in the South ( χ2 =53.8, df=3, p<.001).

Distribution of need (severity)

White respondents had significantly more symptoms for mood (t=5.6, df=65, p<.001), anxiety (t=4.9, df=65, p<.001), and alcohol use (t=13.8, df=65, p<.001) disorders. Black respondents had significantly higher drug use disorder symptoms (t=5.7, df=65, p<.001).

Associations with service utilization

Predispositional, enabling, and need factors were all significantly (p<.05) associated with service utilization in bivariate analysis (not shown). Those having lower income, residing in the western region of the United States, and having more disorder-specific symptoms were more likely to use each diagnosis-specific treatment type. Women, respondents in middle age, and respondents who were widowed, separated, or divorced were more likely to utilize mood and anxiety services. Men, younger respondents, respondents who had never married, and respondents with insurance were more likely to utilize alcohol treatment services or drug treatment services.

Likelihood of treatment utilization in diagnostic subsets

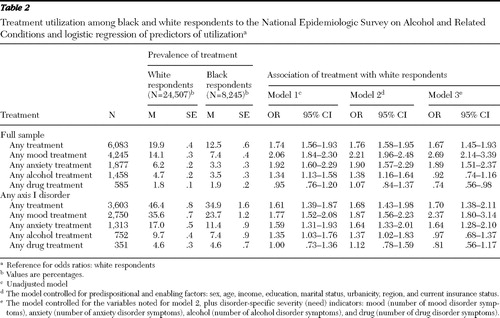

All screened respondents. Lifetime prevalence of any service utilization for mental or substance use disorders was 19.9% among white respondents and 12.5% among black respondents ( Table 2 ). Three models are presented. Model 1 indicates the unadjusted association between race and ethnicity and treatment, model 2 indicates that the association controlled for predispositional and enabling factors, and model 3 further controlled for need (severity). In all three models, the likelihood of any service utilization was significantly higher among white respondents than black respondents. In addition, the white group was significantly more likely than the black group to receive treatment services for mood disorders (OR= 2.69) and anxiety disorders (OR= 1.89) with all other factors controlled for (model 3). In contrast service utilization for alcohol treatment was not significantly different by race; however, white respondents were significantly less likely to utilize drug treatment services (OR=.74). Further subdivision into inpatient care versus outpatient care yielded similar magnitude and direction of effect (not shown).

|

Respondents with any axis I disorder. Among persons with any axis I disorder, the pattern of results paralleled that seen in the full sample. In fully adjusted models (model 3), white respondents were more likely than black respondents to utilize services for mood and anxiety disorders, and there were no significant differences between groups in alcohol or drug treatment utilization.

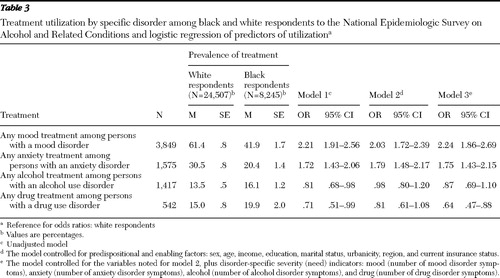

Respondents with a mood or anxiety disorder. Among respondents with mood disorders, 61.4% of white respondents and 41.9% of black respondents sought treatment ( Table 3 ). In the fully adjusted model (model 3) white respondents were significantly more likely than black respondents to use such services (OR=2.24). Among persons with anxiety disorders, white respondents were significantly more likely than black respondents to use such services in fully adjusted models (OR=1.75).

|

Respondents with a drug or alcohol use disorder. Among respondents with an alcohol disorder, 13.5% of whites and 16.1% of blacks utilized alcohol treatment services ( Table 3 ). Whereas with the unadjusted model black respondents were less likely than white respondents to utilize these services ( Table 3 , model 1), these differences were explained by predispositional and enabling factors ( Table 3 , models 2 and 3). Among respondents with a drug use disorder, 15.0% of the white group and 19.9% of the black group utilized drug services. Controlling for all predisposing, enabling and need factors, analyses showed that white respondents were significantly less likely than black respondents to utilize drug treatment services (OR=.64). Subdivision of treatment into more specific categories yielded similar magnitude and direction of effect.

Discussion

The major finding of this study is that service utilization patterns among black and white respondents depended on the specific disorder and type of treatment considered. Black respondents were consistently less likely than white respondents to receive services for mood and anxiety disorders, even after we adjusted for predispositional, enabling, and need factors associated with treatment utilization. This was true for the full sample, persons with any axis I disorder, and those whose need was specific—in other words, a mood or anxiety disorder—confirming prior findings that the black population receives fewer mental health services than the white population for treatment of mood and anxiety disorders ( 1 , 2 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 8 , 57 , 58 , 59 ).

In contrast no evidence emerged of service utilization disparity between black and white respondents for alcohol or drug use disorders, despite statistical power to detect a difference. Black respondents in the full sample and among respondents with a drug use disorder were significantly more likely than white respondents to receive drug services once differences between the groups on predispositional, enabling, and need factors were controlled for. Some general population studies on race differences in substance treatment indicated no differences ( 3 , 4 , 5 ), whereas others have suggested that the black population is less likely to utilize mental health services for substance use disorders ( 17 , 18 , 60 ); however, these studies lacked specific diagnostic information on a full range of adults in a national sample. It should be noted that less than 20% of people with a drug or alcohol use disorder used any service, which highlights the disparity of service utilization across racial and ethnic lines.

The contrast between lower service utilization rates for black respondents with mood and anxiety disorders and equal to or higher rates than whites with alcohol use or drug use disorders raises important questions about differential service utilization patterns. Although several past studies showed that racial and ethnic differences in mental health service utilization are substantially attenuated by socioeconomic status differences ( 7 , 11 , 15 ), this investigation indicated that disparities persisted despite differences in income or education. Other explanations may include cultural and policy-level factors. Culturally, black communities may react more negatively than white communities to hazardous drinking ( 61 ) and provide greater social support for sobriety ( 62 ). Cultural influences may affect conceptions of causes and treatments of mental health problems, including perceived need for treatment ( 11 ), resulting in differences between black and white communities ( 63 ).

Medical research has consistently shown that black persons are more likely to distrust the medical community and the health care system ( 16 , 64 ). There may also be important subgroup differences within the black community; for example, recent evidence indicates that African Americans may utilize more mental health services than Caribbean blacks ( 65 ). Future studies using more refined racial and ethnic categories could further specify mediators of racial and ethnic differences, including nativity and acculturation, which may affect perception of the mental health care system. Racial and ethnic attitudes toward anxiety or depression have not been directly compared with attitudes toward alcohol or drug use disorders, an important direction for future research.

Furthermore, questions about the reasons for the different patterns of services in black and white populations could focus on potential confounding caused by specific subgroups within the general samples we examined. This is addressed in part elsewhere ( 59 ) by examining treatment disparities among the subgroup of whites and blacks that had mood or anxiety disorder co-occurring with an alcohol or drug use disorder. In this subgroup analysis, we also found significant differences: white respondents were 2.05 times as likely as black respondents to use mood or anxiety services during their lifetime and .80 times as likely to use drug services, and again we found no difference in using alcohol services (OR=.99). Thus patterns of racial-ethnic differences in the comorbid subgroup were generally similar to the patterns shown above, despite the potential greater severity of illness among those with more than one type of disorder. This is important information because comorbidity is a strong predictor of treatment entry. Further, we examined whether the patterns of axis I treatment utilization were different among the subset of respondents with an axis II diagnosis. Results were generally similar, although there were no significant racial and ethnic differences in drug treatment service utilization among individuals with a drug use disorder. Taken together, the results of both investigations indicate that racial and ethnic differences in treatment utilization are not substantially attenuated or modified by comorbidity, and furthermore, the magnitude of difference is remarkably similar in the comorbid subgroups compared with the broader group of all individuals who received a diagnosis as analyzed in this study.

At a policy level, social coercion through law enforcement—an "external environment" enabling characteristic of the Andersen model ( 23 )—might indirectly explain higher service utilization for substance use disorders among black individuals because drug policies and laws disproportionately affect black communities ( 66 , 67 ). At similar toxicology levels, more persons in minority groups than whites are mandated to receive alcohol treatment by the criminal justice system ( 68 , 69 ). Also, some evidence indicates that black persons who enter the mental health system are more likely than whites to have entered through coercion ( 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 ). Future studies should determine how social pressure and legal coercion influence entry into services for different disorders and how this affects larger perceptions of treatment for the different disorders by race and ethnicity. In addition, mental health service delivery systems have changed over time; determining that disparities vary across changes in the mental health service system over time would suggest mechanisms through which disparities exist.

We now address limitations of the study. First, in the examination of lifetime disorders and service utilization, respondents' recall bias might have affected estimates, particularly among older respondents. To investigate this, we reran our analysis limited to current (past 12 months) disorders. The magnitude and direction of effects were virtually unchanged, suggesting that recall bias did not substantially affect our estimates. Smaller numbers of respondents in diagnostic categories limited the power to detect effects, so for this reason, as well as the high quality of the lifetime diagnoses provided by the AUDADIS-IV ( 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 55 ), we reported lifetime measures. Recall bias can also affect the type and timing of treatment reported. We assume that there would be no racial or ethnic difference in recall, but evidence (which is lacking) on the accuracy of this assumption would assist in interpreting the results.

Second, individuals institutionalized for mental disorders or incarcerated throughout the data collection were not included; disparities in institutionalization could bias the findings. Persons from the black community have higher incarceration rates, but studies are inconsistent on whether persons belonging to minority groups receive fewer mental health services in prison than whites do ( 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 ). Racial and ethnic differences in rates of long-term mental health institutionalization are also unclear ( 15 , 78 ), so institutionalization effects on our findings are uncertain. Third, these data were cross-sectional. Longitudinal data would allow prospective examination of factors predicting entry into mental health services, which will be possible when NESARC follow-up data become available.

The NESARC did not focus solely on treatment utilization; additional detail on treatment in future surveys would be helpful. However, differences in questions regarding mood and anxiety treatment and alcohol or drug treatment utilization reflect true differences in both the services and service delivery systems for these disorders. In addition, racial and ethnic differences reflect differences in services available as well as individual treatment choices. Future surveys should include information on services available to the respondent. Finally, this study addressed disparities in service utilization but could not address other important disparities, such as quality, appropriateness, and efficacy of care. Although disparities in quality of care within treatment services have been shown ( 68 ), this study highlights disparities in receiving any care at all.

Conclusions

The study has important strengths, including its large sample, detailed assessment of service utilization, and state-of-the-art diagnostic assessment that corrected for diagnostic problems of prior studies ( 26 ). These advantages allowed us to show that racial and ethnic differences in service utilization varied by disorder type and that important information is lost if disorders are collapsed across categories. Further, the attention to potential confounding factors represents a substantial contribution in the understanding of how predispositional, enabling, and need factors may affect racial and ethnic differences in treatment utilization. Finally, the NESARC sample allowed investigation of service contact patterns for other racial and ethnic minority groups, and that research is now under way. Although this analysis intended to focus on the two largest racial and ethnic groups in the United States, it is important to understand mental health service utilization among Asian, Hispanic, and other racial and ethnic groups in order to elucidate the entirety of health disparities in this country. Findings from these populations will assist in developing interventions to increase treatment among underserved racial and ethnic groups. This study also has important policy implications. Few individuals with DSM-IV diagnoses utilize treatment services, especially individuals with substance use disorders. Therefore, efforts to engage individuals in need are necessary across racial and ethnic groups. In addition, targeted efforts to recruit persons from racial and ethnic minority groups with mood and anxiety disorders into treatment may improve disparities in this treatment area.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported in part by grant K05-AA-014223 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and by support from New York State Psychiatric Institute. The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions was conducted and funded by NIAAA with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. This study was, in part, funded by the intramural program of the National Institutes of Health and NIAAA. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any sponsoring organization, agencies, or the U.S. government.

1. Swartz MS, Wagner HR, Swanson JW, et al: Administrative update: utilization of services: I. comparing use of public and private mental health services: the enduring barriers of race and age. Community Mental Health Journal 34:133–144, 1998Google Scholar

2. Sussman LK, Robins LN, Earls F: Treatment-seeking for depression by black and white Americans. Social Science and Medicine 24:187–196, 1987Google Scholar

3. Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Powe NR, et al: Mental health service utilization by African Americans and Whites: the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area Follow-Up. Medical Care 37:1034–1045, 1999Google Scholar

4. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al: Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:629–640, 2005Google Scholar

5. Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, et al: Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:603–613, 2005Google Scholar

6. Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, et al: Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. New England Journal of Medicine 352:2515–2523, 2005Google Scholar

7. Harris KM, Edlund MJ, Larson S: Racial and ethnic differences in the mental health problems and use of mental health care. Medical Care 43:775–784, 2005Google Scholar

8. Lasser KE, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler SJ, et al: Do minorities in the United States receive fewer mental health services than whites? International Journal of Health Services 32:567–578, 2002Google Scholar

9. Olfson M, Pincus HA: Outpatient psychotherapy in the United States, I: volume, costs, and user characteristics. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:1281–1288, 1994Google Scholar

10. Olfson M, Klerman GL: The treatment of depression: prescribing practices of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. Journal of Family Practice 35:627–635, 1992Google Scholar

11. Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Mechanic D: Perceived need and help-seeking in adults with mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:77–84, 2002Google Scholar

12. Booth BM, Kirchner J, Fortney J, et al: Rural at-risk drinkers: correlates and one-year use of alcoholism treatment services. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 61:267–277, 2000Google Scholar

13. Kaskutas LA, Weisner C, Caetano R: Predictors of help seeking among a longitudinal sample of the general population, 1984–1992. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 58:155–161, 1997Google Scholar

14. Weisner CM, Matzger H, Tam T, et al: Who goes to alcohol and drug treatment? Understanding utilization within the context of insurance. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 63:673–682, 2002Google Scholar

15. Padgett DK, Patrick C, Burns BJ, et al: Ethnicity and the use of outpatient mental health services in a national insured population. American Journal of Public Health 84:222–226, 1994Google Scholar

16. Cooper LA, Beach MC, Johnson RL, et al: Delving below the surface: understanding how race and ethnicity influence relationships in health care. Journal of General Internal Medicine 21(suppl 1):S21–S27, 2006Google Scholar

17. Wu LT, Ringwalt CL, Williams CE: Use of substance abuse treatment services by persons with mental health and substance use problems. Psychiatric Services 54:363–369, 2003Google Scholar

18. Heflinger CA, Chatman J, Saunders RC: Racial and gender differences in utilization of Medicaid substance abuse services among adolescents. Psychiatric Services 57:504–511, 2006Google Scholar

19. Cohen E, Feinn R, Arias A, et al: Alcohol treatment utilization: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 86:214–221, 2007Google Scholar

20. Schmidt LA, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, et al: Ethnic disparities in clinical severity and services for alcohol problems: results from the National Alcohol Survey. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 31:48–56, 2007Google Scholar

21. Grant BF: Toward an alcohol treatment model: a comparison of treated and untreated respondents with DSM-IV alcohol use disorders in the general population. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 20:372–378, 1996Google Scholar

22. Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, et al: Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry 64:566–576, 2007Google Scholar

23. Andersen RM: Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36:1–10, 1995Google Scholar

24. Andersen RM, Davidson PL: Measuring access and trends, in Changing the US Health Care System. Edited by Andersen RM, Rice TH, Kominski GF. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1996Google Scholar

25. Grant BF, Compton WM, Crowley TJ, et al: Errors in assessing DSM-IV substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 64:379–380, 2007Google Scholar

26. Kessler RC, Ustun TB: The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:93–121, 2004Google Scholar

27. Hasin DS, Grant BF: The co-occurrence of DSM-IV alcohol abuse in DSM-IV alcohol dependence: NESARC results on heterogeneity that differs by population subgroup. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:891–896, 2004Google Scholar

28. Hasin DS, Hatzenbuehler M, Smith S, et al: Co-occurring DSM-IV drug abuse in DSM-IV drug dependence: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 80:117–123, 2005Google Scholar

29. Grant BF, Harford TC, Hasin DS, et al: DSM-III-R and the proposed DSM-IV alcohol use disorders, United States 1988: a nosological comparison. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 16:215–221, 1992Google Scholar

30. Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, et al: The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 71:7–16, 2003Google Scholar

31. Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al: Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:807–816, 2004Google Scholar

32. Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, et al: Prevalence, correlates, co-morbidity, and comparative disability of DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder in the USA: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychological Medicine 35:1747–1759, 2005Google Scholar

33. Grant BF, Dawson DA, Hasin DS: The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule—DSM-IV Version. Bethesda, Md, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2001Google Scholar

34. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

35. Canino GJ, Bravo M., Ramírez R, et al: The Spanish Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): reliability and concordance with clinical diagnoses in a Hispanic population. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 60:790–799, 1999Google Scholar

36. Chatterji S, Saunders JB, Vrasti R, et al: Reliability of the alcohol and drug modules of the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule—Alcohol/Drug—Revised (AUDADIS-ADR): an international comparison. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 47:171–185, 1997Google Scholar

37. Grant BF, Harford TC, Dawson DA, et al: The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 39:37–44, 1995Google Scholar

38. Hasin D, Grant BF, Cottler L, et al: Nosological comparisons of alcohol and drug diagnoses: a multisite, multi-instrument international study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 47:217–226, 1997Google Scholar

39. Vrasti R, Grant BF, Chatterji S, et al: Reliability of the Romanian version of the alcohol module of the WHO Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities: Interview Schedule—Alcohol/Drug—Revised. European Addiction Research 4:144–149, 1998Google Scholar

40. Cottler LB, Grant BF, Blaine J, et al: Concordance of DSM-IV alcohol and drug use disorder criteria and diagnoses as measured by AUDADIS-ADR, CIDI and SCAN. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 47:195–205, 1997Google Scholar

41. Pull CB, Saunders JB, Mavreas V, et al: Concordance between ICD-10 alcohol and drug use disorder criteria and diagnoses as measured by the AUDADIS-ADR, CIDI and SCAN: results of a cross-national study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 47:207–216, 1997Google Scholar

42. Hasin DS, Schuckit MA, Martin CS, et al: The validity of DSM-IV alcohol dependence: what do we know and what do we need to know? Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 27:244–252, 2003Google Scholar

43. Grant BF: DSM-IV, DSM-III-R, and ICD-10 alcohol and drug abuse/harmful use and dependence, United States, 1992: a nosological comparison. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 20:1481–1488, 1996Google Scholar

44. Grant BF, Harford TC: The relationship between ethanol intake and DSM-III alcohol use disorders: a cross-perspective analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse 1:231–252, 1988Google Scholar

45. Grant BF, Harford TC: The relationship between ethanol intake and DSM-III-R alcohol dependence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 51:448–456, 1990Google Scholar

46. Hasin DS, Grant B: Nosological comparisons of DSM-III-R and DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in a clinical facility: comparison with the 1988 National Health Interview Survey results. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 18:272–279, 1994Google Scholar

47. Hasin D, Paykin A: Alcohol dependence and abuse diagnoses: concurrent validity in a nationally representative sample. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 23:144–150, 1999Google Scholar

48. Hasin DS, Van Rossem R, McCloud S, et al: Differentiating DSM-IV alcohol dependence and abuse by course: community heavy drinkers. Journal of Substance Abuse 9:127–135, 1997Google Scholar

49. Hasin D, Carpenter KM, McCloud S, et al: The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a clinical sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 44:133–141, 1997Google Scholar

50. Hasin D, Van Rossem R, McCloud S, et al: Alcohol dependence and abuse diagnoses: validity in community sample heavy drinkers. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 21:213–219, 1997Google Scholar

51. Haro J, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez S, Brugha TS, et al: Concordance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0 (CIDI 3.) with standardized clinical assessments in the WHO World Mental Health surveys. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 15:167–180, 2006Google Scholar

52. Semler G, Wittchen HU, Joschke K, et al: Test-retest reliability of a standardized psychiatric interview (DIS/CIDI). European Archives of Psychiatry and Neurological Science 236:214–222, 1987Google Scholar

53. Grant BF, Stinson FS, Hasin DS, et al: Immigration and lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV psychiatric disorders among Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:1226–1233, 2004Google Scholar

54. Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, et al: Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:1097–1106, 2005Google Scholar

55. Hasin D, McCloud S, Li Q, et al: Cross-system agreement among demographic subgroups: DSM-III, DSM-III-R, DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnoses of alcohol use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 41:127–135, 1996Google Scholar

56. Software for Survey Data Analysis (SUDAAN), version 9.1. Research Triangle Park, NC, Research Triangle Institute, 2004Google Scholar

57. Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, et al: The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: implications for prevention and service utilization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:17–31, 1996Google Scholar

58. Alegria M, Canino G, Rios R, et al: Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino whites. Psychiatric Services 53:1547–1555, 2002Google Scholar

59. Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM, Narrow WE, et al: Racial/ethnic disparities in service utilization for individuals with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders in the general population. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, in pressGoogle Scholar

60. Wells K, Klap R, Koike A, et al: Ethnic disparities in unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health care. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:2027–2032, 2001Google Scholar

61. Herd D: Drinking by Black and White women: results from a national survey. Social Problems 35:493–505, 1988Google Scholar

62. Brower KJ, Carey TL: Racially related health disparities and alcoholism treatment outcomes. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 27:1365–1367, 2003Google Scholar

63. Millet PE, Sullivan BF, Schwebel AI, et al: Black Americans' and White Americans' views of the etiology and treatment of mental health problems. Community Mental Health Journal 32:235–242, 1996Google Scholar

64. Johnson RL, Saha S, Arbelaez JJ, et al: Racial and ethnic differences in patient perceptions of bias and cultural competence in health care. Journal of General Internal Medicine 19:101–110, 2004Google Scholar

65. Neighbors HW, Caldwell C, Williams DR, et al: Race, ethnicity, and the use of services for mental disorders: results from the National Survey of American Life. Archives of General Psychiatry 64:485–494, 2007Google Scholar

66. Cooper H, Moore L, Gruskin S, et al: Characterizing perceived police violence: implications for public health. American Journal of Public Health 94:1109–1118, 2004Google Scholar

67. Iguchi MY, Bell J, Ramchand RN, et al: How criminal system racial disparities may translate into health disparities. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 16:48–56, 2005Google Scholar

68. Schmidt L, Greenfield T, Mulia N: Unequal treatment: racial and ethnic disparities in alcoholism treatment services. Alcohol Research and Health 29:49–54, 2006Google Scholar

69. Chasnoff IJ, Landress HJ, Barrett ME: The prevalence of illicit-drug or alcohol use during pregnancy and discrepancies in mandatory reporting in Pinellas County, Florida. New England Journal of Medicine 322:1202–1206, 1990Google Scholar

70. Akutsu PD, Snowden LR, Organista KC: Referral patterns to ethnic-specific and mainstream mental health programs for Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites. Journal of Counseling Psychology 43:56–64, 1996Google Scholar

71. Takeuchi DL, Cheung MK: Coercive and voluntary referrals: how ethnic minority adults get into mental health treatment. Ethnicity and Health 3:149–158, 1998Google Scholar

72. Breaux C, Ryujin D: Use of mental health services by ethnically diverse groups with the United States. Clinical Psychologist 52:4–15, 1999Google Scholar

73. Snowden LR, Cheung FK: Use of inpatient mental health services by members of ethnic minority groups. American Psychologist 45:347–355, 1990Google Scholar

74. Coid J, Petruckevitch A, Bebbington P, et al: Ethnic differences in prisoners. 2: risk factors and psychiatric service use. British Journal of Psychiatry 181:481–487, 2002Google Scholar

75. Steadman HJ, Holohean EJ, Dvoskin J: Estimating mental health needs and service utilization among prison inmates. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 19:297–307, 2001Google Scholar

76. Jordan BK, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, et al: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among incarcerated women. II. convicted felons entering prison. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:513–519, 1996Google Scholar

77. Staton M, Leukefeld C, Webster JM: Substance use, health and mental health: problems and service utilization among incarcerated women. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 47:224–239, 2003Google Scholar

78. Leese M, Thornicroft G, Shaw J, et al: Ethnic differences among patients in high-security psychiatric hospitals in England. British Journal of Psychiatry 188:380–385, 2006Google Scholar