Gender Differences in Health-Related Quality of Life for Veterans With Serious Mental Illness

Serious mental illness, a diagnostic category that includes schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and schizoaffective disorder, affects 5.4% of the U.S. population. Compared with individuals without serious mental illness, those with serious mental illness have higher mortality rates, increased medical comorbidities, and higher health care expenditures ( 1 , 2 ). Those with a serious mental illness are also more likely to be homeless ( 3 ), are less likely to be employed ( 4 ), and are often reliant upon Social Security income as a main source of financial support.

As might be expected, compared with people without serious mental illness, those with serious mental illness report lower quality of life across several domains, including employment, education, and social relationships ( 5 , 6 , 7 ). In particular, individuals with serious mental illness have lower health-related quality of life (HRQOL) ( 8 ). HRQOL is a component of quality-of-life measures that assesses aspects of quality of life that are directly related to health and illness states ( 9 ). Measuring HRQOL among people with serious mental illness is critical for designing personalized treatment strategies, assessing improvement, and ensuring optimal outcomes for this population, because low HRQOL has been associated with higher mortality ( 10 ) and greater health care utilization ( 11 ).

One critical application of HRQOL research is to understand how serious mental illness differentially affects women and men. In the Department of Veterans Affairs health care system, where the number of female enrollees has increased substantially in recent years ( 12 ), understanding the differences in HRQOL between men and women with serious mental illness is especially important. Women now make up 15% of U.S. veterans and 7.4% of U.S veterans with serious mental illnesses ( 13 ). In order to design a system of care that best serves the needs of all veterans with serious mental illnesses, attention must be paid to differences in the effect of serious mental illness on the lives of men and women and the resultant differing needs they may have.

Studies of gender differences in HRQOL in a variety of populations have found that women tend to report lower HRQOL than men. For example, recent studies of HRQOL in community-based samples have found that women are less likely than men to report that their overall health is "excellent" ( 14 ) and have lower scores than men on all of the HRQOL subscales of the 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) ( 15 ). A study of older adults found that women reported worse HRQOL than men on the Nottingham Health Profile (mean scores: 28.3 for women and 16.7 for men, Cohen's d=-2.6). (Possible scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating worse HRQOL.) Similarly, studies of adolescents ( 16 ), patients with HIV-AIDS ( 17 ), and patients with cystic fibrosis ( 18 ) have found that women report lower HRQOL than men.

Little is known, however, about whether and how HRQOL differs between men and women with serious mental illness. The few studies that have examined the effect of gender on HRQOL in seriously mentally ill populations have found that women report worse HRQOL than men across multiple domains ( 19 , 20 ). In particular, Robb and colleagues ( 19 ) found that women with bipolar disorder reported lower scores on all subscales of the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) SF-20, as well as significantly increased pain (mean scores: 65.9±4.0 for women versus 79.3±6.1 for men, Cohen's d=2.6) and worse physical health (mean scores: 78.5±3.9 for women versus 90.1±3.2 for men, Cohen's d=-3.5). (Possible scores on the subscales range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better HRQOL.) This study was limited by a small sample (N=69); other studies that have explored gender differences in HRQOL in this population have similarly suffered from small samples, limiting their generalizability ( 20 ). These studies were also limited in their ability to control for patient factors that can affect HRQOL ( 21 ).

By using data from the National Psychosis Registry at the VA, the study presented here was able to overcome the small-sample problems of previous studies and was able to control for numerous patient factors. We examined HRQOL across several domains for male and female veterans with serious mental illness diagnoses who were receiving care through the VA and estimated the differences in HRQOL by gender, after controlling for patient factors.

Methods

Study design and setting

The VA National Psychosis Registry ( 13 ), developed and maintained by the VA's National Serious Mental Illness Treatment Research and Evaluation Center, contains administrative data on diagnosis, utilization, and cost for all VA patients with a recorded serious mental illness diagnosis from fiscal year (FY) 1988 to the present (N=728,521 through FY 2004).

Our study population consisted of VA patients in the National Psychosis Registry with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder who completed the Large Health Survey of Veteran Enrollees (LHSV) in FY 1999 ( 22 , 23 ). The LHSV is the largest survey ever conducted of veterans using VA health services. It was administered in 1999 to a national random sample of 1.5 million veteran enrollees who were mailed a survey that included a comprehensive assessment of health and functional status and demographic variables. Of the 1,406,049 surveyed who were living and had valid names and addresses, 63% (N= 887,775) responded ( 24 ). Our final sample included the 18,017 veterans who responded to the survey and who were included in the National Psychosis Registry. Because this study involved a secondary data analysis, we received a waiver of informed consent for this study from the VA Institutional Review Board.

Measures

The outcome variables in these analyses are assessments of health-related quality of life, using the MOS SF-36 ( 25 ), which was included as part of the LHSV. From the SF-36, we specified variables and scales particularly relevant to the assessment of HRQOL. First, we assessed overall mental and physical health using the scores on three sections of the SF-36: the mental component summary (MCS), the physical component summary (PCS), and activities of daily living (ADLs). Second, to determine differences in subjective health-related well-being, an important indicator of morbidity ( 26 ), we assessed global health status with the question, "In general would you say your health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?" Third, we assessed physical functioning by using individual questions about ADL limitations, the amount that health interfered with normal social activities, and the extent of bodily pain. Finally, we assessed self-perceived health status by using statements about respondents' health relative to the health of others as well as respondents' prognoses of their health status. These measures are established indicators of HRQOL ( 27 ) and capture key aspects of the HRQOL construct ( 9 ).

Sociodemographic characteristics included age (from the National Psychosis Registry), race, self-reported education, and employment status. Social support was assessed by marital status, whether the respondent lived alone, and whether the respondent had someone to take him or her to the doctor.

Health status was assessed with the Charlson-Deyo comorbidity index ( 28 ), body mass index (based on self-reported weight and height from the LHSV), and self-reported current smoking and alcohol consumption. In addition, we indicated whether the veteran had been exposed to toxins during military service (data from the LHSV) and how frequently the veteran exercised (data from the LHSV). Finally, we indicated the serious mental illness diagnosis: schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or schizoaffective disorder.

Health services use, which may be a marker for severity of serious mental illness and may differ between men and women, was assessed by using two variables. First, we included the frequency of recent hospitalizations (based on the National Psychosis Registry inpatient data file), an important indicator of severity of serious mental illness or comorbid conditions. Second, we included a variable indicating whether the veteran had used outpatient health services outside the VA system (based on self-reported use outside the VA; data from the LHSV). Although the vast majority of veterans receive their inpatient care in the VA, some have outside providers for outpatient services. Female veterans are more likely than males to use non-VA providers for mental health services ( 29 ).

Statistical analysis

To assess whether there were underlying clinical and demographic differences between men and women in this sample, we used tests of comparison (t test and chi square analyses) to explore gender differences across a wide range of variables.

Next, we examined the bivariate relationship between gender and our HRQOL outcomes by using t test and chi square analyses. Finally, we used linear and logistic multiple regression models to examine the effect of gender on the HRQOL measures, adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics, health status, and health services use.

All analyses described here were performed with SAS statistical software, version 9.1.

Results

The sample comprised 1,324 women (7.3%) and 16,693 men (92.7%), with a mean age of 54.3±12.2 years. Three-quarters of the sample were Caucasian (N= 13,632, or 75.7%), 8.3% (N=1,499) were Latino, 15.9% (N= 2,856) were African American, and 1.1% (N=201) were Asian. Fourteen percent (N=2,587) had not completed a high school education, 37.2% (N=6,700) were married, and 83.8% (N=15,103) were unemployed. Of the diagnoses of serious mental illness, schizophrenia was the most common (N=8,811, or 48.9%), followed by bipolar disorder (N= 7,226, or 40.1%) and schizoaffective disorder (N= 1,980, or 11.0%).

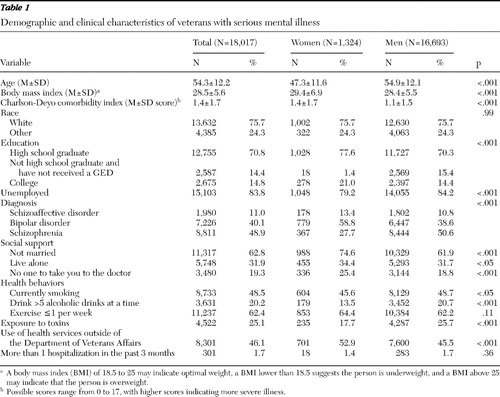

Table 1 displays the sample characteristics by gender. Compared with male respondents, females were younger, more likely to be diagnosed as having bipolar disorder, more likely to have a high school education, more likely to be employed, less likely to be married, and more likely to live alone. In addition, female respondents reported greater use of health services outside of the VA.

|

Female and male veterans with a serious mental illness also differed on several health status and health behavior measures. Women had a higher mean score on the Charlson-Deyo comorbidity index (score of 1.4 versus 1.1, p<.001), indicating a higher burden of comorbid medical illness. Women were less likely to smoke or to participate in binge drinking (more than five alcoholic drinks at a time), and they were less likely to have been exposed to toxins during military service.

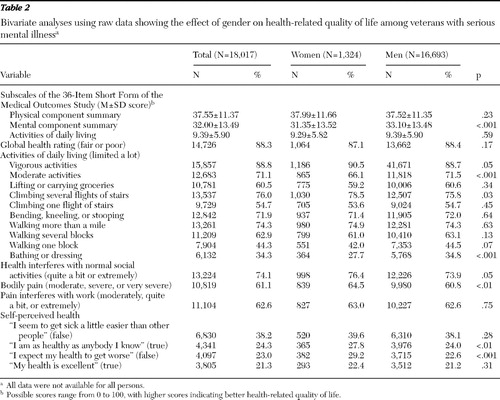

Table 2 presents the unadjusted comparison of HRQOL measures between female and male veterans with serious mental illness. Female veterans had lower mean scores on the MCS of the SF-36 (31.35 versus 33.10, p<.001), indicating worse mental health. In performing ADLs, female veterans were less likely than male veterans to report that they were "limited a lot" in moderate activities (such as moving a table, pushing a vacuum cleaner, bowling, or playing golf) and in bathing or dressing themselves, but they were more likely to say that they were limited a lot in climbing several flights of stairs. Female veterans also reported more bodily pain; compared with men, a higher proportion of women reported that their pain was moderate, severe, or very severe, compared with mild, very mild, or no pain. Despite this, female veterans had better self-perceived health.

|

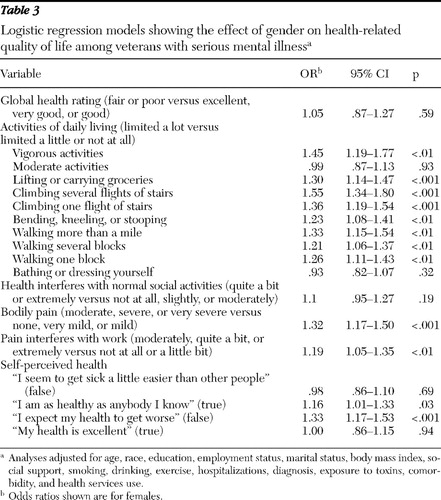

In our multivariable analyses of the effect of gender on HRQOL—where we adjusted for sociodemographic variables, health status, health behavior, and health services use—the differences between male and female veterans with serious mental illness were more pronounced. Female gender was associated with a lower score on the PCS of the SF-36 ( β =–1.18, SE=.29, p<.001), indicating worse physical health. In contrast to the unadjusted results, there was not a significant association between gender and the MCS. Female gender was also associated with a higher score on the ADL scale ( β =.81, SE=.15, p<.001), indicating greater ADL limitations. Indeed, on the individual ADL measures, there were small to moderate effects of female gender on being "limited a lot" in eight out of ten of the ADLs measured ( Table 3 ). Female veterans also fared worse in terms of bodily pain; female gender was associated with more severe pain and a higher likelihood of having pain interfere with work and usual activities ( Table 3 ).

|

Interestingly, there was a positive association between female gender and self-perceived health; women were more likely to report that they were "as healthy as anybody [they] know" and had more positive prognoses about their health—that is, they were less likely to agree with the statement "I expect my health to get worse."

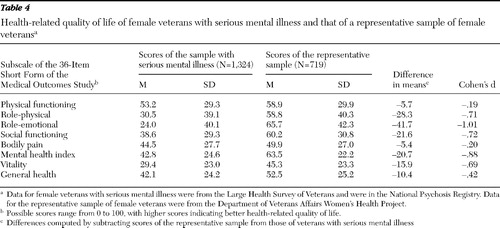

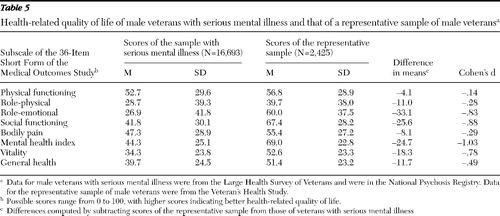

To determine the extent to which our findings of gender differences in HRQOL are unique to a population with serious mental illness, we conducted a post hoc analysis to compare our results to normative data from previously published studies. For these analyses, we used the standardized eight scales of the SF-36 as our outcome variables: physical functioning, role-physical, role-emotional, social functioning, bodily pain, the mental health index, vitality, and general health. We calculated the means and standard deviations by gender for these scales in our population. We then compared these mean scores to the published mean scores for each gender from two surveys of veterans: the VA Women's Health Project (N=719 women) ( 30 ) and the Veteran's Health Study (N=2,425 men) ( 31 ). We calculated the difference in means and estimated the effect size using Cohen's d ( 32 ). Small, medium, and large effects for Cohen's d are .20, .50, and .80, respectively ( 33 ). Tables 4 and 5 display the results of these analyses.

|

|

As might be expected, the differences between our sample and the representative veteran samples on scales related to mental health (role-emotional and the mental health index) had large effect sizes; male and female veterans in our sample had worse mental health. For women, moderate effect sizes were observed for differences in social functioning, vitality, and role-physical; women in our sample had lower mean scores on these scales. For men, moderate effect sizes were observed for differences in social functioning and vitality; men in our sample had lower scores on these scales.

Discussion

Female and male veterans with serious mental illness differed on several aspects of HRQOL. Women were more impaired than men on many ADLs, including lifting and carrying groceries, climbing stairs, and walking both short and long distances. In addition, women reported more bodily pain and were more likely to say that their pain interferes significantly with their work and daily activities. Despite this, we found that female veterans with serious mental illness had better self-perceived health than men.

HRQOL is an important outcome measure for serious mental illness. Poor HRQOL may inhibit treatment response and limit a person's ability to receive mental health treatment. Persons with serious mental illness die from medical illnesses on average 20 to 30 years younger than those without serious mental illness ( 34 ); attention to improving the HRQOL of this population may help to ameliorate these disparities and thus lengthen and improve the quality of life for these individuals. However, as our findings indicate, women and men with serious mental illness may have very different health care and life maintenance needs that could affect their recovery and long-term outcomes. Attention to improving the HRQOL of this population necessitates a gender-focused approach to maximize the benefits.

Recent studies exploring the effect of gender on serious mental illness have found significant differences between women and men in the prevalence ( 35 ), symptoms ( 36 ), course ( 37 ), and treatment response ( 38 , 39 ) of these illnesses. Our research adds to these findings to include gender differences in HRQOL for persons with serious mental illness. Taken together, it is clear that women with serious mental illness may have different treatment needs than men. In the traditional VA treatment setting, however, treatments for and research on serious mental illness have been exclusively focused on the needs of male veterans. With the advent of a rising population of female veterans, the VA has increased attention to the differing mental health needs of men and women. For example, the Palo Alto VA established a national Women's Mental Health Center in 2002, focusing exclusively on the mental health needs of female veterans. In addition, VA-sponsored research is increasingly examining gender differences in mental health services use, need for services, and outcomes. As the female veteran population continues to grow, this research is essential to ensure that adequate care is provided. It is still unclear what barriers female veterans with serious mental illness face in receiving appropriate treatment and how women and men differ in the type and frequency of mental health services they use.

Despite the large, nationally based sample, there are limitations to this study that warrant consideration. There is the potential for response bias, because individuals who were too symptomatic may not have responded to the LHSV survey. In addition, although we controlled for many variables that could confound the relationship between gender and HRQOL, there may be omitted-variable bias as a result of unmeasured gender differences. In particular, there may be a difference in the level of disability between male and female veterans that could affect HRQOL; as a result of limitations in our data, we were not able to assess this difference. Finally, the measurement of HRQOL is imperfect. The scales used in this study are measures with high internal validity, although they may not capture the full construct of HRQOL. Future research should be dedicated to improving our measurement of HRQOL; a promising collaborative research project of the National Institute of Mental Health (the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) aims to do just this ( 40 ).

Conclusions

HRQOL was found to differ for male and female veterans with serious mental illness. Women reported worse HRQOL on several domains, including ADLs and bodily pain. However, women reported better self-perceived health than men. For researchers and clinicians interested in improving the quality of life for people with serious mental illness, these findings suggest the need for attention to the needs of female veterans in particular. This is especially paramount given the increasing numbers of women in the military who will eventually be using VA services.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors acknowledge funding for this research from grant T32-MH-19986 from the National Institute of Mental Health and funding from the Health Services Research and Development division of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Wu EQ, Birnbaum HG, Shi L, et al: The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2002. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 66:1122–1129, 2005Google Scholar

2. Miller BJ, Paschall CB III, Svendsen DP: Mortality and medical comorbidity among patients with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 57:1482–1487, 2006Google Scholar

3. Folsom DP, Hawthorne W, Lindamer L, et al: Prevalence and risk factors for homelessness and utilization of mental health services among 10,340 patients with serious mental illness in a large public mental health system. American Journal of Psychiatry 162:370–376, 2005Google Scholar

4. Draine J, Salzer MS, Culhane DP, et al: Role of social disadvantage in crime, joblessness, and homelessness among persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 53:565–573, 2002Google Scholar

5. Michalak EE, Yatham LN, Kolesar S, et al: Bipolar disorder and quality of life: a patient-centered perspective. Quality of Life Research 15:25–37, 2006Google Scholar

6. Michalak EE, Yatham LN, Lam RW: Quality of life in bipolar disorder: a review of the literature. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 3:72, 2005Google Scholar

7. Hakkaart-van Roijen L, Hoeijenbos MB, Regeer EJ, et al: The societal costs and quality of life of patients suffering from bipolar disorder in the Netherlands. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 110:383–392, 2004Google Scholar

8. Arnold LM, Witzeman KA, Swank ML, et al: Health-related quality of life using the SF-36 in patients with bipolar disorder compared with patients with chronic back pain and the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders 57:235–239, 2000Google Scholar

9. Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Patrick DL: Measuring health-related quality of life. Annals of Internal Medicine 118:622–629, 1993Google Scholar

10. Bosworth HB, Siegler IC, Brummett BH, et al: The association between self-rated health and mortality in a well-characterized sample of coronary artery disease patients. Medical Care 37:1226–1236, 1999Google Scholar

11. Singh JA, Borowsky SJ, Nugent S, et al: Health-related quality of life, functional impairment, and healthcare utilization by veterans: veterans' quality of life study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 53:108–113, 2005Google Scholar

12. Yano EM, Bastian LA, Frayne SM, et al: Toward a VA Women's Health Research Agenda: setting evidence-based priorities to improve the health and health care of women veterans. Journal of General Internal Medicine 21(suppl 3):S93–S101, 2006Google Scholar

13. Blow FC, McCarthy JF, Valenstein M, et al: Care for Veterans With Psychosis in the Veterans Health Administration, FY2004, 6th Annual National Psychosis Registry Report. Ann Arbor, Mich, Serious Mental Illness Treatment Research and Evaluation Center (SMITREC), 2004Google Scholar

14. Gallicchio L, Hoffman SC, Helzlsouer KJ: The relationship between gender, social support, and health-related quality of life in a community-based study in Washington County, Maryland. Quality of Life Research 16:777–786, 2007Google Scholar

15. Linzer M, Spitzer R, Kroenke K, et al: Gender, quality of life, and mental disorders in primary care: results from the PRIME-MD 1000 study. American Journal of Medicine 101:526–533, 1996Google Scholar

16. Jorngarden A, Wettergen L, von Essen L: Measuring health-related quality of life in adolescents and young adults: Swedish normative data for the SF-36 and the HADS, and the influence of age, gender, and method of administration. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 4:91, 2006Google Scholar

17. Mrus JM, Williams PL, Tsevat J, et al: Gender differences in health-related quality of life in patients with HIV/AIDS. Quality of Life Research 14:479–491, 2005Google Scholar

18. Arrington-Sanders R, Yi MS, Tsevat J, et al: Gender differences in health-related quality of life of adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 4:5, 2006Google Scholar

19. Robb JC, Young LT, Cooke RG, et al: Gender differences in patients with bipolar disorder influence outcome in the Medical Outcomes Survey (SF-20) subscale scores. Journal of Affective Disorders 49:189–193, 1998Google Scholar

20. Chafetz L, White MC, Collins-Bride G, et al: Predictors of physical functioning among adults with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 57:225–231, 2006Google Scholar

21. Frayne SM, Parker VA, Christiansen CL, et al: Health status among 28,000 women veterans: the VA Women's Health Program Evaluation Project. Journal of General Internal Medicine 21(suppl 3):S40–S46, 2006Google Scholar

22. Blow FC, McCarthy JF, Valenstein M: Care in the VHA for Veterans With Psychosis: FY99: First Annual Report on Veterans With Psychoses. Ann Arbor, Mich, Department of Veterans Affairs, National Serious Mental Illness Treatment Research and Evaluation Center, Nov 2000Google Scholar

23. Health Status and Outcomes of Veterans. Physical and Mental Component Summary Scores Veterans SF-36:1999 Large Health Survey of Veteran Enrollees Executive Report. Washington, DC, Veterans Health Administration Office of Quality Performance, May 2000Google Scholar

24. Selim AJ, Berlowitz DR, Fincke G, et al: The health status of elderly veteran enrollees in the Veterans Health Administration. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 52:1271–1276, 2004Google Scholar

25. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): I. conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care 30:473–483, 1992Google Scholar

26. Miilunpalo S, Vuori I, Oja P, et al: Self-rated health status as a health measure: the predictive value of self-reported health status on the use of physician services and on mortality in the working-age population. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 50:517–528, 1997Google Scholar

27. McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Raczek AE: The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Medical Care 31:247–263, 1993Google Scholar

28. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA: Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 45:613–619, 1992Google Scholar

29. Hoff RA, Rosenheck RA: The use of VA and non-VA mental health services by female veterans. Medical Care 36:1524–1533, 1998Google Scholar

30. Skinner K, Sullivan LM, Tripp TJ, et al: Comparing the health status of male and female veterans who use VA health care: results from the VA Women's Health Project. Women and Health 29:17–33, 1999Google Scholar

31. Kazis LE, Ren XS, Lee A, et al: Health status in VA patients: results from the Veterans Health Study. American Journal of Medical Quality 14:28–38, 1999Google Scholar

32. Cohen J: A power primer. Psychological Bulletin 112:155–159, 1992Google Scholar

33. Krein SL, Bingham CR, McCarthy JF, et al: Diabetes treatment among VA patients with comorbid serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 57:1016–1021, 2006Google Scholar

34. Osborn DP, Levy G, Nazareth I, et al: Relative risk of cardiovascular and cancer mortality in people with severe mental illness from the United Kingdom's General Practice Research Database. Archives of General Psychiatry 64:242–249, 2007Google Scholar

35. Baldassano CF, Marangell LB, Gyulai L, et al: Gender differences in bipolar disorder: retrospective data from the first 500 STEP-BD participants. Bipolar Disorders 7:465–470, 2005Google Scholar

36. Baldassano CF: Illness course, comorbidity, gender, and suicidality in patients with bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 67(suppl 11):8–11, 2006Google Scholar

37. Usall J, Ochoa S, Araya S, et al: Gender differences and outcome in schizophrenia: a 2-year follow-up study in a large community sample. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 18:282–284, 2003Google Scholar

38. Huber TJ, Schneider U, Rollnik J: Gender differences in the effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research 120:103–105, 2003Google Scholar

39. Tamminga CA: Gender and schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 58(suppl 15):33–37, 1997Google Scholar

40. Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al: The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Medical Care 45:S3– S11, 2007Google Scholar