Unmet Needs of Families of Adults With Mental Illness and Preferences Regarding Family Services

Early studies assessing the needs of families of adults with mental illness have consistently found that families need information about their relative's illness, coping strategies, support, understanding of the illness, and assistance with problem-solving ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ). Over 30 controlled and comparative research trials have found that family psychoeducation models that last nine months and provide information about mental illness, emotional support, problem-solving skills, and crisis intervention reduce relapse and rehospitalization for persons with mental illness and improve well-being for their family member ( 7 ). These interventions differ in the format, combination of educational and support services, and timing in which the intervention is delivered. The significant evidence for the effectiveness of family psychoeducation models has resulted in their designation as an evidence-based practice ( 8 , 9 , 10 ).

Identification of family psychoeducation as an evidence-based practice has led to numerous dissemination efforts that have had limited success in reaching large numbers of consumers. The eight-state project to test the effectiveness of toolkits for dissemination of evidence-based practices resulted in relatively few consumers receiving family psychoeducation (Marshall T, Whitley R, unpublished manuscript, 2008). New York State's effort to implement family psychoeducation programs at 35 sites was recently replaced with an effort to promote a family consultation model ( 11 ), in part because of low penetration of the program and the perception that family psychoeducation was not effectively meeting the needs of most families in the public system.

Although many system and provider barriers to family psychoeducation have been explored ( 12 ), little is known about family- and consumer-related barriers to family psychoeducation. One potential reason for the low participation in family psychoeducation may be that services do not appropriately target the differing needs and preferences of family members and consumers ( 13 , 14 , 15 ). Limited research describes family and consumer characteristics that influence the types of information and support services families want. Family member characteristics—such as phase of life or age ( 13 , 16 , 17 , 18 ), gender or relationship to the ill relative ( 19 , 20 ), ethnicity ( 21 , 22 ), and experiences of stigma ( 5 , 12 , 23 , 24 )—and consumer characteristics—such as contact with family ( 6 , 22 ), diagnosis ( 25 ), duration of mental illness ( 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ), and severity of mental illness ( 30 )—may influence family need.

The reasons for the limited penetration of family psychoeducation require further understanding of family preferences and need for services. We thus aimed to examine the types of support and education that families of adults with mental illness need and have received, to examine whether specific family and consumer characteristics are associated with differences in families' perceptions of need, and to explore families' preferences for how information and support services should be offered.

Methods

Participants and procedures

We employed a cross-sectional survey design targeting the family members of adults with mental illness. All procedures were approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Maryland and the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. We attempted to recruit family respondents through two sources: local mental health authorities and the Maryland chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI Maryland). All family respondents were English speaking and able to provide informed consent for study participation. Surveys were completed between June 2004 and May 2005.

Two state hospitals, three community outpatient mental health centers, and one community inpatient facility were asked to provide a list of the names, telephone numbers, and addresses of all adult clients (age 18 or older) diagnosed as having a serious mental illness. This category typically includes individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, and chronic or persistent major depression. Lists from outpatient facilities included current clients, and lists from inpatient facilities reflected clients discharged in the past three months.

Consumers of mental health services identified on the provider lists received letters describing the study and informing them that a researcher would contact them. Consumers unwilling to be contacted were asked to inform their mental health provider or the researcher directly and were removed from the list. We then attempted to contact the remaining consumers by telephone. We provided them with a description of the study and asked for their permission to contact a family member of their choice. With such permission, we attempted to contact family members and sought their consent for study participation. Family members who agreed to participate were mailed an introductory letter, a self-administered survey, two copies of the consent form (one to be signed and returned to the researcher), and a postage-paid return envelope. In an effort to increase the response rate ( 31 ), family members who did not return the survey after three weeks were sent reminder postcards and a final reminder call was made one week before the survey deadline.

Family members were also recruited for the study through NAMI Maryland. An introductory letter, consent forms, a postage-paid return envelope, and the survey instrument were sent to all current NAMI Maryland members by NAMI staff. Procedures identical to those described above were used to contact family members who had not returned the survey.

Participating community mental health facilities identified a total of 481 consumers. Of those, 70 (15%) gave permission to contact their family member, 113 (23%) refused permission, and 298 (62%) were unreachable (that is, wrong phone number was listed, consumer had moved, or consumer was hospitalized). Of the 70 family members identified as potential respondents, 33 (47%) consented, 19 (27%) refused, 18 (26%) were unreachable because of inadequate or inaccurate contact information, and 16 (23%) returned the survey. This response rate was lower than other studies using similar sampling techniques ( 6 , 32 , 33 ). A total of 962 eligible family members were included in the NAMI Maryland database. Of the 962, a total of 316 (33%) returned the survey. This response rate is methodologically similar to other studies ( 34 ).

Because of the low number of respondents recruited through mental health facilities, only information collected through the NAMI sample is reported here. Respondents were included in the analysis if they reported having a relative who was diagnosed as having any mental illness (that is, schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, major depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder or any other anxiety disorder, borderline personality disorder, or a substance use disorder). Data from eight respondents were excluded because they did not meet inclusion criteria (six because the respondents' relative was younger than 18 years and two because the respondents' relative was not clearly diagnosed as having a mental illness).

Survey

Family information and support needs. We assessed four areas of family information and support needs: need for information about the relative's mental health, need for information about negotiating for services, need for information about community resources, and need for skills for assisting a relative with mental illness. The 16 items we used to measure these need categories were adapted from the Yale-Northeast Program Evaluation Center Family Assessment of Needs for Services (FANS) ( 35 ) (items listed in Table 3). We identified four possible conditions: unmet need because the information was never received, unmet need because family members have not received enough information, no current need because family members have received enough information, and never a need for the information. These four categories were later collapsed into two categories that reflect unmet need (current need because information was never received or they did not receive enough information) and receipt of information (any prior receipt of information). Number of unmet needs was tallied by the four areas of family information and support described above and in an overall score. (Possible number of total needs range from 0 to 16.) Additionally, respondents were asked to identify which information was most important to them and the preferred mode and method (where, how, when, and by whom) of receiving that information.

Family member characteristics. Characteristics believed to affect family information and support needs were assessed, including age, ethnicity, gender, employment status, level of education, income, relationship to the ill relative, and contact with the ill relative (whether the ill relative lived with the family, whether the family member was the primary caregiver, and frequency of contact with the ill relative).

Ill relative characteristics. Characteristics of the ill relative believed to affect family information and support needs were assessed, including age, gender, employment status, diagnosis, length of time with the illness, onset of the illness, mastery or control over the illness, and severity of the illness. Onset of the illness was measured by asking respondents whether their relative's mental health problems appeared suddenly. Mastery or control over the illness was measured by asking whether the respondent's relative was currently receiving treatment or taking medication and whether the respondent perceived the illness as being short term, episodic, chronic with periodic relapses, or a chronic illness that will never improve. Severity of the illness was measured by asking respondents whether their relatives had been hospitalized for their mental health problem or had attempted to harm themselves or someone else in the past year.

Family perceptions of stigma. Two items adapted from the Experience of Caregiving Inventory ( 36 ) were included to measure the family members' perceptions of stigma. Respondents were asked whether they felt stigmatized by people in the community or the mental health system because of their relative's mental illness and whether stigma prevented them from seeking services for themselves or their family member.

Participation in family services. Four items were included to assess respondents' knowledge of and participation in two family services: family psychoeducation and NAMI's Family-to-Family Education Program. The Family-to-Family Education Program is a 12-week course taught by trained family members for family caregivers of individuals with mental illness.

Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize family education and support needs, characteristics of the respondent and the ill relative, and the respondent's perception of the relative's mental illness. We excluded the item "support groups for families of relatives with mental illness" because we were examining a NAMI sample. Frequencies were also used to summarize the most important needs identified by family members (reflecting needs identified as the most important and the second most important) and their preferences for how information and support services should be offered.

We assessed the bivariate relationships between number of unmet needs and characteristics of the family member, characteristics of the ill relative, and family perceptions of stigma by using Pearson's product-moment correlation (continuous variables), point-biserial correlations (dichotomous variables), and one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) (categorical variables). Given the relationship between stigma and unmet need, bivariate analyses (for example, Pearson's product-moment correlations, point-biserial correlations, and one-way ANOVAs) were conducted to assess relationships between the family member's perception of stigma, the family member's characteristics, and the ill relative's characteristics. Variables that were significantly associated with stigma were included in a multivariate analysis to determine their relative unique contributions to unmet needs.

Results

Family member and ill relative characteristics

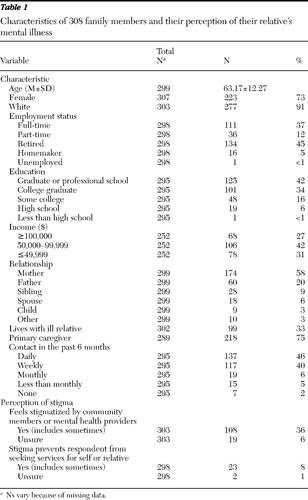

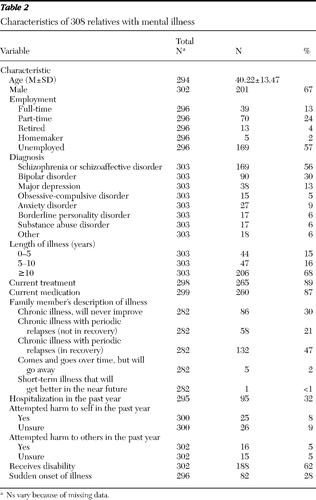

Table 1 shows the characteristics of family respondents, their perceptions of their relative's illness, and their experience of stigma. A total of 108 (36%) family respondents reported feeling stigmatized by people in their community or the mental health system because of their relative's mental illness. However, only 23 (8%) reported that stigma prevented them from seeking mental health services. (All data were not available for all respondents.) Table 2 highlights demographic and clinical characteristics of the ill relatives.

|

|

Participation in family services

A majority of family respondents had knowledge of (N=265, or 89%) or had participated in (N=167, or 56%) the Family-to-Family Education Program provided through NAMI. In contrast, only 50 (17%) had heard of family psychoeducation and only 13 (4%) had participated in a family psychoeducation program.

Family information and support needs

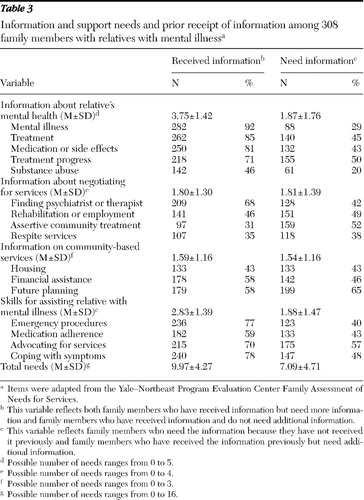

Family respondents reported a substantial number of unmet needs. On average, family respondents indicated the need for approximately half of the topics presented (mean±SD of 7.09±4.71 topics; possible number ranges from 0 to 16). More than half of family respondents reported needing information on their relative's treatment progress, assertive community treatment, future planning for care of their ill relative, and advocating for services for their ill relative ( Table 3 ). No individual need or specific area of need emerged as most important.

|

Although almost all family respondents reported prior receipt of information (N=294, or 96%), a substantial number indicated continued need for that same information (N=234, or 79%). Specifically, family respondents reported wanting additional information regarding planning for their ill relative's future (109 of 179 respondents, or 61%), advocating for better services or treatment for their relative (119 of 215 respondents, or 55%), and rehabilitation or housing services (69 of 141 respondents, or 49%).

Preferred modes and methods for receiving information

A majority of family respondents preferred that information and support be provided by a mental health professional (N=195, or 63%) and that this information would be delivered in person (N=88, or 29%) or in writing (N=66, or 21%). Most family respondents preferred to receive this information on an as-needed basis (N=180, or 58%), in a mental health clinic or hospital (N=90, or 29%), or in their own home (N=72, or 23%).

Relationship between characteristics and unmet needs

Older family respondents reported fewer unmet needs, and more specifically, fewer unmet needs for information concerning negotiating for services and skills to assist their ill relative. Also, family members who were retired reported fewer needs (6.34±4.47 needs) than those who worked full-time (7.85±4.70 needs) or part-time (7.85±4.67 needs) (F=2.86, df=3 and 293, p<.05). Unmet needs did not differ on the basis of family respondents' education, income, or relationship to their ill relative.

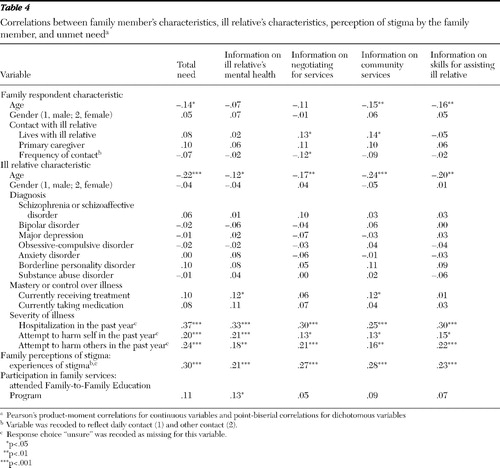

Family respondents who reported that their ill relative had a more recently occurring or disabling form of mental illness had greater unmet needs ( Table 4 ). Family respondents with relatives who were younger, were unemployed, or had been hospitalized or had attempted to harm themselves or others in the past year reported greater unmet needs than their comparison groups. Family respondents with relatives with a length of illness of ten or more years reported significantly fewer unmet needs (6.43±4.45 needs) than those with relatives with a shorter length of illness (zero to five years: 8.30±5.16 needs; five to ten years: 9.22±4.55 needs) (F=8.73, df=2 and 294, p<.001). Living with an ill relative was associated with a greater need for information in specific areas (for example, negotiating services and community resources) but not greater unmet needs, overall. Family members who perceived a relative's condition as being chronic and in recovery reported greater needs (8.47±4.60 needs) than those who viewed the condition as being in recovery (6.64±4.70 needs) or as a condition that never improves (6.87±4.50 needs) (F=3.30, df=2 and 273, p<.05) (the other two response options were excluded from the analyses because of the small subsample). Unmet needs were largely unrelated to the family respondent's perception of the ill relative's mastery or control of illness, the ill relative's diagnosis, and the gender of the family respondent.

|

Family perceptions of stigma and relation to unmet needs

Family respondents who reported feeling stigmatized by people in their community or the mental health system because of their relative's mental illness were more likely to have greater needs, both overall and within each of the four areas of family information and support needs. However, feelings of stigma were not associated with receipt of services.

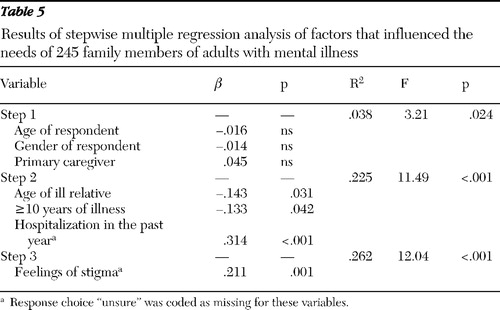

Multivariate analyses

Feelings of stigma were strongly associated with unmet needs even after the analysis controlled for family characteristics (for example, age, gender, and caregiver status) and consumer characteristics (for example, age, years of illness, and recent hospitalization) ( Table 5 ). However, demographic characteristics of the ill relative were also uniquely predictive of unmet needs. When other factors were controlled for, having a relative who was younger, who had a shorter length of illness, or who had a hospitalization in the past year was associated with greater unmet needs.

|

Discussion

This study provides an overview of the information needs of the families of individuals with mental illness and preferences for how these needs should be addressed. Our results confirm the substantial unmet need among family members of adults with mental illness found in earlier studies ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ). Our findings extend previous work by highlighting the presence of ongoing need, despite prior receipt of the information. Given that over half of our family respondents completed the NAMI Family-to-Family Education Program and all were involved in NAMI support groups, the extent of this need is particularly noteworthy. These results suggest that family needs cannot be adequately addressed by simply providing information once, but rather, ongoing provision of information and support is required.

Ongoing need may be due, in part, to the diverse and changing needs of families. Need varied considerably among families, often dependent on the current family situation and psychiatric status of the ill relative. Family members of consumers experiencing an emergence or reemergence of symptoms (for example, younger consumers and individuals recently hospitalized) require more information and support. These families might benefit from a more structured behavioral program, like family psychoeducation ( 37 , 38 ). In contrast, families of individuals with a longer history of illness and of those who have made significant steps toward recovery have already gained skills and knowledge to assist their relative. These families, as well as older parents and primary caregivers, often report the need for more targeted information, such as planning for the future care of an ill relative in their absence ( 39 , 40 ). Thus different needs that occur during various stages of illness and recovery argue for a more tailored approach to family services.

Interestingly, we found that family members who felt stigmatized by mental health providers or the community experienced greater need in all areas. These cross-sectional data do not permit inferences regarding cause and effect. It is possible that the experience of stigma may lead to greater educational need, either through the damaging effects of stigma or because the types of services that people receive do not effectively neutralize the impact of stigma. On the other hand, greater need may create a greater vulnerability and perhaps increased sensitivity to stigma. Regardless, these findings suggest that mental health providers should explore perceptions of stigma with families to whom they are providing services.

Consistent with reports of family-related barriers ( 12 ), we found that family members of adults with mental illness have limited knowledge of family psychoeducation. The awareness of the Family-to-Family Education Program is likely due to our NAMI sample. Limited knowledge of family psychoeducation in this group may reflect a lack of available family psychoeducation programs, a lack of awareness of the existence of these programs, or both. Although the reason for limited knowledge of family psychoeducation is unclear, these results confirm previous findings that knowledge of and participation in this program remains minimal despite significant implementation efforts.

Families prefer greater flexibility in how family services are provided. Both the Family-to-Family Education Program and family psychoeducation programs are fairly structured in format and content, with family members meeting on a weekly basis for 12 weeks for the Family-to-Family Education Program or nine months to a year or more for a family psychoeducation program. However, families indicated a preference in receiving information on an as-needed basis, rather than in regularly scheduled meetings. Families also preferred receiving this information from a mental health provider, preferably their relative's mental health provider. In addition, family members expressed interest in services that extend beyond the mental health clinic or hospital to include more community and home care.

This study has a significant limitation in that it includes only the perspectives of NAMI Maryland families. Although this sample is important to understand, it is not representative of all consumers or of all consumers receiving services in Maryland ( 41 ). Family members in our sample were primarily Caucasian, female, and educated and had a higher level of income—factors shown to influence family needs.

Failure to recruit a sample from community treatment facilities is an important outcome and requires discussion. Despite attempts to recruit family members from a variety of settings, recruiting families through community treatment facilities proved difficult. Inadequate contact information was available for almost two-thirds of eligible consumers and approximately one-quarter of identified family members. In addition, a substantial number of consumers and families for whom contact information was available refused to participate. Refusals may reflect both consumer-level barriers (for example, concerns about family burden, confidentiality issues, and stigma) and family-level barriers (for example, time constraints, stigma, and caregiver burden), which may be more pervasive among consumers and families less familiar with family services ( 42 ).

Legal and ethical concerns on the part of providers and service systems (that is, concerns regarding patient and family confidentiality, whether the study would violate the procedures of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, and whether clients were too vulnerable to participate in the study) may also serve to impede recruitment in community settings. In fact, two of the community inpatient facilities identified by the mental health board for recruitment in this study refused to provide lists of eligible clients, citing concerns regarding patient confidentiality. Moreover, in many community mental health settings, research has rarely been conducted. Thus lack of prior exposure to or involvement in research studies and limited familiarity with research procedures may serve to intensify provider concerns about perceived legal or ethical issues associated with recruitment and participation in research studies. Our failure to recruit a community sample despite considerable planning and effort leaves a remaining challenge for service planners.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, our results provide important information concerning the ongoing needs of families of individuals with mental illness. Furthermore, they suggest that the content and structure of these services should be tailored to the individual needs and preferences of each family. Continued efforts should be made to better understand and address both consumer and family member service needs and potential barriers to participation in family services.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This project was supported by grant P50-MH-43703 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Donald Steinwachs, Ph.D. (principal investigator). Support for the preparation of this article was provided by the Veterans Integrated Service Network 5, Mental Illness, Research, Education and Clinical Center. The authors thank the Serious Mental Illness Center, the Maryland Mental Hygiene Administration, the Maryland Chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), and Abigail Graf and Laura Lee Hall, Ph.D., from the national offices of NAMI for their assistance with this project.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Hatfield AB: Psychological costs of schizophrenia to the family. Social Work 23:355– 359, 1978Google Scholar

2. Hatfield A: What families want of family therapists, in Family Therapy in Schizophrenia. Edited by McFarlane W. New York, Guilford, 1983Google Scholar

3. Johnson D: The needs of the chronically mentally ill: as seen by the consumer, in The Chronically Mentally Ill: Research and Services. Edited by Mirabi M. New York, Spectrum, 1984Google Scholar

4. Lefley HP: Behavior manifestations of mental illness, in Families of the Mentally Ill: Meeting the Challenges: New Directions for Mental Health Services. Edited by Hatfield AB. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1987Google Scholar

5. Lefley H: Family burden and family stigma in major mental illness. American Psychologist 44:556–560, 1989Google Scholar

6. Winefield H, Harvey E: Needs of family caregivers in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 20:557–566, 1994Google Scholar

7. McFarlane WR, Dixon L, Lukens E, et al: Family psychoeducation and schizophrenia: a review of the literature. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 29:223–245, 2003Google Scholar

8. Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders: Compendium 2006. Arlington, Va, American Psychiatric Association, 2006Google Scholar

9. Frances A, Docherty JP, Kahn DA: The Expert Consensus Guidelines Series: treatment of schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57:1–88, 1996Google Scholar

10. Lehman AF, Kreyenbuhl J, Buchanan RW, et al: The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2003. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:193–217, 2004Google Scholar

11. Solomon P, Marshall T, Mannion E, et al: Social workers as consumer and family consultants, in Social Work Practice in Mental Health. Edited by Bentley K. Pacific Grove, Calif, Brookes/Cole, 2002Google Scholar

12. Dixon L, McFarlane WR, Lefley H, et al: Evidence-based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 52:903–910, 2001Google Scholar

13. Cook JA, Pickett SA, Cohler BJ: Families of adults with severe mental illness—the next generation of research: introduction. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 67:172–176, 1997Google Scholar

14. Dixon L, Adams C, Lucksted A: Update on family psychoeducation for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:5–20, 2000Google Scholar

15. Hatfield AB, Coursey R, Slaughter J: Family responses to behavior manifestations of mental illness. Innovations and Research 3:41–49, 1994Google Scholar

16. Cook JA, Lefley HP, Pickett SA, et al: Age and family burden among parents of offspring with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 64:435–447, 1994Google Scholar

17. Hatfield A: Families of adults with severe mental illness: new directions in research. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 67:254–260, 1997Google Scholar

18. Smith GC, Hatfield AB, Miller DC: Planning by older mothers for the future care of offspring with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 51:1162–1166, 2000Google Scholar

19. Johnson E: Differences among families coping with serious mental illness: a qualitative analysis. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 70:126–134, 2000Google Scholar

20. Wintersteen R, Rasmussen K: Fathers of persons with mental illness: a preliminary study of coping capacity and service needs. Community Mental Health Journal 33:401– 413, 1997Google Scholar

21. Guarnaccia PJ, Parra P: Ethnicity, social status, and families' experiences of caring for a mentally ill family member. Community Mental Health Journal 32:243–260, 1996Google Scholar

22. Horwitz A, Reinhard S: Ethnic differences in caregiving duties and burdens among parents and siblings of persons with severe mental illnesses. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36:138–150, 1995Google Scholar

23. Phelan JC, Bromet EJ, Link BG: Psychiatric illness and family stigma. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:115–126, 1998Google Scholar

24. Wahl O, Harman CR: Family views of stigma. Schizophrenia Bulletin 15:131–139, 1989Google Scholar

25. Thompson R, Weisberg S: Families as educational consumers: what do they want? What do they receive? Health and Social Work 15:221–227, 1990Google Scholar

26. Gonzales S, Steinglass P, Reiss D: Putting the illness in its place: discussion group for families with chronic medical illnesses. Family Processes 28:69–87, 1989Google Scholar

27. Linszen DH, Dingemans P, Van der Does JW, et al: Treatment, expressed emotion, and relapse in recent onset schizophrenic disorders. Psychological Medicine 26:333–342, 1996Google Scholar

28. Nugter A, Dingemans P, Van der Does JW, et al: Family treatment, expressed emotion and relapse in recent onset schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research 72:23–31, 1997Google Scholar

29. Solomon PJ, Draine J, Mannion E, et al: Impact of brief family psychoeducation on self-efficacy. Schizophrenia Bulletin 22:41–50, 1996Google Scholar

30. Rund BR, Moe L, Sollien T, et al: The psychosis project: outcome and cost-effectiveness of a psychoeducational treatment program for schizophrenic adolescents. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 89:211–218, 1994Google Scholar

31. James JM, Bolstein R: The effect of monetary incentives and follow-up mailings on the response rate and response quality in mail surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly 54:346– 361, 1990Google Scholar

32. Greenberg JS, Kim HW, Greenly JR: Factors associated with subjective burden in siblings of adults with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 67:231–241, 1997Google Scholar

33. Marshall T, Solomon P: Confidentiality intervention: effects on provider-consumer-family collaboration. Research on Social Work Practice 14:3–13, 2004Google Scholar

34. Looper K, Fielding A, Latimer E, et al: Improving access to family support organizations: a member survey of the AMI–Quebec Alliance for the Mentally Ill. Psychiatric Services 49:1491–1492, 1998Google Scholar

35. Perlick D, Wolff N, Miklowitz DJ, et al: Development of an integrated model of family burden. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 6(suppl):37, 2003Google Scholar

36. Szmukler GI, Burgess P, Herman H, et al: Caring for relatives with serious mental illness—the development of the Experience of Caregiving Inventory. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 31:134–148, 1996Google Scholar

37. Glynn SM, Cohen AN, Dixon LB, et al: The potential impact of the recovery movement on family interventions for schizophrenia: opportunities and obstacles. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32:451–463, 2006Google Scholar

38. McFarlane WR, Luckens E, Link B, et al: Multiple-family groups and psychoeducation in the treatment of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:679–687, 1995Google Scholar

39. Hatfield AB, Lefley HP: Helping elderly caregivers plan for the future care of a relative with mental illness. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 24:103–107, 2000Google Scholar

40. Lefley HP, Hatfield AB: Helping parental caregivers and mental health consumers cope with parental aging and loss. Psychiatric Services 50:369–375, 1999Google Scholar

41. Leighniger RD, Speier AH, Mayeux D: How representative is NAMI? Demographic comparisons of a national NAMI sample with members and non-members of Louisiana mental health support groups. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 19:71–73, 1996Google Scholar

42. Murray-Swank A, Glynn S, Cohen A, et al: Family contact, experience of family relationships, and views about family involvement in treatment among VA consumers with serious mental illness. Journal of Rehabilitation, Research, and Development 44:801–812, 2007Google Scholar