Antipsychotic Polypharmacy Trends Among Medi-Cal Beneficiaries With Schizophrenia in San Diego County, 1999–2004

Over the past ten years, the treatment of schizophrenia and related disorders has seen a marked shift from the use of first-generation antipsychotic medications to the use of second-generation antipsychotics ( 1 ). Accompanying the rise in prescribing of second-generation antipsychotics has been an increase in the practice of prescribing multiple second-generation antipsychotics, also known as second-generation antipsychotic polypharmacy ( 2 ). Prevalence rates of polypharmacy in the treatment of patients with schizophrenia have been reported to range from 2% to 17% in the outpatient setting ( 3 , 4 ). Surveyors of clinicians' reasons for antipsychotic polypharmacy have found their primary reasons to include the treatment of persistent positive symptoms, physicians' doubts regarding the validity of evidence-based algorithms, and nurses' requests for increasing the dosage or adding additional drugs ( 5 ).

Complicating the use of second-generation antipsychotic polypharmacy is a lack of controlled trials on the practice. Recent trials have highlighted inherent safety and efficacy limitations of second-generation antipsychotic monotherapy, and results reported in polypharmacy trials involving first-generation antipsychotics have been mixed ( 6 ). Additional concerns associated with antipsychotic polypharmacy include possible adverse effects ( 7 ), excessive mortality ( 8 ), and excessive costs ( 9 ). A study of inpatients with psychotic disorders found that treatment with multiple antipsychotics was associated with higher total antipsychotic dose, greater adverse events, and longer inpatient stays, but without any apparent clinical benefit ( 7 ).

We examined antipsychotic prescribing in San Diego County, California, between 1999 and 2004. Second-generation antipsychotic polypharmacy was investigated along with inpatient admissions and antipsychotic pharmaceutical costs. Trends and potential relationships during the six-year study period are described.

Methods

Data from San Diego County's Adult and Older Adult Mental Health Services encounter-based management information system were merged with data from California's Department of Health Services to identify Medi-Cal (California's Medicaid program) beneficiaries with schizophrenia who were receiving psychiatric services and who filled prescriptions for oral antipsychotic medications between 1999 and 2004. We had used these linked-database methods previously to examine adherence to treatment with antipsychotic medications ( 10 ).

Consistent with our earlier research, we classified each prescription fill for an oral antipsychotic into one of four mutually exclusive categories: first-generation antipsychotic medications only, single second-generation medication, single second-generation medication in addition to first-generation medications, and multiple second-generation medications. Second-generation antipsychotic polypharmacy was defined as receiving multiple second-generation medications. Using previously published methods ( 10 ), we analyzed the days' supply of each antipsychotic prescription and then assigned each person to one of the four medication categories for each month in which they were enrolled in Medi-Cal and had medication available. We calculated days' supply for each medication type for each day during the study period. Only the medication with the greatest days' supply was used to calculate remaining days' supply when multiple medications were filled on a single day. We capped total days' supply on any given fill date at 300 days in order to limit the influence of excessive filling. Antipsychotic pharmacy was assigned hierarchically by month, in reverse order as described above. For example, a client who had a 15-day supply of a single second-generation medication carried over from a previous month but who filled a prescription for second-generation polypharmacy (defined by filling prescriptions for two or more different second-generation medications on the same day) would be assigned to second-generation polypharmacy for the month of the prescription fill. This client also would be assigned to second-generation polypharmacy in the following month if there was a sufficient days' supply to carry over—for example, if the client filled a 30-day prescription midmonth. Because quetiapine is commonly used as a sleeping aid, we removed quetiapine from this classification when prescribed at a low daily dose (200 mg or less) in conjunction with another antipsychotic.

For each month that a client was enrolled in Medi-Cal with a positive medication supply, we indicated the type of antipsychotic pharmacy and whether the client was admitted to an inpatient or crisis residential facility. We also calculated the duration of second-generation antipsychotic polypharmacy for a subset of persons receiving second-generation polypharmacy in a year in which they were continuously enrolled in Medi-Cal. Antipsychotic medication costs were evaluated in the full sample. Monthly amounts paid by Medi-Cal for antipsychotics were annualized (by multiplying by 12) and were adjusted to 2004 dollars with the pharmaceutical component of the consumer price index. Logistic regression was used to test for the significance of time trends in pharmacotherapy and inpatient admissions (analyzed at the person-month) and duration of second-generation polypharmacy (analyzed at the person-year). We evaluated trends in annualized costs at the person-year, using two-part models with a first-stage logistic regression and second-stage gamma regression with a log-link function.

Results

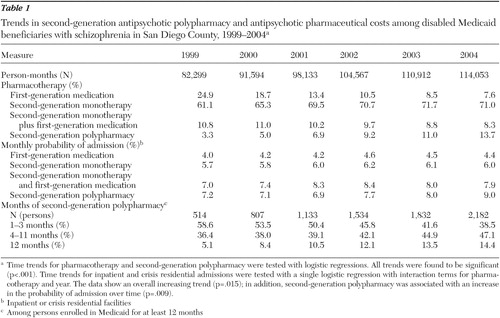

We identified 15,962 unique Medi-Cal beneficiaries with schizophrenia who filled prescriptions for antipsychotic medications between 1999 and 2004. The average monthly prevalence of second-generation polypharmacy increased from 3.3% in 1999 to 13.7% in 2004 (p<.001) ( Table 1 ). Among those receiving second-generation polypharmacy, the average monthly percentage of patients admitted to an inpatient or crisis residential facility increased from 7.2% in 1999 to 9.0% in 2004 (p=.009).

|

We identified 3,828 unique beneficiaries who filled at least one prescription for second-generation antipsychotic polypharmacy and who were continuously enrolled in Medi-Cal during a year in the period 1999–2004. Among those receiving second-generation polypharmacy and continuously enrolled, the percentage receiving continuous second-generation polypharmacy increased from 5.1% in 1999 to 14.4% in 2004 (p<.001).

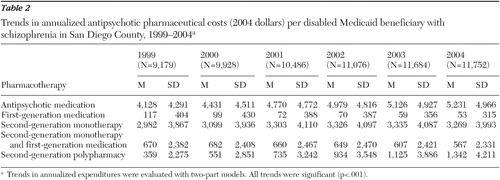

Among the full sample of 15,962 beneficiaries, the annualized antipsychotic medication costs per beneficiary increased 27%, from $4,128 in 1999 to $5,231 in 2004 (p<.001) ( Table 2 ). This increase in costs was largely the result of a $983 increase in annual costs of second-generation antipsychotic polypharmacy (p<.001).

|

Discussion and conclusions

Substantial increases in the prevalence of second-generation antipsychotic polypharmacy were found among Medi-Cal beneficiaries with schizophrenia in San Diego County between 1999 and 2004. These trends were accompanied by a 27% increase in antipsychotic medication costs that were driven primarily by a 274% increase in expenditures involving second-generation antipsychotic polypharmacy. Although the overall hospitalization rate increased from 1999 to 2004, the rate among those receiving second-generation polypharmacy increased significantly beyond this trend, rising 25% and resulting in an increase from 7.2% in 1999 to 9.0% in 2004. It is impossible to determine whether the increase in second-generation polypharmacy was causally related to increasing inpatient admissions. However, these data cast doubt on the prospect that second-generation polypharmacy improves psychological functioning sufficiently to improve the residential stability of patients.

Our findings are consistent with results from related studies. Ganguly and associates ( 4 ) found persistent use of second-generation antipsychotic polypharmacy among 5.5% of Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia in California and Georgia between 1998 and 2000. Our study considered a longer time period and found an almost twofold increase in second-generation polypharmacy in California since 2000. Kreyenbuhl and associates ( 3 ) studied long-term antipsychotic polypharmacy among Department of Veterans Affairs patients with schizophrenia by comparing time-based (30, 60, and 90 days) and cross-sectional definitions of polypharmacy. They found that the prevalence of antipsychotic polypharmacy declined substantially as definitions requiring longer periods of prescription were applied (approximately 50% from 30 to 90 days) and that cross-sectional definitions yielded different samples than their preferred time-based definitions. We found similar declines in polypharmacy during the first 90 days. We also documented a substantial increase in long-term polypharmacy over the study period. Predictors of continuing versus discontinuing second-generation antipsychotic polypharmacy warrant further investigation.

This study has several limitations. The use of an administrative claims database such as Medicaid might involve coding biases, might be influenced by reimbursement issues, and did not include some important clinical measures, such as psychopathology. Although Adult and Older Adult Mental Health Services has issued medication guidelines to county providers, the prescribing practices in this study might be more reflective of individual providers' modes or styles of prescribing, which could be influenced by the relatively open Medi-Cal formulary. Nonetheless, we have used a Medicaid database that involved a sizeable number of patients from a large, representative county in the United States.

Despite these limitations, we believe that these findings are both important and timely. California's Medicaid program has been facing large increases in costs per beneficiary, largely resulting from increases in pharmacy expenditures among elderly beneficiaries and those with disabilities. Annual expenditures on antipsychotic medications saw the largest gains of any therapeutic class, increasing from $250 million in 1999 to $719 million in 2004. Yet studies have shown that the increased use of second-generation antipsychotics in Medi-Cal has not been accompanied by improved adherence to medications or reductions in psychiatric admissions ( 10 ). The combined expense and lack of an evidence base for second-generation polypharmacy begs for additional research to examine its cost-effectiveness. Concern about the rising costs of antipsychotics among administrators of state Medicaid programs and benefits managers of pharmaceutical insurance plans may lead to increased scrutiny of second-generation polypharmacy prescribing that if left unchanged may lead to administrative efforts to cut costs and to dictate practice.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Financial support was provided by grants P30-MH-066248 and K23-MH-067895 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and by the Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors gratefully acknowledge the County of San Diego Health and Human Services Agency Adult and Older Adult Mental Health Services for access to the management information systems.

AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, and Janssen donate antipsychotic medications for Dr. Jeste's research funded by NIMH. Dr. Jeste is a consultant for Otsuka, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Solvay, and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals. The other authors report no competing interests.

1. Hermann RC, Yang D, Ettner SL, et al: Prescription of antipsychotic drugs by office-based physicians in the United States, 1989–1997. Psychiatric Services 53:425–430, 2002Google Scholar

2. Wang PS, West JC, Tanielian T, et al: Recent patterns and predictors of antipsychotic medication regimens used to treat schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:451–457, 2000Google Scholar

3. Kreyenbuhl J, Valenstein M, McCarthy JF, et al: Long-term combination antipsychotic treatment in VA patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 84:90–99, 2006Google Scholar

4. Ganguly R, Kotzan JA, Miller LS, et al: Prevalence, trends, and factors associated with antipsychotic polypharmacy among Medicaid-eligible schizophrenia patients, 1998–2000. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65:1377–1388, 2004Google Scholar

5. Ito H, Koyama A, Higuchi T: Polypharmacy and excessive dosing: psychiatrists' perceptions of antipsychotic drug prescription. British Journal of Psychiatry 187:243–247, 2005Google Scholar

6. Honer WG, Thornton AE, Chen EY, et al: Clozapine alone versus clozapine and risperidone with refractory schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine 354:472–482, 2006Google Scholar

7. Centorrino F, Goren JL, Hennen J, et al: Multiple versus single antipsychotic agents for hospitalized psychiatric patients: case-control study of risks versus benefits. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:700–706, 2004Google Scholar

8. Joukamaa M, Heliovaara M, Knekt P, et al: Schizophrenia, neuroleptic medication and mortality. British Journal of Psychiatry 188:122–127, 2006Google Scholar

9. Clark RE, Bartels SJ, Mellman TA, et al: Recent trends in antipsychotic combination therapy of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: implications for state mental health policy. Schizophrenia Bulletin 28:75–84, 2002Google Scholar

10. Gilmer TP, Dolder CR, Lacro JP, et al: Adherence to treatment with antipsychotic medication and health care costs among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:692–699, 2004Google Scholar