Use of Qualitative Methods to Explore the Quality-of-Life Construct From a Consumer Perspective

The evaluation of quality of life for individuals diagnosed as having severe and persistent mental illness has been an area of great interest in the mental health field for the past two decades. The increasing need to demonstrate to funders that services provided to these individuals are making a difference has forced the mental health field to develop and use various outcome measures in order to assess impact on areas such as quality of life. Several issues related to the evaluation of quality of life continue to be debated in the literature ( 1 ). Perhaps the most disconcerting is the lack of consensus regarding the definition of quality of life. Clearly we do not fully understand this complex construct.

Defining quality of life is not an easy matter ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ). As Awad ( 2 ) noted, quality of life is "deceptively simple and easy to understand yet complex and frequently elusive to define; it can mean different things to different people." Farquhar ( 3 ) further emphasized that "the term 'quality of life' is in vogue; it has become popularized, even clichéd…. Definitions of quality of life are as numerous and inconsistent as the methods of assessing it."

Several authors argue that quality of life has a major subjective element and can be assessed only by self-report ( 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ). Attempts to explore quality of life from the perspective of people with mental illness are scarce ( 7 , 9 ). Although many of the current quality-of-life measures use self-report strategies, the components included in such measures are based on literature that is written from the researcher's perspective ( 8 ). Prince and Prince ( 10 ) suggested that an approach that integrates the individual's definition of what he or she considers to be a good quality of life is likely to be the best indicator of subjective quality of life and that "a measure that has been developed from client-elicited subjective quality of life domains may have the potential to resolve the failure of existing measures to register meaningful change."

The purpose of this study was to explore the construct of quality of life from the perspective of individuals diagnosed as having severe and persistent mental illness, such as schizophrenia.

Methods

Qualitative research strategies, specifically in-depth interviews and focus groups, were used to explore the construct of quality of life. In addition, the first author explored enablers that participants believed helped or would help them achieve a satisfactory quality of life and barriers that prevented them from achieving a satisfactory quality of life. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Western Ontario and from ethics review boards of Regional Mental Health Care St. Thomas. To be included in this study, participants were required to have a diagnosed mental illness, be between the ages of 18 and 70, and be willing and able to provide written consent. Participants were recruited through their treating clinicians or consumer survivor agencies. A snowball sample of convenience was used for recruitment.

Fifty-three individuals participated in this study. Over a 16-month period (October 2002 through February 2004) individuals were recruited for this study; 18 individuals gave in-depth interviews and 35 participated in focus groups. Table 1 shows the demographic data for the participants. The first author conducted all interviews and focus groups. Interviews and focus groups took place in hospitals, community clinics, community agencies, and clients' homes. The six focus groups were composed of six to eight individuals. A semistructured interview guide was used for interviews. Interviews lasted approximately an hour to an hour and a half. All interviews and focus groups were audiotaped and transcribed. Several trustworthiness strategies were employed to ensure credibility, including member checking, triangulation, peer debriefing, thick description, and an audit trail. Transcripts were analyzed by using the constant comparative method. More details regarding methods, recruitment, and analysis can be found in a dissertation by Corring ( 9 ). [An appendix showing selected verbatim quotations is available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

|

Results

Two overarching themes, four domains, and several subcomponents were identified. The two dominant themes permeated all of our results, crossing all domains, influencing the linkages between domains, and clearly influencing how individuals framed their expectations regarding quality of life. The first theme was the presence of stigma among individuals with mental illness as experienced and anticipated from persons with whom they interact, as well as the self-stigma and stigmatizing attitudes toward their peers. In a very profound way stigma influenced the actions of individuals living with mental illness in everyday life as well as their planning for the future. The second theme was the pervasive fear of the positive symptoms of psychoses—such as hallucinations, delusions, and general loss of contact with reality—and the subsequent perceived need for constant vigilance regarding the reoccurrence of psychotic symptoms. In addition, four domains were identified—the experience of illness, relationships, occupation, and sense of self. They, and their subcomponents, are described more fully below.

The experience of illness

Living day to day with a psychotic illness was described as a very frightening and isolating experience. The participants described their sense of fear while experiencing symptoms, watchfulness for reoccurrence of illness, concerns over safety, experiences of anxiety and rejection in interactions with others, avoidance of stressors, feelings that they were being treated as "fragile" by their families, and a sense of powerlessness in gaining control over symptoms. All of these concerns that they reported contributed to a sense of the illness having a "tyrannical" power over their lives. There were several accounts of how medication had successfully controlled symptoms and provided relief and several accounts of unsuccessful medication trials. Medication side effects continued to have a troubling effect on individuals to varying degrees.

The loss of life roles—that is, roles in life that are expected by others and hoped for by the individual—was also talked about by participants and was acknowledged as part of the experience and burden of these illnesses. Finally, limited financial resources resulted in individuals' having to make choices, choices that often meant having to give up what many of us take for granted as basics in life—that is, recreational opportunities and suitable living accommodations.

The importance of living one day at a time—for some, one hour at a time—was emphasized. This requires not living in the past, not allowing oneself to become overwhelmed by day-to-day life, and not allowing oneself to be preoccupied with thoughts. Many participants talked about the benefits of gaining an understanding of their illness. Information regarding the probable causes of their symptoms, what to expect for the future, the importance of taking medication, and strategies to use to manage their illness were all considered to be beneficial. Identifying coping strategies, and therefore, a feeling of gaining some control over the illness and the side effects of the medication, helped individuals to feel more optimistic about their future.

Relationships

The participants in this study talked about many different relationships: relationships with family, with intimate others, with friends, with peers with mental illness, and with service providers. They described how these relationships can be an enabler, a barrier, or both to achieving quality of life.

Supportive family members played an enormous and positive role in providing much needed caring and understanding for individuals living with these illnesses. When families were not supportive or when families became disrupted as a result of dealing with the behavior often associated with the illness, the burdens already experienced by the individual with mental illness were increased. However, it should be noted that the burden, disappointment, and confusion that these illnesses create for families cannot be underestimated.

Persons with a severe mental illness said that they valued intimate relationships. Although they did not always talk about relationships, many placed it high on the list of important things to achieve in life. The importance of having someone there to support you and someone to come home to cannot be overestimated. Preparing for the possibility of having an intimate relationship required extra thought for persons experiencing these illnesses. Many anticipated that there would be negative reactions to their illness if they were to tell the other person about their illness. Persons in a relationship who experienced negative reactions from their partner suffered from the lack of support.

Good friends contributed enormously to quality of life. However, participants described how they often deliberately isolated themselves in order to save their friends from having to observe them experiencing the illness that they themselves found so frightening. Isolation protected them from anticipated negative reactions from others. Not surprisingly, when friends pull away from the person who becomes ill, there can be lasting effects on the self-confidence of the individual.

The participants in this study provided many descriptions of the importance of relationships with others who shared their illness experience. These "sympathetic others … who share the stigma" provided support and offered the "comfort of feeling at home, at ease, accepted as a person who really is like any other normal person" ( 11 ).

Service providers and professionals contributed positively to quality of life through engaging with their clients in a relationship that was supportive and caring. Taking the time to listen, to be kind, to understand, to treat them like an adult, and to not judge them was critically important to the service recipients. Alternatively, service providers and professionals who did not seek to understand the person behind the illness, who treated the individual as an illness rather than as a human being, or who failed to respect the individuality of a person's need added to the burden for those living with the illness.

Occupation

Not being active often led individuals to a downward spiral in which they lacked energy, lacked motivation, were preoccupied with thoughts, and became isolated. Participants emphasized the importance of "making the choice to be part of things" and being active socially on a regular basis. This could mean competitive employment or volunteer work. Many participants promoted activity of any kind as a way of keeping themselves healthy, building self-confidence, and feeling useful. Several of the participants in the focus groups were employed part-time in businesses run by consumer-survivors or community agencies. In the competitive work world these individuals frequently experienced stigmatizing attitudes.

Sense of self

Many individuals had experienced reactions from others that left them cautious about disclosing their illness or even associating with others. Many described being hurt by the comments and actions of others and feeling as though the media adds to the negative public perception of persons with mental illness. Individuals living with severe and persistent mental illnesses suffered from another form of stigma—self-stigma—perhaps the most powerful of all stigmas, because it affects the inner sense of self in very profound ways. Although it was not always easy, people with mental illness strived to build a positive self-image. Participants said that part of building a more positive self-image was the satisfaction gained from helping others. Individuals who had been part of the service system for a long time felt a need to "give back" and derive a sense of reward by helping others. The importance of spirituality to quality of life and building a sense of self was emphasized by participants in the focus groups. For some, spirituality was found in formal religion; for others it was the importance of believing in something bigger than oneself.

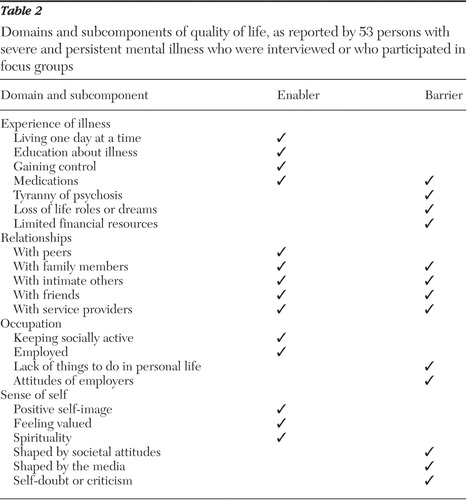

Table 2 summarizes the domains and subcomponents discussed above and indicates whether each subcomponent acts as an enabler, a barrier, or both.

|

On the basis of the results of this study, the Corring quality of life interview protocol was developed but is not reported on here. For further information regarding the protocol please contact the first author.

Discussion

The results of this qualitative study raise many issues in regard to the adequacy of current quantitative measures used to evaluate quality of life, suggesting that explorations of this very complex construct should employ methods that address the personal, idiosyncratic meanings and importance of life experiences. Most of the existing measures evaluate the experience of illness as it pertains to symptoms and side effects, but they do not sufficiently explore illness burden or illness recovery issues ( 8 ). Many existing measures examine the presence—but not the quality—of social relationships, levels of social support, and living situations. Most of these measures examine the level of activity or use of time by the individual, but they fail to examine the "meaningfulness" of these occupations and the barriers that stigma can present to acquisition of a valued occupation. Finally, a few of these measures seek to evaluate the effect of others on self or they focus on psychological well-being and the effects of distress as a means to understanding the effects of the illness on sense of self, but they do not examine in depth the way in which the sense of self is shaped by the attitudes of society and by a person's feelings of self-stigma.

Stigma toward persons with mental illness has been identified as a major challenge for some time. Thirty years ago Judy Chamberlin's book On Our Own: Patient-Controlled Alternatives to the Mental Health System helped give birth to the phrase "Nothing about us without us," which became the mantra of the consumer movement in the United States ( 12 ). More than ten years earlier Farina and colleagues ( 13 ) had conducted an experimental study on the impact of stigma and found that stigma did lead to discrimination in employment, in physicians' offices, and in the psychiatric hospital. Struening and colleagues ( 14 ) reported that "having once been a patient in a mental hospital is a notable experience. It is a kind of unwelcome legacy that must be endured until it is somehow conquered…. It is stigma that lurks in the hearts, minds and fears of many people."

Williams and Collins ( 15 ) contended that despite the new expectations communicated by the World Health Organization ( 16 ) stating that people living with schizophrenia can recover from the effects of the illness, "people with schizophrenia continue to live in an environment in which both the general public and health professionals have low expectations for them. Notably these stereotypes need not refer solely to the long-term patient. It appears that chronicity has not been defined solely by length of illness or persistence of symptoms but has also been encompassed by judgments about social functioning."

Participants in the study talked about the desire to be seen as "normal" human beings. The issue of what is normal is a complex one. In an article that reviewed the International Classification of Impairment, Disability, and Handicap and its need for revision, Hahn ( 17 ) noted that the term "normal" is a relatively recent addition to the English language. The term "normal" first appeared in a dictionary in 1828, and the term "abnormal" later appeared in 1853. In its original definition, "norms" were meant to represent typical ways of doing things. It was not intended that norms should be seen as "the ideal goal towards which all must strive." Pfeiffer ( 18 ) argued that the definition of normal is tied to culture. What is normal in one society can be considered abnormal in another. In the Western culture, behavior that is not normal leads to stigmatizing attitudes and behaviors, which persons with disability experience on a frequent basis. Advocates from the disability community challenge health care professionals to view disability as more than the result of medical illness or injury and to recognize the impact of societal attitudes and values ( 17 , 19 ).

When participants in this study were consistently treated as different from the norm, the effects of stigma became internalized and self-stigma influenced their sense of self.

The results of this study appear to indicate that the symptoms of severe mental illness (the impairment) and societal reactions to and expectations of persons with severe mental illness are both instrumental in the development and unfolding of disability. This study suggests that complex and varied interplay of impairment and social factors must be included in studies examining quality of life.

The prognosis for individuals diagnosed as having schizophrenia in the past five to ten years is significantly better than it was in prior years ( 16 , 20 , 21 ), and yet many, even many mental health professionals, do not recognize the potential for recovery ( 20 ).

Conclusions

One study participant described how even the basics can improve quality of life: "Well, I think you have to be happy with what you've got or happy with what you can negotiate with other people. Like, where I live we have a good quality of life because we have an open kitchen … anytime she's [the landlady is] not preparing meals, you can go in and you have a snack. On weekends we have a movie on DVD…. The [landlady's} kind enough to do that for us … so that kind of helps in your quality of life…. It makes you feel like a human being."

Participants in this study talked about wanting to be seen as "normal." The attainment of "normal" status continues to be elusive because of the continuing effects of stigma on persons with mental illness. They spoke of wanting a normal, ordinary life, but in actual fact, many have lowered expectations. There were no expectations of expensive cars and homes or high-profile careers, and there was no exaggerated sense of self-importance. Participants in this and other studies ( 21 , 22 ) were willing to settle for the basics in life—mental and physical health, supportive relationships, meaningful occupations, and a positive sense of self—believing that acquisition of these basics would lead to a more satisfactory quality of life. Quality of life for individuals living with mental illness is an intensely personal experience. Each person places more or less importance on one or more of these domains, depending on their individual situation.

Strauss ( 23 , 24 ) emphasized the importance of exploring the subjective experience of the person experiencing the illness. He stressed the importance of listening to the person's story about his or her life and illness experiences. We have provided many illustrations of how qualitative inquiry can assist in this endeavor as we seek to ask, listen, and learn from these individuals ( 25 ).

Ensuring changes to social, cultural, and economic conditions should not be the responsibility of the person with the illness. The onus should be on the society in which he or she lives. Attitudes are extremely difficult to change; however, legislation requiring change has demonstrated that change is possible. Persons with severe and persistent mental illness want what "normal persons" want, but they are willing to settle for so much less. As a society we could and should provide so much more.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Funding for this project was provided by the St. Joseph's Health Care London Foundation.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Awad GA, Voruganti LN: Intervention research in psychosis: issues related to the assessment of quality of life. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:557-564, 2000Google Scholar

2. Awad GA: Quality and the challenge for psychiatric practice. CPA Bulletin October:132-133, 1999Google Scholar

3. Farquhar M: Elderly people's definition of quality of life. Social Science and Medicine 41:1439-1446, 1995Google Scholar

4. McGee HM, O'Boyle CA, Hickey A, et al: Assessing the quality of life of the individual: the SEIQoL with a healthy and gastroenterology unit population. Psychological Medicine 21:749-759, 1991Google Scholar

5. Prince PN, Gerber GJ: Measuring subjective quality of life in people with serious mental illness using the SEIQoL-DW. Quality of Life Research 10:117-122, 2001Google Scholar

6. Simmons S: Quality of life in community mental health care: a review. International Journal for Nurses Studies 31:183-193, 1994Google Scholar

7. Wolf JR: Client needs and quality of life. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 26:16-24, 1996Google Scholar

8. Lehman AF: A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning 11:51-62, 1988Google Scholar

9. Corring DJ: Being Normal: Quality of Life Domains for Persons With a Mental Illness. Ph.D. dissertation, London, Ontario, Canada, University of Western Ontario, Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, 2005'Google Scholar

10. Prince P, Prince C: Subjective quality of life in the evaluation of programs for people with serious and persistent mental illness. Clinical Psychology Review 21:1005-1036, 2001Google Scholar

11. Goffman E: Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. New York, Simon and Schuster, 1963Google Scholar

12. Chamberlin J: On Our Own: Patient-Controlled Alternatives to the Mental Health System. New York, McGraw Hill, 1978Google Scholar

13. Farina A, Allen JG, Saul BB: The role of the stigmatized in affecting social relationships. Journal of Personality 36:169-182, 1968Google Scholar

14. Struening EL, Perlick DA, Link BG, et al: The extent to which caregivers believe most people devalue consumers and their families. Psychiatric Services 52:1633-1638, 2001Google Scholar

15. Williams CC, Collins AA: The social construction of disability in schizophrenia. Qualitative Health Research 12:297-309, 2002Google Scholar

16. Mental Health: New Understandings, New Hope. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2001Google Scholar

17. Hahn H: Assessing scientific measures of disability. Journal of Disability Policy Studies 12:114-121, 2001Google Scholar

18. Pfeiffer D: The ICIDH and the need for its revision. Disability and Society 13:503-523, 1998Google Scholar

19. Harding CM: Beautiful minds can be recovered. The Voice: Newsletter of the International Association of Psycho Social Rehabilitation Services, Nov 2002, pp 7, 8Google Scholar

20. Harding C, Strauss JS, Zubin J: Chronicity in schizophrenia: revisited. British Journal of Psychiatry 161:27-37, 1992Google Scholar

21. Leff J, Dayson D, Gooch C, et al: Quality of life of long-stay patients discharged from two psychiatric institutions. Psychiatric Services 47:62-67, 1996Google Scholar

22. Borge L, Martinsen EW, Ruud T, et al: Quality of life, loneliness, and social contact among long-stay psychiatric patients. Psychiatric Services 50:81-84, 1999Google Scholar

23. Strauss JS: The person-key to understanding mental illness: towards a new dynamic psychiatry, III. British Journal of Psychiatry 161:19-26, 1992Google Scholar

24. Strauss JS: The person with schizophrenia as a person: II. approaches to the subjective and the complex. British Journal of Psychiatry 164:103-107, 1994Google Scholar

25. Corring DJ, Cook JV: Ask, listen and learn: what clients with a mental illness can teach you about client-centred practice, in Client-Centred Practice in Occupational Therapy, 2nd ed. Edited by Sumsion T. Edinburgh, Churchill Livingstone, 2006Google Scholar