Differences in Lifetime Use of Services for Mental Health Problems in Six European Countries

In most countries, mental disorders often go untreated, and access to mental health care is considered insufficient ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ). Likely reasons to explain this situation lie in the availability and cost of services, as well as in their organization, especially the interaction between primary and specialized care ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 5 ). Sociocultural factors, such as knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders as well as the degree of stigmatization of mental illness in society, also have been implicated as a cause of underutilized services ( 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ).

ESEMeD/MHEDEA 2000 investigators

The European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders/Mental Health Disability: A European Assessment in Year 2000 (ESEMeD/MHEDEA 2000) included, in addition to the authors listed in the byline, the following investigators:

Sebastian Bernert, M.Sc.

Department of Psychiatry, University of Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany

Ronny Bruffaerts, M.A.

Department of Neurosciences and Psychiatry, University Hospital Gasthuisberg, Leuven, Belgium

Giovanni de Girolamo, M.D.

Department of Mental Health, Azienda Unità Sanitaria Locale di Bologna, Bologna, Italy

Ron de Graaf, Ph.D.

Netherlands Institute of Mental Health and Addiction, Utrecht, the Netherlands

Koen Demyttenaere, M.D., Ph.D.

Department of Neurosciences and Psychiatry, University Hospital Gasthuisberg, Leuven, Belgium

Isabelle Gasquet, M.D.

University Hospital Paul Brousse, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, Paris, France

Steven J. Katz, M.D., M.P.H.

Health Services Research, University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center, Ann Arbor, Michigan

Ronald C. Kessler, Ph.D.

Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

Jean-Pierre Lépine, M.D.

Department of Psychiatry, Hôpital Lariboisière Fernand Widal, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, Paris, France

Johan Ormel, Ph.D.

Department of Psychiatry, University Hospital Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands

Gabriella Polidori, M.D.

National Institute of Health, Rome, Italy

Gemma Vilagut, B.Sc.

Health Services Research Unit, Institut Municipal d'Investigació Mèdica, Barcelona, Spain

Only a limited number of comparative studies using standardized methods and diagnostic criteria have been published on utilization of mental health care ( 1 , 3 , 5 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ). Although these studies suggest, interestingly, that the Netherlands and the United Kingdom have better access to care than North America and similar access to that provided in Australia, they are based on rather different methodologies and very different health care systems. In North America, access to care seems to have increased, however, in the past ten years ( 13 ).

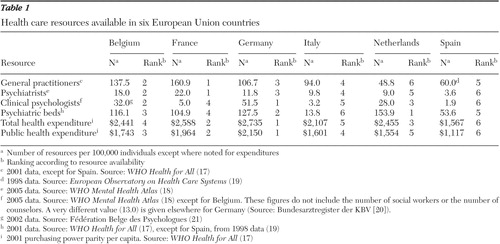

The European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders survey (ESEMeD) ( 15 ) gave us an opportunity to compare mental health care, using identical instruments and definitions, among six countries in the European Union (EU). The EU is a unique economic entity, where health insurance levels are relatively similar but where levels of resources and the organization of mental health services differ markedly ( 16 ). This comparison provides information about the relationship between the quantity and type of available resources ( Table 1 ) and the proportion of individuals who use these services. We used the most recent data available at the time of the study, which included data from the World Health Organization ( 17 , 18 , 19 ) and from professional associations in Germany ( 20 ) and Belgium ( 21 ). In particular, we address the question of whether more resource provision corresponds to higher use of services, either in general or among those with mental disorders.

|

Methods

ESEMeD was a cross-sectional survey, the target population of which was the noninstitutionalized adult population (18 years or older) of Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Spain (approximately 213 million adults). A stratified, multistage, clustered-area probability sample design was used. The sampling frame and selection procedures were as described previously ( 22 ).

Individuals were asked for their informed consent to participate in a face-to-face interview. Questions were administered at home by trained interviewers who used a computer-assisted personal interview that included the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) ( 23 ). The interview procedure consisted of two phases ( 15 ). During phase 1, all respondents provided information for diagnostic assessment of the most common mood and anxiety disorders, as well as data on health-related quality of life, health services utilization, and demographic characteristics. Only those who exceeded a number of symptoms of specific mood or anxiety disorders and a random 25% of the other respondents were included in phase 2, which consisted of an in-depth interview about additional mental disorders, self-reported chronic physical conditions, and risk factors, among other information.

Data were obtained from 21,425 respondents between January 2001 and July 2003. The overall response rate was 61.2%, with the highest rates in Spain (78.6%) and Italy (71.3%), followed by Germany (57.8%), the Netherlands (56.4%), Belgium (50.6%), and France (45.9%). In this study we analyzed the phase 2 subsample only (N=8,796). "The overall sample" in the text refers to this population.

Mental disorders

The questionnaire was based on the CIDI (version 3.0), which was developed and adapted by the Coordinating Committee of the World Health Organization's World Mental Health 2000 Initiative ( 24 ). This instrument, which has proved feasible, reliable, and valid for use in different cultures and settings ( 24 , 25 , 26 ), provides, by means of computerized algorithms, lifetime and current diagnoses of mental disorders according to DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria. The following disorders were assessed: mood disorders (major depression and dysthymia), anxiety disorders (social phobia, specific phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, agoraphobia with or without panic disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder), and alcohol use disorder (dependence and abuse). Other disorders included on the CIDI questionnaire, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, eating disorders, drug use, childhood disorders, and psychotic disorders, were not considered in this study because they were assessed in only a small subsample of respondents.

Service use

All participants were asked to delineate lifetime use of any service as a result of their "emotions or mental health problems." Individuals reporting use of services were then asked to select the type of provider they had seen from a list of formal health care providers (including psychiatrists; psychologists, also called "nonmedical mental health providers" in the text, which included psychotherapists, social workers, and counselors; nurses; general practitioners; and other medical doctors) and of informal providers (such as religious advisors and other healers). In this study, any services, formal and informal, were considered.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses with Stata 8.1 software were weighted for sample design and nonresponse in order to represent the adult population of each country ( 22 ) for lifetime diagnoses of mental disorders and lifetime use of care. The chi square test was used to compare ratios. Multiple logistic regression analyses were used to assess the influence of demographic variables, clinical variables, and country on the use of services.

Results

Sample

Participants were typically between 25 and 64 years old (67.9%), married (66.8%), and living in towns that had more than 10,000 inhabitants (66.8%). Approximately half were women (51.8%). A minority (34.6%) had a low education level.

Lifetime consultation rates for mental health problems

All countries had a consistent pattern of consultation ( Table 2 ), with the highest lifetime rates observed among respondents with mood disorders and the lowest among those without any mental disorder. The presence of comorbid disorders was associated with increased consultation rates. In contrast, consultation rates among those with alcohol-related disorders were relatively low compared with those found among respondents with other disorders. When all countries were compared, significant intercountry differences were observed for all disorders. The most striking differences observed were between Italy, with the lowest consultation rates for almost all disorders, and the Netherlands, with the highest. Participants with a mood disorder in the Netherlands were twice as likely as their Italian counterparts to have sought professional help (71.0% versus 37.0%; p<.001). A similar difference between these two countries was found among those with an anxiety disorder (63.6% versus 33.1%; p=.001) and alcohol use disorder (45.9% versus 16.5%; p= .020). Spain had a rather low consultation rate among respondents without any mental disorder but relatively high rates among those fulfilling diagnostic criteria for mental disorders (with the exception of alcohol use disorder).

|

Multiple logistic regression analyses ( Table 3 ) showed that, in the overall sample, women were more likely to consult than men. Similarly, people who had been divorced, those with a higher education level, and those living in an urban area were more likely to seek services. Respondents in the youngest age group (18-24 years) and in the oldest one (65 years and older) were about 50% less likely to have sought professional help than those 25-64 years old. The probability of seeking help was increased by the presence of a lifetime mental disorder, even more so when it presented with a co-occurring mental disorder. Multiple logistic regression analyses also confirmed a lower level of consultation in Italy and Spain than in Belgium, France, Germany, or the Netherlands.

|

Observed consultation rates were generally consistent with the availability of professionals, especially of those who specialized in mental health. The lowest consultation rates were observed in the countries with the lowest availability. However, the reverse seemed not to be necessarily true: the Netherlands had a high consultation rate consistent with a high density, especially of psychologists; on the other hand, Belgium, France and Germany, which have a relatively high number of health providers, showed an intermediate consultation rate.

Type of provider consulted

When the type of professional consulted was examined among all participants who had already used services for mental health problems ( Figure 1 ), we found that general practitioners were the main providers in all countries. Lifetime consultation rates ranged from 54.6% in Italy to 72.7% in Belgium and France (p<.001). The second most consulted professional was, in general, the psychologist, with the highest consultation rate in the Netherlands (64.8%) and the lowest in France (23.3%; p<.001), but a wide variation was observed. The consultation rate for psychiatrists ranged from 25.5% in the Netherlands to 43.8% in Spain (p=.03). The use of other doctors was highest in Italy (29.1%; p<.001), as was the consultation of religious advisors (12.3%; p<.001).

Among users of services, observed consultation rates for general practitioners were generally consistent with the number of professionals available in the different countries—highest in Belgium and France and nearly the lowest in Spain. However, the Netherlands, which has the lowest number of general practitioners, showed a high contact rate, whereas Germany and Italy had a relatively lower consultation rate than would be expected from the availability of general practitioners in those countries. Psychiatrist use was remarkably similar in countries with very different levels of availability and was notably high in Spain, which has the fewest psychiatrists. Use of nonmedical mental health providers also differed from patterns of availability, with a very high level of use in the Netherlands, which has half as many professionals as Germany has.

Use of a mental health professional versus a general practitioner

By selecting all participants who had already consulted either a mental health professional or a general practitioner and using multiple logistic regression analyses ( Table 4 ), we found that older individuals (65 years and older) and those with a lower education level were about half as likely to have consulted a mental health professional for their problems with or without consulting a general practitioner first, instead of consulting only a general practitioner. On the other hand, single persons were more likely than married or divorced persons to consult a mental health professional. Concerning mental health status, the presence of lifetime mental disorders increased the probability of consulting mental health professionals, especially when a comorbid condition was present. Belgians and the French were less likely than persons from the other four countries to have consulted a mental health specialist. This finding reflects the high density of general practitioners in these two countries.

|

General practitioner referral to mental health professionals

When all participants who had already consulted a general practitioner were asked if they had been referred by the practitioner to a mental health specialist, a very diverse pattern was found. The referral rate was the highest in Italy, followed by the Netherlands and Spain for almost all the categories and the lowest in France, but it was low also in Belgium and Germany, even though the latter two had relatively higher referral rates. For example, French clients were referred to mental health specialists by their general practitioner in only 22.2% of cases, as opposed to 55.1% in Italy, 52.8% in the Netherlands, and 40.4% in Spain (p<.001). The same trend was found for individuals with a mood disorder, an anxiety disorder, or both (p<.001 for all comparisons).

Observed referral rates were fairly consistent with the availability of general practitioners, being highest in the Netherlands and Spain—countries with a low density of professionals—and lowest in Belgium and France, where there are many general practitioners. However, this relationship did not hold in Germany and Italy, which have a similar density of general practitioners but show quite different patterns of referral.

Discussion

Levels of consultation for mental health problems differed between the six countries that were analyzed (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Spain). Differences were also observed in the type of professionals consulted and the extent of referral to specialists. Intercountry consultation differences observed in this study were not clearly related to resource availability.

Italy and Spain showed consistent low consultation rates and a low density of professionals, especially those specialized in mental health. However, Spain showed, especially among those with a mental disorder, much higher consultation rates than Italy, which has a relatively higher resource availability but the lowest consultation rates. This difference might be accounted for by a more efficient use of resources in Spain, characterized by a relatively high referral rate to psychiatrists for individuals suffering from a mental disorder. Although the Netherlands has a low density of general practitioners and psychiatrists, this country had a high level of consultation, which was somewhat consistent with the number of nonmedical mental health professionals. A high rate of referral to specialists and a large use of nonmedical mental health professionals may be the likely explanation of this pattern. Belgium, France, and Germany, despite a high level of resource availability, showed an intermediate level of consultation as well as low rates of referral to specialists.

Comparisons with previous studies

Our results show some similarities with studies performed in the United Kingdom ( 11 , 12 ), which reported that major determinants of treatment access for mental problems are symptom severity, reflected in this study by comorbidity of mental disorders, and age. Furthermore, the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study reported that patients with mood disorders were more likely to enlist professional help than those with alcohol- and drug-related disorders ( 10 ).

Nonetheless, comparisons of previous reports on mental health provision in individual European countries are limited by the different sampling techniques and the different diagnostic instruments used, with six different instruments being used in 11 recent studies ( 27 ). There have been only two reports that used comparable assessments of the mental health of adults in more than one European country: the European Outcome of Depression International Network ( 28 ) and the Depression Research in the European Society ( 29 , 30 ) studies. However, these studies were limited in that the former corresponded to comparisons between local community or primary care registration samples that were not representative of the general population of the participating countries, whereas the latter focused entirely on depressive disorders with some methodological limitations in the sampling design and achieved fieldwork.

On the other hand, a study across Europe of the mental health status of the European population in the previous 12 months (Eurobarometer) ( 31 ) reported patterns of use similar to this study. For example, the likelihood of seeking any help for a mental health problem was found to be the highest in the Netherlands and the lowest in Italy and Spain.

Comparing resources and use of care

The main hypothesis tested in the study was that countries with more resources for psychiatric or psychological treatment would show a higher service utilization rate. However, the patterns of health care use observed among countries did not, on the whole, always correspond to actual resource availability, although the lowest consultation rates generally corresponded to the lowest resources. For instance, even though Belgium has nearly three times the number of general practitioners per capita as the Netherlands, the lifetime consultation rates for these professionals were practically identical in the two countries. Similarly, the country with the lowest density of psychiatrists, Spain, had a higher use of psychiatrists (43.8%) than Belgium (36.2%) or France (34.7%), countries with a high density of these specialists.

These findings suggest that use of resources appears to be mediated by other factors, such as the nature of professionals, referral practice, and sociocultural factors, which have been studied in depth elsewhere ( 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ). For example, Italians are less likely than their other European counterparts to consult formal health care providers for their mental health problems. In contrast, Italians seek relatively more help from religious advisors. In addition, how resources are financed might be relevant to explaining patterns of health care use. The different levels of health care insurance and the requirements for out-of-pocket expenditures, such as copayments ( 3 , 5 ), could explain intercountry differences in utilization of services to a certain extent. For example, in France costs of psychotherapy are reimbursed if practiced by a psychiatrist but not when provided by a psychotherapist who is not a physician; in the Netherlands, on the other hand, psychotherapists are integrated into the health system, and their services are free of charge.

Limitations and strengths of the study

This study has several limitations. First, visits to health providers were self-reported. Reporting on past events is likely to be particularly prone to recall bias. In addition, many users of services for mental health problems might not have considered they had a mental health problem and might not have been captured in this section of the survey interview, which could lead to an underestimate of use of services. The extent of this phenomenon could vary between countries in an unidentifiable way.

Second, results are related to lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders. This period is useful in that it maximizes exploitable information by increasing the number of participants considered, and it gives an idea of the overall access to care for people in need. On the other hand, the disadvantages of using lifetime measures are recall bias and the existence of some age-related bias resulting from the inevitable higher probability of consulting for older individuals.

Third, certain disorders included on the CIDI questionnaire, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, eating disorders, drug use, childhood disorders, and psychotic disorders, were not considered in this study because they were assessed in only a small subsample of respondents.

Fourth, survey participation rates were low in some countries. Nevertheless, nonresponse could have been overestimated occasionally, for example in France, where nonrespondents included individuals who never answered the telephone ( 27 ). Nonrespondents may use health services differently from respondents. This difference could introduce a potential bias, especially in the case of France and Belgium, which had the lowest participation rates. However, this difference should not have an impact on the results of our intercountry comparison because higher participation would be expected to have a significant impact only on the trends observed in extreme scenarios where nonrespondents differ drastically from respondents.

Fifth, we did not consider the number of consultations in our analysis. It might be that differences between countries change when considering intensity of use.

Sixth, certain resources (for example, mental health expenditure and number of psychotherapists, social workers, or counselors) were not examined because of the absence of available data.

Finally, only availability of services was compared between countries, and other relevant issues, such as organization and financing, were not addressed.

ESEMeD is, however, the largest comparative study of mental disorders in the EU to date in terms of size of the sample and the populations represented, the range of mental disorders assessed, and the information collected ( 32 ). This study provides a first attempt at assessing intercountry differences in access to mental health care, which needs to be refined by taking into account other important determinants, such as quality of care and outcome.

Conclusions

Health care use for mental health problems varies considerably among the six European countries compared in this study. Our results show that more available resources do not always result in greater use of services for people with mental disorders. Other factors, such as the nature of professional support available, referral practice, sociocultural factors, and financing, may also play a key role in access to care.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This project was funded by contract QLG5-1999-01042 and Sanco 2004-123 from the European Commission, the Piedmont Region (Italy); by grant FIS-00-0028 from the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain; by grant SAF 2000-158-CE from the Ministerio de Ciencia Y Tecnología, Spain; by the Departament de Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya, Spain; by other local agencies; and by an unrestricted educational grant from GlaxoSmithKline. The European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) is carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative. The authors thank the WMH staff for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and data analysis. These activities were supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the U.S. Public Health Service (1R13-MH-066849, R01-MH-069864, and R01-DA-016558), Eli Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceuticals, and the Pan American Health Organization. The authors thank the statisticians Frédéric Capuano, M.Sc., and David Sapinho, M.Sc., for their technical assistance.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Alegria M, Bijl RV, Lin E, et al: Income differences in persons seeking outpatient treatment for mental disorders: a comparison of the United States with Ontario and the Netherlands. Archives of General Psychiatry 57:383-391, 2000Google Scholar

2. Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Hiripi E, et al: The prevalence of treated and untreated mental disorders in five countries. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 22(3):122-133, 2003Google Scholar

3. Kessler RC, Frank RG, Edlund M, et al: Differences in the use of psychiatric outpatient services between the United States and Ontario. New England Journal of Medicine 336:551-557, 1997Google Scholar

4. Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, et al: Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA 291:2581-2590, 2004Google Scholar

5. Katz SJ, Kessler RC, Frank RG, et al: Mental health care use, morbidity, and socioeconomic status in the United States and Ontario. Inquiry 34:38-49, 1997Google Scholar

6. Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, et al: "Mental health literacy": a survey of the public's ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Medical Journal of Australia 166:182-186, 1997Google Scholar

7. Jorm AF, Korten AE, Rodgers B, et al: Belief systems of the general public concerning the appropriate treatments for mental disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 32:468-473, 1997Google Scholar

8. Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, et al: Helpfulness of interventions for mental disorders: beliefs of health professionals compared with the general public. British Journal of Psychiatry 171:233-237, 1997Google Scholar

9. Jorm AF: Mental health literacy: public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry 177:396-401, 2000Google Scholar

10. Bijl RV, Ravelli A: Psychiatric morbidity, service use, and need for care in the general population: results of the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study. American Journal of Public Health 90:602-607, 2000Google Scholar

11. Bebbington PE, Brugha TS, Meltzer H, et al: Neurotic disorders and the receipt of psychiatric treatment. Psychological Medicine 30:1369-1376, 2000Google Scholar

12. Bebbington PE, Meltzer H, Brugha TS, et al: Unequal access and unmet need: neurotic disorders and the use of primary care services. Psychological Medicine 30:1359-1367, 2000Google Scholar

13. Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, et al: Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. New England Journal of Medicine 352:2515-2523, 2005Google Scholar

14. Andrews G, Henderson S, Hall W: Prevalence, comorbidity, disability and service utilisation: overview of the Australian National Mental Health Survey. British Journal of Psychiatry 178:145-153, 2001Google Scholar

15. Alonso J, Ferrer M, Romera B, et al: The European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD/MHEDEA 2000) project: rationale and methods. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 11:55-67, 2002Google Scholar

16. Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, et al: Use of mental health services in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Supplementum 420:47-54, 2004Google Scholar

17. WHO Health for All. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2005. Available at data.euro.who.int/hfadbGoogle Scholar

18. WHO Mental Health Atlas. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2005. Available at www.who.int/globalatlasGoogle Scholar

19. European Observatory on Health Care Systems: Health Care Systems in Transition: Spain. Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2000Google Scholar

20. Bundesarztregister der KBV, Berlin, Germany, 2000. Available at www.kbv.de/publikationen/grunddaten.htmGoogle Scholar

21. Fédération Belge des Psychologues, Brussels, Belgium, 2002. Available at www.bfp-fbp.beGoogle Scholar

22. Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, et al: Sampling and methods of the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Supplementum 420:8-20, 2004Google Scholar

23. Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, et al: The Composite International Diagnostic Interview: an epidemiologic instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Archives of General Psychiatry 45:1069-1077, 1988Google Scholar

24. Kessler RC, Ustun TB: The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:93-121, 2004Google Scholar

25. Wittchen HU, Robins LN, Cottler LB, et al: Cross-cultural feasibility, reliability and sources of variance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). The Multicentre WHO/ADAMHA Field Trials. British Journal of Psychiatry 159:645-653, 658, 1991Google Scholar

26. Wittchen HU: Reliability and validity studies of the WHO—Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): a critical review. Journal of Psychiatric Research 28:57-84, 1994Google Scholar

27. de Girolamo G, Bassi M: Community surveys of mental disorders: recent achievements and works in progress. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 16:403-411, 2003Google Scholar

28. Ayuso-Mateos JL, Vazquez-Barquero JL, Dowrick C, et al: Depressive disorders in Europe: prevalence figures from the ODIN study. British Journal of Psychiatry 179:308-316, 2001Google Scholar

29. Lepine JP, Gastpar M, Mendlewicz J, et al: Depression in the community: the first pan-European study DEPRES (Depression Research in European Society). International Clinical Psychopharmacology 12:19-29, 1997Google Scholar

30. Tylee A, Gastpar M, Lepine JP, et al: DEPRES II (Depression Research in European Society II): a patient survey of the symptoms, disability and current management of depression in the community. International Clinical Psychopharmacology 14:139-151, 1999Google Scholar

31. The European Opinion Research Group: Eurobarometer 58.2: The Mental Health Status of the European Population. Brussels, Belgium, European Commission, 2003Google Scholar

32. Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Lepine JP: The European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project: an epidemiological basis for informing mental health policies in Europe. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Supplementum 420:5-7, 2004Google Scholar