Critical Time Intervention for Reentry From Prison for Persons With Mental Illness

After the surge in incarceration during the past 30 years, an increasing number of individuals are now being released from prison, estimated to be up to 600,000 to 750,000 per year ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ). The estimates indicate that as many as 100,000 consumers of mental health services are returning to the community each year ( 4 , 5 ). These individuals often have co-occurring substance use problems and are more likely than other mental health service consumers to be poor and nonwhite ( 5 , 6 , 7 ).

Like their counterparts released from psychiatric hospitals, persons with mental illness released from prison reenter the community with many needs ( 4 ). Family and friends are often expected to facilitate reentry by providing housing, financial assistance, transportation, and personal support ( 8 , 9 , 10 ). Although it is customary for people leaving hospitals to have discharge plans that coordinate these supports with treatment, this is rarely the case for those leaving prison. Individuals typically leave prison without a reentry plan, except possibly a parole supervision condition. They enter an extreme life transition in which there are few, if any, rehabilitative resources for former prisoners, much less for those with behavioral health needs ( 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ). What is done by, for, and with these individuals under such stress can make the difference between a new life and a return to the old life at a greater risk for a new arrest.

Critical time intervention (CTI), a focused, time-limited intervention to build community connections to needed resources, has been shown to be effective for consumers making a transition to community housing after discharge from an institution ( 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ). This article proposes CTI as a promising model for enhancing support during the reentry process of prisoners with severe mental health problems and presents a conceptual framework for evaluating its effectiveness in this context.

The CTI model

CTI is a nine-month, three-stage intervention that strategically develops individualized linkages in the community and seeks to enhance engagement with treatment and community supports through building problem-solving skills, motivational coaching, and advocacy with community agencies. CTI workers can increase the number and strength of clients' ties to community resources, especially ties to behavioral health providers and other service providers. Although originally used with persons who were transitioning from homeless shelters to housing in the community, CTI has now been adapted for those leaving psychiatric hospitals. Its application to homeless families was featured in the President's New Freedom Commission Report ( 19 ), and the model is one of a handful of homelessness prevention interventions recognized in the National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Policies of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

CTI was first developed and tested in a randomized trial for people with mental illness who were moving into housing from New York City's Fort Washington Armory shelter ( 15 , 16 ). In that trial, persons who received CTI experienced fewer nights homeless during an 18-month follow-up period than those who received the usual case management services. One notable finding from this study was the durability of the effect; improved outcomes were sustained even after termination of the intervention after nine months ( 16 ). CTI has demonstrated cost-effectiveness for addressing homelessness ( 18 ). In the United States CTI has since been used with homeless families leaving shelters ( 20 ), men and women after discharge from inpatient psychiatric treatment ( 21 , 22 ), and homeless women with co-occurring disorders who were moving from a shelter into housing ( 23 ). In addition, studies of CTI for people leaving prison in the United Kingdom have recently begun ( 24 ).

The CTI intervention has two components. The first is to strengthen the individual's long-term ties to services, family, and friends. To whatever degree these supports are available, individuals with mental illness and those upon whom they depend often need assistance to work together. Moreover, many consumers have preferences for treatment that may not easily link with preferences of providers, landlords, friends, and families. CTI attempts to promote treatment engagement through psychosocial skill building and motivational coaching.

The second component of CTI is to provide emotional and practical support and advocacy during the critical time of transition. During a stay in an institution, an individual may develop strong ties to the institution and become habituated to having therapeutic and basic needs met on site. These individuals often return to an isolated life in the community. For this reason, CTI provides temporary support to the client as he or she rebuilds community living skills, while working with the client to develop a persisting network of community ties that will support long-term recovery and reintegration into the community.

CTI is not intended to become a permanent support system; rather it ensures support for nine months while the person gets established in the community. CTI workers are singularly focused on developing a support system that lasts, and most important, that fits the individual and the community to which the individual returns. Thus, in many ways, the robust element of the intervention is building a resilient network of community supports that continues after CTI ends.

The foundation of CTI rests on elements found in other evidenced-based models. The core elements include small caseloads, active community outreach, individualized case management plans, psychosocial skill building, and motivational coaching. The overall framework borrows from assertive community treatment models and training in community living ( 25 , 26 ), which introduced an approach with these common elements and which has been rigorously tested over the past 30 years ( 27 , 28 ). The community treatment strategies of CTI are also grounded in the evidence base for psychiatric treatment, substance abuse treatment, and psychosocial interventions. These interventions include elements of assertive outreach, illness management ( 29 ), motivational interviewing, chronic disease management, and integrated substance abuse treatment ( 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ). All of these interventions have been tested by experience and empirical investigation and have been found to improve outcomes.

From aftercare planning to reentry planning

In mental health services, the success of aftercare planning depends on the quality of personal and community connections. For people with mental illness, smaller, less diversified social networks are associated with higher rates of rehospitalization and unsatisfactory treatment outcomes ( 23 , 34 , 35 , 36 ). Tensions around adherence to medication regimens and periods of social isolation and antisocial behavior may strain relations with friends, family members, and professional providers ( 6 , 9 , 10 ). Co-occurring substance abuse can fracture prosocial ties and also support the formation of other social ties centered on substance abuse ( 37 ).

Reentry planning for persons with mental illness after incarceration is the counterpart to discharge planning for persons being discharged from a psychiatric institution. It aims to set in place a strategy for connecting individuals to housing, employment, and education and creating positive social ties to reinforce these connections. Ideally, reentry planning capitalizes on existing social connections, intervenes to preserve connections on the outside while a person is incarcerated, and builds new community connections ( 4 ). In practice, reentry planning is often no more than a new buzzword for loosely brokered services with few strategies for access to effective treatment or other supports ( 14 , 38 , 39 ). Typically, criminal justice agencies are the major provider of reentry services for former prisoners with mental illness ( 40 ). The mental health system has offered no comprehensive evidence-based models for this transition other than forensic assertive community treatment, an adaptation of assertive community treatment applied to prison release settings ( 41 ). A broader range of reentry models is needed for interventions that are driven by priorities of the mental health system in the context of the criminal justice process.

Although at a conceptual level CTI seems to apply well to the process of prisoner reentry, there are also key differences between prison release and discharge from a hospital or shelter that must be considered. For instance, the availability of basic postdischarge resources, such as housing, is likely to be constrained by probation, parole, or other criminal justice system factors. Also, although a shelter or hospital resident may make prerelease visits to potential housing and other community settings, prisoners typically cannot leave prison to help plan their life after reentry.

Co-occurring substance use disorders

Research shows that compared with persons who have single disorders, those with co-occurring diagnoses are more debilitated by their illnesses ( 42 ), have lower functioning capacity ( 43 , 44 , 45 ), are heavier users of expensive services ( 46 ), and are less likely to adhere to treatment expectations ( 47 , 48 ); they also have less desirable treatment outcomes ( 45 , 49 , 50 , 51 ). They have greater risk of involvement in the criminal justice system ( 52 ). The rate of co-occurring substance abuse among people with mental illness in the criminal justice system is substantial; approximately two-thirds of state prisoners with mental illness report being under the influence of alcohol or drugs at the time of their offense ( 5 ).

Blended service models, which integrate mental health and addiction services into a unified care approach, and specialized case management strategies that address situational barriers to care are among the innovative strategies developed to improve engagement and promote more positive client outcomes. The effectiveness of blended treatment is supported by a growing body of research, which has led SAMHSA and the National Institute on Drug Abuse to recognize it as a best practice for this population in both inpatient and outpatient care as well as for those involved with the criminal justice system ( 31 , 53 , 54 ). Further, the evidence supports active, outreach-oriented, flexible, individualized interventions that attempt to establish a safe and supportive environment for community living, including housing, work, and social relations ( 30 , 55 , 56 ). Such interventions include supervision by a psychiatrist trained in the treatment of co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorders and ongoing attention to relapse prevention and maintenance of motivation ( 30 , 55 , 56 ). One approach to integrated treatment that has been tested in conjunction with CTI is dual recovery therapy (DRT) ( 30 , 55 , 57 , 58 ). DRT supports case managers in using evidence-based substance abuse treatment therapies. It is a manualized set of structured group sessions combined with ongoing support of case managers to enhance motivation to engage in substance abuse treatment ( 59 , 61 , 62 ).

A conceptual framework to assess effectiveness

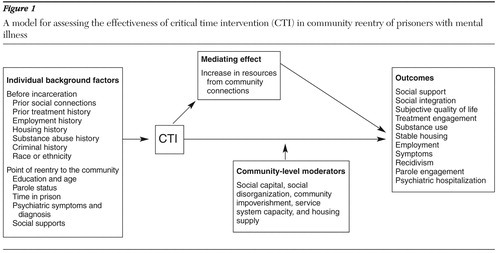

Only one randomized trial testing the effectiveness of CTI with persons with mental illness reentering the community from incarceration is currently being implemented. (For more information on this trial contact the first author.) This article presents a conceptual model from that trial of CTI effectiveness in reentry that combines an understanding of mental health outcomes and criminal justice outcomes ( Figure 1 ). The model addresses prisoner reentry as it applies to people with mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders. It emphasizes the role of community ties in individual and social outcomes.

In the model the CTI intervention is positioned as a connector between prison and community. Growth in community ties mediates the effect of CTI on consumer outcomes. This mediator represents a growth in social capital, conceptualized at the individual level ( 63 , 64 ). The model also includes community-level factors ( 64 , 65 ) that are included as potential moderators. Therefore, in addition to providing a framework for testing the effectiveness of the CTI intervention on mental health outcomes, we provide a theoretical framework for testing individual and community mechanisms that have an impact on outcome in reentry.

A key element in this model is the mediating effect of increases in resources that are embedded in social relationships. This is the "sticky" mechanism for CTI effectiveness that helps sustain the impact after the intervention is over. However, little research supports the effectiveness of interventions in increasing community connections. Research on the activities of CTI workers can develop this literature by documenting the effectiveness of this mechanism in regard to consumer outcomes in general, not just for prisoner reentry.

Housing is the single most critical need for persons with mental illness after discharge from any institutional stay, and it is often the most difficult need to meet. Housing for prisoners, ostensibly homeless at release, is often tenuously connected to social relationships. More reliable housing arrangements are frequently linked to formal services. Access to and continued tenure in housing may rely in part on the strength of the connection between the individual returning from prison and service providers ( 39 ).

Community impoverishment has been shown to explain involvement in the criminal justice system and prosocial outcomes among people in urban communities ( 66 , 67 ) Therefore, community-level factors are proposed in this model as a moderator. However, testing this effect in a randomized field trial setting may be challenged by limited variance in neighborhood-level variables for the neighborhoods involved, most of which are expected to be low in prosocial, legal economic options in terms of employment, housing, and daily activities.

Conclusions

Much work remains to be done toward developing and testing a variety of effective models to facilitate community reentry of persons with mental illness from different types of correctional facilities. The seven million to ten million persons who will be discharged from local jails in the United States each year is ten times the largest estimate of the number of persons leaving prisons ( 68 ). Prisons and jails represent different populations of individuals returning from incarceration and operate under different organizational constraints. They thus present unique challenges in implementing effective reentry strategies.

Among collaborative mental health and criminal justice interventions, the most impressive results to date have been obtained from interventions that rely on assertive community treatment, sometimes in a time-limited format, as the primary driver of consumer-level outcome ( 40 , 41 , 69 , 70 ). CTI presents an alternative that is specifically structured to build mental health system capacity to facilitate transitions, establish connections for reentering clients, and allow the connections to work. Principally founded on the values of the public mental health system, the goals of CTI are to connect consumers with sustainable formal and informal relationships in the community. CTI differs from most reentry programs that are initiated by the justice system ( 40 ) in its focus on the well-being of the consumer as a value at least on par with public safety. Hopefully, this approach will lead to reduced recidivism and reduced involvement in the criminal justice system among people with mental illness.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Support was provided by grant R01-MH-076068 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), from the Center for Mental Health Services and Criminal Justice Research (funded by NIMH grant P20-MH-068170), and from the Center for Homelessness Prevention Studies (funded by NIMH grant P30-MH-071430). The authors express their gratitude to Nancy Wolff, Ph.D., and Steven Marcus, Ph.D., for their comments and suggestions.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Visher CA, Travis J: Transitions from prison to community: understanding individua pathways. Annual Review of Sociology 29:89–113, 2003Google Scholar

2. Freudenberg N: Jails, prisons, and the health of urban populations: a review of the impact of the correctional system on community health. Journal of Urban Health 78:214–235, 2001Google Scholar

3. Goode J, Sherrid P: When the Gates Open: Ready4Work: A National Response to the Prisoner Reentry Crisis. New York, Public/Private Ventures, 2005Google Scholar

4. Draine J, Wolff N, Jacoby JE, et al: Understanding community re-entry of former prisoners with mental illness: a conceptual model to guide new research. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 23:689–707, 2005Google Scholar

5. Ditton PM: Mental Health and Treatment of Inmates and Probationers. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1999Google Scholar

6. Wolff N, Draine J: The dynamics of social capital of prisoners and community reentry: ties that bind? Journal of Correctional Healthcare 10:457–490, 2004Google Scholar

7. Draine J, Salzer M, Culhane D, et al: Poverty, social problems, and serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 53:899, 2002Google Scholar

8. Slaght E: Family and offender treatment focusing on the family in the treatment of substance abusing criminal offenders. Journal of Drug Education 19:53–62, 1999Google Scholar

9. Carlson BE, Cervera N: Inmates and Their Wives: Incarceration and Family Life. Westport, Conn, Greenwood, 1992Google Scholar

10. Hairston CF: Family ties during imprisonment: important to whom and for what? Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare 18:87–104, 1991Google Scholar

11. Garland DL: The Culture of Control: Crime and Social Order in Contemporary Society. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2001Google Scholar

12. Martinson RL: What works? Questions and answers about prison reform. Public Interest 35:22–54, 1974Google Scholar

13. Petersilia J: When Prisoners Come Home: Parole and Prisoner Reentry. New York, Oxford University Press, 2003Google Scholar

14. Marlowe DB: When "what works" never did: dodging the "Scarlet M" in correctional rehabilitation. Criminology and Public Policy 5:339–346, 2006Google Scholar

15. Lennon MC, McAllister W, Kuang L, et al: Capturing intervention effects over time: reanalysis of a critical time intervention for homeless mentally ill men. American Journal of Public Health 95:1760–1766, 2005Google Scholar

16. Susser E, Valencia E, Conover S, et al: Preventing recurrent homelessness among mentally ill men: a "critical time" intervention after discharge from a shelter. American Journal of Public Health 87:256–262, 1997Google Scholar

17. Herman D, Opler L, Felix A, et al: A critical time intervention with mentally ill homeless men: impact on psychiatric symptoms. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 188:135–140, 2000Google Scholar

18. Jones K, Colson PW, Holter MC, et al: Cost-effectiveness of critical time intervention to reduce homelessness among persons with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 54:884–890, 2003Google Scholar

19. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Pub no SMA-03-3832. Rockville, Md. Department of Health and Human Services, President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003Google Scholar

20. Samuels J: Critical Time Intervention for Homeless Families: Replication, Adaptation, and Findings. Washington, DC, American Public Health Association, 2004Google Scholar

21. Kasprow WJ, Rosenheck RA: Outcomes of critical time intervention case management of homeless veterans after psychiatric hospitalization. Psychiatric Services 58:929–935, 2007Google Scholar

22. Herman D: CTI in the Transition From Hospital to Community. Grant application, R01 MH59716-02. Bethesda, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 2001Google Scholar

23. Herman D, Conover S, Felix A, et al: Critical time intervention: an empirically supported model for preventing homelessness in high risk groups. Journal of Primary Prevention 28:295–312, 2007Google Scholar

24. Steel J, Thornicroft G, Birmingham L, et al: Prison mental health inreach services. British Journal of Psychiatry 190:373–374, 2007Google Scholar

25. Stein LI, Test MA: Alternative to mental hospital treatment: I. conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:392–397, 1980Google Scholar

26. Turner J, TenHoor W: Community Support Program: pilot approach to a needed social reform. Schizophrenia Bulletin 4:319–348, 1978Google Scholar

27. Penn DL, Mueser KT: Research update on the psychosocial treatment of schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:607–617, 1996Google Scholar

28. Mueser KT, Bond GR, Drake RE, et al: Models of community care for severe mental illness: a review of research on case management. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:37–74, 1998Google Scholar

29. Mueser KT, Corrigan PW, Hilton DW, et al: Illness management and recovery: a review of the research. Psychiatric Services 53:1272–1284, 2002Google Scholar

30. Drake RE, Mueser KT, Brunette MF, et al: A review of treatments for people with severe mental illnesses and co-occurring substance use disorders. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 27:360–374, 2004Google Scholar

31. Ziedonis DM: Integrated treatment of co-occurring mental illness and addiction: clinical intervention, program, and system perspectives. CNS Spectrum 9:892–904, 925, 2004Google Scholar

32. Miller WR, Rollnick S: Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior. New York, Guilford, 1991Google Scholar

33. Ziedonis DM, Trudeau K: Motivation to quit using substances among individuals with schizophrenia: implications for a motivation-based treatment model. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:229–238, 1997Google Scholar

34. Lehman AF, Kernan E, DeForge BR, et al: Effects of homelessness on the quality of life of persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 46:922–926, 1995Google Scholar

35. Wu T, Serper MR: Social support and psychopathology in homeless patients presenting for emergency psychiatric treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychology 55:1127–1133, 1999Google Scholar

36. Froland C, Brodsky G, Olson M, et al: Social support and social adjustment: implications for mental health professionals. Community Mental Health Journal 36:61–75, 2000Google Scholar

37. Granfield R, Cloud W: Social context and "natural recovery": the role of social capital in the resolution of drug-associated problems. Substance Use and Misuse 36:1543–1570, 2001Google Scholar

38. Draine J, Blank Wilson A, Pogorzelski W: Limitations and potential in current research on services for people with mental illness in the criminal justice system. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, in pressGoogle Scholar

39. Blank AE: Access for Some, Justice for Any? The Allocation of Mental Health Services to People With Mental Illness Leaving Jail. Doctoral dissertation. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania, School of Social Policy and Practice, 2006Google Scholar

40. Wilson AB, Draine J: Collaborations between criminal justice and mental health systems for prisoner reentry. Psychiatric Services 57:875–878, 2006Google Scholar

41. Lamberti JS, Weisman R, Faden DI: Forensic assertive community treatment: preventing incarceration of adults with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 55:1285–1293, 2004Google Scholar

42. Mares AS, Kasprow WJ, Rosenheck RA: Outcomes of supported housing for homeless veterans with psychiatric and substance abuse problems. Mental Health Services Research 6:199–211, 2004Google Scholar

43. Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, et al: The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: implications for prevention and service utilization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:17–31, 1996Google Scholar

44. Bartels SJ, Drake RE, McHugo GJ: Alcohol abuse, depression, and suicidal behavior in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:394–395, 1992Google Scholar

45. Newman DL, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, et al: Comorbid mental disorders: implications for treatment and sample selection. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 107:305–311, 1998Google Scholar

46. Osher FC, Drake RE: Reversing a history of unmet needs: approaches to care for persons with co-occurring addictive and mental disorders. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:4–11, 1996Google Scholar

47. Bartels SJ, Teague GB, Drake RE, et al: Substance abuse in schizophrenia: service utilization and costs. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 181:227–232, 1993Google Scholar

48. Drake RE, Osher FC, Wallach MA: Alcohol use and abuse in schizophrenia: a prospective community study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 177:408–414, 1989Google Scholar

49. Osher FC, Drake RE, Noordsy DL, et al: Correlates and outcomes of alcohol use disorder among rural outpatients with schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 55:109–113, 1994Google Scholar

50. Dackis CA, Gold MS: Psychiatric hospitals for treatment of dual diagnosis, in Substance Abuse: A Comprehensive Textbook. Edited by Lowinson JH, Millman RM. Baltimore, Williams and Wilkins, 1992Google Scholar

51. McLellan AT: Psychiatric severity as a predictor of outcome from substance abuse treatments, in Psychopathology and Addictive Disorders. Edited by Meyer RE. New York, Guilford, 1986Google Scholar

52. Draine J, Solomon P, Meyerson A: Predictors of reincarceration among patients who received psychiatric services in jail. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:163–167, 1994Google Scholar

53. Edens JF, Peters RH, Hills HA: Treating prison inmates with co-occurring disorders: an integrative review of existing programs. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 15:439–457, 1997Google Scholar

54. Strategies for Developing Treatment Programs for People With Co-Occurring Substance Abuse and Mental Disorders. Pub no 3782. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2003Google Scholar

55. Ziedonis DM, Stern R: Dual recovery therapy for schizophrenia and substance abuse. Psychiatric Annals 31:255–264, 2001Google Scholar

56. Drake RE, Mueser KT: Psychosocial approaches to dual diagnosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:105–118, 2000Google Scholar

57. Smelson DA, Losonczy M, Castles-Fonseca K, et al: Preliminary outcomes from a community linkage intervention for individuals with co-occurring substance abuse and serious mental illness. Journal of Dual Diagnosis 1:47–59, 2005Google Scholar

58. Ziedonis DM, D'Avanzo K: Schizophrenia and substance abuse, in Dual Diagnosis and Treatment. Edited by Dranzler HR, Rounsaville BJ. New York, Marcel Dekker, 1998Google Scholar

59. Twamley EW, Jeste DV, Bellack AS: A review of cognitive training in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 29:359–382, 2003Google Scholar

60. Drake RE, Wallach MA, Alverson HS, et al: Psychosocial aspects of substance abuse by clients with severe mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 190:100–106, 2002Google Scholar

61. Minkoff K: An integrated treatment model for dual diagnosis of psychosis and addiction. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:1031–1036, 1989Google Scholar

62. Roberts LJ, Shaner A, Eckman TA: Overcoming Addictions: Skills Training for People With Schizophrenia. New York, Norton, 1999Google Scholar

63. Van Der Gaag M, Snijders TAB: The resource generator: social capital quantification with concrete items. Social Networks 27:1–29, 2005Google Scholar

64. Portes A: Social capital: its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual Review of Sociology 24:1–24, 1998Google Scholar

65. Sampson R, Laub J: Crime in the Making: Pathways and Turning Points Through Life. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1993Google Scholar

66. Gephart MA: Neighborhoods and communities and contexts for development, in Neighborhood Poverty, Vol 1: Context and Consequences for Children. Edited by Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ, Aber JL. New York, Russell Sage Foundation, 1997Google Scholar

67. Freudenberg N, Galea S, Vlahov D: Beyond urban penalty and urban sprawl: back to living conditions as the focus of urban health. Journal of Community Health 30:1–11, 2005Google Scholar

68. Freudenberg N, Daniels J, Crum M, et al: Coming home from jail: the social and health consequences of community reentry for women, male adolescents, and their families and communities. American Journal of Public Health 95:1725–1736, 2005Google Scholar

69. Cosden M, Ellens J, Schnell J, et al: Efficacy of a mental health treatment court with assertive community treatment. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 23:199–214, 2005Google Scholar

70. Cosden M, Ellens J, Schnell J, et al: Evaluation of a mental health treatment court with assertive community treatment. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 21:415–427, 2003Google Scholar