Recovery From Schizophrenia: A Concept in Search of Research

With the emergence of evidence-based pharmacotherapy and psychosocial services for schizophrenia, optimal symptom and functional outcomes are now more readily available to practitioners and consumers (1). To what extent do these advances in treatment and rehabilitation presage recovery from schizophrenia as a realistic goal for the 21st century? In this article we distinguish the process of recovering from recovery as an outcome, summarize the feasibility of recovery as a therapeutic goal, provide an operational definition of recovery to facilitate research on this topic, assemble recent findings that reflect the validity of symptomatic remission and normative functioning in defining recovery, identify factors that may impede or promote recovery, and generate hypotheses that may have heuristic value in a research agenda on recovery from schizophrenia.

Recovery as a process

Just as there are clear differences between recovering from alcoholism or drug addiction and having a sustained recovery with long-term abstinence and normal psychosocial functioning, the same holds for recovery from schizophrenia. Many consumers and professionals have confounded recovering with recovery by failing to grasp this distinction. The processes and stages of recovering are preparations for recovery. Characterized by a reliable, normative definition, recovery is an outcome of the process of recovering. Individuals can take many pathways to recovery depending on the varied factors that influence the process, such as personal attributes, social environment, continuity and quality of treatment, and subjective experiences.

Examples of attributes and experiences that may be associated with individuals who are progressing toward recovery include hope, destigmatization, empowerment, self-acceptance, insight, awareness, collaboration with professionals, sense of autonomy and self-control, and participation in self-help and consumer-run programs. Subjective experiences and attributes not only can mediate the process leading to recovery but also can sustain recovery. For example, a treatment or self-help program may engender a feeling of empowerment, which can be instrumental in motivating a person to sustain treatment and rehabilitation until the criteria used to define recovery have been achieved. Once recovery has been achieved, empowerment may be even more firmly experienced through independence, employment, and freedom from psychosis.

Similarly, having hope for future improvements in quality of life may be reinforced by the enthusiasm and collaborative alliance embedded in a therapeutic relationship. Many consumers who have written first-person accounts of their recovery have pointed to the importance of a long-term relationship with a practitioner who refused to give up hope for the patient's ultimate improvement and recovery (2). Hope can serve to fuel motivation for change and for active participation in clinical services or self-help, which are stepping-stones toward recovery (3). Subjective experiences of empowerment and hope continue to grow after a state of recovery is attained, contributing to further strengthening and protection of individuals from stress-induced relapse. From a research perspective, the processes that are involved in recovering from schizophrenia may be studied as mediating and moderating variables that can facilitate and explain the process of recovery.

Recovery from symptomatic exacerbation or relapse

A major hurdle to the design of empirical studies of recovery is the variability in the clinical course of schizophrenia, which leads to persons' moving into and out of recovery. Individuals' entry and exit into the states of recovery are found in other biomedical disorders, in which additional or new treatments are required to regain recovery status. For example, individuals may have more than one recurrence or episode of cancer, each of which can interrupt a person's meeting recovery criteria. If the recurrence is effectively treated so that remission is again attained for the requisite period and the patient returns to a normal level, the patient's recovery can be said to have been regained.

In a similar fashion, individuals dependent on alcohol or illicit drugs may remain abstinent for varying periods before having one or more relapses. Although addicts can start the process of recovering when restarting a period of sobriety, the use of an operational definition of recovery requires them to remain abstinent for a defined period and to function with a "clean and sober," normal lifestyle.

How might one distinguish recovery from an episode of illness from recovery from the disorder itself? Disorders such as addictions and schizophrenia are defined as episodic in their course; thus a sufficiently long period of symptom remission and normal functioning would qualify as recovery from an episodic exacerbation of schizophrenia and recovery from the disorder. If the operational criteria are met, recovery from an episode is tantamount to recovery from schizophrenia.

Reaching a state of recovery from any biomedical disorder requires only that a sufficiently long period has passed during which the individual's symptoms have been below a pathological threshold of severity and that the person is functioning within broadly defined normal limits. For many carcinomas, the temporal consensus for recovery has been five years without a recurrence. Although our definition of recovery from schizophrenia requires a two-year period of sustained remission and normal functioning, we do not wish to reify any particular tenure as essential for recovery. Some evidence supports a two-year interval of normalization for the time criterion in defining recovery from schizophrenia. The American Psychiatric Association's (APA's) Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Schizophrenia delineates phases of response to treatment as taking between one and two years for progression from the florid and acute phases, through the stabilization and stable phases, to the recovery phase (4). If the return of normal functioning takes approximately two years after a relapse, two continuous years of sustained remission of symptoms and normal functioning reflects an empirically convincing period that demonstrates stability (5).

Persons who have recovered from schizophrenia would be expected to occasionally relapse, resulting in temporary loss of the status of recovery because of substance abuse, which is a common co-occurring disorder; stressors that overwhelm coping and social skills; and medication noncompliance. Having a time interval that is integral to the criteria for recovery is essential for empirical studies that attempt to categorically define recovery.

There are alternative ways to define recovery other than through categorical outcome domains. For example, a dimensional approach in which degrees or extent of recovery could be developed by researchers, clinicians, and consumers. From this point of view, a multidimensional set of continua could define various approximations to recovery, reflecting "substantial clinical and psychosocial improvement." By using a more flexible, dimensional definition of recovery within a range of outcomes, including differing durations of substantial clinical and psychosocial improvement, debates and invidious comparisons of recovery rates by clinicians, researchers, and consumers could be mitigated. In contrast with a categorical approach, a dimensional definition of recovery would enable quantitative ratings to be made on the criterion variables so that degrees of recovery could be determined.

Evidence for pursuing a research agenda on recovery

During our four decades of treatment research and clinical experiences with clients with schizophrenia, we repeatedly noted that a surprising number reached outcomes marked by sustained symptom remissions and relatively normal psychosocial functioning. These observations led us to study more closely and operationally the outcome domains and influences that were associated with the patients' substantial and durable improvements. The emerging consensus in longitudinal studies of schizophrenia also indicates similar types of positive outcomes. From a different source, the recent emphasis on recovery by consumers, advocates, and mental health professionals added impetus to our interest in recovery as a reachable state. In line with this zetigeist of recovery is the recent report of the President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health (6).

To place the goal of recovery in clinical perspective, a "complete return to premorbid levels of functioning" (7) or a "complete return to full functioning" (8), as defined by the DSM, are inadequate criteria for defining recovery. Sustained symptom remission is not included in these criteria and the term "full functioning" is ambiguous and impossible to measure. Because the onset of schizophrenia during adolescence or early adulthood occurs before individuals can attain social, occupational, and independent functioning, returning to premorbid levels of functioning is often below the threshold of what would be considered within the normal range of psychosocial performance for mature adults. In addition, the general term "complete return to full functioning" is incompatible with the variability in how society defines normal psychosocial functioning.

Failure to adopt a socially valid construct of recovery has led to several adverse consequences. Because of the current official nosology of schizophrenia, it is not surprising that most clinicians, patients, and families so readily resign themselves to the belief that individuals with this disorder are doomed to a lifetime of disability, with few expectations for satisfying relationships and productive involvement in society. Professional, consumer, and public pessimism and stigma associated with schizophrenia are further harmful consequences of the failure to place recovery on our collective radar screen. At a practical level, therapeutic nihilism, negative stereotyping, and stigma operate as a self-fulfilling prophecy, because consumers may react to these attributions by denying their illness and need for treatment, which all too often leads to poor outcomes.

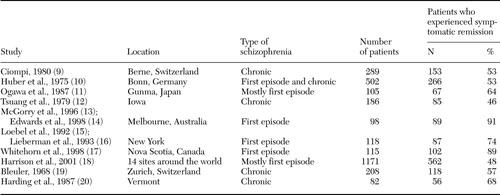

But the truth about schizophrenia lies elsewhere. A growing body of empirically based, clinical research shows that recovery can occur. As summarized in Table 1, data from several clinical research centers have demonstrated a high rate of symptomatic remission in recent onset and chronic schizophrenia (9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20). For instance, using a well-crafted, multidimensional definition of recovery from schizophrenia, Harding and collaborators (20) showed that more than half the individuals with this diagnosis were able to live satisfying, productive lives unencumbered by continuous and disabling psychotic symptoms. This research group documented that recovery among carefully and conservatively diagnosed persons with schizophrenia could be characterized by measures of work, community functioning, subjective quality of life, hospitalizations, and symptoms. Of the 262 individuals in their study, 48 to 68 percent met criteria for the various dimensions of recovery.

A key element in these favorable long-term outcomes was access to continuous and reasonably comprehensive mental health services. To highlight the importance to recovery of continuous, comprehensive, community-based, and coordinated services, comparison of long-term outcomes of schizophrenia in the states of Vermont and Maine is instructive. In the early 1960s Vermont established a system of accessible community-based treatment that was flexibly linked to the needs of its patients with chronic mental illness. The state of Maine did not. Patients from both states were matched during their early state hospital treatment on age, education, sociodemographic factors, and duration and severity of illness. The rate of recovery was twice as high in Vermont as in Maine (21).

New, evidence-based treatments for schizophrenia have also contributed to a more optimistic prognosis for the disorder. The advent of second-generation antipsychotics, although plagued with their own profile of side effects, offers a wider choice of effective medications that are better tolerated by patients and are thereby associated with more sustained adherence to prescribed drug regimens (22). Because of the heterogeneity of schizophrenia and individual differences in therapeutic response to any one antipsychotic drug, patients who have been suboptimally responsive to certain first-generation drugs may respond favorably to a new antipsychotic drug. This finding was most dramatically seen with the introduction of clozapine. The drug yielded substantial symptomatic benefits for almost half the patients who had been resistant to treatment and had chronic forms of schizophrenia. In addition, four evidence-based psychosocial treatments have been introduced that raise the likelihood of improved psychosocial functioning and reduced relapse: assertive community treatment, family psychoeducation, supported employment, and social skills training (23).

Conceptual foundation for a definition of recovery

Just as with other biomedical disorders—such as diabetes, coronary artery disease, and cancer—empirically based, quantitative studies of recovery from schizophrenia should be designed from operational definitions of recovery. One of the prime criteria for operational definitions is the level, frequency, and duration of symptoms. With the exception of infections, most serious disorders are marked by episodes of symptomatic relapse or exacerbation that reflect worsening of the underlying pathophysiology. In diabetes, changes in insulin secretion, blood level, and binding to receptors may account for increases in the symptoms of the illness. With atherosclerotic coronary artery disease, narrowing and blockage of one or more of the coronary arteries leads to angina or the symptoms of an infarction. The signs and symptoms of growth or metastasis reflect worsening of the pathology of the cancer. Although we do not know the underlying pathophysiology of schizophrenia, its signs and symptoms serve as a proxy for worsening of the abnormal neural processes.

Thus, when building a construct of recovery from schizophrenia, it is presumed that a key dimension in a definition of the construct must be the waxing and waning of schizophrenia's key positive and negative symptoms. By adding an appropriate period of remission and a substantial reduction of symptoms into the construct, the rate of recovery from illness may be measured. If some suitable and professionally agreed on duration of remission of signs and symptoms of the disorder can be reached, it may be possible to develop a credible criterion for recovery. In cancer, the duration of remission of signs and symptoms is often five years. Given the lack of research on the durability of remitted symptoms in schizophrenia, any period used for defining recovery is somewhat arbitrary. In our work we have achieved a provisional, categorical definition of recovery that can be seen as a starting point for generating research on this topic.

But symptom remission alone is inadequate for a definition of recovery from schizophrenia, just as it would be for diabetes and coronary artery disease. Dimensions of improved psychosocial functioning must also be integral to a definition of recovery. As noted below, these dimensions include work, school, family life, friends, recreation, and independent living. These dimensions also will require consensus among practitioners, researchers, patients, and family members in operationalizing levels of functioning that would be consistent with a definition of recovery. Consensual agreement among stakeholders about the operationalized and criterion-based definition for each relevant dimension is sometimes referred to as social or professional validation. In response to our call for validation of an operational construct of recovery (24), a consensus statement by schizophrenia researchers recently presented their definition of symptomatic recovery: on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, no psychotic symptom above 3 (mild) during a consecutive period of six months (25).

Summary of research

A dual work plan guided our development of a research agenda on recovery from schizophrenia. First, we identified colleagues in the United States, Canada, and Europe who were currently engaged in research on recovery and had formulated and published an operationalized definition of recovery as an outcome state. We invited each of them to collaborate with us in sharing methods and results. Second, we organized the contributions from each of the collaborating investigators and sites into a stepwise approach, first considering the dimensions that might be important in a definition of recovery, followed by distinguishing the process of "recovering" from the outcome state of "recovery," and then proceeding to an operational definition of recovery with construct, social, and discriminant validation.

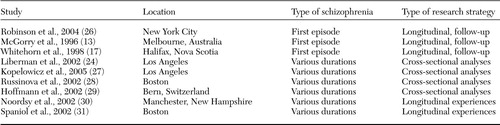

A search of the literature led to the identification of nine additional research groups that were pursuing studies on recovery from schizophrenia, representing a cross-section of geographic locations, research strategies, populations, and areas studied (13,17,24,26,27,28,29,30,31). Individuals with differing durations of schizophrenia and disability were included in the study samples, and studies defined recovery in different ways. Research included cross-sectional and longitudinal studies.

As shown in Table 2, five studies used longitudinal, follow-up designs to determine the extent to which a defined treatment program yielded sustained remission of symptoms that was associated with psychosocial functioning within the normal range. Two of the studies were with individuals who were in the early period of their disorder, and one used a cohort of patients who were ill for varying periods. Cross-sectional studies of individuals who reached operationalized definitions of recovery are also listed in Table 2. In these three cross-sectional studies, clients had varying durations of illnesses and the definitions of recovery ranged in their degree of comprehensiveness. Two of the studies focused primarily, but not exclusively, on the recovery process, developing constructs to depict important attributes of clients' subjective experiences and personal development presumed to foster recovery.

Definition of recovery

Dimensions for defining recovery

Without reliable measurement, science cannot advance. This observation applies to the construct of recovery as well as to any other aspect of psychiatry or medicine. Just as advances in etiology and treatment followed the operational definition of diagnostic categories with DSM-III, we can expect progress in understanding the factors that impede or promote recovery when this construct is defined in measurable terms. What then are the appropriate dimensions that should be used in a definition of recovery?

Symptom remission alone is inadequate to define recovery from schizophrenia as we have seen in efforts to demarcate recovery from depression (32). Even when symptoms of mood or anxiety disorders are in complete remission, psychosocial functioning may continue to be impaired (33,34). For example, in one study of 219 patients with psychotic affective disorders, although 98 percent achieved symptomatic recovery by 24 months, only 38 percent achieved functional recovery (34). Similarly, individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder whose symptoms were effectively treated with medication and cognitive-behavior therapy continued to exhibit residual disability and had poor quality of life (35). In each of these psychiatric disorders, the absence of symptoms is not a proxy for a return to wellness. Therefore, a definition of recovery from any serious mental illness should include participation in work or school and in social, family, and recreational activities as well as achieving symptom remission.

Because schizophrenia is so often associated with dependence on professionals, agencies, families, and other caregivers, recovery should include a dimension related to independent functioning. In other words, independent functioning would include being productive in work or school, social relations, family life, and recreational activities. One major aspect of this domain is the ability to take care of one's personal needs without assistance. Whether or not the individual is living apart from the family—which could be influenced by cultural and financial factors—independent functioning could be defined as managing one's own medication, health, and money without regular supervision. Thus persons who have a representative payee or whose medications are administered to them would not meet this criterion for recovery. Similarly, large-scale dependence on families, professionals, and systems of mental health and human services for social and recreational activities—as in long-term participation in psychosocial clubs or day treatment programs—would be inconsistent with a fully normative definition of recovery.

A definition of recovery from schizophrenia is not the same as a cure. Individuals can recover and live reasonably normal and full lives even though they are vulnerable to relapse and must be treated indefinitely. In fact, for most individuals with schizophrenia, the control of symptoms and satisfactory and independent engagement in psychosocial pursuits will require their participation in comprehensive, coordinated, competent, and consumer-oriented flexible levels of services. Support for the role in recovery for evidence-based, comprehensive treatment comes from a study of 825 persons with schizophrenia (36). Attitudes of patients with schizophrenia that were consistent with an orientation toward recovery were significantly and positively related to participation in family psychoeducation and optimal pharmacotherapy. The findings also suggested that recovery might be facilitated by treatments that reduce depression and other psychiatric symptoms while minimizing medication side effects.

Operational definition of recovery

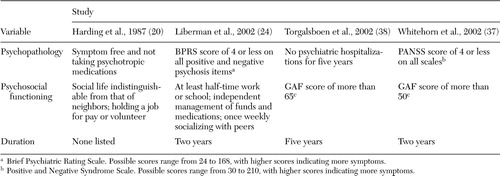

Although there are no consensually validated criteria for defining recovery from schizophrenia, in Table 3 we list four published sets of criteria to encourage others to propose alternatives. The dimensions in the four definitions of recovery have several similarities. First, because the diagnosis of schizophrenia relies on meeting of symptom criteria of clinical significance, each of the studies defined recovery as having some degree of symptomatic stabilization.

Liberman and colleagues (24) required scores on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) below what would correspond with criteria for the diagnosis of schizophrenia. For example, a score of 4, moderate, on the symptom "unusual thought content" includes strange ideas that either are not strongly held or do not disrupt psychosocial functioning; a score of 3, mild, or 2, very mild, on this symptom is at the level of ideas of reference or persecution and considered not delusional. For the negative symptom "emotional withdrawal" a score of 4, 3, or 2 is operationalized as "shows some affect appropriate to the topic of conversation" or "tends not to show spontaneous emotional involvement with interviewer but responds when approached and engaged in conversation." The cutoff points on the BPRS for symptoms being present but not of psychotic proportions avoids the pitfall of establishing unrealistically demanding criteria for recovery at the symptomatic level.

Because the diagnosis of schizophrenia also requires markedly impaired functioning in work, school, interpersonal relations, or self-care, areas of functional criteria are also included in each definition of recovery. For example, Whitehorn and colleagues (37) proposed a definition of recovery that included autonomous daily living (that is, a Global Assessment of Functioning score greater than 50) and social and occupational functioning within the normal range (that is, a Social and Occupational Functional Assessment score greater than 60). Similarly, Torgalsboen and Rund (38) defined recovery as psychosocial functioning within the normal range (that is, a Global Assessment of Functioning score greater than 65). Finally, three of the criteria sets include a specific duration of symptomatic and functional stability. At least two consecutive years of maintenance at or above the threshold levels was suggested, most likely because few randomized controlled trials of treatment extend beyond two years and because two years is long enough for clinical improvements to be solidified and translated into significant changes in objective and subjective quality of life.

Criteria for determining recovery conceivably could be drawn from any number of domains and could be either categorical or dimensional in nature. In fact, a multidimensional definition, which consists of continua, might be preferable at this stage. Correlational and experimental research that considers factors related to the various dimensions could then determine empirically the optimum thresholds or cutoff points for selecting a categorical definition.

Several of the collaborating research teams independently have included measures of psychosocial functioning in their definitions of recovery. For example, the New Hampshire group (30) recommended use of the Social Functioning Scale (39), the Social Adjustment Scale-II (40), or the Independent Living Skills Survey (41) to measure their category of "getting on with life." Threshold levels on these scales could be established as criteria for categorical purposes in defining recovery; alternatively, the ratings on one or another of these scales could be used to describe "degree of recovery" on a continuum.

The Boston University research group (28) highlighted the relevance of employment in a definition of recovery. By using a national sample of 109 employed individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum disorders, the study found that 75 percent of the clients had uninterrupted employment for two years and that the rest had sustained employment for at least one year.

Validity of the proposed definition

A variety of international studies (24,26,28,37,38,42,43) that used different research strategies to generate data have provided construct and social validation for the definition of recovery proposed by Liberman and colleagues (24), which is listed in Table 3. In addition, we conducted structured interviews with a group of 55 persons—consumers, family members, mental health professionals, and paraprofessionals—all of whom were engaged in schizophrenia treatment (42). Three-fourths of the respondents endorsed the criterion related to living independently, two-thirds endorsed the criterion related to social and recreational activities and school and work, and one-half endorsed the criterion for remission of psychotic symptoms. Moreover, discriminant validity of the operational definition proposed by Liberman and colleagues (24) came from studies that identified factors that differentiate recovered from nonrecovered persons with schizophrenia (26,27) and highlighted how these factors, when targeted for treatment, reliably yield better outcomes (44,45,46,47,48,49).

Predictive validity of the operational definition of recovery that was proposed by Liberman and colleagues (24) was tested in a study that followed 118 young persons who experienced their first episode of schizophrenia for five years (26). The cumulative proportion of patients who met the criteria for recovery for two years or longer varied according to the duration of follow-up: at three years, 9.7 percent met criteria; at four years, 12.3 percent met criteria; and at five years, 13.7 percent met criteria. It should be noted in construing these relatively low rates of recovery that in this study the treatment was limited to pharmacotherapy and standard case management. The investigators also found that better cognitive functioning, shorter duration of psychosis before study entry, and more normal cerebral asymmetry were associated with recovery.

Discussion

Distinguishing "recovering" from "recovery" in schizophrenia with operational criteria for both may promote greater clarity and empirical research on the construct of recovery. In the current literature and professional parlance, recovery has been associated with as many meanings as there are proponents of this term. It is time to move the construct to a researchable concept with broad and credible consensual validation. As with other diseases, when rates of recovery are reported in replicable, reliable, and valid terms, stigma is decreased (50). This result is likely to ensue because one major contributor to stigma is the hopelessness and poor prognosis attached to any disorder.

With the acceptance of operational modes of defining recovery, empirical research could proceed to identify the extent of recovery that can be achieved with different types and amounts of treatment for patients with various characteristics. Studies of content, social, construct, concurrent, and predictive validity would enable researchers to design and test the relevance and applicability of various definitions. A variety of criterion-referenced definitions will help move the important goal of recovery into the mainstream of psychiatric research.

Social validation of the construct of recovery can be studied by submitting various operational definitions of recovery to groups of clinicians, patients, consumer activists, family members, advocates, researchers, and even laypersons. Social validity refers to the endorsement and acceptance of the operational definitions of recovery by a wide range of individuals whose values are congruent with prevailing social norms, standards, and expectations. Thus, because definitions of recovery should be consistent with normative behavior, dimensions that are within the range of what most people would consider as "within normal limits" provide social validity to the construct. For example, in today's harsh employment climate, working half-time might be considered by most people to be within normal limits. Social validity also refers to the functional utility or benefits of a particular behavior. It can be readily agreed that managing one's own finances and health needs in a reliable and organized manner will bring positive consequences to the individual.

Without methodologically solid social validation, the construct of recovery will suffer from lack of credibility. For other constructs and treatment outcomes, this type of validation has been done effectively with carefully selected focus groups, concept mapping, surveys, and consensus conferences. The last-named mode of validation has been used extensively in APA's treatment guidelines, which have been produced by expert committees after thorough reviews of the literature (4).

Studies of the predictive validity of factors that appear to influence recovery as an outcome can be conducted through longitudinal, follow-up designs. Although still controversial, a large number of follow-up studies have found shorter durations of untreated psychosis to be a predictor of recovery (51). One recently published longitudinal study found that lack of social support and the receipt of disability benefits predicted reduced employment and a lower rate of marriage at the time of follow-up (52).

The duration of treatment continuity has been noted to be associated with recovery. For example, in a 15-year follow-up study of persons with schizophrenia, patients in treatment for two years or less were only one-third as likely to meet recovery criteria as patients who were in continuous treatment for 15 years (unpublished manuscript, Harrow M, Grossman L, Jobe TH, 2004). In the same study, the coping and problem-solving skills of patients, an index of their resiliency, was found to be one of the most robust predictors of long-term recovery. Longitudinal research could answer the question, If early intervention is provided at times of the prodromal signs of schizophrenia, does such treatment improve the prospects for longer-term recovery with its ability to mitigate or eliminate the full-blown psychosis? Do individuals with access to evidence-based treatments—such as assertive community treatment, social skills training, and supported employment—have a greater likelihood of attaining recovery than those who live in areas where similar amounts of service, but not empirically validated services, are available?

Other factors that deserve consideration for studies of predictive validity include premorbid and postmorbid social functioning, family relationships, substance abuse, neurocognitive capacities, and structural and functional integrity of the brain. Research may reveal these dimensions as mediating or moderating variables in achieving a recovered state. For example, we have found enduring patterns of neurocognition to differentiate recovered from nonrecovered patients (27). Recent treatment studies have shown that by enhancing neurocognition, significant improvements are found in the social and occupational functioning of persons with schizophrenia (47,48). Predictive validity can also be assessed through long-term correlational studies using epochal data. For example, Warner (53) identified a significant relationship between the strength of the national economy and the proportion of individuals who recovered from schizophrenia.

Intervention studies can also make important contributions to knowledge of the factors related to recovery. For example, a study might include independent, socioenvironmental, behavioral, and symptomatic variables that are malleable and hypothesized to influence likelihood of recovery. By targeting dependent variables that are presumed to be linked to recovery, such as family support and neurocognitive capacity, interventions that are effective in improving their targeted goal and that increase the proportion of patients who meet recovery criteria contribute evidence to validate those dependent variables as being germane to recovery. There are many other types of research in which interventions that strengthen malleable predictor variables can provide evidence, either for or against, the validity of factors that were targeted for intervention.

Conclusions

Clearly, it is not easy to separate "process" from "outcome" in delineating recovery from schizophrenia, as the elements in these two perspectives are constantly reverberating with each other. Nor is it easy or useful to make fine distinctions between objective and subjective factors in recovery, because these are always in dynamic interaction with one another. Most, if not all, of the subjective attributes of recovering from schizophrenia are influenced by the progress being made by individuals as they work toward recovery. Thus the greater the person's symptomatic and functional improvement, the more one would expect subjectively experienced qualities such as hope, empowerment, self-responsibility, and autonomy to be in evidence. The process of recovering and recovery as an outcome are in apposition, not opposition.

The authors are affiliated with the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Kopelowicz is also with the San Fernando Mental Health Center in Granada Hills, California. Send correspondence to Dr. Kopelowicz at 10605 Balboa Boulevard, Suite 100, Granada Hills, California 91344 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Empirically based research on recovery from schizophrenia

|

Table 2. Overview of studies and research teams investigating the construct of recovery

|

Table 3. Published criteria for recovery from schizophrenia

1. Kopelowicz A, Liberman RP: Integrating treatment with rehabilitation for persons with major mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services 54:1491–1498,2003Link, Google Scholar

2. Geller JL: First-person accounts in the journal's second 25 years. Psychiatric Services 51:713–716,2000Link, Google Scholar

3. Deegan PE: Recovery: the lived experience of rehabilitation. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 11:11–19,1996Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. American Journal of Psychiatry 161(suppl 2):S1-S56, 2004Google Scholar

5. Sullivan G, Marder SR, Liberman RP, et al: Social skills and relapse history in outpatient schizophrenics. Psychiatry 53:340–345,1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health: Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2006. Available at www.mentalhealthcommission.govGoogle Scholar

7. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1980Google Scholar

8. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

9. Ciompi L: Catamnestic long-term study on the course of life and aging of schizophrenics. Schizophrenia Bulletin 6:606–618,1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Huber G, Gross G, Schuttler R: A long-term follow-up study of schizophrenia: psychiatric course of illness and prognosis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 52:49–57,1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Ogawa K, Miya M, Watarai A, et al: A long-term follow-up study of schizophrenia in Japan with special reference to the course of social adjustment. British Journal of Psychiatry 151:758–765,1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Tsuang M, Woolson RF, Fleming J: Long-term outcome of major psychoses: I. Schizophrenia and affective disorders compared with psychiatrically symptom-free surgical conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry 36:1295–1301,1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. McGorry PD, Edwards J, Mihalopoulos C, et al: EPPIC: an evolving system of early detection and optimal management. Schizophrenia Bulletin 22:305–326,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Edwards J, Maude D, McGorry PD, et al: Prolonged recovery in first-episode psychosis. British Journal of Psychiatry 172 (suppl 33):107–116,1998Google Scholar

15. Loebel AD, Lieberman JA, Alvir JMJ, et al: Duration of psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:1183–1188,1992Link, Google Scholar

16. Lieberman J, Jody D, Geisler S, et al: Time course and biological correlates of treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:369–376,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Whitehorn D, Lazier L, Kopala L: Psychosocial rehabilitation early after the onset of psychosis. Psychiatric Services 49:1135–1137,1998Link, Google Scholar

18. Harrison G, Hopper K, Craig T, et al: Recovery from psychotic illness: a 15- and 25-year international follow-up study. British Journal of Psychiatry 178:506–517,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Bleuler M: A 23-year longitudinal study of 208 schizophrenics and impressions in regard to the nature of schizophrenia, in The Transmission of Schizophrenia. Edited by Rosenthal D, Kety SS. Oxford, Pergamon, 1968Google Scholar

20. Harding CM, Brooks GW, Ashikaga T, et al: The Vermont longitudinal study of persons with severe mental illness: II. Long-term outcome of subjects who retrospectively met DSM-III criteria for schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 144:727–735,1987Link, Google Scholar

21. DeSisto MJ, Harding CM, McCormick RV, et al: The Maine and Vermont three-decade studies of serious mental illness. II. Longitudinal course comparisons. British Journal of Psychiatry 167:338–342,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Csernansky JG, Mahmoud R, Brenner R: A comparison of risperidone and haloperidol for the prevention of relapse in patients with schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine 346:16–22,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A, Silverstein SM: Psychiatric rehabilitation, in Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. Edited by Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, Md, 2005Google Scholar

24. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A, Ventura J, et al: Operational criteria and factors related to recovery from schizophrenia. International Review of Psychiatry 14:256–272,2002Crossref, Google Scholar

25. Andreasen NC, Carpenter WT, Kane JM, et al: Remission in schizophrenia: proposed criteria and rationale for consensus. American Journal of Psychiatry 162:441–449,2005Link, Google Scholar

26. Robinson DG, Woerner MG, McMeniman M, et al: Symptomatic and functional recovery from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:473–479,2004Link, Google Scholar

27. Kopelowicz A, Ventura JV, Liberman RP, et al: Neurocognitive correlates of recovery. Psychological Medicine, in pressGoogle Scholar

28. Russinova Z, Wewiorski NJ, Lyass A, et al: Correlates of vocational recovery for persons with schizophrenia. International Review of Psychiatry 14:303–311,2002Crossref, Google Scholar

29. Hoffman H, Kupper Z: Facilitators of psychosocial recovery from schizophrenia. International Review of Psychiatry 14:293–302,2002Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Noordsy D, Torrey W, Mueser K, et al: Recovery from severe mental illness: an intrapersonal and functional outcome definition. International Review of Psychiatry 14:318–326,2002Crossref, Google Scholar

31. Spaniol L, Wewiorski NJ, Gagne C, Anthony WA: The process of recovery from schizophrenia. International Review of Psychiatry 14:327–336,2002Crossref, Google Scholar

32. Frank E, Prien RF, Jarrett RB, et al: Conceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder: remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:851–855,1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Bystritsky A, Liberman RP, Hwang S, et al: Social functioning and quality of life comparisons between obsessive-compulsive and schizophrenic disorders. Depression and Anxiety 14:214–218,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Tohen M, Hennen J, Zarate CM, et al: Two year syndromal and functional recovery in 219 cases of first episode major affective disorder with psychotic features. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:220–228,2000Link, Google Scholar

35. Koran LM, Thienemann ML, Davenport R: Quality of life for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:783–788,1996Link, Google Scholar

36. Resnick SG, Rosenheck RA, Lehman AF: An exploratory analysis of correlates of recovery. Psychiatric Services 55:540–547,2004Link, Google Scholar

37. Whitehorn D, Brown J, Richard J, et al: Multiple dimensions of recovery in early psychosis. International Review of Psychiatry 14:273–283,2002Crossref, Google Scholar

38. Torgalsboen AK, Rund BR: Lessons learned from three studies of recovery from schizophrenia. International Review of Psychiatry 14:312–317,2002Crossref, Google Scholar

39. Birchwood M, Smith J, Cochrane R, et al: The Social Functioning Scale: the development and validation of a new scale of social adjustment for use in family intervention programmes with schizophrenic patients. British Journal of Psychiatry 157:853–859,1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Schooler NR, Hogarty GE, Weissman MM, et al: Social Adjustment Scale II, in Resource Materials for Community Mental Health Program Evaluators. Edited by Hargreaves WA, Attkisson CC, Sorenson JE. Washington DC, US Printing Office, 1979Google Scholar

41. Wallace CJ, Liberman RP, Tauber R, et al: The Independent Living Skills Survey: a comprehensive measure of the community functioning of severely and persistently mentally ill individuals. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:631–658,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Kopelowicz A, Liberman RP: Recovery from schizophrenia. Directions in Psychiatry 21:287–305,2001Google Scholar

43. Drake RE, Green AI, Mueser KT, et al: The history of community mental health treatment and rehabilitation for persons with severe mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal 39:427–440,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Hogarty GE, Anderson CM, Reiss DJ, et al: Family education, social skills training, and maintenance chemotherapy in aftercare treatment of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 43:633–642,1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Liberman RP, Wallace CJ, Blackwell G, et al: Innovations in skills training for the seriously mentally ill. Innovations and Research 2:43–60,1993Google Scholar

46. Drake RE, Becker DR: The individual placement and support model of supported employment. Psychiatric Services 47:473–475,1996Link, Google Scholar

47. Van der Gaag M, Kern RS, Van den Bosch RJ, et al: A controlled trial of cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 28:167–176,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Hogarty GE, Flesher S, Ulrich R, et al: Cognitive enhancement therapy for schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:866–876,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Wallace CJ, Tauber R: Supplementing supported employment with workplace skills training. Psychiatric Services 55:513–515,2004Link, Google Scholar

50. Dijker AJ, Koomen W: Extending Weiner's attribution-emotion model of stigmatization of ill persons. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 25:51–68,2003Crossref, Google Scholar

51. Haas GL, Garrett LS, Sweeney JA: Delay to first antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia: impact on symptomatology and clinical course of illness. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 32:151–159,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Agerbo E, Byrne M, Eaton WW, et al: Marital and labor market status in the long run in schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:28–33,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Warner R: Recovery From Schizophrenia: Psychiatry and the Political Economy. New York, Routledge, 1994Google Scholar