Integration of Care: Integrating Treatment With Rehabilitation for Persons With Major Mental Illnesses

Abstract

Psychiatric treatment and rehabilitation are integrated, seamless approaches aimed at restoring persons with major mental disorders to their best possible level of functioning and quality of life. Driven by a thorough assessment, treatment and rehabilitation are keyed to the stage and type of each individual's disorder. Examples of coordinated treatment and rehabilitation are pharmacotherapy, supported employment, social skills training, family psychoeducation, assertive community treatment, and integrated programs for persons with dual diagnoses. The authors conclude by proposing seven principles to guide mental health practitioners in their integration of pharmacologic and psychosocial interventions.

The growing recognition that a large proportion of individuals with psychotic, mood, and anxiety disorders experience a poor quality of life—characterized by long-term disability, persisting symptoms, or a relapsing course of illness—has given birth to the field of psychiatric rehabilitation. Although early intervention and effective treatment of acute episodes of symptom exacerbation are important for minimizing disability, longer term treatment and rehabilitation are almost always essential for obtaining optimal and durable therapeutic outcomes.

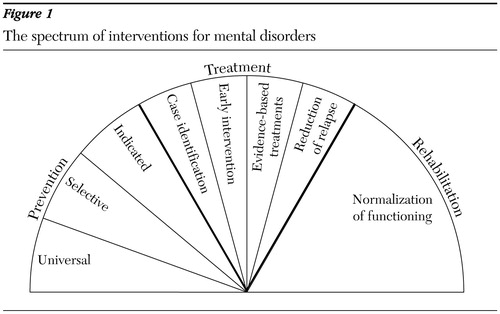

The spectrum of interventions for mental disorders, from prevention to treatment to rehabilitation, is depicted in Figure 1. It should be noted that this spectrum represents a continuum of services and does not imply any artificial typology separating the interventions. Similar types of pharmacologic and psychosocial interventions may be used for universal and selected forms of prevention as are used for treatment and rehabilitation.

Although there are no conceptual or operational differences between "treatment" and "rehabilitation," the two terms have inadvertently been separated, because researchers and practitioners have focused their work in different realms. The terms are conventionally used to refer to interventions that differentiate pharmacologic from psychosocial services, that are relevant for different phases or types and severity of mental disorders, or that focus on different goals or behavioral dimensions. The term "integrating" in the title of this article should be viewed as our effort to "reality test" the mistaken belief that treatment and rehabilitation are different enterprises. Perpetuating this fabrication can only have adverse effects on our efforts to train young mental health professionals and to provide continuous and comprehensive care to our clients.

For example, the term "treatment" is usually used to describe interventions that focus on the amelioration or elimination of symptoms during the acute phase of a disorder that are not usually associated with long-term disability, whereas "rehabilitation" is reserved for interventions that target functional and cognitive disabilities during the stable, recovery, or refractory phases or types of disorders. It is important to grasp the concept that treatment and rehabilitation are seamless approaches to caring for the same human beings who require different interventions for different problems at different points during the course of their disorders.

Treatment and rehabilitation focus on impairments, disabilities, and handicaps of persons with serious mental illness. Impairments are the symptoms and cognitive deficits that reflect the underlying structural and functional pathology of the brain. Disabilities are represented by the difficulties that persons with mental disorders have in social and independent living skills—difficulties that stand in the way of more normal functioning in jobs, school, friendships, family life, recreation, and self-management of illness. Disabilities are caused by impairments, lack of premorbid role functioning, and erosion of skills through years of illness-based disuse. Handicaps are the barriers erected by society to a fuller participation in community life, such as the disincentives for persons with mental illness to work because of the risk of jeopardizing disability benefits and the lack of supported employment, education, and residential services.

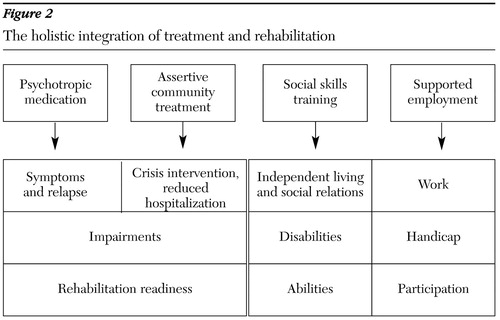

The holistic integration of treatment and rehabilitation is depicted in Figure 2. The various evidence-based treatments that are available to us can be seen as being directed at different problems or goals in the longitudinal clinical enterprise. Efforts to reduce symptoms and relapse are aimed at stabilizing patients who are acutely ill and preparing them to receive the services that can be most effective during the stable phase of their disorder. Services that focus on improving work and social functioning come into play during the stable phase and use interventions that are appropriate for the targeted problems. The ultimate aim of these various treatments is to restore a person who has a major mental disorder to the best level of functioning as possible with as full a participation in the social, work, family, and recreational domains and as little dependence on professional treaters as possible.

Social skills training and supported employment are good examples of the essential integration of different interventions deployed at different phases of disorders for different types of problems. The effectiveness of both these services depends on close liaison and integration of providers with counterparts responsible for pharmacotherapy and crisis intervention. Such integration helps maintain the individual at a sufficiently stable clinical level to enable the skills training and supported employment to have their desired impact on functional roles that permit maximal participation in society.

Many psychiatric disorders are associated with residual and disabling functional and cognitive deficits for which long-term and interconnected drug and psychosocial treatments are required if optimal outcomes are to be attained. For example, psychosocial services are of little value unless the client is adhering to maintenance antipsychotic, mood stabilizer, and antidepressant regimens. Similarly, pharmacotherapy will be of no avail if psychoeducational efforts are not used to inform clients and members of their families about the benefits and side effects of medication and to involve them as partners and active collaborators in the treatment effort.

Major mental disorders and disability

Disability associated with psychiatric disorders extends beyond schizophrenia and its spectrum of psychotic disorders. An increasing body of knowledge has demonstrated that persons with depression and bipolar disorder have considerable disability in social, family, and work functioning, even after their acute episodes have been controlled and their symptoms have been brought into relative remission. For example, the Medical Outcomes Study (1) found that the social functioning of persons with depressive disorders was significantly worse than that of persons with chronic medical conditions, including arthritis, diabetes, and advanced coronary artery disease. Similarly, in an analysis of data from eight major studies of treatment for depression, more than half of the clients with depression were work impaired, including 11 percent who were unemployed. Although symptoms were brought into remission or good control among 60 percent of persons with major depression within eight weeks of the inception of pharmacologic or psychotherapeutic treatment, posttreatment work impairment rates were as high as 75 percent of treated clients (2).

More recent reviews of dozens of well-controlled trials of antidepressant medications have shown that only 40 to 60 percent of individuals respond with a complete remission of their symptoms (3). In one study of more than 580 clients with major depression who were treated in customary clinical practice settings by the American Psychiatric Association Practice Research Network, the vast majority were in treatment for at least two years because of suboptimal response (4). Thus a majority of clients who are treated for major depression continue to meet the diagnostic criterion related to psychosocial functioning, "clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning."

In recent years, the notion that clients with bipolar disorder have good symptomatic as well as psychosocial recoveries between manic and depressive episodes has been controverted by the findings of longitudinal studies underlining the poor interepisode role functioning of these individuals, even after symptoms have gone into remission. Approximately one-third of clients with bipolar disorder experience severe work impairment two years after a hospitalization (5). Only 20 percent of clients with bipolar disorder return to their premorbid level of productivity (6). Even in the absence of symptoms of mood disorder, clients describe apathy, loss of energy, and inadequate motivation to resume work, school, or social activities. Their disabilities pose considerable stress, demoralization, and tension among family members who find themselves—along with professional caregivers—unable to influence recovery of their afflicted relatives (7).

Disability also occurs with several anxiety disorders, both during periods of symptom exacerbation and during periods in which symptoms are controlled by medications or evidence-based psychotherapies. Posttraumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder are examples of anxiety disorders whose sufferers continue to exhibit significant decrements in functioning both before and after treatment.

For example, 31 ambulatory care clients with obsessive-compulsive disorder who were being treated with intensive cognitive-behavioral therapy and medication exhibited a much lower than normal quality of life both before and after treatment, even when treatment was successful in eliminating or ameliorating the symptoms. When they were compared with a group of 68 persons with schizophrenia who were also in day treatment, the clients with obsessive-compulsive disorder showed just as much disability in a range of domains (8).

Integration for physical problems

Integration of treatment and rehabilitation is not unique to psychiatric practice. For example, physiatrists—in league with cardiologists, physical therapists, and trainers—collaborate as an interdisciplinary team to treat and rehabilitate persons who have had myocardial infarctions or open-heart surgery. Communicating and consulting with one another, the team members develop and implement a comprehensive program for putting the pieces of a person's life back together. Their joint efforts are to generate improvements at the medical, behavioral, social, emotional, and occupational levels. Other medical problems—for example, stroke, spinal cord transection, and diabetes—also require that various medical specialists work together as a team throughout the course of chronic illness to reduce disability and restore optimal functioning. For all medical and psychiatric conditions, the only consequence of separation and lack of integration among members of the treatment team is poor outcomes.

Improving symptoms through integration

Several factors have spurred clinical interest and research studies of psychiatric rehabilitation for persons with major mental disorders. For example, the initiation of therapeutic drugs to quell an acute episode of illness requires companion psychosocial strategies to ensure engagement and adherence (9). In addition, motivating clients to pursue pharmacotherapeutic or psychosocial treatments requires interventions that connect the client's personal goals with services to be rendered (9). It has also been demonstrated that interepisode disability requires treatment beyond continuation medication (9). Finally, long-term recovery requires comprehensive, coordinated, consistent, competent, compassionate, and consumer-oriented treatments for improving the delivery and outcomes of pharmacotherapy and psychosocial treatments (9).

Multidimensional integration by stage or type of disorder

Helping acutely ill individuals define their desired life roles can be a vehicle for engaging them and motivating them to participate in treatment and rehabilitation. In addition, clients who actively participate in goal setting are more likely to abandon denial of their illness. Successful engagement of clients requires a nonjudgmental and nonauthoritarian approach, and even toleration of clients' nonadherence to medication for a certain period.

Inpatient treatment for persons with serious and persistent mental illness should be seamlessly integrated with community services so that hospitalization is brief and minimally disruptive and so that posthospital rehabilitation services provided in the community can be implemented as quickly as possible. Unfortunately, this ideal is often not achieved, and many psychiatric inpatients do not follow through with community care after discharge. Often, the result is a cycle of relapse and rehospitalization—the so-called revolving door phenomenon. Efforts to alter mental health service systems to make them more continuous and accessible, such as the Program for Assertive Community Treatment, have met with considerable success in reducing recidivism, but model programs have not been widely adopted and are unavailable to a majority of clients who might benefit.

The community reentry program—a 16-session modularized skills training program—was designed to teach inpatients how to be active collaborators with the mental health system in creating and then following through with their own tailor-made aftercare plans. Once engaged in this fashion, clients might acknowledge the need for continuing care and become active participants in treatment, discharge, and rehabilitation planning. Studies at New York Hospital—Cornell Medical Center and at the University of California, Los Angeles, have shown that inpatients with schizophrenia who participated in this program improved their knowledge and performance of the skills presented in the program, had significantly higher rates of engagement with aftercare services after discharge, and improved their community functioning after discharge (10,11).

Interventions should be integrated so that clients can move along the pathway from acute and florid exacerbation of psychopathology through the stabilization, stability, and recovery phases of their disorder. Social and vocational disability occurs in league with symptoms in greater or lesser proportions in each of the phases, again reminding us that there is no logical separation of treatment from rehabilitation.

Pharmacotherapy should be judiciously keyed to the type and severity of psychopathology at dosages that do not interfere with positive engagement in treatment or ability to learn skills during rehabilitation services. Thus, to prevent side effects such as sedation, weight gain, and neurologic problems from being obstacles to learning the skills necessary for community adaptation—as well as to ensure that dosages of psychotropic medications are adequate to maintain stability of symptoms—frequent intercommunication is necessary between the prescribing psychiatrist and the allied mental health workers who customarily are responsible for teaching social and independent living skills and reducing stress, tension, and the emotional temperature within the client's family or other home.

The psychiatrist gains vital information from the rehabilitation clinicians about the client's functional activity, which is of inestimable value in making decisions about selection and dosage of medications. Similarly, the rehabilitation staff can learn about the side effects that can be expected with new drug types and dosages. Also, by using information gained from the treating psychiatrist about shifting levels of symptoms, those who provide psychosocial treatments may change the social and instrumental role expectations of clients to prevent undue stress.

Ms. S was in a partial hospital program and had only nonintrusive, residual symptoms of her bipolar disorder. She exhibited tremor and lack of coordination that were side effects of her mood stabilizer and that made it difficult for her to participate in the program's psychoeducational groups. When her doctor was briefed about these problems, he switched Ms. S's mood stabilizer to one that was not associated with those neurologic side effects.

To be effective, skills training should be conducted with informed pharmacotherapy. Thus increases in medication dosage may be considered to keep the client stable when stress-related learning and skills training focus on particularly difficult personal goals.

When Mr. D was learning basic conversation skills, his progress was smooth and was not impeded by side effects of the low dosage of the antipsychotic medication he was taking. However, when he began supported employment paired with participation in the workplace fundamentals module (12), he encountered higher levels of stress, which the rehabilitation team communicated to the prescribing physician. A time-limited upward titration of Mr. D's medication dosage enabled him to be active in his job search and later to utilize problem-solving skills on the job, and he was successful in both attaining and sustaining employment.

A range of supportive social services—including housing, transitional and supported employment and education services, financial entitlements, and case management—can sustain a mentally disabled person in the community. Supports provide compensatory, external assistance in community reintegration, even after the very best evidence-based pharmacologic, psychoeducational, and skills training services have had only a partial impact.

Ms. M had recovered from the incapacitating symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder with the aid of an intensive cognitive-behavioral therapy program featuring exposure and response prevention plus clomipramine. However, when she was in stressful situations, such as attending community college or interacting with her young children at home, she found herself slipping back into her checking and staring rituals. She complained of difficulties studying, taking notes in class, and properly caring for her children and her husband. The treatment team arranged for a case manager, who was trained in skill building and exposure principles, to meet with Ms. M discreetly at her college and one hour a week in her home. It was suggested that Ms. M bring a laptop computer to her class, and she was taught to concentrate on taking notes in outline form that were as close to the teacher's lecture as possible. At home, Ms. M posted signs in her kitchen and on each door and mirror to remind herself to limit her checking and staring. With these supportive interventions, she successfully completed her community college course in accounting and became more focused and effective in carrying out her domestic responsibilities.

The importance of assessment in treatment and rehabilitation

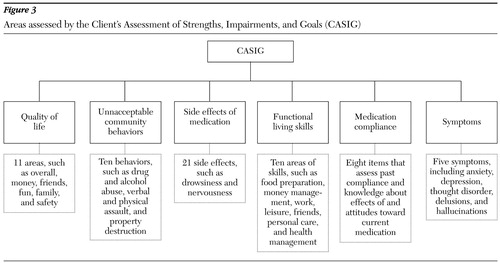

The assessment process is the road map for the journey from acute exacerbations to recovery. A thorough, structured assessment pinpoints the areas for rehabilitation and provides a baseline for monitoring its effects. Moreover, assessment within the framework of psychiatric rehabilitation, with its emphasis on positive goals and functioning linked to the current phase of illness and symptoms, fosters a collaborative relationship between the patient and the practitioner that greatly enhances the treatment process. One example of an interview-based, structured assessment is the Client's Assessment of Strengths, Interests, and Goals (13), which is depicted in Figure 3.

To guard against deviation from the rehabilitation pathway, the assessment process emphasizes the importance of focusing on the rehabilitation goals endorsed by the individual. However, empowering the client as a full and equal partner in treatment and rehabilitation may not always be easy. Negative symptoms, disabilities, intrusive hallucinations, institutionalization, and cognitive dysfunction may impede the client's ability to participate constructively in this crucial endeavor. The setting and resetting of short- and long-term goals provide the markers by which the clinician and the client can judge whether they are traveling in the same desired direction.

The clinician and the client are guided by the continuous interaction of the client's overall rehabilitation goals with the current stage of the disorder. As the client's symptoms stabilize, the focus shifts to helping the client define his or her goals in terms of occupational, school, friendship, familial, and residential roles. Still another shift occurs during the late rehabilitation and recovery phase, when individuals begin to look for goals that transcend their status as clients qua clients. In this phase, the overall goals are for the client to integrate into more normative community activities and acquire wellness, destigmatization, and self-esteem—factors that enable clients not only to manage but also, sometimes, to overcome their illness.

Logistically, a person's preferences, desires, and motivations should be operationalized in behavioral terms and divided into long-term and short-term goals. Long-term goals are cast in monthly to yearly time frames and should correlate with overall rehabilitation goals, serving as vehicles for achieving progress toward functional life roles. Long-term goals should be comprehensive in facilitating progress in all relevant domains of life functioning, including social and interpersonal, familial, financial, recreational, medical or psychiatric, activities of daily living or independent living skills, vocational or educational, spiritual, and housing or residential. Short-term goals should be cast in daily, weekly, or monthly time frames and should complement long-term goals as stepping-stones or subgoals. Short-term goals also must be prioritized and endorsed by all parties participating in the rehabilitation. To facilitate accomplishment of his or her goals, an individual should prioritize the goals and, when possible, have the goals endorsed by family members, caregivers, and responsible clinicians.

Mr. K was a 26-year-old man who had recently received a diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia. When his psychotic symptoms were controlled with antipsychotic medications, he engaged in a rehabilitation planning effort with an occupational therapist who was a member of a treatment team at a community mental health center. When asked to identify his goals, Mr. K said that he wanted to learn a trade and obtain employment that could enable him to live independently.

Once this goal of becoming independent was identified, Mr. K's therapist helped him set as a long-term goal resumption of his studies at a local trade school. Mr. K then began to work with his therapist to target skills and deficits in the areas of time management, organization of scheduled activities, and self-assertion, all of which he saw as essential to achieving his goal of entering school. Before he became ill, Mr. K had been a well-organized person with good study habits, so those were seen as potential assets. His basic conversational skills were more than adequate, but he needed training in speaking up for himself in the classroom, with teachers, and with peers. After six months, having benefited from structured and systematic skills training to improve his self-advocacy, Mr. K entered a course in automotive mechanics at a vocational school.

Treatment and rehabilitation of persons with dual diagnoses

People who have co-occurring mental and substance use disorders often experience multiple health and social problems and require treatment that cuts across several systems of care, including substance abuse treatment, mental health care, primary care, and social welfare services. Many people with co-occurring disorders receive treatment for only one of their disorders. Even when a person receives treatment for both, it is most often from separate, uncoordinated systems.

Providing the appropriate types of services presents formidable challenges in public health care settings. Nevertheless, model programs that integrate the needs of persons with dual diagnoses have been developed. For example, the substance abuse management module aims to teach skills necessary for managing the cravings, high-risk situations, and stressors that contribute to substance abuse (14). Substance abuse counselors, who often serve as skills trainers for this population, are taught to go slowly, in accordance with the cognitive deficits, negative symptoms, vulnerability to confrontation, and greater need for support that are characteristic of many persons with major mental illnesses. Similarly, behavioral family management has been adapted to the needs of clients with dual diagnoses by incorporating techniques that have been found useful in the treatment of substance abuse, including motivational interviewing and contingency management (15).

Involving families in treatment and rehabilitation

To improve disease management, we designed an intervention that integrated family psychoeducation with pharmacotherapy and social skills training. Multiple family groups, an evidence-based application of family psychoeducation with a 20-year record of proven effectiveness (16), was selected because of its emphasis on problem-solving skills and its flexibility, which enables practitioners to incorporate specific content addressing the issues germane to the treatment population.

The specific content chosen was the illness management program developed by Liberman and colleagues (17), which has been shown to improve the knowledge of clients with schizophrenia about the symptoms of their illness and the importance of medications in treating the illness. In a randomized controlled evaluation of the acquisition and generalization effects of this program, clients who participated in the program with their families exhibited significant increases in the use of illness management skills in their natural environments and experienced fewer rehospitalizations (18). The results highlighted the value of incorporating a generalization strategy based on family participation in the skills training enterprise to facilitate the use of skills in everyday living situations.

Treatment and rehabilitation of disabilities through employment

On the basis of their interests, skills, experience, and deficits, clients in supported employment are placed in regular jobs in community settings and then offered the training and supports necessary to maintain their positions. In the fully applied form of this approach, clients are offered services indefinitely, with job coaches visiting them in the workplace to help them learn and retain the technical, interpersonal, and problem-solving skills they need to sustain employment. However successful these supported employment programs are at placing clients in the competitive job market, job retention remains very difficult—50 percent of clients lose their job within six months (19).

The individual placement and support program is a model of supported employment for persons who have long-term impairments due to severe mental illness (20). The essence of this model is the integration of employment specialists into clinical case management and multidisciplinary mental health teams to provide clients with the full spectrum of treatments for maintaining competitive employment. A critical component of this model is that it is time unlimited. Follow-along supports and other clinical services—for example, modification of drug therapy as needed—from the integrated mental health team are necessary to sustain employment.

Controlled evaluations of the individual placement and support model of supported employment have revealed successful job placements in competitive, community-based work for approximately 50 percent of persons with serious mental illness who express a clear desire for employment. These outcomes are more than twice as great as those achieved through transitional employment or standard programs offered by state departments of vocational rehabilitation.

To minimize stress-induced relapses that can defeat the best-intentioned vocational rehabilitation efforts, practitioners and service systems must ensure that occupational goals are realistically linked to patients' assets and deficits, that progress is promoted incrementally with abundant supports and reinforcement, that pharmacotherapy and crisis intervention services remain accessible, and that social skills training is made available to help the worker develop social support inside and outside the workplace. In terms of the latter, a skills training program—the workplace fundamentals module—has been created and added to individual placement and support services to teach workers how to keep their jobs. A controlled study of this combined approach has demonstrated improved job retention rates over a two-year period compared with individual placement and support alone (21).

Integrating psychosocial and pharmacologic therapies

There is increasing evidence that optimal psychiatric treatment and rehabilitation, when offered in a coordinated, comprehensive, and continuous fashion, can facilitate symptomatic and social recovery from schizophrenia and other disabling mental disorders for a much greater proportion of individuals than are currently helped (22). However, what is needed is for clinicians to teach clients the skills they require to act as equal partners in treatment planning and implementation. The following case vignette illustrates the mobilization of clients to participate actively and knowledgeably in a combined medication and psychosocial approach.

Mr. B is a 23-year-old man with a five-year history of schizophrenia and who has had more than a dozen hospitalizations since the onset of his illness. He had resisted taking medication because of the side effects he had experienced, including severe akathisia, tremors, and muscle stiffness. He acknowledged that these medications had diminished his psychotic symptoms and improved his attention and concentration, but he resisted efforts to become more compliant with prescribed regimens. He also related that some of his psychotic symptoms, particularly auditory hallucinations, persisted at a low level despite changes in dosages and types of medications.

At that point, staff engaged Mr. B in a goal-setting process through which he identified his personal goals of living on his own without being hospitalized, taking little or no medication, and eventually getting a job. Mr. B's psychiatrist and social worker accepted these goals as laudable and set out to establish clear and measurable landmarks to gauge his success in pursuing them. With that accomplished, the psychiatrist and the social worker worked with Mr. B to identify the personal resources he possessed and the obstacles he faced in attaining his goals. Mr. B said that the most frustrating problem was his lack of understanding about his illness and its treatment, because this led to frequent relapses and concomitant life disruption.

Mr. B's psychiatrist and social worker next enrolled him in a structured educational program designed to increase his understanding of his illness, the medications used to treat the illness, and communication skills needed for negotiating his medication regimen with his psychiatrist. Mr. B also learned to develop a relapse prevention plan and methods for coping with persistent symptoms. He gained a good working knowledge of the ways he could minimize the medication side effects he found so intolerable, and he used new communication skills to contribute to decisions about the type and dosage of his medication. After agreeing to a trial of second-generation, Mr. B noticed less discomfort from extrapyramidal side effects. He used coping methods such as humming and reducing social stimulation to manage the persisting, low-level auditory hallucinations he experienced. This approach gave him a sense of mastery over his illness, and he adhered to his medication regimen. During the next year, he experienced two minor relapses but sought help from clinicians early in the prodromes of these relapses and did not require rehospitalization.

The key features of this example were that Mr. B's goals and personal desires were solicited, respected, and incorporated into the treatment plan; his resistance to medication was acknowledged in a straightforward, nonjudgmental, problem-solving manner; and he was taught skills he needed to become an effective collaborator in his own treatment and rehabilitation.

Conclusions

A comprehensive, coordinated, compassionate, and consumer-oriented integration of treatment with rehabilitation requires organizational mandates and supports. Unless the top managers and program administrators of services—within a given catchment area or systemwide—lend credence to the complexities of and requirements for high-fidelity use of an integrated approach and allocate the necessary resources, clinicians will not go the extra yard to adopt evidence-based innovations (23).

Support for integrated treatment and rehabilitation at the management and organizational levels is partly dependent, in turn, on adequate funding by policy makers—for example, legislators, county supervisors, governors, and the federal government. The current political zeitgeist is to limit improvements in mental health services to budget-neutral solutions, an unreasonable and perilous position according to Paul Appelbaum, immediate past-president of the American Psychiatric Association. Appelbaum highlighted the contradiction between enhancing mental health services for persons with serious mental illness and "cuts in Medicare reimbursements, the surrender of the Medicaid program to profit-making managed care companies, and reductions in state-funded, mental health programs" (24).

Even when clinicians are motivated by administrative support to alter their approaches in line with evidence-based practices, they face considerable regulatory, organizational, and professional barriers. Although it is possible to change treatment and rehabilitation modalities without additional funds, practitioners do need training and continuing consultation by experts or "knowledge transfer brokers" to learn new approaches and gain competence and confidence in the everyday use of these approaches. The dissemination of innovations in treatment and rehabilitation cannot be expected to occur through the conventional means of journal articles, books, and treatment manuals. The printed word must be supplemented by active, interpersonal contacts between clinicians and innovators who are both effective trainers and savvy organizational consultants.

To facilitate optimal improvement, comprehensive treatment programs for persons with serious mental disorders should integrate evidence-based pharmacologic, psychosocial, and learning-based interventions. The following principles, distilled from the results of many studies and practice guidelines, summarize current clinical wisdom about the integration of pharmacologic and psychosocial interventions (25).

First, pharmacologic treatment almost exclusively improves symptoms and reduces the risk of relapse. The ability of antipsychotic and other customary psychotropic drugs to improve neurocognition is still controversial, because any effects may be due to the presence or absence of concomitant anticholinergic drugs. Cholinergic drugs—for example, donepezil—appear to slow down the rate of dementia-related memory loss.

Second, the only way that pharmacologic treatment of major mental disorders leads to improvements in psychosocial functioning is when the individual has acquired the relevant psychosocial skills before developing the mental disorder and the removal or reduction of symptoms unmasks the person's preexisting functional abilities. Medications can never teach a person new functional skills; rather, they may remove the obstacles to the person's learning those skills through psychotherapeutic or educational procedures.

Third, psychosocial treatments affect primarily psychosocial functioning—social, vocational, educational, family, recreational, and self-care skills. Such improvements are likely to occur only when the psychosocial treatment directly targets the particular area of skill or functioning and is capable of providing training or compensatory support for that area of functional participation. Psychosocial treatments may reduce symptoms or risk of relapse to the extent that they are effective in ameliorating stressors that may induce exacerbations, promoting adherence to drug treatments and enhancing the individual's resilience and coping skills.

Fourth, both pharmacologic and psychosocial treatment have dosage-related therapeutic effects and side effects. Although it is well known that antipsychotic and antidepressant drugs may take days to weeks to have a therapeutic impact, it is less well known that psychosocial treatments have dose-response relationships as well. If the psychosocial treatment—for example, skills training—is well structured and incremental in its design and if it is provided for a sufficient number of sessions and for an appropriate duration, it may be significantly effective. On the other hand, if the psychosocial treatment is unstructured and overstimulating, aversive arousal and exacerbation of symptoms may ensue. Just as medications can exert prophylactic effects only for as long as they are administered, psychosocial treatments must also be delivered for lengthy periods and be offered as "booster" sessions to maintain their therapeutic and rehabilitative benefits.

Fifth, psychosocial treatment is most helpful for clients who are symptomatically stable or in reasonably good states of partial or full remission from florid symptoms, when they are able to absorb rehabilitation and need assistance in surmounting the problems and stresses of readjusting to the community. Stable levels of medication also favor positive responses to psychosocial treatments. Psychosocial treatment during acute flare-ups of symptoms should be aimed at calming the client, reducing levels of social and physical stimulation, and helping the client to integrate and understand the symptoms as part of an illness process.

Sixth, the most effective psychosocial treatment—whether provided by individual therapy, group or family therapy, day hospital, or inpatient milieu therapy—contains elements of practicality, concrete problem solving for everyday challenges, incremental shaping of social and independent living skills, and specific and attainable goals.

Finally, a continuing positive and collaborative relationship infused with hope, optimism, and mutual respect is central for treating clients with major mental disorders with pharmacologic or psychosocial treatments.

Dr. Kopelowicz is associate professor in the department of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) School of Medicine and medical director of the San Fernando Mental Health Center in Granada Hills, California. Dr. Liberman is professor in the department of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the UCLA School of Medicine and director of the UCLA Psychiatric Rehabilitation Program. Send correspondence to Dr. Kopelowicz at San Fernando Mental Health Center, 10605 Balboa Boulevard, Granada Hills, California 91344 (e-mail, [email protected]). This paper is part of a special section on integrated care for persons with mental illness.

Figure 1. The spectrum of interventions for mental disorders

Figure 2. The holistic integration of treatment and rehabilitation

Figure 3. Areas assessed by the Client's Assessment of Strengths, Impairments, and Goals (CASIG)

1. Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, et al: The functioning and well being of depressed patients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA 262:914–919, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Mintz J, Mintz LI, Arruda MJ, et al: Treatments of depression and the functional capacity to work. Archives of General Psychiatry 49:761–768, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Keller MB: Long-term treatment strategies in affective disorders. Pharmacological Bulletin 36(suppl 2):36–48, 200Google Scholar

4. West J, Duffy F, Marcus S, et al: Treatment of major depressive disorder in routine psychiatric practice. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, Philadelphia, May 18–23, 2002Google Scholar

5. Coryell W, Andreasen NC, Endicott J, et al: The significance of past mania or hypomania in the course and outcome of major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry 144:309–315, 1987Link, Google Scholar

6. Dion A, Tohen M, Anthony WA, et al: Symptoms and functioning of patients with bipolar disorder six months after hospitalization. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:652–657, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Miklowitz DJ, Goldstein MJ: Bipolar Disorder: A Family-Focused Treatment Approach. New York, Guilford, 1997Google Scholar

8. Bystritsky A, Liberman RP, Hwang S, et al: Social functioning and quality of life comparisons between obsessive-compulsive and schizophrenic disorders. Depression and Anxiety 14:214–218, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia. Washington, DC, APA, 1997Google Scholar

10. Smith TE, Hull JW, MacKain SJ, et al: Training hospitalized patients with schizophrenia in community reintegration skills. Psychiatric Services 47:1099–1103, 1996Link, Google Scholar

11. Kopelowicz A, Wallace CJ, Zarate R: Teaching psychiatric inpatients to re-enter the community: a brief method of improving continuity of care. Psychiatric Services 49:1313–1316, 1998Link, Google Scholar

12. Wallace CJ, Tauber R, Wilde J: Teaching fundamental workplace skills to persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 50:1147–1149, 1999Link, Google Scholar

13. Wallace CJ, Lecomte T, Wilde J, et al: CASIG: a consumer-centered assessment for planning individualized treatment and evaluating program outcomes. Schizophrenia Research 50:105–119, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Roberts LJ, Shaner A, Eckman TA: Overcoming Addictions: Skills Training for People With Schizophrenia. New York, Norton, 1999Google Scholar

15. Mueser KT, Glynn SM: Behavioral Family Therapy for Psychiatric Disorders. Oakland, Calif, New Harbinger, 1999Google Scholar

16. McFarlane WR: Multifamily Groups in the Treatment of Severe Psychiatric Disorders. New York, Guilford, 2002Google Scholar

17. Liberman RP, Wallace CJ, Blackwell G, et al: Innovations in skills training for the seriously mentally ill: the UCLA Social and Independent Living Skills Modules. Innovations and Research 2:43–60, 1993Google Scholar

18. Kopelowicz A, Zarate R, Smith V, et al: Disease management in Latinos with schizophrenia: a family-assisted, skills training approach. Schizophrenia Bulletin, in pressGoogle Scholar

19. Becker DR, Drake RE, Bond GR, et al: Job terminations among persons with severe mental illness participating in supported employment. Community Mental Health Journal 34:71–82, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Drake RE, Becker DR: The individual placement and support model of supported employment. Psychiatric Services 47:473–475, 1996Link, Google Scholar

21. Wallace CJ, Tauber R, Liberman RP: Combining the workplace fundamentals module with supported employment, manuscript in preparationGoogle Scholar

22. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A: Recovery from schizophrenia: a challenge for the 21st century. International Review of Psychiatry 14:245–255, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Goldman HH, Ganju V, Drake RE, et al: Policy implications for implementing evidence-based practices. Psychiatric Services 52:1591–1597, 2001Link, Google Scholar

24. Mulligan K: Mental Health Commission avoids crucial funding issues, Appelbaum says. Psychiatric News, December 6, 2002, p 62Google Scholar

25. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A, Smith TE: Psychiatric rehabilitation, in Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 7th ed. Edited by Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. New York, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999Google Scholar