Race, Gender, and Psychiatrists' Diagnosis and Treatment of Major Depression Among Elderly Patients

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined psychiatrists' contributions to racial and gender disparities in diagnosis and treatment among elderly persons. METHODS: Psychiatrists who volunteered to participate in the study were randomly assigned to one of four video vignettes depicting an elderly patient with late-life depression. The vignettes differed only in terms of the race of the actor portraying the patient (white or African American) and gender. The study participants were 329 psychiatrists who attended the 2002 annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. RESULTS: Eighty-one percent of the psychiatrists assigned the elderly patient a diagnosis of major depression. Patients' race and gender was not associated with significant differences in the diagnoses of major depression, assessment of most patient characteristics, or recommendations for managing the disorder. However, psychiatrists' characteristics, particularly the location of the medical school at which the psychiatrist was trained (United States versus international), were significantly associated with a number of variables. CONCLUSIONS: Given standardized symptom pictures, psychiatrists are no less likely to diagnose or treat depression among African-American elderly patients than among other patients, which suggests that bias based simply on race is not a likely explanation for racial differences in diagnosis and treatments found in earlier clinical studies. The impact of psychiatrists' having trained at international medical schools on diagnosis, treatment, and judgment of several patient attributes may indicate the need for targeted educational initiatives for aging and cultural competency.

Racial differences in rates of clinical diagnosis and treatment of depression have been well established both in mixed-age samples (1,2,3,4) and elderly samples (5,6,7,8,9). However, there is a paucity of studies that have attempted to examine why such differences are found. These differences may reflect a multitude of factors. Misdiagnosis and clinician bias are most frequently cited as possible etiologic factors (2,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17), although the evidence is limited (18) and is often indirect (16,17).

It is hazardous to infer bias solely from the existence of disparities in diagnosis and treatment (18). However, this inference has been made repeatedly, largely on the basis of the cross-classification of race and the diagnosis of psychotic and mood disorders (19). Furthermore, the word "bias" assumes that, given the same set of symptoms, clinicians will assign an African-American patient a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder and a white patient a diagnosis of an affective disorder. The issue of accurate diagnosis and treatment of depression is even more critical among elderly patients, for whom depression management is more complex because of the co-occurrence of medical illnesses and neuropsychiatric disorders. The potential mismanagement of a mood disorder that has been misdiagnosed as a psychotic disorder in an elderly patient from a racial minority group could lead to poor outcomes and side effects, such as tardive dyskinesia.

The Surgeon General's report on disparities in mental health care (20) notes that the role of clinician bias in racial differences in diagnosis remains a complex issue that demands an innovative series of studies. As a first step, we conducted the study reported here as a controlled experiment standardizing patient presentations to examine psychiatrists' diagnosis and treatment of older patients presenting with major depression. We hypothesized that patients' race (as indicated to the psychiatrists who participated in the study by skin color, facial features, and speech style) and gender would influence psychiatrists' diagnoses and management recommendations.

Methods

Survey instrument

Similarly to Schulman and colleagues (21), who examined race and gender effects on treatment recommendations in cardiology, we developed a computerized survey instrument that incorporated videotaped interviews and text to present depictions of late-life depression. In the videotaped interview, an actor played the role of an older patient with symptoms of depression. As in the study by Schulman and colleagues (21), we chose actors rather than patients for the vignettes because actors have the ability to read a script verbatim and to express consistent affect across vignettes. All interviews were recorded at a single studio (Russell Video Services, Ann Arbor, Michigan), and the actors followed identical scripts and direction, dressed in similar clothing, and displayed the same affect within video segments. The video recordings were produced by ImageWeaver Studios, a company with expertise in the production of educational medical videos.

The four five-minute videos consisted of scripted interviews with the patient-actors. The script for major depression was written and reviewed by four board-certified geriatric psychiatrists. Established DSM-IV criteria for major depression were met. The script was also designed to capture the frequent medical and neuropsychiatric complexity of late-life depression (22) and to introduce ambiguity such that the diagnosis would not be entirely obvious. Thus, in addition to the symptoms of depression that were presented, symptoms were included that suggested possible psychosis, cognitive problems, and alcohol use. The written vignette was then pilot tested individually with two board-certified psychiatrists who had been blinded to the purpose of the study. Both psychiatrists assigned the patient a diagnosis of major depression.

The four actors who were recruited to portray the patients in the videos (Figure 1) represented the four combinations of race and gender: white female, white male, African-American female, and African-American male. The four video vignettes were then each piloted separately with at least two additional board-certified psychiatrists (12 psychiatrists in total). These psychiatrists were also blinded to the purpose of the study; their rate of agreement on diagnosis was 93 percent.

The videotaped interviews were introduced by a computer screen that listed the patient's age (73 years), medical conditions (diabetes, arthritis, and hypertension), insurance (Medicare and Blue Cross-Blue Shield supplemental insurance), and the information that the patient was "brought in" by his or her daughter. A survey instrument asked psychiatrists to choose the single best DSM-IV diagnosis for the patient on the basis of information included in the video. They were then asked for their degree of certainty in making this primary diagnosis. The psychiatrists were then presented with possible treatment choices and were asked to select their initial treatment on the basis of the information presented. The final portion of the instrument assessed psychiatrists' judgment about patient characteristics, modified from a survey by Schulman and colleagues (personal communication, Schulman KA, 2002. These patient characteristics included personal attributes and predicted behaviors. The software program required that all components of the 15-minute survey (including the entire vignette) be presented to each psychiatrist before the survey questions were answered.

Study participants and data collection

The psychiatrists who participated in this study were attendees at the 2002 annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, held in Philadelphia. U.S.-practicing and postresidency psychiatrists who registered for the meeting in advance were mailed a postcard inviting them to participate in the study with the incentive of a food gift; participants were also recruited on-site. Potential participants were told that they were taking part in a "clinical decision-making" study but were not told that the study's primary purpose was to assess the effects of patients' race and gender.

The psychiatrists were randomly assigned to view one of the four vignettes. The survey instrument was administered in a booth in the main exhibit hall that had six individual computer stations. The layout of the stations was designed to provide privacy to the participants and to prevent them from viewing each other's video interviews and surveys. The booth was independent of pharmaceutical company booths and other booths or materials that may have been suggestive of a diagnosis of depression.

Statistical analysis

Factors associated with psychiatrists' assessments of patient characteristics on the basis of the four randomly assigned video vignettes were examined by using the following analyses. First, univariate (mean and standard deviation) and bivariate (Spearman and Pearson correlations) descriptive statistics were calculated overall and by vignette. One-way analysis of variance was used to examine differences between the vignette groups in continuous outcome measures. The Tukey-Kramer method was used in relevant post hoc multiple comparison tests, with significance levels adjusted by the number of tests. Chi square tests were used to examine patterns of association and independence among categorical variables. Post hoc analyses were conducted on physician characteristics. Separate logistic regression models were computed for each physician characteristic, with patients' race and gender included as predictor variables. All tests were two-tailed, and a criterion significance level of .05 was used throughout, except where adjusted for multiple comparisons. All analyses were performed with SAS statistical software.

Results

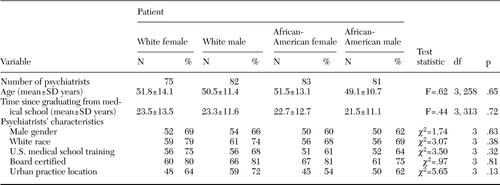

A total of 329 psychiatrists volunteered to participate in the study. Eight psychiatrists dropped out before viewing their assigned vignette. The remaining psychiatrists (N=321) who were randomly assigned to each vignette group did not differ significantly on any characteristic examined (Table 1).

Primary diagnosis

A total of 260 psychiatrists (81 percent) assigned a diagnosis of major depression to the patient in the vignette. Analysis of the sample by vignette group showed no significant differences in the percentages of psychiatrists who diagnosed major depression: 73 percent (55 psychiatrists) for the white female vignette, 83 percent (68 psychiatrists) for the white male vignette, 80 percent (66 psychiatrists) for the African-American female vignette, and 88 percent (71 psychiatrists) for the African-American male vignette. Assigned diagnoses other than depression included dementia, alcohol abuse, delusional disorder, and schizoaffective disorder.

Level of certainty in diagnosis

Among the psychiatrists who assigned a diagnosis of major depression, there were no significant differences in mean level of certainty in the diagnosis (rated as zero to 100 percent) by vignette: 65±17.68 percent for the white female vignette, 65±19.94 percent for the white male vignette, 66±20.08 percent for the African-American female vignette, and 64±19.03 percent for the African-American male vignette.

Management recommendations

A majority of the psychiatrists chose an antidepressant as their first-line treatment; this choice was consistent across vignettes: 77 percent (58 psychiatrists) for the white female vignette, 78 percent (64 psychiatrists) for the white male vignette, 75 percent (62 psychiatrists) for the African-American female vignette, and 77 percent (62 psychiatrists) for the African-American male vignette. A majority of the psychiatrists chose newer antidepressant agents, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, as their first-line treatment, and this choice did not differ significantly by vignette: 73 percent (55 psychiatrists) for the white female vignette, 76 percent (62 psychiatrists) for the white male vignette, 75 percent (62 psychiatrists) for the African-American female vignette, and 77 percent (62 psychiatrists) for the African-American male vignette. For the sample overall, psychiatrists who assigned a diagnosis of major depression were significantly more likely to choose a newer antidepressant (229 psychiatrists, or 88 percent) compared with those who assigned other diagnoses (12 psychiatrists, or 20 percent) (χ2=123.56, df=1, p<.001).

A majority of the psychiatrists recommended long-term follow-up (more than six months), and this did not differ significantly by vignette: 67 percent (50 psychiatrists) for the white female vignette, 79 percent (65 psychiatrists) for the white male vignette, 67 percent (55 psychiatrists) for the African-American female vignette, and 73 percent (59 psychiatrists) for the African-American male vignette. Psychiatrists also consistently indicated that the single piece of additional information desired was a full medical history with laboratory work: 49 percent (37 psychiatrists) for the white female vignette, 51 percent (42 psychiatrists) for the white male vignette, 57 percent (47 psychiatrists) for the African-American female vignette, and 53 percent (43 psychiatrists) for the African-American male vignette. Other additional information chosen by participants included head CT, full substance abuse history, and Mini-Mental State Examination.

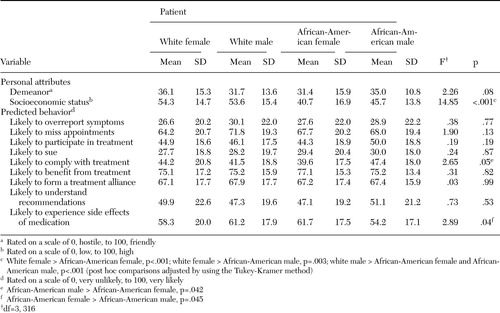

Psychiatrists' assessment of patient characteristics

The psychiatrists were asked to assess two personal attributes of the patient—demeanor and socioeconomic status—as well as nine predicted patient behaviors. The psychiatrists' assessments did not differ significantly by patients' race or gender (Table 2), with the exceptions of the psychiatrists' estimates of the patient's socioeconomic status, adherence to treatment, and likelihood of experiencing side effects of medication. Post hoc comparisons indicated that the patients portrayed in both the white male and the white female vignettes were rated as being of significantly higher socioeconomic status than those portrayed in the African-American male and African-American female vignettes (Tukey-Kramer test, p<.05). The African-American female patient was rated as less likely to adhere to treatment (Tukey-Kramer test, p<.05) and more likely to experience side effects of medication (Tukey-Kramer test, p<.05) than the African-American male patient.

Psychiatrists' estimates of socioeconomic status were not associated with their choice of diagnosis or estimate of patient attributes, except for demeanor. A significant relationship was found between rating of socioeconomic status and estimates of patient demeanor (lower socioeconomic status associated with a more hostile demeanor) (F=5.09, df=1, 312, p<.03); estimate of patient demeanor also appeared to account for some of the variation in the estimate of socioeconomic status among the vignettes (F=3.05, df=3, 312, p<.03).

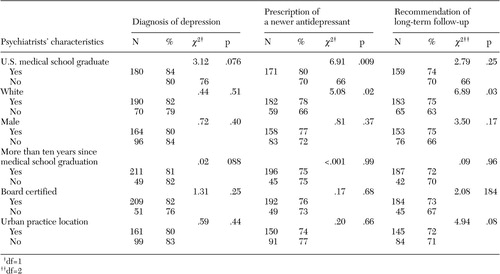

Analyses using psychiatrist characteristics

Diagnosis, treatment, and management recommendations for all patients, by psychiatrist characteristics, are presented in Table 3. Notably, the location of the medical school at which the psychiatrists received their training (United States versus an international medical school) and psychiatrists' race were each associated with psychiatrists' diagnosis and management recommendations. Overall, 67 percent of the total sample (215 psychiatrists) were graduates of U.S. medical schools, and 33 percent (106 psychiatrists) were graduates of international medical schools. The overall racial breakdown of the psychiatrists was 72 percent white (232 psychiatrists), 19 percent Asian (60 psychiatrists), 5 percent other (15 psychiatrists), 2 percent African American (seven psychiatrists), and 2 percent Hispanic (seven psychiatrists). For graduates of international medical schools, the racial breakdown was 49 percent Asian (52 psychiatrists), 35 percent white (37 psychiatrists), 8 percent other (eight psychiatrists), 5 percent Hispanic (five psychiatrists), and 4 percent African American (four psychiatrists).

Graduates of international medical schools were less likely to diagnose depression and significantly less likely to choose a newer antidepressant as a first-line treatment than graduates of U.S. medical schools. Compared with white psychiatrists, psychiatrists of other races were significantly less likely to choose a newer antidepressant as a first-line treatment and to recommend long-term follow-up. Psychiatrists' gender, board certification status, time since graduation, and practice location were not associated with diagnosis or with management recommendations.

In terms of assessment of patients' characteristics, graduates of international medical schools were significantly more likely than U.S. graduates to indicate that the patients portrayed in three of the four vignettes were overreporting symptoms (white male, t=-2.64, df=80, p<.01; African-American female, t=-3.62, df=80, p<.001; and African-American male, t=-3.12, df=79, p<.003). Significantly more international graduates rated the African-American female as being more likely to sue for malpractice (t=-2.04, df=80, p<.05) and the African-American male as being less likely to understand the psychiatrist's recommendations (t=2.00, df=79, p<.05). Finally, compared with graduates of international medical schools, U.S. medical school graduates were more likely to predict that the white female patient would experience side effects of medication (t=2.26, df=73, p<.03).

Compared with white psychiatrists, psychiatrists of other races were more inclined to indicate that the white male patient was overreporting symptoms (t=-3.07, df=80, p<.004) and was more likely to sue for malpractice (t=-2.67, df=80, p<.01). Psychiatrists of other races also rated the African-American female patient as being of lower socioeconomic status (t=2.41, df=80, p<.02).

Post hoc analyses of psychiatrists' characteristics

Separate logistic regression models were computed for each psychiatrist trait, with patients' race and gender included as predictor variables. The results for diagnosis indicated that the effect of patients' gender was significant across all models, except for number of years in practice—male patients were 1.8 times as likely to receive a diagnosis of depression as female patients (95 percent confidence interval [CI]=1.03 to 3.26). The interaction between patients' gender and race was examined and was found to be nonsignificant.

Psychiatrists' race as well as the location of the medical school at which they were trained were significantly associated with choice of newer antidepressants (p<.05). Psychiatrists' race and medical school location were highly correlated (Spearman rank-order correlation coefficient [rs]=.59, p<.001); 84 percent of the white psychiatrists (196 of 232) had been trained in the United States, whereas only 22 percent of the other psychiatrists (20 of 89) had been trained in the United States (χ2=112, df=1, p<.001). Neither patients' race nor patients' gender was predictive of treatment choice in any of the models.

Discussion and conclusions

Although clinician bias is often cited as a possible explanation for racial disparities in the diagnosis of depression, psychiatrists' contribution to the disparities had not been directly examined before our study. Misdiagnosis among older African-American patients was suggested by two case series (16,17). However, it is not clear from these case series whether the misdiagnosis was racially based or was due to nonracially based misdiagnosis that may have been more prevalent before the DSM-III era. Our findings suggest that psychiatrist bias based simply on the color of a patient's skin (as well as other characteristics associated with race, such as facial features and speech style) does not explain the lower rates of diagnosis of clinical depression among African-American patients.

In clinical settings, the diagnosis and treatment of depression may be affected by other patient-level factors, including variations in presentation of symptoms of depression, lower use of formal mental health care settings for treatment among elderly African Americans, and patients' treatment preferences. The first factor is suggested by previous findings that mixed-age African-American patients with depression had higher ratings of hostility and irritability and a greater frequency of somatic complaints (1,23,24). The second factor may be indicated by studies demonstrating different patterns of help seeking and service use for depression among African Americans, including lower use of mental health specialists (25) and more reliance on informal support (for example, friends or ministers) for emotional problems (26,27). Furthermore, elderly patients, men, and African Americans are more likely to see primary care physicians than psychiatrists for mental health treatment (28). It is possible that there are greater disparities in mental health care among primary care patients than among patients who are seen by psychiatrists.

The third factor is supported by a recent finding that primary care providers recognized depression and recommended treatment for African-American patients as often as for white patients, but African-American patients were significantly less likely to accept antidepressant medications (29). Previous studies that showed lower rates of diagnosis and treatment of clinical depression among elderly African Americans may have been affected by variations in symptom presentations, selection bias in examining samples of patients who presented for treatment, and the effects of patients' treatment preferences. A strength of our study was the fact that patients' presentations were standardized to enable us to isolate and examine psychiatrists' decision making. Given our results as well as those of these other studies, we suggest that racial disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders are likely the result of a complex interplay of patient and provider factors and cannot be merely ascribed to "misdiagnosis."

Regarding the findings on psychiatrists' estimates of patients' socioeconomic status and of race and diagnosis, it is possible that psychiatrists based their estimates of socioeconomic status on known population differences in income as opposed to racial bias. Alternatively, it is possible that, even if psychiatrists' estimates of socioeconomic status were influenced by racial bias, this bias did not affect the psychiatrists' choices of diagnosis.

Although patients' race and gender had a limited effect on psychiatrists' decision making and estimate of patients' characteristics, certain characteristics of the psychiatrists themselves—notably, whether they attended a U.S. medical school or an international medical school—did have an impact. Psychiatrists who graduated from international medical schools, most of whom were Asian, were less likely to diagnose depression or to recommend newer antidepressants as initial treatment and more likely to predict negative behaviors, such as nonadherence to medications, for both white and African-American patients. These findings may reflect cultural differences within the psychiatrist-patient dyad. Graduates of international medical schools frequently work in the public sector, where they encounter patients from racial minority groups and spend, on average, 35 percent more time working with elderly patients than do graduates of U.S. medical schools (30). Thus these results are of practical concern and may suggest the need for targeted educational initiatives for cultural and aging competency for psychiatrists who are graduates of international medical schools.

Our study had several limitations. First, we used videotaped vignettes of actors portraying patients. Although we meticulously standardized and piloted the vignettes, subtle differences between actors' appearances or nonverbal communication might have affected our results. The use of case vignettes to assess clinical decision making is supported by several studies (31,32,33,34); videotaped (rather than written) vignettes may enhance the accuracy of physicians' decisions (34). Such techniques also permit a degree of control that is unattainable in observational studies, allowing determination of the influence of nonmedical factors on physicians' decision making (35). However, it is not known whether our survey instrument correlates with actual psychiatrists' decision making.

It is also possible that the study participants' knowledge of the previous study by Schulman and colleagues (21) that had been the subject of wide discussion affected our results. However, we requested that study personnel note any mention of or questions about that study by the participants in our study; no participant mentioned this previous study. It is likely that, given the elapsed time between the publication of the Schulman study and the implementation of our study (three years), the different setting and focus of the meeting at which study participants were recruited (cardiology versus psychiatry), and the fact that each participant viewed only one vignette (and in many cases thought this was the only vignette), most participants did not make a connection between the Schulman study and our own.

In addition, the fact that we recruited psychiatrists at a national meeting may have resulted in a nonrepresentative sample. Psychiatrists who attend such meetings and who volunteer to participate in a study such as ours may be more attuned to the culturally sensitive diagnosis of depression. Finally, to enable us to focus on the relationship between patients' race and psychiatrists' decision making, other patient-related factors (such as socioeconomic status or educational level) were not assessed. However, clearly these factors may have an impact on physicians' decision making.

These limitations notwithstanding, the results of this study provide new data on the contribution of psychiatrists to racial differences in the diagnosis and treatment of late-life depression. It has been suggested that racial disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders are related to inferior treatment provided by white professionals (36) and that schizophrenia among black patients is systematically overdiagnosed whereas affective disorders are systematically underdiagnosed among black patients (37). However, until the elements of the treatment process (provider-related variables and patient-related variables) are broken down and examined, these assumptions about causality are merely conjecture.

Our findings suggest that, given standardized symptom pictures, psychiatrists are no less likely to diagnose depression among African-American elderly patients than among other patients and do not show evidence of bias based simply on race. Differences in rates of diagnosis and treatment of clinical depression that were found in previous studies may instead reflect the complex interplay between provider factors and patient-related factors, such as variations in the use of health care services, alternative presentations of symptoms, and patients' preferences. The impact of psychiatrists' having trained at international medical schools on diagnosis, treatment choice, and ratings of patients' attributes may suggest a need for targeted cultural and aging competency initiatives for such psychiatrists, many of whom provide important and much-needed care in the public sector to elderly patients from racial minority groups.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a Health Services Research and Development Research Career Development Award from the Department of Veterans Affairs, a Pfizer/American Geriatrics Society 2001 Postdoctoral Fellowship for Research on Health Outcomes in Geriatrics, an unrestricted grant from Pfizer, Inc., and the University of Michigan Rachel Upjohn Clinical Scholars Program.

Dr. Kales, Dr. Blow, Ms. Gillon, and Ms. Welsh are affiliated with the Serious Mental Illness Treatment Research Education and Clinical Center (SMITREC) of the Department of Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System. Dr. Kales, Dr. Blow, Dr. Taylor, Dr. Maixner, and Dr. Mellow are affiliated with the department of psychiatry of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Dr. Mellow is also with the VISN 11 Mental Health Service Line of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Neighbors is with the department of health behavior and health education at the University of Michigan School of Public Health. Send correspondence to Dr. Kales at Psychiatry Service 116A, VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, 2215 Fuller Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48105 (e-mail, [email protected]). This paper was presented in part at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry held March 1 to 4, 2003, in Honolulu.

Figure 1. Patients as portrayed by actors in a computerized survey of physicians' diagnoses

|

Table 1. Characteristics of psychiatrists who assessed one of four patient vignettes, according to the race and sex of the patient in the vignette

|

Table 2. Psychiatrists' assessments of characteristics of patients portrayed in four vignettes

|

Table 3. Relationship between psychiatrists' characteristics and diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up recommendations for patients portrayed in four vignettes

1. Adebimpe VR, Hedlund JL, Cho DW, et al: Symptomatology of depression in black and white patients. Journal of the National Medical Association 74:185–190,1982Medline, Google Scholar

2. Jones BE, Gray BA: Problems in diagnosing schizophrenia and affective disorders among blacks. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:61–65,1986Abstract, Google Scholar

3. Strakowski SM, Shelton RC, Kolbrener ML: The effects of race and comorbidity on clinical diagnosis in patients with psychosis. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 54:96–102,1993Medline, Google Scholar

4. Flaskerud JH, Hu L: Relationship of ethnicity to psychiatric diagnosis. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:296–303,1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Mulsant BH, Stergiou A, Keshavan MS, et al: Schizophrenia in late life: elderly patients admitted to an acute care psychiatric hospital. Schizophrenia Bulletin 19:709–721,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Fabrega H, Mulsant BH, Rifai AH, et al: Ethnicity and psychopathology in an aging hospital-based population. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 182:136–144,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Leo RJ, Narayan DA, Sherry C, et al: Geropsychiatric consultation for African American and Caucasian patients. General Hospital Psychiatry 19:216–222,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Kales HC, Blow FC, Bingham CR, et al: Race and inpatient psychiatric diagnoses among elderly veterans. Psychiatric Services 51:795–800,2000Link, Google Scholar

9. Blazer DG, Hybels CF, Simonsick EM, et al: Marked differences in antidepressant use by race in an elderly community sample:1986–1996. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1089–1094,2000Google Scholar

10. Bell CC, Mehta H: The misdiagnosis of black patients with manic-depressive illness. Journal of the National Medical Association 72:141–145,1980Medline, Google Scholar

11. Mukherjee S, Shukla S, Woodle J, et al: Misdiagnosis of schizophrenia in bipolar patients: a multi-ethnic comparison. American Journal of Psychiatry 140:1561–1574,1983Google Scholar

12. Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR (eds): Institute of Medicine: Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2002Google Scholar

13. Garb HN: Race bias, social class bias, and gender bias in clinical judgment. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 4:99–120,1997Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Abreu JM: Conscious and nonconscious African American stereotypes: impact on first impression and diagnostic ratings by therapists. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 67:387–393,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Van Ryn, Burke J: The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physician's perceptions of patients. Social Science and Medicine 50:813–828,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Coleman D, Baker FM: Misdiagnosis of schizophrenia among older black veterans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 182:527–528,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Baker FM: Misdiagnosis among older psychiatric patients. Journal of the National Medical Association 87:872–876,1995Medline, Google Scholar

18. Snowden LR: Bias in mental health assessment and intervention: theory and evidence. American Journal of Public Health 93:239–243,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Neighbors HW, Trierweiler SJ, Ford BC, et al: Racial differences in DSM diagnosis using a semi-structured instrument: the importance of clinical judgement in the diagnosis of African Americans. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 44:237–256,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 2001Google Scholar

21. Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W, et al: The effect of race and sex on physicians' recommendations for cardiac catheterization. New England Journal of Medicine 340:618–626,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Katz IR, Streim J, Parmalee P: Psychiatric-medical comorbidity: implications for health services delivery and for research on depression. Biological Psychiatry 36:141–145,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Baker FM: Mental health issues in elderly African-Americans. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine 11:1–13,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Husaini BA, Moore ST: Arthritis disability, depression, and life satisfaction among black elderly people. Health and Social Work 25:253–260,1990Google Scholar

25. Gallo JJ, Marino S, Ford D, et al: Filters on the pathway to mental health care: II. sociodemographic factors. Psychological Medicine 25:1149–1160,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Neighbors HW, Jackson JS: The use of informal and formal help: four patterns of illness behavior in the black community. American Journal of Community Psychology 12:629–644,1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Neighbors HW, Musick MA, Williams DR: The African American minister as a source of help for serious personal crises: bridge or barrier to mental health care? Health Education and Behavior 25:759–777,1998Google Scholar

28. Pingitore D, Snowden L, Sansone RA, et al: Persons with depressive symptoms and the treatments they receive: a comparison of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 31:41–60,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Miranda J, Cooper LA: Disparities in care for depression among primary care patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine19:120–126,2004Google Scholar

30. Blanco C, Carvalho C, Olfson M, et al: Practice patterns of international and US medical graduate psychiatrists. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:445–450,1999Abstract, Google Scholar

31. Wigton RJ, Poses RM, Collins M, et al: Teaching old dogs new tricks: using cognitive feedback to improve physician's diagnostic judgments on simulated cases. Academic Medicine 65:(suppl):S5-S6, 1990Google Scholar

32. Jones TV, Gerrity MS, Earp JA: Written case simulations: do they predict physicians' behavior? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 43:805–815,1990Google Scholar

33. Kirwan JR, Chaput de Saintonge DM, Joyce CRB, et al: Clinical judgment in rheumatoid arthritis: I. rheumatologists' opinion and the development of "paper patients." Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 42:644–647,1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. McNutt RA, O'Meara JJ, de Bliek R: The effect of visual information and order of patient presentation on the accuracy of physicians' estimates of acute ischemic heart disease: a pilot study. Medical Decision Making 12:342,1992Google Scholar

35. Feldman HA, McKinlay JB, Potter DA, et al: Nonmedical influences on medical decision making: an experimental technique using videotapes, factorial design, and survey sampling. Health Services Research 32:343–366,1997Medline, Google Scholar

36. Carter JH: Culture, race, and ethnicity in psychiatric practice. Psychiatric Annals 34:500–504,2004Crossref, Google Scholar

37. Adebimpe VR: A second opinion on the use of white norms in psychiatric diagnosis of black patients. Psychiatric Annals 34:543–551,2004Crossref, Google Scholar