Race and Inpatient Psychiatric Diagnoses Among Elderly Veterans

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Limited data exist on differential rates of psychiatric diagnoses between ethnocultural groups in the elderly population. The purpose of this study was to examine more closely the issue of race and rates of psychiatric diagnoses among elderly inpatients. METHODS: The national sample included 23,758 veterans age 60 or over admitted in 1994 to acute inpatient units in Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals. Psychiatric diagnosis determined inclusion in one of six diagnostic groups: cognitive, mood, psychotic, substance use, anxiety, and other disorders. The study also assessed rates of psychiatric diagnoses among patients admitted to psychiatric units only and by age group and treatment setting, such as the size of the hospital and whether it had an academic affiliation. RESULTS: Compared with elderly Hispanic and Caucasian patients, a significantly higher proportion of elderly African-American patients were diagnosed as having cognitive disorders and substance use disorders, and a significantly lower proportion were diagnosed as having mood and anxiety disorders. Hispanic and African-American patients had significantly higher rates of psychotic diagnoses than Caucasian patients. For all diagnoses except cognitive disorders, these differential rates were also found among patients admitted to psychiatric units only. Age and treatment setting appeared to moderate some of the differences in diagnostic rates, except for mood disorders. In every analysis performed, the rate of mood disorder diagnoses among elderly African-American patients was less than half the rate among elderly Caucasian patients. CONCLUSIONS: The findings suggest that elderly African-American veterans admitted to VA inpatient units have strikingly lower rates of mood disorder diagnoses. Future studies should examine the contribution of both patient and provider factors to these differences.

Among all age groups, differential rates of clinical psychiatric diagnoses, such as higher rates of psychotic disorder diagnoses and lower rates of mood disorder diagnoses, have been reported among African Americans and Caucasians (1,2,3,4,5). A multitude of factors have been cited for the differences, including differences in exposure to risk factors, in symptoms or presentations of psychiatric illness, and in concepts of illness as well as genetic factors, communication barriers, the ethnocentric bias of diagnosticians, misdiagnosis, and confounding factors such as lower socioeconomic status or education level (3,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14).

In two studies of psychiatric inpatients in which diagnoses were based on structured interviews or research diagnostic criteria, diagnostic rates among African Americans were similar to those among Caucasians (11,15). The Epidemiological Catchment Area study found a slightly lower rate of affective disorders among African Americans than among Caucasians (16), while the National Comorbidity Survey found a significantly lower prevalence of affective disorders among African Americans than among Caucasians (17).

In the elderly population, data on differential rates of various psychiatric diagnoses among racial groups are limited. Two separate studies have focused on elderly patients admitted to geropsychiatric acute inpatient units. Mulsant and associates (18) found that African-American inpatients were significantly more likely to receive a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and Fabrega and colleagues (19) noted a lower proportion of African Americans with mood disorders and a higher proportion with psychotic disorders. In addition, Zubenko and coworkers (20) reported that among patients with Alzheimer's disease, African Americans were more likely to receive a diagnosis of dementia with delusions. Finally, a study examining geropsychiatric consultation found that consultants diagnosed psychotic disorders and dementia significantly more often among elderly African-American persons than among elderly Caucasians and diagnosed mood disorders significantly less often (21).

Two studies have suggested that misdiagnosis may be at the root of the different rates of clinical psychiatric diagnoses in the elderly population. In a Veterans Affairs setting, Coleman and Baker (22) found that seven of eight middle-aged and elderly African-American patients with affective disorders had been misdiagnosed as having schizophrenia. Baker (23) found that four of ten African Americans referred to a community mental health care center with a diagnosis of schizophrenia actually had other psychiatric diagnoses.

The aforementioned studies have largely been focused on single settings—either single clinics or psychiatric units—where it is possible that factors unique to those settings were in operation. To our knowledge, no studies have looked for differences between races in rates of clinical psychiatric diagnoses among elderly inpatients in a health care system. Diagnostic rates are very important, because diagnosis often determines the type of care received. The VA serves a large, racially diverse clinical population of elderly veterans. African-American veterans may be more likely than Caucasian veterans to use VA mental health services (24) or VA inpatient mental health treatment (25). Thus an examination of diagnostic rates among inpatients in the VA system could have broad-based implications for the treatment of elderly African-American veterans.

The purpose of this study was to examine further the issue of differential rates of psychiatric diagnoses among races in a large cohort of older inpatients in the VA health care system. If differential rates of psychiatric diagnoses were seen between races, we felt that further examination of the effects of age and treatment setting on these differences would be worthwhile. Accuracy in diagnosing schizophrenia in VA medical centers has been found to be related to whether the center is affiliated with a medical school (26).

Methods

Data were obtained retrospectively from the VA patient treatment file. This national computerized database contains discharge records from all VA medical centers in the U.S. It includes information on patients' characteristics, such as age, race, sex, and marital status, as well as administrative data, such as admission and discharge dates and discharge diagnoses. The latter include the primary diagnosis responsible for hospitalization and secondary diagnoses.

Fiscal year 1994 (October 1, 1993, to September 30, 1994) was the index year for our study. We obtained data for that year from the patient treatment file and identified all patients at least 60 years old who were hospitalized for a primary ICD-9-CM (27) psychiatric diagnosis. We then identified patients of Caucasian, African-American, and Hispanic ethnicity to compare rates of diagnosis. Veterans from other racial groups were excluded because of extremely small numbers in this age group.

A total of 23,758 elderly patients were identified. Individuals were grouped into six categories according to the diagnosis responsible for the hospitalization. The categories were based on DSM-III-R groupings and included cognitive disorders, including dementia and delirium; mood disorders, including major depression and bipolar disorder; psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia, delusional disorders, and psychotic disorders not otherwise specified; substance use disorders; anxiety disorders, including posttraumatic stress disorder; and all other disorders, including personality disorders and somatization disorders. Persons who had a mood disorder with secondary psychosis were included in the mood disorders category.

Demographic variables included age, race, gender, and marital status. The treatment setting for the index admission and the discharge location were also examined. The former was determined using categories called resource allocation groups, which were developed for VA use; they divide VA hospitals into six groupings by size, academic affiliation, focus, and location (28).

Sociodemographic characteristics were compared using chi square tests of independence (3 × 2 design) for categorical differences and three-group one-way univariate analysis of variance for differences in continuous variables. Configural frequency analysis was used to test the main hypotheses of the study (29). Configural frequency analysis is designed to identify local associations among discrete variables. Two kinds of local associations are identified—types and antitypes. Types are associations in which the observed frequency is significantly greater than the expected frequency. Antitypes are associations that occur significantly less frequently than would be expected as a result of chance. Configural frequency analysis identifies configurations that are multivariate in nature and that are unique from the other local associations in terms of their likelihood of occurrence. In the study reported here, configural frequency analysis was used to identify statistically common and rare configurations occurring among diagnosis, race, age, and treatment setting.

Results

The sample of 23,758 veterans consisted of 861 Hispanic patients, 19,359 Caucasian patients, and 3,538 African-American patients.

Sociodemographic characteristics

The mean±SD age of the sample was 69.7±7.0 years. African Americans and Caucasians, who had mean±SD ages of 69.6±7.3 and 70±7 years, respectively, were significantly older than Hispanic patients, who had a mean age of 69±6.3 (F=6.58, df=2, 23,755, plt;.001). Among the Caucasian patients were 495 women (2.6 percent), a proportion significantly larger than among Hispanic or African-American patients (χ2=36.79, df=2, p<.001). Only 1 percent of Hispanic patients (nine patients) and 1 percent of African-American patients (37 patients) were women. Hispanic patients were more likely to be married than Caucasian or African-American patients (χ2=102.01, df=2, p< .001). A total of 466 Hispanic patients (54.1 percent) were married, compared with 8,092 Caucasian patients (41.8 percent) and 1,272 African-American patients (36 percent).

Hispanic patients were more likely than Caucasian or African-American patients to be discharged to the community after the index hospitalization (χ2=94.31, df=4, p<.001). A total of 720 Hispanic patients were discharged to the community (83.6 percent), compared with 13,759 Caucasians (71.1 percent) and 2,688 African Americans (76 percent). The latter two groups were much more likely to be discharged to a VA or community nursing home than were Hispanic patients. Seventy Hispanic patients (8.1 percent), 2,924 Caucasian patients (15.1 percent), and 457 African-American patients (12.9 percent) were discharged to a VA or community nursing home.

Racial differences in diagnoses

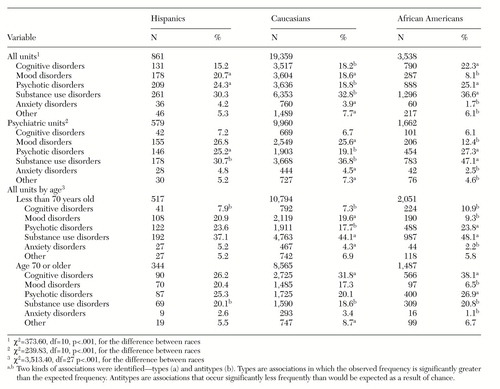

Table 1 presents the percentages of patients in each diagnostic category by race for all types of hospital units. A significantly larger percentage of elderly African-American patients were diagnosed as having cognitive disorders and substance use disorders, compared with elderly Hispanic or Caucasian patients. A significantly smaller proportion of the African-American patients had mood or anxiety disorders, compared with the Hispanic or Caucasian patients. Also, the proportion of African-American and Hispanic patients with psychotic disorders was significantly larger than the proportion of Caucasian patients with this diagnosis.

Secondary analyses

Next we performed three secondary analyses examining rates of diagnosis for patients admitted to psychiatric units only, by patient age, by treatment setting (hospital size and academic affiliation) to rule out these factors as alternative explanations for the patterns of group differences seen in the original analysis.

For mood disorders, psychotic disorders, substance use, and anxiety disorders, the findings for patients admitted to psychiatric units were very similar to the results of the original analysis of patients in all units. However, as Table 1 shows, the rates of cognitive disorders were very similar between races.

In the analysis that included age as a covariate (Table 1), significantly lower-than-expected rates of cognitive disorders were found for patients under 70 years old of all races. Rates of substance use disorders were higher than expected among African Americans and Caucasians in this age group. For patients 70 years old or older, the proportion of African-American and Caucasian patients with cognitive disorders was significantly larger than expected; rates of substance use disorders for all races were significantly lower than expected. In the remainder of the diagnostic categories, the results were similar to those of the original analysis.

The final analysis, which is not shown in the table, examined diagnostic rates among races by treatment setting—size, academic affiliation, focus, and location. In all treatment settings, the rate of mood disorders among elderly African-American patients was less than half the rate of mood disorders among elderly Caucasian patients; in every setting but the midsize teaching hospital, rates of mood disorders among African-American patients were significantly lower than expected. Although rates of cognitive, psychotic, and substance use disorders among African-American patients varied by treatment site, the rates in midsize and metropolitan teaching hospitals were significantly higher than those among elderly Caucasian patients. The largest proportion of African-American patients was admitted to these settings—40.7 percent of patients admitted to midsize teaching hospitals were African American.

Discussion

To examine differential rates of clinical psychiatric diagnoses between races among inpatients in the VA health system, we compared rates of psychiatric diagnoses between groups of elderly African-American, Hispanic, and Caucasian veterans discharged with primary psychiatric diagnoses in fiscal year 1994. Although age and treatment setting appeared to moderate some of the effects seen in the original analysis, these factors certainly did not appear to account for all the differences in diagnostic rates among the racial groups examined.

Across all analyses, the most striking finding was that of significantly lower rates of mood disorders among elderly African-American patients, compared with elderly Caucasian patients, and, in most cases, elderly Hispanic patients. In every analysis performed, the rate of mood disorders among African-American patients was less than half the rate among Caucasian patients. Also, differences in rates of cognitive, psychotic, and substance use disorders persisted in academically affiliated treatment settings (midsize and metropolitan teaching hospitals), where larger proportions of African-American patients were seen and where presumably diagnoses are more accurate (26).

Fabrega and associates (19) also found lower rates of mood disorder diagnoses among elderly African-American patients than among elderly Caucasian patients. In attempting to explain the differences, these authors listed several factors, including confounding effects of social class, referral bias, misdiagnosis, psychological consequences of racism, and differences in genetic-biological vulnerability. In our study, social class would not appear to be a major factor, given that most veterans eligible for care in the VA system in fiscal year 1994 were likely similar in socioeconomic status. Likewise, referral bias in terms of access to treatment would not seem likely in the VA system. Misdiagnosis is possible, although it is noteworthy that differences in rates of clinical diagnoses were also found in academically affiliated settings, in which greater diagnostic accuracy might be expected (26). Misdiagnosis because of a different presentation of depression among elderly African-American patients than among elderly Caucasian patients is a possibility. Several previous studies examining the presentation of depressive disorders among younger African-American patients have found higher ratings on hostility and irritability and a greater frequency of somatic complaints (1,30,31,32).

In addition, African Americans may demonstrate different patterns of seeking mental health care. African-American elders, having overcome multiple hardships in their earlier years, not only may bring an added resiliency to their older years but also may view some institutions with caution because of previous experiences (33). Depressed African-American patients may use religion and church as an alternative support system (1,30,31,32). Neighbors and Jackson (34) have noted that African Americans may rely more on informal support for some emotional problems. Thus an additional hypothesis that older African Americans may seek formal care for mood disorders such as depression less often than older Caucasians—or they may be less likely to use VA inpatient care for certain types of disorders—might partly explain the lower rates of mood disorder diagnoses among the African-American patients in our study.

The additional possibility of an underlying biological process is suggested by a recent study examining racial differences in neuropsychiatric symptoms among outpatients with dementia (35). This study found significantly higher levels of psychotic symptoms and lower levels of depressive symptoms among blacks than among whites, but no differences in symptoms were found between African Americans and African Caribbeans. The authors concluded that racial differences likely reflect variations in symptom presentation but that the absence of intraracial differences also raised the possibility of an underlying biological or genetic factor.

One final possibility is selective mortality. Although African Americans may have higher death rates than Caucasians before age 75, this phenomenon may be reversed among those over 75 years of age (36,37). It has been suggested that the reversal may represent a process whereby a young, morbid population dies earlier, leaving an older and more select group of survivors (38). Perhaps the survivors are less susceptible to mood disorders.

Although our analysis of all types of units found a significantly higher rate of cognitive disorders among African-American patients than among Caucasian patients, the higher rate was not found when the analyses examined psychiatric units only, patients under age 70, or certain treatment settings, such as small hospitals, general hospitals, or psychiatric hospitals. However, contrary to our expectations, differences in rates of cognitive disorders were also found in academically affiliated treatment settings. Some investigators have suggested that higher rates of dementia diagnoses in African Americans may be related to the effects of education level or the presence of medical comorbidity (39,40).

No clear patterns of differences emerged for the elderly Hispanic patients in our study. Although significantly higher rates of psychosis were found among Hispanic patients than among Caucasian patients in the analyses of all units and of psychiatric units only, the significance of these differences dissipated in the analyses by age group and treatment setting. In the latter analysis, comparisons between Hispanics and the other groups were difficult to make because of the small numbers of Hispanics at many hospital sites. However, the findings for Hispanics are similar to those reported in the National Comorbidity Survey (17), which found no major differences between Hispanics and the general population. They are also similar to findings of a study by Vega and associates (41) in which Mexican Americans were found to have rates of psychiatric disorders similar to those of the national population of the United States. The level of acculturation of Mexican Americans has been reported to influence the report of psychiatric symptoms (42). The Hispanic veterans in our sample would have had to have been in the United States for many years, which may account for the similar diagnostic rates among Hispanics and Caucasians in our study.

Given that all patients studied were veterans and most were men, our results must be interpreted with caution. They cannot be generalized to nonveteran populations with equal numbers of men and women. In addition, use of VA services has been associated with comorbidity, service-connected disability, lack of health insurance, and low income (43), and all patients studied were inpatients. Thus inferences about community prevalence cannot be made from these results. Other limitations to consider in interpreting our results include the retrospective nature of our study, the primarily administrative database used, and the fact that the groups of African-American and Hispanic patients were relatively small compared with the Caucasian patient group.

Conclusions

This study found differential rates of clinical psychiatric diagnoses by race among elderly inpatients in acute units of VA hospitals. This finding is important because it reflects the diagnoses—and perhaps treatment—being given across an extensive health care system treating a large number of minority patients. The finding of significantly lower rates of mood disorder diagnoses among African-American elderly patients in several types of analyses is striking and clearly merits further study.

This study provides new data on race and clinical psychiatric diagnoses of elderly veterans. These differences may be driven both by patient factors, such as different presentations of symptoms or selective use of health services, and by provider factors, such as clinician bias and misdiagnosis.

Dr. Kales is affiliated with the Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center at the Ann Arbor Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Psychiatry Service (116A), 2215 Fuller Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48105 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Kales, Dr. Blow, Dr. Bingham, and Ms. Copeland are with the Serious Mental Illness Treatment Research and Evaluation Center in the health services research and development service at the Ann Arbor VA Medical Center. Dr. Kales, Dr. Blow, Dr. Bingham, and Dr. Mellow are with division of geriatric psychiatry in the department of psychiatry at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

|

Table 1. Race and psychiatric diagnosis among hospitalized elderly veterans in fiscal year 1994, by type of unit and age

1. Adebimpe VR, Hedlund JL, Cho DW, et al: Symptomatology of depression in black and white patients. Journal of the National Medical Association 74:185-190, 1982Medline, Google Scholar

2. Strakowski SM, Lonczak HS, Sax KW, et al: The effects of race on diagnosis and disposition from a psychiatric emergency service. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 56:101-107, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

3. Jones BE, Gray BA: Problems in diagnosing schizophrenia and affective disorders among blacks. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:61-65, 1986Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Strakowski SM, Shelton RC, Kolbrener ML: The effects of race and comorbidity on clinical diagnosis in patients with psychosis. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 54:96-102, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

5. Flaskerud JH, Hu L: Relationship of ethnicity to psychiatric diagnosis. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorders 180:296-303, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Bell CC, Mehta H: The misdiagnosis of black patients with manic depressive illness. Journal of the National Medical Association 72:141-145, 1980Medline, Google Scholar

7. Fabrega H, Mezzich J, Ulrich RF: Black-white differences in psychopathology in an urban psychiatric population. Comprehensive Psychiatry 29:285-297, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Adebimpe VR: Race, racism, and epidemiological surveys. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:27-31, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

9. Strakowski SM, McElroy SL, Keck PE, et al: Racial influence on diagnosis in psychotic mania. Journal of Affective Disorders 39:157-162, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Brown C, Schulberg HC, Madonia MJ: Clinical presentations of major depression by African-Americans and whites in primary care medical practice. Journal of Affective Disorders 41:181-191, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Simon RJ, Fleiss JL, Gurland BJ, et al: Depression and schizophrenia in hospitalized black and white mental patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 28:509-512, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Adebimpe VR: Overview: white norms and psychiatric diagnosis of black patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 138:279-285, 1981Link, Google Scholar

13. Mukherjee S, Shukla S, Woodle J, et al: Misdiagnosis of schizophrenia in bipolar patients: a multiethnic comparison. American Journal of Psychiatry 140:1561-1574, 1983Google Scholar

14. Adebimpe VR, Klein HE, Fried J: Hallucinations and delusions in black psychiatric patients. Journal of the National Medical Association 73:517-520, 1981Medline, Google Scholar

15. Liss JL, Weiner A, Robins E, et al: Psychiatric symptoms in white and black inpatients. Comprehensive Psychiatry 14:475-488, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Robins LN, Regier DA: Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiological Catchment Area Study. New York, Free Press, 1991Google Scholar

17. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8-19, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Mulsant BH, Stergiou A, Keshavan MS, et al: Schizophrenia in late life: elderly patients admitted to an acute care psychiatric hospital. Schizophrenia Bulletin 19:709-721, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Fabrega H, Mulsant BH, Rifai AH, et al: Ethnicity and psychopathology in an aging hospital-based population. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 182:136-144, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Zubenko GS, Rosen J, Sweet RA, et al: Impact of psychiatric hospitalization on behavioral complications of Alzheimer's disease. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:1484-1491, 1992Link, Google Scholar

21. Leo RJ, Narayan DA, Sherry C, et al: Geropsychiatric consultation for African-American and Caucasian patients. General Hospital Psychiatry 19:216-222, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Coleman D, Baker FM: Misdiagnosis of schizophrenia among older, black veterans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 182:527-528, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Baker FM: Misdiagnosis among older psychiatric patients. Journal of the National Medical Association 87:872-876, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

24. Strauss GD, Sack DA, Lesser I: Which veterans go to VA psychiatric hospitals for care: a pilot study. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 36:962-965, 1985Abstract, Google Scholar

25. Rosenheck R, Fontana A: Utilization of mental health services by minority veterans of the Vietnam era. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 182:685-691, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Hirschowitz J, Ayyala M, Krishnamoorthy G, et al: A comparison of hospital charting practice for patients with schizophrenia. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:392-393, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

27. International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification. Ann Arbor, Mich, Commission on Professional and Hospital Activities, 1978Google Scholar

28. Stefos T, Lavallee N, Holden F: Fairness in Prospective Payment: A Clustering Approach. Washington, DC, Veterans Administration, Management Science Group, 1988Google Scholar

29. Von Eye A: Introduction to Configural Frequency Analysis: The Search for Types and Antitypes in Cross-Classifications. New York, Cambridge University Press, 1990Google Scholar

30. Baker FM: Mental health issues in elderly African-Americans. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine 11:1-13, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Husaini BA, Moore ST: Arthritis disability, depression, and life satisfaction among black elderly people. Health and Social Work 25:253-260, 1990Google Scholar

32. Delehanty SG, Dimsdale JE, Mills P: Psychosocial correlates of reactivity in black and white men. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 35:451-460, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Baker FM: Psychiatric treatment of older African Americans. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:32-37, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

34. Neighbors HW, Jackson JS: The use of informal and formal help: four patterns of illness behavior in the black community. American Journal of Community Psychology 12:629-644, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Cohen CI, Magai C: Racial differences in neuropsychiatric symptoms among dementia outpatients. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 7:57-63, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Markides KS: Aging and Health. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage, 1989Google Scholar

37. Wing S, Manton K, Stallard E, et al: The black/white mortality crossover: investigation in a community-based study. Journal of Gerontology 40:78-84, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Gibson RC: The age-by-race gap in health and mortality in the older population: a social science research agenda. Gerontologist 34:454-462, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Henderson AS: The risk factors for Alzheimer's disease: a review and a hypothesis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 78:257-275, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Heyman A, Fillenbaum G, Prosnitz B, et al: Estimated prevalence of dementia among elderly black and white community residents. Archives of Neurology 48:594-598, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, et al: Lifetime prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders among urban and rural Mexican-Americans in California. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:771-778, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Baker FM, Espino DV, Robinson BH, et al: Assessing depressive symptoms in African-American and Mexican-American elders. Clinical Gerontologist 14:15-29, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

43. Rosenheck RA, Massari L: Wartime military service and utilization of VA health care services. Military Medicine 158:223-228, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar