Ethnic Differences in Prediction of Violence Risk With the HCR-20 Among Psychiatric Inpatients

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined ethnic differences in assessment of violence risk among psychiatric inpatients by using the Historical Clinical Risk Management-20 (HCR-20). METHODS: The HCR-20 was administered to 169 consecutive psychiatric inpatients. Individual items and total scores on the HCR-20 were compared between patients of Asian-American (N=51), Euro-American (N=46), and Native-Hawaiian (N=38) heritage. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) and stepwise regressions were calculated for each ethnic group with HCR-20 scores as predictor variables and violent event reports of significant threats and assaults as the outcome measure. RESULTS: Similar rates of overall violence were found between ethnic groups, and the HCR-20 was found to have predictive validity as measured by ROC analysis. Differences in scores on individual HCR-20 items were found, including young age at first incident of violence, psychopathy, early maladjustment, personality disorder, and past supervision failure, as well as total HCR-20 score, with Asian Americans scoring lower (less risk) than Euro-Americans and Native Hawaiians. Stepwise multiple regressions indicated a different pattern of predictor variables for each ethnic group, with impulsivity salient for the Asian-American group, young age at first incident of violence salient for the Euro-American group, and young age at first incident of violence, relationship instability, and risk-management plans' lacking feasibility as salient predictors for the Native-Hawaiian group. CONCLUSIONS: The findings provide preliminary support for the cross-cultural validity of the HCR-20 while at the same time identifying unique ethnic differences in prediction of violence risk among psychiatric inpatients.

There is a growing interest in violence risk assessment for psychiatric inpatients. Accurate risk assessments are particularly important for forensic psychiatric patients, because the decision to discharge a patient is heavily weighted on potential dangerousness to self and others. Risk assessment information is also important for risk management and for developing interventions for risk reduction (1).

One measure that recently has been receiving much attention is the Historical Clinical Risk Management-20 (HCR-20), a rating scale of 20 items that have been found to be predictive of violence according to the violence literature (2). Individual items are scored 0, 1, or 2, and scores are added to yield a total score with a range of 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating a higher risk of violence.

The HCR-20 differs conceptually from its predecessors, including the Violence Risk Appraisal Guide (3) and the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (4), because it incorporates not only static items based on a person's history but also dynamic items that evaluate current clinical presentation and environmental risk factors (5). Studies indicate that the HCR-20 demonstrates good validity for predicting violence for psychiatric patients who are hospitalized (6,7,8,9,10) as well as criminal violence in the community (10,11,12).

One area that has not been fully examined is ethnic differences in violence prediction. Although studies have been conducted in various countries, such as the United Kingdom (6,7), Sweden (8,9,11), Canada (12), and the United States (13), the samples in these studies have been predominantly Caucasians of European heritage. In studies in which persons from other ethnic minority groups are included, the data are reported in aggregate (7,10,13).

This lack of data for non-European-based ethnic groups is of concern given that various indicators have suggested that culture may play a moderating role in violent behaviors and prediction. For example, preliminary epidemiologic data indicate that rates of violence and sexually aggressive behaviors among Asian Americans are generally lower than in other ethnic groups (14,15,16,17). Nationally, arrests for violent crime such as murder, forcible rape, and aggravated assault are four times lower among Asian Americans than in the general population (16). Similarly, statistics on domestic violence in Hawaii have demonstrated lower rates for non-Filipino Asians and higher rates for Euro-Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Filipinos compared with the general population (18). Asian Americans have also demonstrated relatively lower levels of parental aggression toward children and children's counter-aggression toward parents compared with Polynesian and Euro-American families (19).

Other studies indicate that predictors of violence may differ by personal characteristics mediated by ethnicity. Nagayama-Hall and associates (20) reported similar incidents of sexual violence between Asian-American and Euro-American men on the basis of self-report. However, path models revealed differences between the two groups. For Asian-American men, "loss of face" acted as a moderator to reduce sexual violence toward women. This variable was not salient for Euro-American men.

The purpose of the study reported here was to examine whether there are ethnic differences in violence prediction. We believe that the moderating effects of ethnicity are a potentially important issue, because current predictors may not apply to non-Western ethnic groups, or instruments may be less accurate for these groups. Alternatively, different predictors may be more salient for non-Western ethnic groups. If this is true, identifying these predictors may have clinical applications in risk assessment and management with this population. Although relatively small in number, the Asian and Pacific Islander groups are the fastest growing ethnic group in the United States (21). Therefore, information about this group may be useful to all clinicians.

The prediction instrument we used in this study was the HCR-20. The ethnic groups included in the study were Asian Americans, Euro-Americans, and Native Hawaiians. First we compared rates of violence between the ethnic groups. Second, we examined the predictive validity of the HCR-20 for each group. Third, we examined differences in scores on individual HCR-20 items and in the total score. Finally, we examined whether there were differences in violence predictor variables for each ethnic group. We hypothesized that Asian Americans would have a lower rate of violence than Euro-Americans and Native Hawaiians; that there would be differences in the predictive validity of the HCR-20 for each ethnic group; that there would be significant differences in scores for individual HCR-20 items, with Asian Americans scoring lower than both Euro-Americans and Native Hawaiians; and that there would be differences in the pattern of predictor variables of violence between ethnic groups.

Methods

Data were procured retrospectively from the archives of Hawaii State Hospital, which provides psychiatric treatment primarily to forensic patients. The study participants were drawn from 169 consecutive inpatient admissions from February 2002 to January 2003. The various legal statuses of these patients included court-ordered mental evaluation for fitness to stand trial, unfit to proceed on legal charges, acquitted by reason of insanity and committed to a hospital, revocation of conditional release, and transfer from prison for psychiatric stabilization. Forty-eight percent of the patients were charged with felonies, and 52 percent were charged with misdemeanors.

Patients were included in the study if their self-reported ethnicity was Asian American, Euro-American, or Native Hawaiian. The Asian-American group consisted of individuals of Japanese, Chinese, Korean, Filipino, or Vietnamese heritage. All participants who reported some Hawaiian lineage were included in the Native-Hawaiian group. With the exception of Native Hawaiians, participants who were of mixed ethnic heritage—for example, Asian-Euro-Americans—were excluded from the study.

From the original sample, 108 individuals met the inclusion criteria. The breakdown in ethnicity was 41 Asian Americans, 38 Euro-Americans, and 29 Native Hawaiians. The mean±SD age of the sample was 40.1±12.6 years, and the mean educational level was 11.9±2.5 years. The gender breakdown was 88 men and 20 women. DSM-IV diagnosis was based on clinical interview and record review. The diagnostic breakdown was 22 patients with schizoaffective disorder, 14 with paranoid schizophrenia, 14 with methamphetamine-induced psychosis, 12 with psychotic disorder not otherwise specified, 12 with bipolar disorder, 11 with chronic undifferentiated schizophrenia, and 23 with another diagnosis.

All study participants were administered the HCR-20 within a week of admission by three psychologists who were trained at a workshop by the instrument's authors. The interrater reliability for 12 cases was r=.94. The outcome measure was violent episodes as identified by hospital event reports. Types of violence included threats or assaults on patients and staff. All study participants were admitted to the intake unit and were then transferred to one of six other units upon psychiatric stabilization. Three of the units specialized in dual diagnosis issues, two were general psychiatric units, and one housed many patients who had been acquitted and committed for reasons of insanity and who, because of the notoriety of their crimes, were not likely to be discharged in the near future.

Chi square tests were conducted to examine differences in rates of violence. With use of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) procedures, the area under the curve (AUC)—a composite measure of sensitivity and specificity—was calculated at each level of test score. This index determined the accuracy of the HCR-20 in predicting violence in each cultural group. A repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to examine the effects of culture on individual HCR-20 items and overall score. Significance was set at p<.05. However, with a Bonferonni correction, the significance level for the ANOVAs was adjusted to (p<.0025), while the Bonferonni-adjusted significance level was (p<.017) for least-squares difference post hoc tests.

Stepwise multiple regressions were then conducted for each ethnic group with items on the HCR-20 used as predictor variables and number of violent event reports times log10 as the dependent variable. This manipulation was made to control for the skewed distribution of violent events per patient. The level of significance for inclusion was p<.05, and p<.10 was used for exclusion. The study was approved by an internal review board as well as statewide review boards. SPSS was used for data analyses.

Results

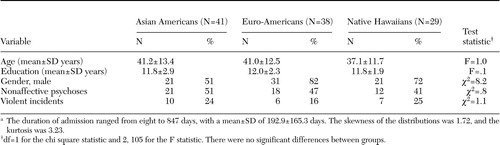

No significant differences were found between the groups in demographic characteristics such as age, gender, and education or in diagnostic characteristics such as the percentage of patients with nonaffective psychotic diagnosis or in the percentage of patients who had engaged in violent acts (Table 1).

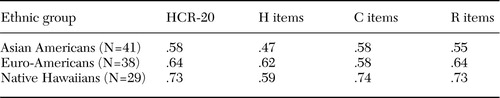

The results of the ROC analysis are presented in Table 2. The AUC was highest for Native Hawaiians (.73) and lowest for Asian Americans (.58), with the Euro-Americans falling in the middle (.64), with no significant differences between the three groups.

The overall model of HCR-20 differences by ethnic group as measured by Wilk's lambda was significant (F=37.44, df=19, 86, p<.001). The main effects of ethnicity was significant (F=12.00, df=2, 105, p<.001, r2=.19) and individual items of the HCR-20 (F=42.39, df=19, 1,995, p<.001, r2=.28) were significant. Of major importance, however, were the significant interaction effects of ethnicity and individual items of the HCR-20 (F=2.18, df=38, 1,995, p<.001, r2=.3). That is, the pattern of significant differences between individual items of the HCR-20 varied across the three ethnic groups.

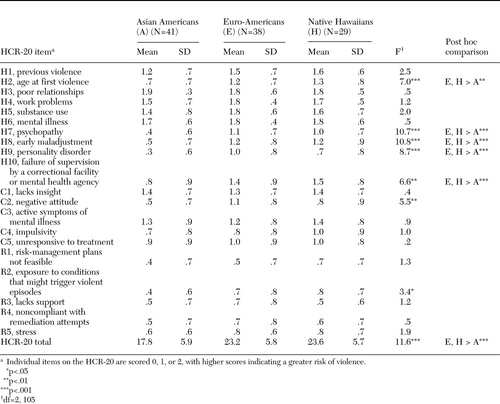

Results of the ANOVAs for individual HCR-20 items by ethnic group are presented in Table 3. Significant results after Bonferroni correction included young age at first incident of violence (F=6.97, df=2, 105, p<.001), psychopathy (F=10.72, df=2, 105, p<.001), early maladjustment (F=10.75, df=2, 105, p<.001), personality disorder (F=8.65, df=2, 105, p<.001), and past supervision failure (on the part of a correctional institution or mental health agency (F=6.64, df=2, 105, p<.002). Total HCR-20 score was also significant (F=11.56, df=2, 105, p<.001).

On post hoc tests, Asian Americans demonstrated significantly lower scores than both Euro-Americans and Native Hawaiians for young age at first incident of violence (p<.002), psychopathy (p<.001), early maladjustment (p<.001), personality disorder (p<.001), past supervision failure (p<.002), and HCR total score (p<.001).

Results of the stepwise multiple regressions were as follows. The predictor variable for Asian Americans was impulsivity (F=7.67, df=1, 40, p<.01, r2=.16). For Euro-Americans, the lone predictor variable was young age at first incident of violence (F=5.35, df=1, 37, p<.05, r2=.13). The two variables for Native Hawaiians included plans' lacking feasibility and relationship instability, with the regression equation accounting for close to half the variance (F=11.98, df=2, 28, p<.005, r2=.43).

Discussion and conclusions

Our findings provide preliminary support for the general hypothesis that ethnicity may play a moderating role in predicting violence in an inpatient psychiatric sample, although support for specific hypotheses was mixed. Contrary to our predictions, we found no differences in rates of institutional violence among the three ethnic groups. This finding runs counter to previous statistics on community sexual and domestic violence for Asian Americans (14,15,16,17,18,19) and suggests that ethnicity as a moderating factor for violence is not a unitary phenomenon and likely differs by type of violence, setting, population, and outcome measure studied.

Our prediction that the HCR-20 would demonstrate a differential predictive accuracy between ethnic groups was also not supported by our data. This finding suggests that HCR-20 has cross-cultural validity in Asian-American, Native-Hawaiian, and Euro-American samples.

Although the HCR-20 was found to demonstrate similar prediction rates for violence among the three ethnic groups, differences were found in scores on individual HCR-20 items and in predictor variables on regression analyses. Asian Americans had significantly lower scores than Euro-Americans and Native Hawaiians on HCR-20 items related to historical factors, including young age at first incident of violence, psychopathy, early maladjustment, personality disorder, and past supervision failure. The results of regression analyses showed that each ethnic group had a unique pattern of predictors and that there were differences in variance between the groups that were accounted for by corresponding models. For Asian Americans the lone predictor was impulsivity, with a small to moderate effect size (r2=.16). The regression for Euro-Americans also had only one predictor—young age at first incident of violence—with a small to moderate effect size (r2=.13). By contrast, the strongest results were demonstrated for Native Hawaiians, for whom we found three salient predictors—young age at first incident of violence, relationship instability, and risk-management plans' lacking feasibility—and a large effect size (r2=.43).

Taken together, our findings suggest that the HCR-20 demonstrates similar predictive accuracy across Asian-American, Native-Hawaiian, and Euro-American samples. However, there are unique ethnic differences in how each group scores on the instrument and in which items are more salient for predicting violence.

Given our preliminary findings, what are the possible cultural explanations for the pattern of salient indicators for violence, and how might these explanations guide treatment? For the Asian-American group, our findings can be explained by the cultural values of interdependence and "saving face," whereby any type of deviance, such as violence, brings shame to the individual and his or her family or group (22). Such values are consistent with lower scores on the HCR-20 items that measure age at first incident of violence, psychopathy, early maladjustment, personality disorder, and past supervision failure. These items relate to behaviors or characteristics that indicate a lack of concern for others and that are highly incongruent with the aforementioned Asian-American values. The lower scores on these items are not surprising given the relatively low rates of violence among Asian Americans (14,15,16,17,18).

A related cultural explanation is the tendency for Asian Americans who seek mental health services to be more severely ill than their Euro-American counterparts who use the same services (23,24). One reason for this difference in help seeking is that many Asian-American families, because of the stigma and shame associated with psychiatric illness, bring family members for psychiatric services only when they become unmanageable (25). It therefore makes sense intuitively that violence among Asian-American psychiatric inpatients would be strongly related to psychiatric symptoms, such as emotional lability. This combination of low scores on items related to historical risk factors and high scores on items related to clinical risk factors suggests that for Asian-American psychiatric inpatients, violence is associated more with aspects of current psychiatric symptoms than with premorbid characteristics.

For both Euro-Americans and Native Hawaiians, violence risk was associated with scores on historical items of the HCR-20, particularly young age at first incident of violence. This finding is more consistent with the results of other studies that have shown that previous violence, particularly violence at a young age, is a strong predictor of future violence (3,26). However, for the Native-Hawaiian participants in our study, relationship instability, or an inability to form stable intimate relationships, and environmental factors as measured by an overall risk management plan, were also significant predictors.

The salience of these factors for predicting violence among Native Hawaiians is consistent with Native Hawaiians' strong values of "aloha" (love and kindness), "ohana" (family), and "lokahi" (harmony) that stress the importance of the relationship between self and others (27) and is also consistent with Native Hawaiians' traditional conceptions of mental illness. Native Hawaiians do not have a word for mental illness; instead, they say "pilikia," or "trouble occurs" (28). Furthermore, emotional and psychological concerns are believed to result from imbalances in key relationships between the person, his or her family, and the natural and spiritual realm (28).

Given these beliefs and values, it makes sense that persons who cannot form stable intimate relationships may be at risk of engaging in violent behaviors. Conversely, it may be that those who are violent within their intimate relationship are particularly prone to violence in general (29). These values also suggest that interactions with the environment, including supports, stressors, destabilizers, and compliance with treatment, are important for determining violence risk among Native Hawaiians.

Ethnic differences in violence risk prediction may also be useful in developing more culture-specific approaches to violence risk reduction. Our findings suggest that, for Asian-American psychiatric patients, interventions that target impulsivity or emotional lability may be a potential strategy for reducing violence risk. By contrast, for Native Hawaiians, interventions that target improvement of interpersonal relationships—for example, hooponopono, an indigenous mental health intervention—may be more effective (27).

In summary, our study provides preliminary evidence that ethnicity plays a moderating role in the prediction of violence among psychiatric inpatients. The possible existence of ethnic differences may be clinically important for more accurate predictions of violence and for the development of more effective intervention strategies for patients from ethnic minority groups. This issue will become more salient as the percentage of individuals from ethnic minority groups in the general population increases in Western societies.

Given the small sample, the uniqueness of the sample, the overrepresentation of men, and the use of ethnicity as a proxy for culture, caution should be taken in generalizing our findings to other Asian and Pacific Islander populations as well as to female populations. Our findings need to be replicated with similar populations located in other psychiatric institutions. The inclusion of cultural identity measures would be useful in obtaining a more pure measure of culture. Incorporating such measures would also control for a possible confounding effect in our study given that many of the patients in the Native-Hawaiian group were of multiple ethnicities, including individuals from Asia and Europe. Another limitation was the use of event reports as a measure of violent events, because this measure may underestimate the actual number of violent events.

We hope this study promotes more research on cultural factors in risk management measures such as the HCR-20 and stimulates clinicians to consider potential cultural effects when making predictions of violence among psychiatric inpatients. Similar studies should include other ethnic groups, such as Hispanics and African Americans, to determine equivalency and examine whether these groups have unique patterns of salient violence predictors on the HCR-20.

Dr. Fujii, Dr. Tokioka, and Dr. Lichton are affiliated with the department of psychology at Hawaii State Hospital, 45-710 Keaahala Road, Kaneohe, Hawaii (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Hishinuma is with the department of psychiatry of the John A. Burns School of Medicine in Oahu, Hawaii. This study was presented at the annual convention of the American Psychological Association, held July 28 to August 1, 2004, in Honolulu.

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of 169 psychiatric inpatients who participated in a study of violence risk assessmenta

aThe duration of admission ranged from eight to 847 days, with a mean±SD of 192.9±165.3 days. The skewness of the distributions was 1.72, and the kurtosis was 3.23.

|

Table 2. Area under the curve (AUC) of scores for total scores on the Historical Clinical Risk Mangement-20 (HCR-20) and for historical (H), clinical (C), and risk-management (R) items, by cultural group

|

Table 3. Analysis of variance of Historical Clinical Risk Mangement-20 (HCR-20) scores by ethnic group

1. Heilbrun K: Prediction versus management models relevant to risk assessment: the importance of legal decision-making consent. Law and Human Behavior 21:347–359,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Webster CD, Douglas KS, Eaves D, et al: HCR-20: Assessing Risk for Violence, Version 2. Vancouver, Canada, Simon Fraser University, 1997Google Scholar

3. Harris GT, Rice ME, Quinsey VL: Violent recidivism of mentally disordered offenders: the development of a statistical prediction instrument. Criminal Justice and Behaviour 20:315–335,1993Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Hare RD: The Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised. Toronto, Multi-Health Systems, 1991Google Scholar

5. Webster DD, Eaves D, Douglas KS, et al: The HCR-20 Scheme: The Assessment of Dangerousness and Risk. Vancouver, Canada, Simon Fraser University and Forensic Psychiatric Services Commission of British Columbia, 1995Google Scholar

6. Gray NS, Hill C, McGleish A, et al: Prediction of violence and self-harm in mentally disordered offenders: a prospective study of the efficacy of HCR-20, PCL-R, and psychiatric symptomatology. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 71:443–451,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Doyle M, Dolan M, McGovern J: The validity of North American risk assessment tools in predicting in-patient violent behaviour in England. Legal and Criminological Psychology 7:141–154,2002Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Dernevik M, Grann M, Johansson S: Violent behaviour in forensic psychiatric patients: risk assessment and different risk-management levels using the HCR-20. Psychology, Crime, and Law 8:93–111,2002Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Strand S, Belfrage H: Comparison of HCR-20 scores in violent mentally disordered men and women: gender differences and similarities. Psychology, Crime, and Law 7:71–79,2001Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Douglas KS, Ogloff JRP, Nicholls TL, et al: Assessing risk for violence among psychiatric patients: the HCR-20 violence risk assessment scheme and the Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 67:917–930,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Tengstrom A: Long-term predictive validity of historical factors in two risk assessment instruments in a group of violent offenders with schizophrenia. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 55:243–249,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Douglas KS, Webster CD: The HCR-20 violence risk assessment scheme: concurrent validity in a sample of incarcerated offenders. Criminal Justice and Behaviour 26:3–19,1999Crossref, Google Scholar

13. McNeil DE, Gregory AL, Lam JN, et al: Utility of decision support tools for assessing acute risk of violence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 71:945–953,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Segal UA: A pilot exploration of family violence among nonclinical Vietnamese. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 15:523–533,2000Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Chen SA, True RH: Asian/ Pacific Island Americans, in Reason to Hope: A Psychosocial Perspective on Violence and Youth. Edited by Eron LD, Gentry JH, Schlegel P. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1994Google Scholar

16. Federal Bureau of Investigation: Uniform Crime Reports for the United States, 2002, Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 2002Google Scholar

17. Koss MP, Gidycz CA, Wisniewski N: The scope of rape: incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of higher education students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 55:162–170,1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Campbell B: A police officer's view of domestic violence. Hawaii Medical Journal 55:171–172,1996Medline, Google Scholar

19. Hartz DT: Comparative conflict resolution patterns among parent-teen dyads of four ethnic groups in Hawaii. Child Abuse and Neglect 19:681–689,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Nagayama-Hall GC, Sue S, Narang DS, et al: Culture-specific models of men's sexual aggression: intra- and interpersonal determinants. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 6:252–267,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. The Asian population:2000. Census brief C2KBR/01–16. Washington, DC, US Bureau of the Census,2002Google Scholar

22. Nagayama-Hall GC: Culture-specific ecological models of Asian American violence, in Asian American Psychology. Edited by Nagayama-Hall GC. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2003Google Scholar

23. Durvasula RS, Sue S: Severity of disturbance among Asian American outpatients. Cultural Diversity and Mental Health 2:43–52,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Sue S: Community mental health services to minority groups: some optimism, some pessimism. American Psychologist 32:616–624,1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Sue DW, Sue D: Counseling the Culturally Different. New York, Wiley, 1999Google Scholar

26. Thornberry TP, Jacoby JE: The Chronically Insane. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1979Google Scholar

27. Rezentes WC: Ka Lama Kukui Native Hawaiian Psychology: An Introduction. Honolulu, A'Alii Books, 1996Google Scholar

28. Lee E: Meeting the Mental Health Needs of Asian and Pacific Islander Americans. Alexandria, Va, National Technical Assistance Center for State Mental Health Planning, 2002Google Scholar

29. Gondolph EW: Who are those guys? Towards a behavioral typology of batterers. Violence and Victims 3:187–203,1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar