The Role of Afro-Canadian Status in Police or Ambulance Referral to Emergency Psychiatric Services

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study tested the hypothesis that among patients admitted to a hospital with psychosis, Afro-Canadian patients would be more likely than Euro-Canadian or Asian-Canadian patients to be brought to emergency services by police or ambulance. METHODS: Data on psychotic patients admitted to the psychiatry ward in 1999 were extracted from records of a general hospital in Montreal. Logistic regression models examined the relationship between being Afro-Canadian and being brought to the emergency service by police or ambulance, while controlling for age, gender, marital status, and number of psychotic symptoms. RESULTS: Of the 351 patients with psychosis, 59 percent were Euro-Canadian, 11 percent were Afro-Canadian, and 18 percent were Asian Canadian. Most Afro-Canadian patients in the study were immigrants from the Caribbean and Africa. Being Afro-Canadian was independently and positively associated with police or ambulance referral to emergency services. CONCLUSIONS: Afro-Canadians admitted to the hospital with psychosis are overrepresented in police and ambulance referrals to emergency psychiatric services.

A growing body of research has suggested that referral patterns to emergency psychiatric services vary by ethnoracial status. For example, in the United Kingdom whites and Asians with psychosis are typically referred to a hospital by family or caregivers, whereas blacks with psychosis tend to be referred by the police (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11).

A small body of research from North America has examined this issue, although most studies have evaluated outpatient or community mental health services rather than referral to urgent hospital care. Studies have found that compared with white Americans, black Americans stay in treatment for less time (12), receive more inpatient care and have poorer mental health outcomes (13), are more often referred to mental health care by police (14) or the justice system (15), have more severe psychopathology on admission (14), are more often admitted urgently (14,15), are less likely to use formal mental health services (15,16), are prone to mistrust their therapists (17), and are high users of self-help agencies (18). In the United States many health practices and outcomes vary by race or ethnicity, but once study data are adjusted for these variables, they frequently are not examined further (19,20). Researchers may distance themselves from potentially controversial research and findings because of the sensitive nature of race relations in the United States (21).

The British literature has not explained the excess of black Britons referred by police to emergency psychiatric services (22), but some investigators have hypothesized that delayed help seeking by black Britons and their families may be a key factor that predisposes them to police contact and eventual referral (23,24,25). Delayed help seeking may lead to a greater number or severity of psychotic symptoms and to a more forceful response from social agencies to contain disruptive behaviors. There are many reasons that explain why black Britons may not seek timely psychiatric treatment. Real or perceived bias in the assessment and treatment of black Britons by predominantly white health care providers may promote distrust of medical services. McGovern and Hemmings (26) found that blacks viewed psychiatric services as racist and rated their care as inferior to that of white patients. Parkman and colleagues (27) found that young British-Caribbean patients with psychosis were profoundly dissatisfied with virtually every aspect of mental health services. The authors suggested that this dissatisfaction arose from the fact that black Britons were excluded from mainstream British society and that mental health services did not address their needs. These issues may contribute to delays in seeking treatment among members of this population.

Canada does not have a widely known history of domestic slavery or widespread colonial activity overseas; therefore, race relations in Canada lack the historical tension that may be observed in the United Kingdom and the United States. Many Canadians perceive their country to be tolerant and relatively free of discrimination, and the Canadian government officially endorses a multicultural society (28). The lack of Canadian data that assesses pathways to emergency psychiatric services by groups of different races or ethnicities may reflect a complacent belief that such matters are of little importance because differences do not exist (29).

The study reported here used a retrospective chart review to test the hypothesis that among patients admitted to the hospital with psychosis, Afro-Canadian patients would be more likely than Euro-Canadian or Asian-Canadian patients to have been brought to emergency services by police or ambulance after the analyses controlled for age, gender, marital status, and number of psychotic symptoms.

Methods

Setting and sample

The sample was drawn from persons admitted to the emergency department of a community hospital serving an inner-city, multiethnic neighborhood in Montreal, Quebec. The area had a high proportion of recent immigrants to Canada.

In 1999 the emergency department had 55,197 patient visits. Of these, 1,661 were referred for psychiatric consultation, of which a further 681 were either admitted directly to the psychiatry ward (614 patients) or transferred to other hospitals with the intent to admit (67 patients) (unpublished data, Unger B, 1999). For all cases, only the most recent admission or transfer was included in the study. After deleting repeat admissions or transfers for the same individual, a total of 517 cases were available for review.

Measures and procedures

The hospital research ethics committee approved this study. Once approval was obtained, charts for the 517 identified cases were reviewed, and research assistants used structured forms to collect sociodemographic and clinical information. The first author checked 20 cases for accuracy of the variables collected and monitored data collection. There was acceptable agreement between the research assistants and the first author for relevant variables (kappa coefficient=.95 for age, kappa=1.0 for gender, kappa=.90 for marital status, and kappa=.85 for mode of admission). Agreement for the number of psychotic symptoms was not possible because the variable was a composite of 18 other variables, but the following data on agreement were available for core psychotic symptoms, all of which were included in number of psychotic symptoms: the kappa coefficients were .90 for presence of hallucinations, .80 for presence of delusions, .50 for presence of paranoid ideation, and .80 for presence of thought disorder. Agreement on ethnoracial status and presence of psychosis was not examined because only the first author determined these variables.

Determination of the presence of psychosis. Emergency psychiatric diagnoses are unreliable, and the accepted criteria for judging the presence of psychosis are unevenly applied by clinicians in the acute setting (30). For these reasons, a retrospective measure of the presence of psychosis for each patient was constructed on the basis of data gathered from the index emergency visit and the resulting psychiatric admission. Patients were identified as psychotic if the chart recorded the presence of at least one of four psychotic symptoms (hallucinations, delusions, paranoid ideation, and thought disorder) or grossly disorganized or inappropriate behavior. To qualify as having grossly disorganized or inappropriate behavior, there had to be evidence of catatonic excitement or immobility, purposeless behavior, inappropriate or bizarre affect, stereotypies, mutism, or other symptomatic behavior. Any patient with one of the five symptoms was judged to have been psychotic, a definition consistent with DSM-IV (31). As a result of this procedure, 351 of the original 517 patients were judged to have been psychotic at the time of hospital admission or transfer. These cases were suitable for use in statistical analyses.

Determination of ethnoracial status. Ethnoracial status was estimated on the basis of information abstracted from the chart. Final decisions about coding the variables for ethnoracial status were made by the first author and were informed by relevant data for each patient: recorded ethnoracial status, languages spoken, country of origin, immigrant status, religion, and family name. Cases that remained ambiguous were assigned to the "unknown" category.

Determination of police or ambulance referral to the emergency department. Official reports in the patient charts indicated whether the patients were brought to the emergency department by police or ambulance. Data were recorded dichotomously (yes, brought in by the police or an ambulance, or no, brought in by another mode of admission).

Severity of psychosis. To construct a rough index of severity of psychosis, symptoms were recorded systematically during the course of data collection, and the sum of these yielded a number between 0 and 18 for each patient. This variable included the presence of five symptoms of psychosis (hallucinations, delusions, paranoid ideation, thought disorder, and grossly bizarre behavior) and 13 associated symptoms or characteristics (a diagnosis of psychotic disorder by the emergency psychiatrist, a hospital discharge diagnosis of psychotic disorder, blunted or inappropriate affect, poor insight, disorientation, poor judgment, self-neglect, poor motivation, impulsive behavior, violent or threatening behavior, a history of recent antipsychotic use, agitation, and grandiosity). Each item was given a value of one point; severity of individual items was not weighted.

Data analysis

Contingency tables (chi square analyses) were used to compare the different ethnoracial groups on categorical variables. Analysis of variance was used to compare continuous variables among the same groups. Logistic regression models controlled for potential confounders and were used to examine whether ethnoracial status predicted police or ambulance referral to emergency services. SPSS 10.0 for Macintosh, standard version, was used for all statistical calculations.

Results

Sample characteristics

Of the 351 patients in the study, the mean±SD age was 44±16.24 years. A total of 184 patients (52 percent) were female, 91 (26 percent) were married, and 50 (14 percent) were employed. A total of 207 patients (59 percent) were Euro-Canadian, 37 (11 percent) were Afro-Canadian, 62 (18 percent) were Asian Canadian, five (1 percent) were Hispanic Canadian, and 40 (11 percent) were of unknown ethnicity. Most Afro-Canadians (31 patients, or 84 percent) were immigrants from the Caribbean and Africa. Most Asian Canadians (59 patients, or 95 percent) were immigrants as well. Thirty-four patients (10 percent) had difficulty speaking English or French. Twenty-one Asian Canadians (34 percent) could not speak English or French, compared with six Euro-Canadians (3 percent).

Comparison of ethnoracial groups

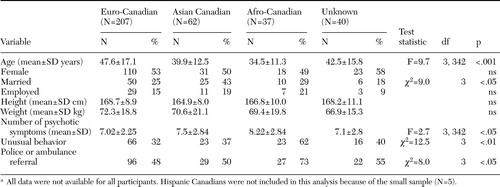

Table 1 shows the results of chi square analysis and analysis of variance among Euro-Canadians, Afro-Canadians, Asian Canadians, and persons whose ethnicity was unknown. Hispanic Canadians were not included in this analysis because the small sample of the group (N=5) made it difficult to interpret the results of chi square analyses. Compared with patients from one or more of the other groups, Afro-Canadian patients were younger, exhibited more psychotic symptoms, had a higher rate of unusual behavior at the time of emergency department presentation, and had a higher rate of police or ambulance referral to the emergency department. Post hoc (Scheffé) tests revealed that Asian and Afro-Canadians were younger than Euro-Canadians (p<.05), but differences among the four groups with respect to number of psychotic symptoms were not significant. Asian Canadians were more likely to be married than members of the other groups.

Multivariate analysis

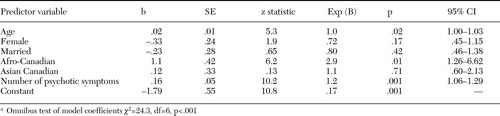

Table 2 presents a multivariate logistic regression model for predicting whether patients would be referred to emergency services either by the police or ambulance or by another means, while controlling for age, gender, marital status, ethnoracial status, and number of psychotic symptoms. A test of the full model with all six predictors against a constant-only model was highly significant (p<.001), indicating that the predictors as a set reliably distinguish between the two methods of referral to emergency psychiatric services. Predictor variables were chosen that would have been present before contact by police or ambulance—that is, factors that may have influenced the patient's referral to psychiatric services. Of these, a higher number of psychotic symptoms was independently associated with police or ambulance referral, as was being Afro-Canadian, and an older age. Coefficients of the predictor variables (b) are positive when the relationship between the predictor and dependent variable is direct and are negative when there is an inverse relationship. Hence, being female yielded lower, although statistically insignificant, odds of being brought to psychiatric services by police or ambulance. Because of the large number of missing values, height and weight were not included in the final analysis.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first Canadian study to suggest that Afro-Canadians hospitalized with psychosis are more likely than other patients to have been brought to emergency psychiatric services by police or ambulance. Although many individuals with psychosis attract the attention of police or the ambulance authority, the association between being Afro-Canadian and being referred by police or ambulance raises a number of complex issues. For example, in this study Afro-Canadian patients were judged to have more psychotic symptoms and to exhibit more unusual behavior than patients from the other groups (Table 1). Strakowski and colleagues (32) found similar results when comparing levels of psychotic symptoms among African-American and white patients in Cincinnati. At the same time, researchers in the United States and the United Kingdom have suggested that black patients delay seeking help because of distrust of psychiatric services, denial of the presence of mental illness, or a combination of the two (24,26,2733,34,35,36). Distrust of psychiatric services by black patients remains a possible precursor of delays in seeking help, severe clinical presentation, and urgent referral to emergency services. It is notable that few studies on this topic exist in Canada, a fact that may reflect a complacency that is long overdue for being challenged.

Denial of psychosis may be common among some black populations (35,36). Individuals with poor insight may be more likely to deny the presence of illness, thereby leading to delayed treatment, severe clinical presentation, and urgent referral to psychiatric services. The data from our study allowed for only a crude estimate of insight. Presence or absence of insight was determined by psychiatric evaluation in the emergency department. The proportion of Afro-Canadian patients with poor insight was not significantly different than that of Asian Canadians. In addition, after the analyses controlled for poor insight, being Afro-Canadian remained significantly associated with police or ambulance referral to emergency psychiatric services (data available on request). Therefore, denial of psychotic illness that led to delays in seeking help does not appear to account for the overrepresentation of Afro-Canadians referred by police or ambulance in this study.

Language barriers could also contribute to delays in seeking help, which could result in increased rates of police or ambulance referral. In the study reported here, language barrier was most often an issue for Asian Canadians; yet being Asian was not associated with police or ambulance referral. Controlling for language barrier in logistic regression models did not change the reported outcomes (data available on request), although the small sample may have precluded finding an effect.

Taking a broader view, the findings of this study raise the possibility that persons of African decent experience negative pathways to psychiatric care even where overt racial tension is minimal, such as in Canada. These findings point away from blatant bigotry and prejudice as determinants of the mode of referral to emergency psychiatric services and toward complex webs of disadvantage arising from life in societies that devalue individuals on the basis of skin color. Perhaps there are common factors shared by blacks living in Eurocentric countries, such as social adversity (37), that predispose them to undesirable modes of referral to emergency services. An important point for future study would be to clarify the sources of disadvantage among blacks and explain how they establish and maintain barriers to mental health care.

The results of this study were based on retrospective chart review of a small sample, and all conclusions must be interpreted with caution. However, one strength of the retrospective design of the study was that it assessed practices and attitudes as they were recorded; that is, the assessment was unaffected by the heightened self-awareness that may occur under a research protocol. Although it was possible to determine a specific ethnoracial status for most patients, the categories were heterogeneous. For example, the Euro-Canadian category contained patients with backgrounds from Europe, North America, Israel, North Africa, Greece, and Italy. The Afro-Canadian and Asian-Canadian categories were also diverse, comprising individuals from many ethnic and cultural origins who were grouped on the basis of skin color, geographic proximity of country of origin, and religion. The use of more precise and socially meaningfully categories would depend on establishing systematic methods of recording patients' ethnic and cultural status.

A final limitation was the lack of a standard measure of severity of psychosis. Common clinical measures of severe presentation, such as the Global Assessment of Functioning, were infrequently recorded in the emergency psychiatric consultation. In an attempt to partially remedy this problem, an index of severity of psychosis was constructed by tallying the number of psychotic symptoms for each patient. The main shortcoming of this approach was that the severity of individual symptoms remained unknown. When variables that could estimate severity of clinical presentation (presence of unusual behavior, presence of impaired insight, presence of agitation or threatening behavior) were used in place of number of psychotic symptoms for some regression models, the principal outcomes did not change. However, until the severity of psychosis can be formally assessed, such as in a prospective study, it remains a possible confounding variable.

Conclusions

In summary, the results of this study suggest that in Montreal, Canada, Afro-Canadian patients admitted to the hospital with psychosis are more likely to be brought to emergency psychiatric services by police or ambulance than their Euro-Canadian or Asian-Canadian counterparts. This finding cannot be explained by age, gender, marital status, or number of psychotic symptoms. The reasons for these findings remain poorly understood, but they may have to do with help-seeking behaviors that set in motion a cascade of events that links interventions to specific ethnoracial groups. For example, when African or Caribbean immigrants to Canada learn that police and ambulance contact are frequent among members of their community, the entire judicial and medical establishments may come under suspicion. Individuals may delay seeking help from these institutions, resulting in longer duration of untreated psychosis and relatively severe symptoms that require urgent measures to contain. On the other hand, an increased police presence in the Afro-Canadian community may prime families to call the police to resolve disputes or control disruptive persons. Efforts to understand these issues may be advanced through two important lines of research: an assessment of delayed treatment by ethnoracial status and the use of qualitative methods to understand the processes leading to urgent referral to psychiatric services.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Metropolis Project and the Fond de Recherche en Santé du Québec.

All authors except Dr. George K. Jarvis are affiliated with the culture and mental health research unit at Jewish General Hospital, 4333 Cote Street, Catherine Road, Montreal, Quebec, Canada H3T 1E4 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Kirmayer is also with the division of social and transcultural psychiatry at McGill University in Montreal. Dr. George K. Jarvis is with the department of sociology at the University of Hawaii in Honolulu.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 351 patients admitted to the hospital for psychosis, by ethnoracial statusa

aAll data were not available for all participants. Hispanic Canadians were not included in this analysis because of the small sample (N=5)

|

Table 2. Predictors of police or ambulance referral to emergency psychiatric services among patients admitted to the hospital for psychosis (N=317)aaOmnibus test of model coefficients χ2=24.3, df=6, p<.001

1. Hitch PJ, Clegg P: Modes of referral of overseas immigrant and native-born first admissions to psychiatric hospitals. Social Science and Medicine 14A:369–374,1980Google Scholar

2. Harrison G, Ineichen B, Smith J, et al: Psychiatric hospital admissions in Bristol: social and clinical aspects of compulsory admission. British Journal of Psychiatry 145:605–611,1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Dunn J, Fahy TA: Police admissions to a psychiatric hospital: demographic and clinical differences between ethnic groups. British Journal of Psychiatry 156:373–378,1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Owens D, Harrison G, Boot D: Ethnic factors in voluntary and compulsory admissions. Psychological Medicine 21:185–196,1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Perera R, Owens DG, Johnstone EC: Disabilities and circumstances of schizophrenic patients—a follow-up study. British Journal of Psychiatry 13(suppl):40–46,1991Google Scholar

6. Thomas CS, Stone K, Osborn M, et al: Psychiatric morbidity and compulsory admission among UK-born Europeans, Afro-Caribbeans, and Asians in Central Manchester. British Journal of Psychiatry 163:91–99,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Burnett R, Mallett R, Bhugra D, et al: The first contact of patients with schizophrenia with psychiatric services: social factors and pathways to care in a multi-ethnic population. Psychological Medicine 29:475–483,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Commander MJ, Cochrane R, Sahidharan SP, et al: Mental health care for Asian, Black, and White patients with non-affective psychoses: pathways to the psychiatric hospital, in-patient and after care. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 34:484–491,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Goater N, King M, Cole E, et al: Ethnicity and outcome of psychosis. British Journal of Psychiatry 175:34–42,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Coid J, Kahtan N, Gault S, et al: Ethnic differences in admissions to secure forensic psychiatric services. British Journal of Psychiatry 177:241–247,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Audini B, Lelliott P: Age, gender, and ethnicity of those detained under Part II of the Mental Health Act 1983. British Journal of Psychiatry 180:222–226,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Sue S, McKinney H, Allen D, et al: Delivery of community mental health services to black and white clients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 42:794–801,1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Sue S: Community mental health services to minority groups: some optimism, some pessimism. American Psychologist 32:616–624,1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Goodman A, Siegel C: Differences in white-nonwhite community mental health center service utilization patterns. Journal of Evaluation and Program Planning 1:51–63,1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Hoberman H: Ethnic minority status and adolescent mental health services utilization. Journal of Mental Health Administration 19:246–67,1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Pagdett D, Patrick C, Burns B, et al: Ethnicity and the use of outpatient mental health services in a national insured population. American Journal of Public health 84:222–226,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Whaley AL: Cultural mistrust of white mental health clinicians among African Americans with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 71:252–270,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Theriot M, Segal S, Cowsert M: African-Americans and comprehensive service use. Community Mental Health Journal 39:225–237,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Jones CP: Race, racism, and the practice of epidemiology. American Journal of Epidemiology 48:629–637,2001Google Scholar

20. Williams D: the concept of race in health services research. Health Services Research 29:261–74,1994Medline, Google Scholar

21. Feagin JR: Racist America: Roots, Current Realities, and Future Reparations. New York, Routledge, 2000Google Scholar

22. Morgan C, Mallett R, Hutchinson G, et al: Negative pathways to psychiatric care ad ethnicity: the bridge between social science and psychiatry. Social Science and Medicine 58:739–752,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Bhugra D, Bhui K: Racism in psychiatry: paradigm lost—paradigm regained. International Review of Psychiatry 11:36–243,1999Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Harrison G: Ethnic minorities and the Mental Health Act. British Journal of Psychiatry 180:198–199,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Emsley RA, Roberts MC, Rataemane S, et al: Ethnicity and treatment response in schizophrenia: a comparison of 3 ethnic groups. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 63:9–14,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. McGovern D, Hemmings P: A follow-up of second generation Afro-Caribbeans and white British with a first admission diagnosis of schizophrenia: attitudes to mental illness and psychiatric services of patients and relatives. Social Science and Medicine 38:117–127,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Parkman S, Davies S, Leese M, et al: Ethnic differences in satisfaction with mental health services among representative people with psychosis in South London: PRiSM Study 4. British Journal of Psychiatry 171:260–264,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Reitz GR, Breton R: Prejudice and discrimination in Canada and the United States: a comparison. In Racism and Social Inequality in Canada: Concepts, Controversies and Strategies of Resistance. Edited by Satzewich V. Toronto, Thompson Educational Publishing, Inc, 1998Google Scholar

29. Henry F: Race relations research in Canada today: a "state of the art" review. Presented at the Canadian Human Rights Commission Colloquium on Racial Discrimination, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, Sept 25, 1986Google Scholar

30. Way BB, Allen MH, Mumpower JL, et al: Interrater agreement among psychiatrists in psychiatric emergency assessments. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:1423–1428,1998Link, Google Scholar

31. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

32. Strakowski SM, Flaum M, Amador X, et al: Racial differences in the diagnosis of psychosis. Schizophrenia Research 21:117–124,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Sashidaran SP: Institutional racism in British psychiatry. Psychiatric Bulletin 25:244–247,2001Crossref, Google Scholar

34. Whaley AL: Ethnicity/race, paranoia, and hospitalization for mental health problems among men. American Journal of Public Health 94:78–81,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Perkins RE, Moodley P: Perception of problems in psychiatric inpatients: denial, race, and service usage. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 28:189–193,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Johnson S, Orrell M: Insight, psychosis, and ethnicity: a case-note study. Psychological Medicine 26:1081–1084,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Cantor-Graae E, Selten JP: Schizophrenia and migration: a meta-analysis and review. American Journal of Psychiatry 162:12–24,2005Link, Google Scholar