The Content and Clinical Utility of Psychiatric Advance Directives

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This paper provides the first systematic examination of the content and clinical utility of psychiatric advance directives, which are documents that specify treatment preferences in advance of periods of compromised decision making. METHODS: Directives were completed by 106 community mental health center outpatients with at least two psychiatric hospitalizations or emergency department visits within two years. Participants used AD-Maker software in groups of up to six people led by peer trainers. Clinical utility was defined as the degree to which instructions are clinically feasible, useful, and consistent with standards of care. RESULTS: Fifty-five percent of participants were female, and 24 percent were nonwhite. Their mean±SD age was 42±9.1 years. Primary diagnoses included schizophrenia spectrum disorders (44 percent), bipolar disorders (27 percent), major depression (22 percent), and other disorders (7 percent). Eighty-one percent of participants listed preferred medications, most often antidepressants and second-generation antipsychotics, and 64 percent listed medications they would refuse, most commonly first-generation antipsychotics. Sixty-eight percent preferred hospital alternatives over hospitalization, 89 percent specified methods of deescalating crises, and 72 percent indicated that they would refuse electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Forty-six percent appointed a surrogate decision maker. Fifty-seven percent desired a directive that is irrevocable during periods of incapacity. Instructions were rated as feasible, useful, and consistent with practice standards for at least 95 percent of the advance directives, with the exception of instructions about the willingness to use medications not specifically listed in the directive. CONCLUSIONS: Results suggested that psychiatric advance directives provide a wealth of treatment preference information that is almost uniformly considered clinically useful. Although the utility of advance directives may vary depending on the circumstances of specific crisis episodes, the information provided can expedite and strengthen clinical care.

Psychiatric advance directives document patients' treatment preferences and, if desired, a surrogate decision maker in advance of periods of symptom exacerbation and compromised decision making (1,2,3,4). Advance directives provide a means to recognize treatment preferences when meaningful patient participation in treatment decisions would otherwise be unlikely (5,6,7,8). Such recognition may decrease perceived coercion and increase treatment collaboration, motivation for treatment, and treatment adherence (3,4,9,10,11). Advance directives may also improve crisis intervention by identifying resources to deescalate crises and to serve as viable alternatives to hospitalization, which may, in turn, reduce hospitalizations (3,12,13,14).

We know little about the content and clinical utility of psychiatric advance directives, although this information is important for anticipating individual treatment needs and for broader service planning. For example, while one person's directive instructions about alternatives to hospitalization and methods of deescalating crises may shape care at the individual level, patterns of such instructions may prompt development of crisis services and policies. In the 18 states with statutes about psychiatric advance directives, content parameters for the document are spelled out, typically permitting instructions about psychotropic medications, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), hospital admission, and appointment of surrogate decision makers. Some states also permit instructions about crisis interventions and about individuals to notify of hospital admission (15,16).

Very limited information has been reported about the content of completed psychiatric advance directives. Within a small community mental health sample (N=30), no directives were used to refuse all treatment, although refusal of ECT was included in 17 directives (57 percent), and eight (27 percent) included refusal of haloperidol (7). In a similar sample (N=54), two participants (4 percent) refused all psychotropic medications. In these samples, most people (66 percent to 82 percent) appointed a surrogate decision maker (7).

Clinical utility of psychiatric advance directives can be defined as the extent to which specified instructions are feasible, useful, and consistent with standards of care. For example, instructions that indicate refusal of all psychotropic medications would generally not be consistent with standards of care for individuals with serious and persistent mental illnesses. Such instructions would have low clinical utility because of the clinical challenges they present, although they may nevertheless be enforceable (see Hargrave v. State of Vermont). In contrast, information about patients' preferences among second-generation antipsychotic medications may have high clinical utility. Similarly, instructions to provide crisis services that are unavailable would have low clinical utility because of the infeasibility of providing such services; however, preferences among available services would be very useful. The clinical utility of psychiatric advance directives has bearing on whether the documents are viewed as helpful, superfluous, or a hindrance to the provision of clinical care as well as service and policy development. Thus this paper provides the first systematic examination of the content and clinical utility of psychiatric advance directives.

Methods

Participants and settings

Participants were enrolled in ongoing services at two community mental health centers in Washington State. At the time of the study (2001-2003), Washington State did not have laws specifically addressing psychiatric advance directives; however, the state's broader health care advance directive laws were considered to apply.

Participant selection and recruitment protocols were approved by the University of Washington institutional review board. By using electronic records, a pool of 475 potential participants were identified as being 18 years of age or older and having at least two psychiatric emergency services or hospitalizations within two years. Of those potential participants, 172 were ineligible for study participation: 158 could not be contacted largely because of long-term hospitalization or incarceration, six were unable to provide informed consent, six were unable to participate in research interviews in English, and two were too agitated to be approached about the study. Of the remaining 303 eligible individuals, 133 were interested in completing an advance directive and provided informed consent for study participation. Twenty-seven individuals withdrew from the study before completing a directive, yielding 106 individuals who completed advance directives.

Procedures

Participants completed advance directives in groups of up to six people. Groups were led by a peer trainer who provided an overview of instructions, the documents' legal status, and potential benefits and challenges to their use. The peer trainer and research assistants provided assistance to participants if it was requested or believed to be needed.

Participants created psychiatric advance directives by using individual laptop computers loaded with the AD-Maker software (17). The program communicated information by using both written information on the computer screen and a concurrent voice-over. Users selected responses by using a mouse. The program began with a short tutorial about the nature and use of psychiatric advance directives. It then required the user to complete a set of six true or false questions to assess competency to complete a directive, although this competency is also a legal presumption (16). The user had to answer four of the six questions correctly to proceed. If the user failed, the program displayed key concepts again and presented a new set of six questions. If at least four of six questions were not answered correctly by the third attempt, the program did not allow the user to proceed and asked him or her to try again on a different day.

The AD-Maker then "interviewed" the user about his or her preferences in five treatment areas and five nontreatment areas; users could specify instructions in as many areas as they wished. The five treatment areas were psychotropic medications; hospital preferences; alternatives to hospitalization; emergency deescalation methods, including rank-ordered preferences among seclusion, seclusion plus restraint, and sedating medication; and ECT. Reasons for preferences were also selected from established options. The five nontreatment personal care areas were persons to notify of hospitalization; persons not authorized to visit during hospitalization; assistive devices to retain during hospitalization; dietary preferences; and persons to contact to take care of finances, dependents, and pets during hospitalization. Users were then given the option of appointing a surrogate decision maker and also of specifying any other instructions in a narrative format.

Users were also given options about when to activate the directive and whether they would like the directive to be revocable at any time or only when they have not lost decision-making capacity. The AD-Maker used a decision-tree structure in which responses to multiple-choice questions determine which additional information and questions were presented to participants, thereby reducing the amount and complexity of information that must be processed (17).

The AD-Maker provided guidance to users in two areas. First, although the program allowed users to select refusal of all psychotropic medications, it suggested, by flashing the response option, that permitting some psychotropic medications was preferable. In addition, users were required to rank-order preferences among seclusion, seclusion plus restraint, and sedating medication rather than refusing any of these emergency interventions.

Instruments

Clinical utility of each AD-Maker content area was rated on 3-point Likert scales about consistency with practice standards, feasibility, and usefulness. The scales were modified from a recently developed instrument (18). Because of a lack of variance, these scales were recoded as dichotomous—consistent or inconsistent, feasible or infeasible, and useful or not useful.

Data collection and statistical analysis plan

Content analysis. Data elements were derived to indicate the presence or absence of instructions for each AD-Maker content area as well as responses within content areas. One research team member initially determined categorical codes for responses to open-ended questions, which a second team member independently coded. Team members discussed discrepancies until an agreement was reached.

Clinical utility analysis. Clinical utility ratings were completed by a third-year psychiatry resident at the University of Washington Medical School, who had more than ten years of clinical experience with the population under study. To determine the reliability of the ratings, an attending psychiatrist at the same facility also rated a randomly selected sample of 20 directives. Ratings were made with reference to each participant's primary psychiatric diagnosis, the context of available services, and usual care within the public mental health system in which participants received services. Ratings were based on experience with typical psychiatric crises, because it was infeasible to conduct ratings during an actual psychiatric crisis for each participant. Because of a lack of variability, percentage exact agreement was calculated rather than kappa coefficients. Exact agreement was over 90 percent for all ratings, with the exception of instructions about willingness to try medications not listed in the directive (67 percent), ECT (73 percent), people not authorized to visit during hospitalization (70 percent), and "other" narrative instructions (73 percent).

Two research team members independently entered data and then matched the data within SPSS/Windows to detect discrepancies. Team members discussed discrepancies until an agreement was reached. Descriptive analyses were conducted in SPSS/Windows 11.0.1.

Results

Participant make-up

Of the 106 participants, 58 were women (55 percent), and 25 were nonwhite (24 percent). Participants' mean±SD age was 42±9.1 years. Forty-seven (44 percent) had a primary diagnosis within the schizophrenia spectrum, 28 (27 percent) had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, 23 (22 percent) had a diagnosis of major depression, and eight (7 percent) had other diagnoses. Forty-eight (45 percent) also had a substance use diagnosis, and 39 (37 percent) had a personality disorder diagnosis. The mean score on the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) (19) was 30.7±9.1. There were no significant differences between participants (N=106) and eligible nonparticipants (N=197) with respect to gender, race, age, diagnosis, or GAF score.

Treatment preferences

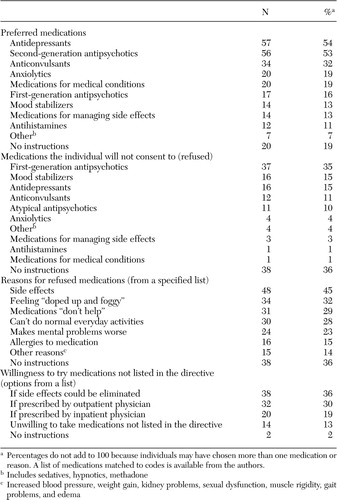

Psychotropic medication. Eighty-six participants (81 percent) listed specific preferred medications, 68 (64 percent) listed medications they would refuse, and no one rejected all psychotropic medications. Participants generated their own lists of medications, which were later coded into categories shown in Table 1. Antidepressants and atypical antipsychotic medications were the most frequently listed preferred medications. First-generation antipsychotic medications topped the list of medications that participants refused, nearly half of which was haloperidol. Negative side effects were the most common reason for refusing particular medications. Most individuals were willing to try medications not listed in their directive if side effects could be eliminated or their physician recommended it.

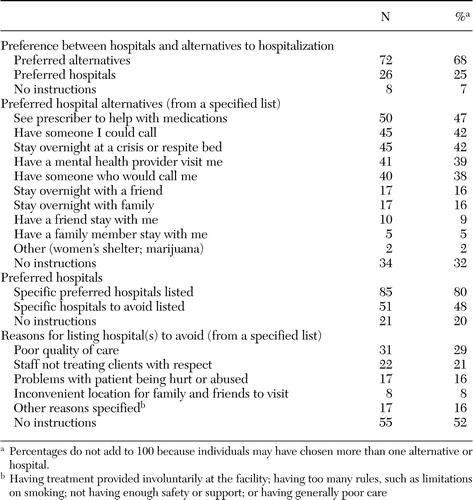

Hospitals and alternatives to hospitalization. About two-thirds of participants (68 percent) expressed a preference for hospital alternatives over hospitalization, particularly alternatives provided by professionals rather than family or friends, as shown in Table 2. Participants selected alternatives from a preestablished list. Although most participants preferred hospital alternatives, nearly all respondents recognized the need for hospitalization in some circumstances and specified at least one preferred hospital. About half specified at least one hospital to avoid, most frequently the state hospital. Participants cited poor care as the most common reason for wanting to avoid a given hospital.

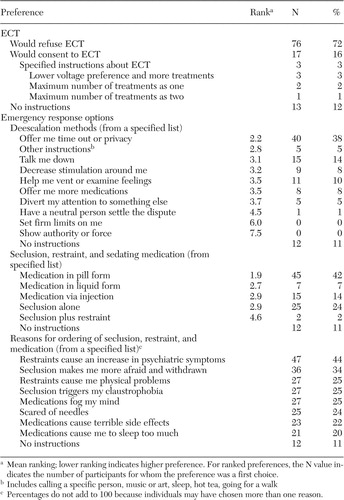

ECT. Nearly three-quarters (72 percent) indicated refusal of ECT, as shown in Table 3. Of those consenting to ECT (N=17), three selected instructions about the number and voltage of administrations.

Emergency response including seclusion, restraint, and medication. Ninety-four participants (89 percent) selected at least one method of deescalating crises from a preestablished list, and most participants wanted to have privacy or to be offered time out, as shown in Table 3.

Participants generally ranked medication, especially in pill form, as preferred over seclusion or seclusion plus restraint. Participants most frequently reported increased psychiatric symptoms, fears, and physical problems as reasons for their preferences.

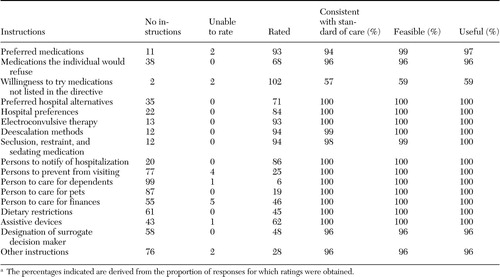

Clinical utility of treatment preferences

All treatment preferences were rated as feasible, useful, and consistent with practice standards for at least 95 percent of the directives, with the exception of instructions about willingness to use medications not listed in the directive, as shown in Table 4. This finding was because of a small number of individuals who indicated that they would reject trying such medications under any circumstances.

Nontreatment personal care instructions

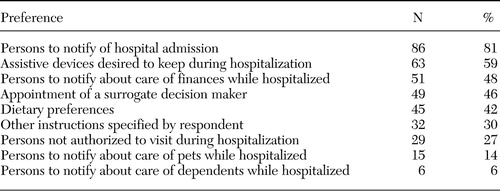

The proportion of participants who specified instructions about nontreatment personal care instructions are shown in Table 5.

People to contact and people not authorized to visit during hospitalization. Most participants (81 percent) specified individuals to be notified of hospital admissions. Parents were most frequently listed, followed by siblings, friends, clinicians, spouses, and children. Only one-quarter of participants (27 percent) specified people not authorized to visit during hospitalization, most often first-degree relatives, friends, or spouses.

Assistive devices. Slightly more than half of the participants (59 percent) selected, from a preestablished list, at least one assistive device to be retained during hospitalization. Almost all were corrective lenses or dentures or plates.

Persons to notify about care of finances, dependents, and pets. About half of the participants (48 percent) specified someone to manage finances during hospitalization. Most often case managers were listed, followed by parents, siblings, friends, and spouses. Few participants listed someone to contact to care for pets (14 percent) or dependents (6 percent).

Dietary preferences. Forty-two percent of participants selected dietary preferences from a preestablished list. The most common foods to be avoided were sugar, salt, meats, acidic foods, and fats.

Appointment of a surrogate decision maker. Just under half of the sample (46 percent) appointed a surrogate decision maker. Most often friends were listed, followed by parents, siblings, spouses, and children.

"Other" instructions. Thirty percent of participants specified additional instructions, most often treatment for medical conditions or wanting to have someone to talk to during a crisis, to be able to sleep, or to do art or other expressive activities.

Clinical utility of nontreatment personal care instructions

All nontreatment personal care preferences were rated as feasible, useful, and consistent with practice standards for at least 95 percent of the directives.

Activation and revocation of directives

About half of the participants in the study (47 percent) chose to tie directive activation to the point of legal incapacity, and nearly all others chose activation at utilization of crisis services (22 percent) or hospitalization (24 percent).

Slightly more than half the participants (57 percent) wanted their directive to be irrevocable during periods of incapacity.

Discussion

The results suggest that individuals with severe and persistent mental illnesses can clearly specify crisis treatment preferences and reasons for their preferences in psychiatric advance directives. Contrary to concerns often raised by clinicians (16), our study further shows that advance directive instructions are largely feasible, useful, and consistent with standards of care. These indicators of clinical utility suggest that the documents will be helpful to patients and clinicians to reach mutually agreed-upon treatment (11). Furthermore, at the point that interventions specified in advance directives are medically necessary, the documents may facilitate treatment consent and collaboration, expedite the provision of clinical care, and avert hospitalizations.

Study limitations

A number of study limitations should be noted. First, directives were created by using the AD-Maker (18), in which participants selected most treatment instructions from established lists. Although this structure alleviated concerns of some patients about how to specify instructions (11), it may have also optimized the documents' clinical utility. However, clinical utility ratings were also high for medication instructions and "other" instructions, for which preestablished choices were not provided. Nevertheless, an important question for future research is whether the content and clinical utility of directives created in our study can be generalized to those created from narrative type forms that are available in some states.

Clinical utility ratings were also made on the basis of typical crises rather than during actual crises, which could inflate ratings. For example, specified alternatives to hospitalization may be consistent with standards of care for most crises but not those in which an individual is acutely suicidal.

Generalizability of study findings is also limited by our selection of participants who, because of their engagement in outpatient services, may have been more likely than others to provide instructions in advance directives consistent with familiar usual care. Future research should examine the content and utility of directives created by individuals who use self-help, crisis, or hospital services but not regular outpatient care.

Implications for clinical care, service planning, and policy

Preferences stated in advance directives suggest that professionally staffed alternatives to hospitalization, crisis phone support, 24-hour prescription availability, and a variety of crisis deescalation methods are desirable services that should be made available. Furthermore, the fact that no participants indicated refusal of all psychotropic medications, yet participants indicated a clear preference for second-generation antipsychotic medications over first-generation antipsychotics, underscores the documented desirability of these newer medications (20,21).

Slightly less than half the participants appointed a surrogate decision maker, a substantially lower rate than found in previous studies (7,11,22). This finding may reflect characteristics of our sample, which had high levels of impairment and was more reliant on formal services than family support. Nonetheless, treatment facilities would be advised to develop policies and procedures for including surrogate decision makers in treatment, as well as notifying specified individuals of hospital admission and arranging for care of finances while individuals are hospitalized.

The high rate of ECT refusal could reflect stigma associated with the treatment rather than direct experience with this intervention, in contrast to, for example, instructions for deescalating crises likely based on direct experience. Truly informed consent in creating directives could be bolstered by providing information about evidence-based interventions and the contexts in which they are used—for example, ECT would be used only after unsuccessful trials of antidepressant medications. Treatment preferences in advance directives may also change over time and various crisis situations, suggesting that the documents should be reviewed and updated periodically. It should be noted, however, that individuals creating health care advance directives for end-of-life treatment decisions face the same challenges—preferences may change over time and circumstances, and these documents are additionally made with limited information and a complete absence of relevant experience. Preferences specified within psychiatric advance directives may in fact be more reliable as they are more likely to be based on past experience.

Policy implications can first be found in our result of high clinical utility of directive instructions across all content areas, which implies that state laws should not exclude certain areas as many currently do. Also, nearly half the study participants wanted directives to be revocable, even during incapacity, which is consistent with results from one survey on this topic (11). Currently, all but one state with laws about psychiatric advance directives preclude revocation during incapacity. Whether many individuals attempt to revoke advance directives while incapacitated, how this situation is dealt with clinically, and whether fewer individuals are willing to create directives if irrevocability is the only option are important empirical and policy questions.

In sum, psychiatric advance directives provide a wealth of information about patient treatment preferences, and this information is almost uniformly considered clinically useful. Our data also suggest that people with mental illnesses are increasingly well informed about evidence-based cost-efficient interventions, such as second-generation medications and alternatives to hospitalization. As such, psychiatric advance directives are not only an important means for including patients in treatment decisions and efficiently providing care matched to needs, but they may also serve as a bellwether for appropriate treatment.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health grant R01-MH58642 and the John D. and Katherine T. MacArthur Foundation. The authors thank the following individuals for their helpful review and critique of earlier versions of this paper: Paul Appelbaum, Sharon Farmer, Ron Honberg, Charles Huffine, John LaFond, John Monahan, and Richard Ries.

Dr. Srebnik, Dr. Russo, Ms. Zick, and Dr. Jaffe are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Washington in Seattle. Ms. Rutherford is affiliated with the department of sociology at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Ms. Peto is affiliated with the department of psychology at Boston College. Dr. Holtzheimer is affiliated with the Fuqua Center for Late-Life Depression at Emory University in Atlanta. Send correspondence to Dr. Srebnik at 325 Ninth Avenue, Seattle, Washington 98104 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Medication preferences among 106 outpatients in a community mental health center who completed advance directives

|

Table 2. Preferences for hospitalization and alternatives to hospitalization among 106 outpatients in a community mental health center who completed advance directives

|

Table 3. Preferences about electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and emergency response options among 106 outpatients in a community mental health center who completed advance directives

|

Table 4. Clinical utility of instructions in psychiatric advance directives of 106 outpatients in a community mental health centera

a The percentages indicated are derived from the proportion of responses for which ratings were obtained.

|

Table 5. Preferences for nontreatment personal care among 106 outpatients in a community mental health center who completed advance directives

1. Hoge S: The Patient Self-Determination Act and psychiatric care. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 22:577–586, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

2. Srebnik D, LaFond J: Advance directives for mental health treatment. Psychiatric Services 50:919–925, 1999Link, Google Scholar

3. Swanson J, Tepper M, Backlar P, et al: Psychiatric advance directives: An alternative to coercive treatment? Psychiatry 63:160–172, 2000Google Scholar

4. Winick B: Advance directive instruments for those with mental illness. University of Miami Law Review 51:57–95, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

5. Frese F: Advocacy, recovery, and the challenges of consumerism for schizophrenia. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 21:233–249, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Srebnik D: Benefits of Psychiatric Advance Directives: Can We Realize Their Potential? Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice: in pressGoogle Scholar

7. Backlar P, McFarland, B, Bentson H, et al: Consumer, provider, and informal caregiver opinions on psychiatric advance directives. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 28:427–441, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Geller J: The use of advance directives by persons with serious mental illness for psychiatric treatment. Psychiatric Quarterly 71:1–13, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. LaFond J Srebnik D: The impact of mental health advance directives on patient perceptions of coercion in civil commitment and treatment decisions. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 25:537–555, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Sutherby K, Szmukler G: Crisis cards and self-help crisis initiatives. Psychiatric Bulletin 22:4–7, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Swanson J, Swartz M, Hannon M, et al: Psychiatric advance directives: A survey of persons with schizophrenia, family members, and treatment providers. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health 2:73–86, 2003Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Backlar P, McFarland B: A survey on use of advance directives for mental health treatment in Oregon. Psychiatric Services 47:1389–1389, 1996Google Scholar

13. Miller R: Advance directives for psychiatric treatment: A view from the trenches. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 4:728–745, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Rosenson M, Kasten A: Another view of autonomy: Arranging for consent in advance. Schizophrenia Bulletin 17:1–7, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Fleischner R: Advance Directives for Mental Health Care: An analysis of State Statutes, Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 4:788–804, 1998Google Scholar

16. Srebnik D, Brodoff L: Implementation of mental health advance directives: Service provider issues and answers. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 30:253–268, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Sherman P: Computer-assisted creation of psychiatric advance directives. Community Mental Health Journal 34:351–362, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Swanson J, Swartz M: Psychiatric advance directives: Considerations and questions for research. Presented at the MacArthur Initiative on Mandated Community Treatment, Concord, Massachusetts, Oct 2001Google Scholar

19. Endicott J, Spitzer R, Fleiss J, et al: The Global Assessment Scale: A procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry 33:766–771, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Menzin J, Boulanger L, Friedman M, et al: Treatment adherence associated with conventional and atypical antipsychotics in a large state Medicaid program. Psychiatric Services 54:719–723, 2003Link, Google Scholar

21. Mojtabai R, Lavelle J, Gibson PJ, et al: Atypical antipsychotics in first admission schizophrenia: Medication continuation and outcomes. Schizophrenia Bulletin 9:519–530, 2003Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Backlar P, McFarland B: Oregon's advance directive for mental health treatment: Implications for policy. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 25:609–618, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar