Association Between Community and Client Characteristics and Subjective Measures of the Quality of Housing

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The objective of this study was to examine the relationship between subjective perceptions of the quality of housing among mental health consumers and both client characteristics and objective measures of the client's neighborhood. METHODS: A cross-sectional survey of a random sample of 468 male clients who were recruited from three mental health centers in Connecticut was used to assess client characteristics, including sociodemographic and clinical status, and measures of subjective quality of housing that reflected perception of both the client's residence and the neighborhood. Data describing the objective characteristics of the 233 census-tract block-group neighborhoods in which clients lived were obtained from the 2000 decennial census, from which three measures were created by using principal components analysis: average household income, affordability, and availability of plumbing and cooking facilities. Ordinary-least-squares regression analyses were used to identify client and neighborhood correlates of subjective quality of housing. RESULTS: Neither psychiatric diagnosis nor substance abuse were found to be significantly associated with any of the subjective housing quality measures. Clients who were living in their own place with others, those who were less bothered by side effects of medications, and those who were living in higher-income neighborhoods were more satisfied with the overall quality of their housing. CONCLUSIONS: Client assessments of subjective quality of housing, both overall and along specific subdimensions, are largely independent of commonly used diagnostic and symptom measures of mental health status. Consumers' subjective experience of housing quality are significantly associated with objective measures of neighborhood characteristics, particularly the mean household income of the neighborhood.

Housing supports have been increasingly recognized as an important element of community life for persons with serious mental illness (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13). A national survey of members of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI) found that housing assistance and support was among the most valued, but least available, type of service for persons with mental illness (14). Although access to housing assistance or services was ranked as the third most important of 11 types of services examined, behind only medication and hospitalization, fewer than one-third (31 percent) of NAMI members' relatives with serious mental illness had received such services.

The problem of poor-quality housing among people with serious mental illness was also documented in a study that compared indicators of housing and neighborhood quality between independently housed adults with serious mental illness and the general population. Although the groups differed little on housing affordability and crowding indicators, people with serious mental illness reported a greater number of physical problems with their housing, such as cracked or broken windows, and a greater number of neighborhood problems, such as crime, compared with the general population (15). However, a subsequent study found that neighborhood quality among formerly homeless users of Section 8 housing certificates with mental illness was at least as high as, if not higher than, that among Section 8 users without a mental illness (16).

Although neither of these studies examined client or community correlates of the quality of housing in detail, two studies have attempted to identify such predictors. A study of users of Section 8 housing certificates with serious mental illness found that subjectively perceived housing problems were associated with reduced housing stability and unmet mental health service needs (15). A study of a sample of consumers of public mental health services that relied on case managers' assessments showed that case managers of black men and women and of white men reported a lower quality of housing than case managers of white women (17). However, these studies examined only a limited number of client and neighborhood characteristics.

Housing quality may be measured objectively, on the basis of ratings by trained interviewers of housing unit and neighborhood characteristics; this is the approach used by the U.S. Bureau of the Census in administering the biannual American Housing Survey (18). Alternatively, housing quality may be evaluated subjectively by asking consumers about their level of satisfaction with various aspects of their living environments. For example, in the Lehman Quality of Life Interview (QOLI), consumers are asked to indicate "how they feel about" various aspects of their residence and aspects of the surrounding neighborhood on a 7-point scale ranging from "terrible" to "delighted" (19).

Although consumers' perception is paramount in measuring subjective quality of housing, we know little about the extent to which consumers' perceptions of housing quality are affected by either their own sociodemographic and clinical characteristics or objective characteristics of the housing units and neighborhoods in which they live. For example, age, depression, and discomfort with side effects of medication could color clients' perceptions of housing quality. If so, researchers, clinicians, and policy makers who are interested in including subjective housing quality outcomes (housing satisfaction) may need to consider such factors when evaluating the effectiveness of various housing interventions or when formulating community-based housing policies for persons with serious mental illness.

In this study we sought to identify client and objective neighborhood characteristics significantly associated both with a unidimensional measure of overall subjective quality of housing and with subscale measures representing specific dimensions of subjective quality of housing.

Methods

The Connecticut Outcomes Study

The Connecticut Outcomes Study (COS) was designed to compare patient characteristics, clinical status, and treatment process at three mental health service providers in Connecticut. The study was based on face-to-face interviews with a random sample of 533 male outpatients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder, or other psychosis from three sites: the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Connecticut Healthcare System (196 patients, or 37 percent) and two state-operated mental health centers—one affiliated with a university (190 patients, or 36 percent) and the other with no academic affiliation (147 patients, or 28 percent). Patients were excluded if they were undergoing inpatient treatment or were female (because there would have been too few female patients in the VA sample to allow adequate comparisons). Interviews were administered during the period 1996 to 1997. Patients gave written informed consent and were paid $20 for their time. Institutional review board approval was obtained at the authors' parent institution and at each of the three mental health facilities.

Study participants

The study sample consisted of all domiciled male participants in the COS (468 participants, or 88 percent). Participants who were homeless, including those who lived mostly in a single-occupancy hotel or boarding home, or who were institutionalized for most of the 60 days before the interview date were excluded, because the focus of the study was housing quality.

Measures

Client characteristics. Client characteristics included sociodemographic characteristics (age, race, marital status, education, employment, and income), living arrangement, community adjustment, and clinical status (mental and physical health). Clients' responses to two items asking the number of nights spent during the previous 60 days in various living arrangements and the presence of others in the home were crossed to create a five-level categorical living arrangement variable: alone, in own place with family, in own place with non-kin, in someone else's place, and in a halfway house.

Clinical status items included psychiatric diagnoses, symptoms, medication, lifetime psychiatric hospitalization, substance abuse, and physical health. Primary psychiatric diagnoses were abstracted from clients' charts. The intensity of psychiatric symptoms was rated by trained interviewers using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (20). Subjective distress was measured with 33 items from the SCL-90 (21). Use of alcohol and illicit drugs was assessed by using composite indexes from the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (22). Clients rated their physical health on a 5-point scale (19) and identified the total number of physical health problems from a list of 13 conditions, with responses including 0, no problem, 1, had problem but received no treatment, and 2, had problem and received treatment. Thus the medical problems scale ranged from 0 to 26 points.

Adjustment to community living was measured by the size of social support networks and by lifetime incarceration. Clients were asked how many people they felt close to in each of nine relationship categories—for example, parents, siblings, friends, and health care providers. A continuous social support variable was computed by summing the number of persons in each of these nine relationship categories, indicating the total number of persons to whom the client felt close.

Neighborhood characteristics. Population and housing characteristics of the 233 census-tract block-group neighborhoods in which clients resided at the time of the interview were downloaded from the Census 2000 Web site (www.census.gov). On the basis of these data, ten neighborhood variables were obtained: median household income, percentage of persons with incomes above the poverty level, home ownership rate, median gross rent (contract rent plus cost of utilities), percentage of one-bedroom rental units with a gross monthly rent of at least $500, percentage of rental units with gross rent below 20 percent of household income, percentage of household income spent on gross rent, and percentage of housing units with complete plumbing facilities, kitchen facilities, and both plumbing and kitchen facilities.

A factor analysis of these ten variables (varimax rotation) produced a three-component solution in which nine of ten factors had loading scores of at least .75. These three components were composed by neighborhood income (four of the ten variables), plumbing and kitchen facilities (three variables), and affordability (two variables). Standardized scores for the items in each of these factors were averaged for use in multivariate regression analyses.

Subjective housing quality. An overall measure of subjective housing quality was constructed by using all 24 housing quality items and six subscales representing four housing quality dimensions (space and privacy, physical maintenance, affordability, and relationship with landlord) and two neighborhood quality dimensions (safety and cleanliness, and convenience). These measures were derived from two housing quality scales—one documenting the extent to which various types of problems were present in the residence and neighborhood (12 items, ranging from 0, no problem, to 2, a big problem) (23) and another indicating the presence of various positive housing and neighborhood attributes (16 dichotomous items coded as 1, not present, or 2, present) (18). A more detailed description of the six measures of subjective housing quality is available from the authors on request.

Analyses

First we evaluated independence of the overall and six dimension-specific housing quality measures by using intercorrelation analysis. Next, bivariate analyses were used to identify client characteristics to be included in multivariate analyses of housing quality. A common set of all demographic and clinical characteristics that were significantly associated bivariately with at least two housing quality measures were used as independent variables in all multivariate models.

Finally, multivariate ordinary-least-squares regression models were used to identify client and community predictors of both the overall measure and six dimension-specific measures of subjective housing quality. The same 14 predictors (seven sociodemographic, four clinical, and three neighborhood characteristics) were used in all seven multivariate regression models. Demographic factors were entered first as a block, followed by clinical characteristics and then objective neighborhood characteristics and site dummy variables. All analyses were adjusted for clustered sampling within the three facilities by using the regression procedure with the cluster parameter of Stata 6.0 statistical software (24).

Results

Bivariate associations

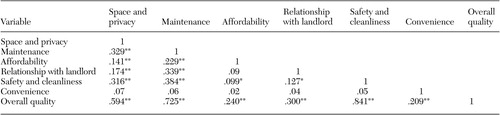

Bivariate associations among the six measures of housing quality were generally low, ranging from .02 to .38 (Table 1), showing that these measures assess different aspects of subjectively perceived quality of housing.

Predictors of housing quality

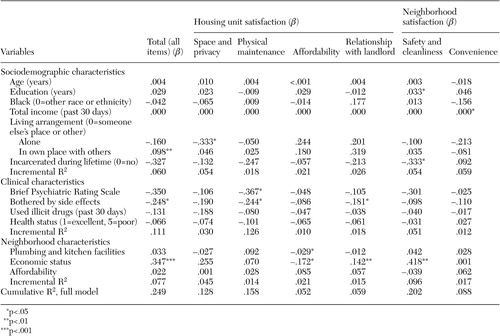

On bivariate analysis, 14 characteristics—seven sociodemographic characteristics, four clinical characteristics, and three community characteristics—were significantly associated with at least two measures of subjective quality of housing. These 14 characteristics are shown in Table 2. Contrary to our expectation, none of the following clinical characteristics was associated with multiple measures of subjective housing quality: psychiatric diagnosis, severity of alcohol or drug use problems, and number of chronic health problems. These variables were accordingly excluded from further analysis.

In multivariate analyses relatively few client sociodemographic or clinical measures were significantly associated with subjective quality of housing. Most important, clients who were living in their own place with others, those who were less bothered by side effects of medications, and those who were living in higher-income neighborhoods were more satisfied with the overall quality of their housing (Table 2).

Turning to the six subscales, perhaps paradoxically, clients who lived alone were less satisfied with the space and privacy in their homes than others. One possible explanation for this is that clients who were living alone had smaller apartments because of the higher cost of living alone, and these smaller living spaces may have impinged on their sense of privacy—for example, living in a small efficiency apartment rather than living in a house with family members.

More symptomatic clients and those who were more bothered by side effects of medication were less satisfied with the physical maintenance, or state of repair, of their homes than other clients.

Clients who were living in neighborhoods with homes that had less complete plumbing and kitchen facilities and those who were living in lower-income neighborhoods were more satisfied with the affordability of their homes, presumably because the rent was lower.

Those who were bothered by side effects of medication were less satisfied with their relationship with their landlord, whereas those who were living in higher-income neighborhoods were more satisfied with their landlord.

Clients who lived in higher-income neighborhoods were also more satisfied with the safety and cleanliness in their neighborhoods, as were clients who had more years of formal education. In contrast, clients who had been incarcerated during their lifetime were less satisfied with safety and cleanliness.

Finally, clients with higher total incomes were more satisfied with the convenience of living in their neighborhood (Table 2).

Discussion

Our major finding was that overall subjective quality of housing comprises six independent subdimensions with generally weak bivariate associations ranging from .05 to .38. Moreover, multivariate results showed that distinctly different sets of sociodemographic, clinical, and neighborhood characteristics predicted the overall housing quality measure and the six subscales. The independence of the six subjective housing quality measures suggests the need to use multidimensional measures of subjective quality of housing, in contrast to more conventional use of single aggregate measures.

The most significant and consistent predictors of subjective quality of housing in our analyses were distress caused by side effects of medication and living in higher-income neighborhoods. Clinicians and policy makers who are seeking to enhance subjective quality of life among clients with serious mental illness may seek to address troublesome side effects, and, most important, expand the supply of subsidized housing in higher-income neighborhoods.

It is notable that most sociodemographic characteristics (age, race or ethnicity, income, lifetime incarceration rate, and living alone independently) were associated with either no measure or only one measure of subjective quality of housing. Likewise, most clinical characteristics showed little to no association with subjective quality of housing (psychiatric distress, illicit drug use, and general health status). These nonsignificant findings suggest that clients' assessments of subjective quality of housing are largely independent of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics identified in previous studies as predictors of overall housing satisfaction (15,17). We believe this difference in findings from previous studies reflects an important advance given that this is the first study to examine the relationship between both a broad range of client sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and measures of objective neighborhood characteristics and multiple dimensions of subjective quality of housing in a representative sample of outpatients with serious mental illness.

It is also notable that this is the first study to successfully use objective measures of housing quality based on census data in the evaluation of housing status among people with serious mental illness. Such measures may be of use in other studies.

Our cross-sectional research design precluded conclusions of causality, but it seems far more likely that objective factors would be responsible for subjective satisfaction rather than the reverse. In addition, the exclusion of women from the sample limits the generalizability of these findings to male consumers of outpatient mental health services. These findings may also not be generalized to inpatients and others who are not receiving routine outpatient mental health care. Finally, data were not available on the length of time clients resided in the housing setting rated at the time of the interview. Ideally, an analysis of housing environments such as this would take into account the longitudinal patterns of housing experienced by the respondents.

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that client assessments of subjective quality of housing, both overall and among specific dimensions of the quality of the housing unit and the quality of the neighborhood, are made largely independent of commonly used diagnostic and symptomatic measures of mental health status. Objective measures of neighborhood characteristics, especially mean household income, are significant predictors of consumers' subjective experiences.

The authors are affiliated with the Northeast Program Evaluation Center (NEPEC) of the Department of Veterans Affairs in West Haven, Connecticut, and with the department of psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven. Send correspondence to Dr. Mares at NEPEC/182, 950 Campbell Avenue, West Haven, Connecticut 06516 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Intercorrelations among specific dimensions and overall subjective quality of housing among 468 outpatients with serious mental illness

|

Table 2. Predictors of standardized scores on subscale and overall measures of subjective quality of housing among 468 outpatients with serious mental illness

1. Baker F, Douglas C: Housing environments and community adjustment of severely mentally ill persons. Community Mental Health Journal 26:497–505, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Carling PJ: Major mental illness, housing, and supports: the promise of community integration. American Psychologist 45:969–975, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Livingston JA, Srebnik D: States' strategies for promoting supported housing for persons with psychiatric disabilities. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:1116–1119, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Hogan MF, Carling PJ: Normal housing: a key element of a supported housing approach for people with psychiatric disabilities. Community Mental Health Journal 28:215–226, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Livingston JA, Srebnik D, King DA, et al: Approaches to providing housing and flexible supports for people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 16:27–43, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Carling PJ: Housing and supports for persons with mental illness: emerging approaches to research and practice. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:439–449, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Knisley MB, Fleming M: Implementing supported housing in state and local mental health systems. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:456–461, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Newman S, Ridgely MS: Independent housing for persons with chronic mental illness. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 21:199–215, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Srebnik D, Livingston J, Gordon L, et al: Housing choice and community success for individuals with serious and persistent mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal 31:139–152, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Carling PJ: Emerging approaches to housing and support for people with psychiatric disabilities, in Handbook of Mental Health Economics and Health Policy, vol 1: Schizophrenia. Edited by Moscarelli M, Rupp A, Sartorius N. New York, Wiley, 1996Google Scholar

11. Lehman AF, Newman SJ: Housing, in Integrated Mental Health Services: Modern Community Psychiatry. Edited by Breakey WR. London, Oxford University Press, 1996Google Scholar

12. Parkinson S, Nelson G, Horgan S: From housing to homes: a review of the literature on housing approaches for psychiatric consumer/survivors. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health 18:145–164, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Wong YI, Solomon PL: Community integration of persons with psychiatric disabilities in supportive independent housing: a conceptual model and methodological considerations. Mental Health Services Research 4:13–28, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Hatfield AB, Gearon JS, Coursey RD: Family members' ratings of the use and value of mental health services: results of a national NAMI survey. Psychiatric Services 47:825–831, 1996Link, Google Scholar

15. Newman SJ: The housing and neighborhood conditions of persons with severe mental illness. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:338–343, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

16. Newman SJ, Reschovsky JD: Neighborhood locations of Section 8 housing certificate users with and without mental illness. Psychiatric Services 47:392–397, 1996Link, Google Scholar

17. Uehara ES: Race, gender, and housing inequality: an exploration of the correlates of low-quality housing among clients diagnosed with severe and persistent mental illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 35:309–321, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. US Bureau of the Census: Codebook for the American Housing Survey Data Base:1973 to 1993. Cambridge, Mass, Abt Associates, 1990Google Scholar

19. Lehman AF: A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning 11:51–52, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports 10:799–812, 1962Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Derogatis LR: Symptoms Checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R) Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual, 3rd ed. Minneapolis, National Computer Systems, 1994Google Scholar

22. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, O'Brien CP, et al: An improved diagnostic instrument for substance abuse patients: the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 168:26–33, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Newman SJ: The accuracy of reports on housing and neighborhood conditions by persons with severe mental illness. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 18:129–136, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Stata Corporation: Intercooled Stata 6.0 for Windows 98/95/NT. College Station, Tex, 1999Google Scholar