The Clinical Strategies Implementation Scale to Measure Implementation of Treatment in Mental Health Services

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors describe the development of the Clinical Strategies Implementation Scale (CSI), an instrument designed to help providers measure the extent to which evidence-based strategies have been implemented in the treatment of persons with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. METHODS: Nine ordinal scales were devised to measure key aspects of treatment strategies that have been associated with clinical and social recovery from schizophrenia: goal- and problem-oriented assessment, medication strategies, assertive case management, mental health education, caregiver-based problem solving, living skills training, psychological strategies for residual problems, crisis prevention and intervention, and booster sessions. A study of interrater reliability was conducted with 15 trained raters from participating centers in Athens, Auckland, Bonn, Budapest, Gothenburg, and Tokyo who assessed 54 cases. Each treatment strategy was weighted according to its effect size in clinical trials. Correlation analyses were conducted to explore associations between the total CSI score and ratings of clinical, social, and caregiver outcomes each year over four years of continued treatment of 51 patients. RESULTS: Interrater reliability ranged from .93 to .99. Four annual total CSI ratings were significantly correlated with impairment, disability, functioning, work activity, and an index of recovery. Most correlations were stronger in years 3 and 4 than in years 1 and 2. CONCLUSIONS: Reliable and valid assessment of the implementation of evidence-based strategies in clinical practice is feasible. The quality of integrated program implementation may be associated with improved clinical and social recovery from schizophrenic disorders.

The benefits of evidence-based treatment can be replicated in routine practice when the application of such treatments approximates that provided in clinical trials (1). A major criticism of the evidence-based approach is that controlled trials are poor models for clinical practice, because practitioners follow the protocols rigidly and the flexibility necessary for optimal treatment is lacking (2,3). Although such criticism is well founded in the case of fixed-dosage trials of medication or psychosocial strategies, adherence to clearly defined manuals to ensure that treatment is implemented in an optimal way is a basic principle of health science. Substantial deviations from the tried and tested can be justified only when they are evaluated in an experimental manner and shown to be superior. Single-case designs provide a means for such experimentation in routine practice, and individualized assessment of benefits can facilitate early recognition of success or failure of carefully chosen strategies. This practical approach provides guidance to adjust dosages or to change to alternative strategies and is likely to improve treatment effectiveness and efficiency, potentially beyond that of clinical trials.

The Optimal Treatment Project (OTP) began in 1995 as an international collaborative attempt to assess long-term recovery from schizophrenic disorders when patients receive the combination of evidence-based biomedical and psychosocial treatments that have shown major benefits in controlled trials (4). This pragmatic trial focused on continued training and review of teams to ensure that the manual-based program was implemented in the optimal way (5,6).

The program included pharmacotherapy with adherence and side effects management, assertive case management, education of patients and caregivers about schizophrenia and its treatment, caregiver-based problem solving, living skills training in real-life settings, early detection of exacerbations with intensive home-based crisis management, and specific psychological strategies for treating persisting psychotic, nonpsychotic, and deficit symptoms, as well as for substance abuse or aggressive behavior. These strategies included core evidence-based treatments for schizophrenia spectrum disorders (7,8,9,10,11,12) as well as several that have been validated in clinical trials in nonpsychotic populations (13). The single-case approach that was used to select and sequence the strategies was based on an assessment of patients' current personal life goals and key problems and on comprehensive psychiatric assessment (14.

Clinical decision making involved not only the multidisciplinary treatment team but also the patients and key family members or friends whom the patients chose to support them throughout the program. To ensure consistency and informed decision making, all assessment and treatment strategies and reviews were conducted with the aid of identical guidebooks for professionals, patients, and caregivers (15,16).

Methods to ensure that this wide range of treatment strategies was implemented in the most effective and efficient manner are not simple. This article outlines the development, reliability, and predictive validity of a preliminary set of scales to support this process. The scales were designed for use in two ways: for continuing individual case review and supervision by the clinical team, patients, and their caregivers and for annual external audits of treatment implementation to explore teams' strengths and weaknesses in the application of specific strategies to a random selection of their cases and to clarify further training needs. In addition, we were interested in examining whether implementation of the treatment strategies improved over time and contributed to clinical and social recovery.

Methods

Developing the Comprehensive Strategies Implementation Scale

First it was necessary to define criteria for optimal application of each treatment strategy as well as criteria for potentially unsafe applications. Various degrees of suboptimal application may have fewer benefits without proving harmful. However, some interventions may be considered harmful, such as excessive doses of medications that produce unwanted side effects or education that implies that parents are to blame for the mental disorders of their children. After thorough study of treatment manuals and the clinical research literature, an initial consensus was reached among the OTP's multidisciplinary teams on a series of scales that defined optimal, suboptimal, and harmful criteria and that were based on ratings ranging from -1, potentially harmful, to 4, optimal. Two examples of the scales may clarify the rating approach.

For the caregiver-based problem-solving scale, a rating of -1 indicates that confrontational interventions are used with patients and caregivers; a rating of 0 indicates that no such interventions are provided and that key caregivers are not involved in clinical management plans. A rating of 1 indicates that sessions are provided for some skills that patients and caregivers lack but that the interventions are didactic and do not involve practice or coaching. A rating of 2 indicates that skill-training sessions are provided for most skills needed to enhance the stress management capacity of patients and caregivers but that the skills are used only when participants are prompted by a clinician. A rating of 3 indicates clear evidence that all problem-solving and interpersonal communication skills are acquired but that they are applied without prompting only in training session practice. A rating of 4 indicates clear evidence that skills are used in real life and in household meetings held at least once every two weeks.

For the medication management strategies scale, a rating of -1 indicates the unnecessary use of additional medications or dosages outside the recommended range. A rating of 0 indicates that no specific medication strategies are used when they are clearly indicated. A rating of 1 indicates that the choice of medication is based on the patient's current symptom profile. A rating of 2 indicates evidence of continued assertive management of adherence and side effects. A rating of 3 indicates that the targeted dosage has been achieved, that the patient and caregiver participate in medication management, that the patient reports benefits and unwanted effects and early warning signs, and that the benefits, effects, and signs are all monitored continuously. A rating of 4 indicates that plasma levels are measured or that other standardized procedures are used to determine that a minimally effective dosage is achieved and that nonresponse to the medication is reviewed and the problem solved effectively.

It can be seen that the ratings 1 and 2 reflect standard practice. However, in the OTP it as been our aim to provide "optimal" practice by adding all evidence-based refinements to the program. For example, we do not consider that we have achieved our treatment goals if patients and caregivers have merely acquired skills of stress management to the level that they can use them in treatment sessions when prompted to do so by the therapist. To have any lasting value skills training must ensure that patients and caregivers use these specific skills in their everyday lives. Similarly, patients benefit from continuing medication only if OTP therapists ensure that they adhere to the treatment program outside the hospital or day hospital and suffer minimal addition stresses from side effects or inconvenience in their everyday lives. For this reason, therapists continue to conduct collaborative problem solving with patients and their key caregivers until there is clear evidence that the evidence-based biomedical and psychosocial strategies have been implemented competently in real-life settings. All these "optimal" strategies have been associated with improved outcomes and are clearly outlined in the treatment manuals that are provided for all professionals, patients, and caregivers (15,16).

Some strategies are core treatments in most cases, whereas others are necessary for an individual's specific residual symptoms and life problems. The core strategies include assertive case management, neuroleptic medication, education, caregiver-based problem solving, and crisis prevention and management. Additional strategies include specific cognitive-behavioral strategies for residual symptoms or problems and living skills training, such as supported employment and social skills training. Last but not least, continued comprehensive biomedical and psychosocial assessment and review are included to help target the strategies to the phase of the disorder and the current needs of patients and caregivers.

Each scale was weighted according to its estimated overall therapeutic potency in the recovery process. After studying the literature on the efficacy of the strategies, including meta-analyses and comparative effect sizes, an international focus group of 12 experienced clinicians reached a consensus on the weightings. Weightings ranged from ×1 for assessment, education, living skills, and specific psychological strategies; ×2 for assertive case management, crisis management, and booster sessions; and ×4 for care-based problem solving, ranging to ×6 for optimal medication. The sum of the weighted scores on each of the nine items that were considered relevant to each patient's treatment program at each review point was expressed as a percentage of the maximum score possible on those items. This calculation gave an estimate of the quality of implementation of the current treatment plan and its therapeutic potential at regular intervals in a readily understood way—"the percentage of 'optimal' treatment implemented for each case," or the "CSI index."

As noted, the complex decision of which strategies are relevant for individuals at different phases of recovery was made in conjoint reviews between all team professionals, patients, and caregivers. The annual external audit provided an opportunity to discuss the selection of strategies for individual cases with an expert, particularly those in which progress was limited.

Training

Training was conducted by the first author in the context of annual external audits of treatment implementation in centers in Australia, Canada, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, and Sweden. Each training course lasted a total of four to six hours. Trainees were all experienced providers of the treatment methods. After they had studied the CSI manual, each of the ratings was discussed, examples were given, and misunderstandings were clarified. Small groups then practiced rating ten cases. Divergent ratings were discussed, and a consensus was reached.

An international study of interrater reliability

Fifteen trained raters participated in the reliability study. They included seven men and eight women—three psychiatrists, seven psychologists, one nurse, three social workers, and one occupational therapist. Two or more raters from six centers (Athens, Auckland, Bonn, Budapest, Gothenburg, and Tokyo) co-rated the CSI scales for 54 patients who had DSM-IV schizophrenic disorders and who had received at least six months of treatment. Ratings were conducted in case reviews with the key clinician. When further information about treatment was needed, it was provided by other clinicians involved with that case, by chart review, and, occasionally, by patients and caregivers. The manual-based assessment and treatment methods facilitated this review process.

The interrater agreement on each scale and the overall weighted score of optimal treatment implemented—the CSI index—was measured.

Predictive validity

We examined the correlation between the CSI index and clinical and social outcomes. This analysis was conducted for 51 patients who were consecutively admitted to one site, the Kessariani Community Mental Health Centre in Athens, where none of the patients dropped out or had missing data over four years (1997 to 2001) of continued treatment (in other sites only a small random sample was reviewed annually).

The CSI index for individual cases at one, two, three, and four years was correlated with ratings at each of these assessment points of symptom severity, as measured by the Mental Functions Impairment Scale; disability, as measured by the Disability Index; the Global Assessment of Functioning; work activity, as measured by the total time spent in weekly work activities; and caregiver stress, as measured by the Carer Stress instrument. These ratings were made by independent reliable raters (an intraclass correlation coefficient greater than .80). The CSI was also correlated with an index of "recovery" at the four time points (none, no improvement on impairment or disability; partial, substantial improvement on impairment or disability but residual problems remain; or full, no evidence of impairment or disability). The outcome measures are described in more detail elsewhere (17,18).

Pearson's correlation coefficient was used whenever data were distributed normally.

Results

Reliability

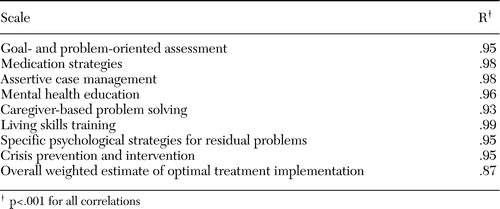

As shown in Table 1, interrater agreement on eight CSI scales ranged from .93 to .99. The ninth scale that measured booster sessions had too few cases to be included. The interrater agreement on the weighted CSI index was .87.

Predictive validity

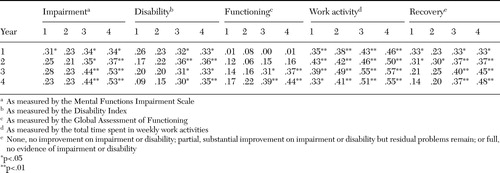

Correlations between the CSI index for each of 51 patients and their annual outcome assessments over four years are summarized in Table 2. The CSI at 36 and 48 months correlated significantly with all patient outcome measures. However, at 12 and 24 months the associations were weaker. Only work activity correlated strongly with the CSI at each assessment point. No significant correlations with caregiver stress were found at any point.

A repeated-measures analysis of variance showed a linear improvement of treatment implementation in the Athens service over the four years of monitoring (F=15.1, df=3, 150, p<.001). The mean CSI index scores rose from 58.7±16.1 percent in the first year of the program to 66.0±15.8 percent in the second year, 69.7±19.0 percent in the third year, and 70.3±18.6 percent in the fourth year. Post hoc analyses indicated that in years 2, 3, and 4 patients were receiving significantly more optimal treatment than in the first year of the program (p<.001).

Discussion

This study provides preliminary support for the hypothesis that the implementation of an evidence-based treatment program for schizophrenia can be measured reliably and that the CSI may be a useful tool for monitoring strategies associated with good clinical and social outcomes. Clinical review of treatment plans and progress is well established in most mental health teams. However, there is a tendency to focus on the number and type of interventions provided and the subjective experiences of service providers and users rather than on criteria indicating the effective implementation of assessment and treatment strategies that appear to contribute to optimal outcome in clinical research (10). The Clinical Strategies Implementation scales are an initial attempt to quantify the core strategies used in the treatment of schizophrenia spectrum disorders and to weight them according to their potency in facilitating clinical and social recovery. The results suggest that we have been modestly successful in achieving this goal, at least when the ratings were applied to individual cases by assessors who were independent and blind to outcome measures and in teams that were well trained in a comprehensive manual-based program.

It remains to be seen whether these scales have similar utility when applied in regular peer reviews by other clinical teams that use somewhat different programs. Our observations suggest that case reviews using the CSI provide constructive feedback to clinicians on treatment progress and problems that has been generally well received after the usual fear of negative evaluation has been overcome. The annual reviews are conducted in a supportive team meeting in the form of case supervision, in which the review and discussion of each case lasts about an hour. When clear deficits in implementation skills are detected, remediation is provided either during the discussion or in a continued training workshop usually arranged during the external reviewer's visit.

The lack of strong associations between treatment implementation and benefits in the first two years of treatment and caregiver stress may be partly explained by the fact that the Athens service that conducted this substudy had already been applying these strategies in a less systematic way for several years before the start of the evaluation project. However, even though therapists in this service were experienced with the evidence-based methods, significant improvements were measured over the four-year period, which suggests that the CSI reviews may have contributed to treatment improvement.

To date, the CSI has been used mainly to monitor the effectiveness of implementing optimal treatment strategies in individual cases and to help pinpoint areas in which treatment was not delivered according to the manuals and guidebooks provided. This approach enabled further training and supervision of members of the teams treating these cases, which may account for the stronger associations with outcome in the latter years. We have hypothesized that a 50 percent overall rating will provide good maintenance of benefits and prevent deterioration and that a rating of 80 percent or more will provide maximum benefits. To some extent this clinical hypothesis has been validated by the data from Athens. Patients who showed no tendency toward recovery after four years of treatment had a mean CSI rating of 59 percent at the four-year assessment, whereas those who were free of significant symptoms or disability had a mean CSI rating of 79 percent, with the intermediate group averaging 67 percent. This suggestion that there may be a threshold of implementation associated with trends toward recovery may also help explain the stronger correlations between the CSI index and outcome measures that were found as time progressed. These results suggest that our preliminary efforts may be on the right track, even if much work is needed to refine them.

An added strength of this initial attempt to measure treatment implementation is its international application. Centers in 12 countries participated, and many more were involved in the earlier development phases. No notable cultural differences in treatment implementation have been observed. The Athens center was able to provide complete data, and at other centers random sampling of cases reviewed annually limited the sample size for correlations between the CSI index and outcome measures. Further cross-validation is under way in Sweden, and results will be reported.

The CSI fosters a flexible treatment approach based on the personal life goals and associated problems of patients and caregivers, which change at various phases of recovery. This flexible focus on the quality of life of all service users in a program that aims to help them achieve their personal goals, rather than merely establish disease control and relapse prevention, is consistent with recent recommendations for comprehensive treatment (14,19,20). The focus is on enabling patients and caregivers to apply treatment strategies in their real lives without the direct supervision of professionals. However, it is recognized that for a few patients a lack of personal resources may necessitate more direct prompting to ensure optimal implementation (14,21). Prompting may take the form of home visits to ensure medication adherence or telephone contacts to facilitate the application of specific psychosocial strategies. Use of the CSI enables teams to detect these needs at an early stage and to make plans to maximize the effectiveness of treatment strategies.

In addition to assessing the implementation and adherence of the professional team to optimal practice through external audits, it is important to conduct regular reviews of progress with the patient and key caregivers. This session-by-session review of progress on personal goals and problems has been a core component of the Optimal Treatment Project; however, it has not been formally assessed in controlled trials, although it is a vital component of clinical treatment (22). Some researchers have suggested that some of the therapeutic benefits observed in clinical research may be attributed merely to the use of structured assessment strategies (23).

This study represents preliminary work in progress and has several limitations. The assessment of predictive validity was conducted in only one center. All the centers included in the reliability study were committed to using the manual-based strategies considered optimal for this project, and it cannot be assumed that the associations would have been robust if they were examined at centers that used less structured or alternative evidence-based methods. On the other hand, the consistently high fidelity of treatment implementation in most cases reduced the variance for the correlation analyses. Further research is in progress to consolidate these findings.

A second limitation is the disease-specific nature of the scales and their weightings. Clearly the same treatment strategies would not be valid for nonpsychotic disorders. The scales of assessment, medication, education, assertive case management, crisis management, and life skills training strategies could all be applied to most mental disorders without substantial modification, but their relative weightings would differ. For example, whereas pharmacotherapy is a cornerstone in the long-term treatment of most cases of schizophrenia and affective psychosis, it has a less substantial role in anxiety disorders, for which psychological strategies are more potent. However, it is relatively simple to develop a set of weightings for different disorders through careful review of the efficacy literature. More problematic are cases in which patients have comorbid disorders and more than one major syndrome needs effective treatment. Such cases often present a clinical management dilemma, and it is possible that the CSI approach may help resolve some of the confusion that often reduces the efficacy of evidence-based strategies in cases of schizoaffective or bipolar disorders, as well as those in which mixed anxiety and depressive symptoms coexist. Controlled research on complex cases is sparse, so that clear guidelines on the choice and prioritization of clinical strategies are limited.

A major problem that has been highlighted is the potential to confound process and outcome. We have argued that optimal treatment implementation does not finish as soon as the manual-based approach is applied according to the basic protocol. Instead, therapists must ensure that training and clinical problem solving continue until there is clear evidence that strategies are being implemented in the real lives of patients and their caregivers. In recent years several specific strategies have been developed to enhance adhesion to pharmacologic and psychosocial treatments. In the approach taken in this study, such procedures are integrated into the basic treatment strategies and are therefore considered part of the process of treatment.

Of course, implementation of treatment strategies and their success in enhancing clinical and social outcomes will always be a collaborative process between therapists and patients. For this reason, implementation of treatment strategies will depend to a greater or lesser degree on interactions between patients and therapists. Factors such as therapist-patient relationships, patient motivation, life stresses, supportive relationships, and levels of cognitive impairment may place limitations on the rate at which treatment strategies may be implemented in an optimal way. When ratings of client-specific implementation are made with the CSI, the "difficulty" of patients is taken into account; however, it is not considered a reason for not continuing to seek ways to achieve optimal application of strategies that have proven efficacy. The CSI encourages teams to persist with "slow learners," even if it may take a considerable time to achieve optimal implementation and improved clinical and social outcomes. The close association between patients' treatment adherence and clinical benefits is a potential confounder of this method, at least for cognitive-behavioral and skill development strategies in which patient and caregiver implementation in the natural environment is considered to be an integral part of treatment. However, the outcome measures that we describe in this article are those related to reduced clinical and social morbidity, not merely the acquisition and application of skills.

A final difficulty is the need to continually update treatment strategies and their relative potency. Recent examples include advances in medication, psychological strategies for residual psychotic symptoms, and social strategies for employment (24,25,26). The current version of the CSI is the tenth (CSI-1.10), but it gives only limited importance to these recently established psychosocial strategies. It gives them the same weightings as health education or skills training and lower weightings than case management or crisis management; for several such strategies, conclusive evidence of benefits for schizophrenia spectrum disorders has yet to be provided (27,28). Our system of weighting was based on a detailed review of controlled treatment trials in the mid-1990s, and it may not be consistent with more recent innovations. However, it has been our collective experience that if the core strategies are implemented effectively over an extended period, fewer patients are likely to require more complex interventions.

The outcomes achieved by the international Optimal Treatment Project at 24 months suggest strongly that implementation of evidence-based strategies in this manner may contribute to clinical and social recovery from schizophrenia (18,29). It may be concluded that some of the benefits may be attributable to use of the CSI to enhance the quality of treatment implementation in individual cases. It is hoped that similar pragmatic studies that are currently planned may refine this methodology, which at this stage seems promising but rather primitive (30).

Acknowledgments

The other members of the Optimal Treatment Program Collaborative Group are Ken Burnett, M.Sc., Ballarat, Australia; Carla Belotti, M.D., Como, Italy; Massimo Casacchia, M.D., L'Aquila, Italy; Scott Clark, M.D., Sydney, Australia; Naomi Cowan, B.Sc., Auckland, New Zealand; Dave Erickson, Ph.D., Vancouver, Canada; Robyn Gedye, M.Sc., Auckland, New Zealand; Rolf Grawe, Ph.D., Trondheim, Norway; Judit Harangozo, M.D., Budapest, Hungary; Bert Hager, M.Sc., Bonn, Germany; Tilo Held, M.D., Berlin, Germany; Barry Hunter, Tamworth, Australia; Bo Ivarsson, M.D., Boras, Sweden; Antonino Mastroeni, M.D., Como, Italy; Isabel Montero, M.D., Valencia, Spain; Tommy Norden, M.D., Lysekil, Sweden; Joan Obiols, M.D., Andorra; Alexandra Palli, M.Sc., Athens, Greece; Esterina Pellegrini, Como, Italy; John Pullman, M.Sc., Ballarat, Australia; Rita Roncone, M.D., L'Aquila, Italy; Kei Sakuma, M.D., Koriyama, Japan; Mehmet Sungur, M.D., Istanbul, Turkey; Zsolt Unoka, Budapest, Hungary; Atilla Varga, M.D., and Zsusa Varga, M.D., Szekesfehervar, Hungary; Franco Veltro, M.D., Campobasso, Italy; and Joseph Ventura, Ph.D., Los Angeles.

Dr. Falloon is affiliated with the department of psychiatry at Auckland University in New Zealand and with the Optimal Treatment Project Collaborative Group, 06050 Mercatello, Perugia, Italy (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Economou and Ms. Palli are with the department of psychiatry at the University of Athens in Greece. Dr. Malm is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Gothenberg in Sweden. Dr. Mizuno is with the department of psychiatry at Keio University in Tokyo. Dr. Murakami is with the department of social psychiatry at Meijiukin University in Tokyo.

|

Table 1. Pearsons correlation coefficients for agreement among 15 raters who rated 54 patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia on eight scales from the Clinical Strategies Implementation Scale

|

Table 2. Correlations between total scores on the Clinical Strategies Implementation Scale and measures of impairment, disability, functioning, work activity, and recovery at year 1, 2, 3, and 4 assessments of treatment of 51 patients with schizophrenia

1. Drake RE, Goldman HH: The future of evidence-based practices in mental health care. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 26:1011–1016,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Essock SM, Goldman HH, Van Tosh L, et al: Evidence-based practices: setting the context and responding to concerns. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 26:919–938,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Essock SM, Drake RE, Frank RG, et al: Randomized controlled trials in evidence-based mental health care: getting the right answer to the right question. Schizophrenia Bulletin 29:115–123,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Falloon IRH, and the Optimal Treatment Project collaborators: Optimal treatment for psychosis in an international multisite demonstration project. Psychiatric Services 50:615–618,1999Link, Google Scholar

5. Gilbody S, Wahlbeck K, Adams C: Randomized controlled trials in schizophrenia: a critical perspective on the literature. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 105:243–251,2003Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Hotopf M, Churchill R, Lewis G: Pragmatic randomised controlled trials in psychiatry. British Journal of Psychiatry 175:217–223,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. American Psychiatric Association: Practice guideline for treatment of patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 154(suppl 4):1–63,1997Google Scholar

8. Bustillo J, Lauriello J, Horan W, et al: The psychosocial treatment of schizophrenia: an update. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:163–175,2001Link, Google Scholar

9. Kane JM, McGlashan TH: Treatment of schizophrenia. Lancet 346:820–825,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) client survey. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:11–20,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Lehman AF, Buchanan RW, Dickerson FB, et al: Evidence-based treatment for schizophrenia. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 26:939–954,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Clinical Guideline 1: Schizophrenia. Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Schizophrenia in Primary and Secondary Care. London, National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2002Google Scholar

13. Chambless DL, Baker M, Baucom DH, et al: Update on empirically validated therapies: II. the clinical psychologist 51:3–16, 1998Google Scholar

14. Kopelowicz A, Liberman RP: Integrating treatment with rehabilitation for persons with major mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services 54:1491–1498,2003Link, Google Scholar

15. Falloon IRH, and the Optimal Treatment Project collaborators: Integrated Mental Health Care: A Guidebook for Consumers. Perugia, Italy, Optimal Treatment Project, 1997Google Scholar

16. Falloon IRH, Graham-Hole V, Fadden G, et al: Integrated Mental Health Care: A Programme of Training in Clinical Management of Mental Disorders Using Effective, Efficient Intervention Strategies Within a Multidisciplinary Team. Ariete, Perugia, Italy, Optimal Treatment Project, 1996Google Scholar

17. Falloon IRH, and the Optimal Treatment Project collaborators: Mental Health Assessment Toolkit: Interviews and Rating Scales. Ariete, Perugia, Italy, Optimal Treatment Project, 2001Google Scholar

18. Falloon IRH, Montero I, Sungur M, et al: Implementation of evidence-based treatment for schizophrenic disorders: two-year outcome of an international field trial of optimal treatment. World Psychiatry 3:104–109,2004Medline, Google Scholar

19. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, rev ed. American Journal of Psychiatry 161(suppl):1–56,2004Google Scholar

20. Resnick SG, Rosenheck RA, Lehman AF: An exploratory analysis of correlates of recovery. Psychiatric Services 55:540–547,2004Link, Google Scholar

21. Liberman RP, Glynn S, Blair KE, et al: In vivo amplified skills training: promoting generalization of independent living skills for clients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry 65:137–155,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Gilbody SM, House AO, Sheldon TA: Outcome measures and needs assessment tools for schizophrenia and related disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1):CD003081, 2003Google Scholar

23. Carroll RS, Miller A, Ross B, et al: Research as an impetus to improved treatment. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:377–380,1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Miller AL, Chiles JA, Chiles JK, et al: The Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) schizophrenia algorithms. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:649–657,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Pilling S, Bebbington P, Kuipers E, et al: Psychological treatments in schizophrenia: I. meta-analysis of family intervention and cognitive behaviour therapy. Psychological Medicine 32:763–782,2002Medline, Google Scholar

26. Bond GR, Drake RE, Mueser KT, et al: An update on supported employment for people with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 48:335–346,1997Link, Google Scholar

27. Pilling S, Bebbington P, Kuipers E, et al: Psychological treatments in schizophrenia: II. meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials of social skills training and cognitive remediation. Psychological Medicine 32:783–791,2002Medline, Google Scholar

28. Fiander M, Burns T, McHugo GJ, et al: Assertive community treatment across the Atlantic: comparison of model fidelity in the UK and USA. British Journal of Psychiatry 182:248–254,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Malm U, Ivarsson B, Allebeck P, et al: Integrated care in schizophrenia: a 2-year randomized controlled study of two community-based treatment programs. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 107:415–423,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Mueser KT, Torrey WC, Lynde D, et al: Implementing evidence-based practices for people with severe mental illness. Behavior Modification 27:387–411,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar