Community Tenure of People With Serious Mental Illness in Assertive Community Treatment in Canada

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study followed consumers after admission to an assertive community treatment program to determine when the first hospital admission was more likely to occur, which variables predicted community tenure, and, more specifically, whether the availability of within-program hospital beds predicted community tenure. METHODS: Data were gathered from three assertive community treatment programs in southeastern Ontario—the psychosocial rehabilitation program, the community integration program, and the assertive community treatment team program. Only the psychosocial rehabilitation program provided within-program beds. Hospital records of consumers who entered a program between July 1, 1990, and December 1, 1999, were examined prospectively until January 1, 2000, in order to record time to the first admission. Survival analysis based on the life-tables method was used to estimate the probability of remaining out of the hospital at 90-day intervals. Factors associated with time to admission were identified by using the Cox proportional hazards model. RESULTS: A total of 333 consumers were followed: 117 consumers in the psychosocial rehabilitation program, 105 in the community integration program, and 111 in the assertive community treatment team program. Findings indicated that consumers were most likely to be admitted to a hospital in the nine months after entering an assertive community treatment program. A diagnosis of substance use disorder, higher past hospital use, and the availability of within-program beds were associated with an increased risk of admission. CONCLUSIONS: Studies have shown that hospitalization remains a reality for many consumers and therefore warrants further study. The survival model proved advantageous by allowing a more complete and comparable description of consumers' hospitalization patterns that cannot be achieved with previously used methods, and it offered the power of regression analysis.

Assertive community treatment is a community treatment model that was originally developed by Stein and Test (1) as an alternative to hospitalization. A primary goal of this model is to prevent hospitalization. The model's premise is that consumers have better outcomes if they are supported directly in their community environments. The Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care in Ontario, Canada, has identified assertive community treatment as an appropriate treatment model for consumers with serious mental illness, particularly those who are heavy users of inpatient services (2), and the ministry has invested in evaluating the outcomes of the dissemination of the model (Krupa T, Eastabrook SJ, Gerber G, unpublished data, 1997).

Several studies of assertive community treatment have demonstrated that the model is effective in reducing hospitalizations (3). Investigators have demonstrated a reduction in the hospitalization of consumers in assertive community treatment by using different follow-up times. One study may compare the number of admissions in the six-month period before the consumer starts assertive community treatment with the six-month period after entry to the program, and another study may use one-year periods (4,5). Studies that use different time frames when reporting changes in admission rates are very difficult to compare (6). In addition, this method does not consider censored cases—that is, data available from consumers who do not experience a hospitalization. Therefore, rather than using a statistical method that relies on counting events that may be infrequent, such as hospitalization, this study examined community tenure—more specifically, the time frames in which hospital admissions were most likely to occur—by using a survival model.

A second issue is that, in the context of dissemination, there have been variations in the implementation of the assertive community treatment model. These variations have raised concerns about their possible differential effects on desired outcomes (7,8,9). One clearly identifiable variation in a local assertive community treatment program is the availability of within-program hospital beds. Although this variation is meant to enhance continuity of care, its impact on the model's goal of community tenure is unknown.

This paper reports on a longitudinal observational study that contributes to the knowledge base of assertive community treatment by investigating the following research questions: Within what periods are admissions more likely to occur? And what variables predict community tenure; more specifically, does the availability of within-program beds predict community tenure?

Methods

Research design

This study examined existing data from hospital records by using a retrospective longitudinal observational design. To maximize the usefulness of this design, a survival model was used to increase comparability among future studies, to allow for censored cases, and to control for observed differences among programs in the absence of random assignment. The dependent variable for the survival model was community tenure, or time to hospital admission.

This study was part of a larger four-year prospective study designed to examine the relationship between key elements of assertive community treatment teams and various outcomes and to examine consumers' experience of the services provided (Krupa T, Eastabrook SJ, Gerber G, unpublished data, 1997). The study presented here is a small substudy that explored community tenure by using a survival model and the influence of within-program beds as a variation of the assertive community treatment model.

Participants

Participants were adults who entered one of the three assertive community treatment programs in southeastern Ontario from July 1, 1990, to December 1, 1999. Participants were followed prospectively to January 1, 2000, in order to record any hospital admissions. In accordance with the provincial guidelines for receipt of assertive community treatment services, participants had been given a diagnosis of a significantly serious and persistent mental illness that resulted in impaired functioning in activities of daily living and had continuous high service needs (2). The research ethics board of Queen's University approved this study.

Setting

The components identified by Stein and Test (1) are the basis for the guidelines that are currently used in the development of assertive community treatment programs in Ontario (2). These guidelines describe services that target adults with severe and persistent mental illness; are driven by consumer needs; are provided to consumers directly; are ongoing and unlimited in duration; have staff with small, fixed caseloads; are provided in the consumer's own environment; and are provided 24 hours per day by a multidisciplinary team. All three programs studied followed these guidelines to a certain extent with key variations among them.

The three assertive community treatment programs—the psychosocial rehabilitation program, the community integration program, and the assertive community treatment team program—were governed by two provincial psychiatric hospitals in Ontario. In October 1998 the degree of variation of the three assertive community treatment programs from the original Stein and Test model (1) was assessed with the Index of Fidelity of Assertive Community Treatment (IFACT) (9). Possible scores on the index range from 0 to 14, with higher scores indicating greater program fidelity to the original model. A lack of dedicated staff positions for vocational and substance use specialists and higher caseload numbers lowered the IFACT scores across all three programs. A summary of each program follows.

The psychosocial rehabilitation program was established in 1993. The program was associated with a 20-bed inpatient unit where its office was located. A distinguishing feature of this program and the one primarily accountable for the IFACT score of 12.5 was the availability of six hospital beds for consumers who lived in the community and might require hospitalization.

Created in 1991, the community integration program was governed by the same provincial psychiatric hospital, but its office was located off-site. Consumers who required admission to the hospital were usually admitted through the psychiatric hospital's acute admission unit. The IFACT score for this program was 11.

The assertive community treatment team program was established in 1990 by a second provincial psychiatric hospital. The program office was located in a separate building at the psychiatric hospital. At the time of data collection, caseload numbers for the service were affected by service restructuring and rural service demands. The IFACT score for this program was 10.5.

Measures

Demographic and hospitalization data were obtained from the clinical records departments of the provincial psychiatric hospitals. Demographic data comprised age, sex, education level, marital status, and primary diagnosis. Primary diagnoses were broadly categorized as schizophrenia psychosis, affective psychosis, personality disorder, substance use disorder, or organic brain disorder. Although only the primary diagnosis was considered for this study, participants often had several diagnoses. This finding may explain the presence of persons in this sample with diagnoses that are not generally considered to be the target of assertive community treatment. Hospitalization history was recorded as the number of days in a hospital and the number of admissions to a hospital in the three years before program entry (indirect measures of severity of illness). Program-related variables were the age of the assertive community treatment program at program entry and whether or not there were within-program beds available. Time to admission was defined as the number of days elapsed from entry into assertive community treatment until the first psychiatric hospitalization.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS Advanced Models 10.0 (10). Significance for all procedures was determined at the .05 probability level (two-tailed test).

The characteristics of the participants from three assertive community treatment programs were compared by using analysis of variance or chi square analysis when appropriate. Survival analysis that was based on the life-tables method was used to estimate the probability of remaining out of a hospital at 90-day intervals (11). A modified Weibull curve was computed for the survival function (12,13). Survival curves were compared by using the Wilcoxon test, which yields a test statistic that is distributed as a chi square value when the null hypothesis of equivalent survival experience is true.

Last, the Cox proportional hazards model, a regression model for analyzing survival data, was used to describe the relationship of selected consumer and program variables to time to admission after adjustment for appropriate covariates (11). Forward stepwise selection of variables was used. The criterion for entry into the model was p<.05, and for removal it was p>.10. All variables were assessed to determine whether they met the proportional hazards assumption. None of the variables significantly violated this assumption.

Results

Characteristics of the sample

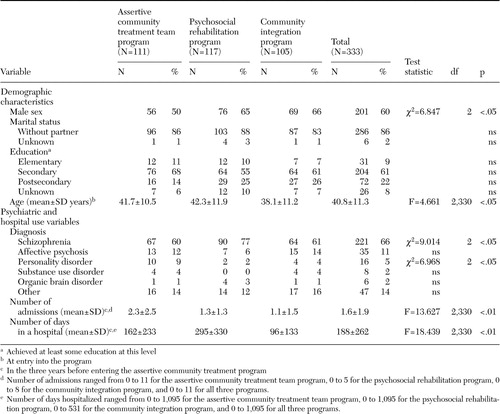

A total of 333 consumers were followed: 117 consumers in the psychosocial rehabilitation program, 105 in the community integration program, and 111 in the assertive community treatment team program. The characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. Where statistically significant overall differences were found among the participants of the assertive community treatment programs, breakdown analyses were computed to determine the source of the differences; these differences were statistically controlled for in the Cox regression analysis.

Compared with the assertive community treatment team program, the psychosocial rehabilitation program and the community integration program had a greater proportion of males. Most participants in the groups were middle aged, although participants in the community integration program were younger than participants in the other two programs. Most participants did not have a partner, and more than half of them had received at least some secondary education. More than 60 percent of the participants had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and differences in the distribution of diagnoses existed among the programs. The average participant had less than two hospital admissions to a hospital and had spent about six months in a hospital in the three years before entering an assertive community treatment program. In these three years, participants of the assertive community treatment team program were admitted to a hospital more frequently than participants of the other two programs. Compared with participants in the assertive community treatment team program and the community integration program, those in the psychosocial rehabilitation program spent a greater number of days in a hospital during the three years before entering a program.

Admission to a hospital

A total of 185 participants (56 percent) experienced a hospitalization before the end of the observation period, and 148 (44 percent) were censored (that is, admission had not occurred by the end of the study period). The participants were monitored for an admission from one month to nine years (mean±SD=4.2±2.7 years).

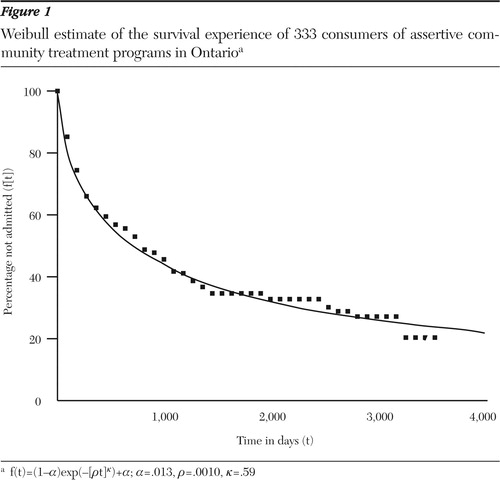

The modified Weibull estimate of the overall survival for the 333 participants of the three assertive community treatment programs is shown in Figure 1, in which the asymptote parameter α reflects the proportion who would never be admitted and the rate parameter ρ, as modulated by κ, reflects the rate of admission.

The median length of community tenure for this sample was 784 days. The survival curve shows a rapid drop in the cumulative survival probability during the first three intervals (270 days), indicating that the greatest likelihood of admission to a hospital occurred in these nine months. Following this drop, the proportion who had not been hospitalized begins to level off at about 25 percent.

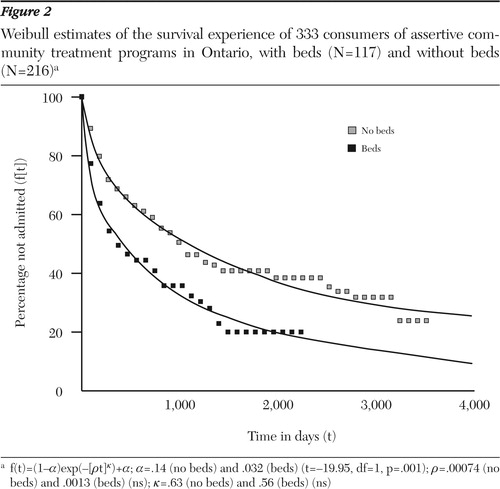

Comparison of the three programs revealed a statistically significant difference in length of community tenure between the program with beds and each of the two programs without beds available. Therefore, the three assertive community treatment programs were reconfigured into two groups—those with and those without available beds—and their survival distributions were compared. The modified Weibull estimate of survival for the assertive community treatment program with available beds and those without beds is shown in Figure 2.

Comparison of the parameters of the Weibull model indicated that in the long term the group that did not have access to within-program beds had a greater proportion of participants who had not been hospitalized (α parameter). Median length of community tenure for the participants of the assertive community treatment program with beds was 368 days, and it was 1,002 days for the assertive community treatment programs without beds. Overall, participants in a program that did not have beds available had a statistically better chance of not being hospitalized (Wilcoxon matched pairs, χ2=12.4, df=1, p<.001).

Factors predicting time to admission

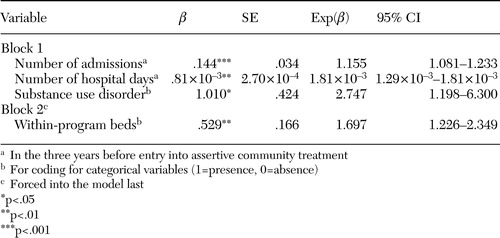

Finally, a Cox regression analysis was performed to determine the degree of association of selected consumer and program variables with time to admission. The aim of this analysis was to examine the effect of available beds while controlling for possible confounding variables—that is, participant characteristics. The statistics for the final Cox model are shown in Table 2.

Neither age at program entry nor a diagnosis of schizophrenia, affective psychosis, personality disorder, or organic brain disorder was a significant predictor of time to admission. The variables selected for the final model were the number of admissions and the number of days in a hospital in the three years before assertive community treatment, a diagnosis of substance use disorder, and the availability of within-program beds. The index exp(β) is the hazard ratio for the variable. The hazard ratio is an estimate of the effect, direct or indirect, of the variable. Therefore, the results showed a 15.5 percent increase in risk of admission for each hospital admission in the three years before entry into an assertive community treatment program. Also seen was a .1 percent increase in the risk associated with each additional day spent in a hospital in the three years before assertive community treatment. Participants with a diagnosis of substance use disorder were 2.8 times as likely as those without such a diagnosis to be admitted to a hospital. Participants in an assertive community treatment program with beds were 1.7 times as likely as those in a program without beds to be admitted to a hospital.

Discussion

Hospital admission

Although assertive community treatment programs have proven effective in decreasing hospitalization of consumers, no evaluation studies that used survival analysis to examine hospitalization of consumers in assertive community treatment programs were found in the literature. The most pertinent study is by Setze and Bond (14), which used survival analysis to evaluate a psychiatric rehabilitation program. Setze and Bond's study demonstrates a key advantage to using survival analysis: the comparability among studies. These authors showed that participants in the psychiatric rehabilitation program had a 46 percent chance of experiencing at least one hospital admission after one year in the program (14). Their finding was similar to the findings reported here: the sample of consumers of the assertive community treatment programs had a 41 percent probability of at least one hospital admission in the year after entry into an assertive community treatment program (Figure 1).

Data showed that after seven years approximately 25 percent of the consumers did not experience a hospital admission (Figure 1). However, care should be taken in interpreting the end of the survival curve (15). Nevertheless, the overall trend shows that the risk of admission decreased over time, indicating that the longer consumers were able to stay out of a hospital, the more likely they were to remain out. Therefore, consumers who do not experience an admission in the long term may be a special subgroup that warrants specific investigation. A major goal of assertive community treatment programs is to care for consumers in the community, and this study reflects progress toward achieving that goal.

Factors predicting time to admission

Differences among programs that previous research suggested might be confounding were statistically controlled for in this study through the use of Cox regression. However, statistical control cannot substitute for random assignment, which was not possible in this study. Therefore, this study provides only a preliminary understanding of factors affecting time to admission for this sample. Nevertheless, the study presented here provides valuable pointers for future studies that examine the effects of program and consumer characteristics on admission to a hospital.

The results showed that a higher number of hospital admissions in the three years before assertive community treatment was associated with an increase in risk of hospital admission. The cycle of hospital admission and readmission has been well established, and this finding was therefore expected.

Similarly, consumers in this study who had spent more time in a hospital in the period before assertive community treatment tended to be hospitalized earlier. Indeed, some consumers had been hospitalized for the entire three years before entering an assertive community treatment program. Generally, studies of assertive community treatment have not taken account of the previous number of days of hospitalization in relation to return to a hospital. Given that time in a hospital can be considered an indirect measure of severity of illness, future studies of assertive community treatment that examine the effect of hospitalization history should examine not only the previous number of hospitalizations but also the previous number of days in a hospital. Ideally, studies would include a direct measure of severity of illness, such as a psychiatric symptom rating scale. A rating scale that examines specific categories of psychiatric functioning, such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (16), may be more appropriate than global ratings of functioning, which have failed in the past to reliably predict readmission to hospital (17).

In this study substance use disorder was the only diagnostic category that predicted an increased risk of hospital admission. This finding supports that of Carpenter and colleagues (18), who found that abuse of drugs or alcohol was related to multiple hospital admissions. In the study presented here, a diagnosis of substance use disorder was included only if it was recorded as the consumer's primary diagnosis. Nevertheless, many consumers may have problems with substance abuse that are considered secondary to another diagnosis. It is therefore possible that the effect of substance use disorder was underestimated in the study presented here. Future studies may consider the effect of a secondary diagnosis of substance use disorder and include a greater number of participants with this diagnosis. Such a study would elucidate the role of substance use disorder in the hospitalization of assertive community treatment consumers. The results of the study presented here lend support to the evaluation of integrating substance abuse treatment into assertive community treatment programs.

This study showed that the availability of within-program beds continued to be a predictor of admission to a hospital after other covariates, such as consumer characteristics, were controlled for. For the programs studied here, this modification to services appeared to influence the dynamics of service delivery. Although there will be instances when admission to a hospital is preferable to treatment in the community, some investigators have speculated that hospital admission may result simply because there are hospital beds available (8,19).

Other factors that may be related to admission were not considered in this study. For example, poor medication compliance has been shown to be related to hospital admission (20,21), but these data were unavailable for this study.

Conclusions

Studies have shown that although assertive community treatment can reduce hospital admissions, hospitalization remains a reality for many consumers and therefore warrants further study. A key finding of this study is that consumers are at highest risk of admission in the nine months after entering an assertive community treatment program. This finding was elucidated by using a survival model that allowed a more complete and comparable description of consumers' hospitalization patterns that could not be achieved with previously used methods.

This study found that a diagnosis of substance use disorder, higher past hospital use, and access to within-program hospital beds put consumers at greater risk of hospital admission. Although the findings reported here cannot be generalized without the use of a randomized experimental design, the study generated both consumer and program factors that should be considered for future studies of consumers' community tenure. Again, the survival model proved advantageous for this part of the study. Cox regression embodies the power of regression analysis applied to survival data. Knowledge gained from this and future studies may help avoid unnecessary admissions and will have clear implications for the future planning and evaluation of assertive community treatment programs that target people at risk of admission at the time they are most at risk.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care in collaboration with the Ontario Mental Health Foundation, the Centre for Addictions and Mental Health, and the Canadian Mental Health Association-Ontario, the Jan Metcalf Research Award of the Registered Nurses Foundation of Ontario, and the Nursing Research Interest Group of the Registered Nurses Association of Ontario.

Ms. Joannette is affiliated with the department of research and the department of mental health services at Providence Continuing Care Centre, 508 Freeman Crescent, Kingston, Ontario, Canada K7K 7C9 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Lawson is with the department of psychiatry, Dr. Eastabrook is with the School of Nursing, and Dr. Krupa is with the School of Rehabilitation Therapy at Queen's University in Ontario. Preliminary results of this study were presented at the Canadian Conference on Nursing Research, held June 12 to 15, 2002, in Quebec City and the Canadian Psychiatric Association annual meeting, held November 15 to 19, 2001, in Montreal, Quebec.

Figure 1. Weibull estimate of the survival experience of 333 consumers of assertive community treatment programs in Ontarioa

af(t)=(1-α)exp(-[ρt]κ)+α; α=.013, ρ=.0010, κ=.59

Figure 2. Weibull estimates of the survival experience of 333 consumers of assertive community treatment programs in Ontario, with beds (N=117) and without beds (N=216)a

af(t)=(1-α)exp(-[ρt]κ)+α; α=.14 (no beds) and .032 (beds) (t=-19.95, df=1, p=.001); ρ=.00074 (no beds) and .0013 (beds) (ns); κ=.63 (no beds) and .56 (beds) (ns)

|

Table 1. Sample characteristics of 333 consumers of assertive community treatment in Ontario

|

Table 2. Summary of the final Cox regression model using forward stepwise selection of covariates predicting time to admission for three assertive community treatment programs in Ontario

1. Stein LI, Test MA: Alternative to mental hospital treatment. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:392–397,1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Mental Health Programs and Services Group: Assertive Community Treatment Guideline. Toronto, Ministry of Health of Ontario, 1997Google Scholar

3. Burns BJ, Santos AB: Assertive community treatment: an update of randomized trials. Psychiatric Services 46:669–675,1995Link, Google Scholar

4. Bond G, Witheridge T, Setze P, et al: Preventing rehospitalization of clients in a psychosocial rehabilitation program. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 36:993–995,1985Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Arana J, Hastings B, Herron E: Continuous care teams in intensive outpatient treatment of chronic mentally ill patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:503–507,1991Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Anthony W, Buell G, Sharratt S, et al: Efficacy of psychiatric rehabilitation. Psychological Bulletin 78:447–456,1972Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Lachance K, Santos A: Modifying the PACT model: preserving the critical elements. Psychiatric Services 46:601–604,1995Link, Google Scholar

8. Essock S, Kontos N: Implementing assertive community treatment teams. Psychiatric Services 46:679–683,1995Link, Google Scholar

9. McGrew J, Bond G, Dietzen L, et al: Measuring the fidelity of implementation of a mental health program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 62:670–678,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. SPSS Advanced Models 10.0. Chicago, Ill, SPSS Inc, 1999Google Scholar

11. Parmar MK, Machin D: Survival Analysis: A Practical Approach. Chichester, United Kingdom, Wiley, 1995Google Scholar

12. Lawson JS, Woogh C: Survival analysis of psychiatric readmissions and discharge data. Presented at the 44th annual meeting of the Canadian Psychiatric Association, Ottawa, Ontario, September 20–24, 1994Google Scholar

13. Cox DR, Oakes D: Analysis of Survival Data. London, Chapman and Hall, 1984Google Scholar

14. Setze P, Bond G: Psychiatric recidivism in a psychosocial rehabilitation setting: a survival analysis. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 36:521–524,1985Abstract, Google Scholar

15. Geller J, Fisher WH, Simon LJ, et al: Second-generation deinstitutionalization. II: The impact of Brewster v Dukakis on correlates of community and hospital utilization. American Journal of Psychiatry 147:988–993,1990Link, Google Scholar

16. Lukoff D, Neuchterlien K, Liberman R: Symptom monitoring in the rehabilitation of schizophrenic patients. Schizophrenia Bulletin 12:578–602,1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Klinkenberg D, Calsyn R: Predictors of receipt of aftercare and recidivism among persons with severe mental illness: a review. Psychiatric Services 47:487–496,1996Link, Google Scholar

18. Carpenter MD, Mulligan JC, Bader IA, et al: Multiple admissions to an urban psychiatric center: a comparative study. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 36:1305–1308,1985Abstract, Google Scholar

19. Nelson G, Sadeler C, Miller-Craig S: Changes in rates of hospitalization and cost savings for psychiatric consumers participating in a case management program. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 18:113–123,1995Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Green J: Frequent rehospitalization and noncompliance with treatment. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:963–966,1988Abstract, Google Scholar

21. Junginger J: Psychiatric hospitalization and community-based program attendance. Psychiatric Quarterly 61:251–259,1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar