Housing Attributes and Serious Mental Illness: Implications for Research and Practice

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: This paper critically reviews studies of the relationship between housing attributes and serious mental illness, highlights important gaps in the research, generates hypotheses to be tested, and suggests a research agenda. METHODS: Studies published between 1975 and March 2000 were identified through computerized searches, previous literature reviews, and consultation with mental health and housing researchers. Criteria for inclusion included the presentation of quantitative evidence, a systematic sample of known generalizability, and systematic analytic techniques. RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS: The 32 studies that met these criteria relied on one or more of three conceptualizations of the role of housing: housing attributes or assessments as an outcome or dependent variable; housing attributes as inputs or independent variables in a model in which the outcome pertains to a nonhousing factor, such as a mental health outcome; or housing as both an input and an outcome. Three studies found no long-term effect of improved housing adequacy on housing satisfaction above and beyond case management. Three studies found better outcomes for settings that have fewer occupants. Another study suggested that persons who live in small-scale, good-quality, noninstitutional environments are less likely to engage in disruptive behavior when a larger proportion of other tenants also have serious mental illness. The strongest finding from the literature on housing as an input and an outcome was that living in independent housing was associated with greater satisfaction with housing and neighborhood. Most of the studies had methodological weaknesses, and few addressed key hypotheses. There is a critical need for a coherent agenda built around key hypotheses and for a uniform set of measures of housing an input and an outcome.

Three-fourths of the 4.6 million people with severe and persistent mental illness now live most of their lives in the community. An as yet unmeasured number of these individuals reside in independent housing and receive no on-site service supports (1,2). Researchers have devoted substantial attention to understanding which community settings work best for which individuals and under what conditions. Most of this work continues the traditional—and important—focus on the services and treatment interventions that people with mental illness may require for community living; however, a small body of research considers the housing setting itself—the relationship between an individual's psychological well-being and the physical conditions of the dwelling unit or the quality of the neighborhood.

This paper, which draws on some of my previous work (3), provides a critical review of this smaller body of research on the housing setting. The goals of the review were to identify findings, highlight important gaps in the research, generate hypotheses to be tested, and suggest a research agenda.

Methods

The review is limited to studies that used specific measures of the attributes of housing and neighborhoods. Much of the literature generally considered to fall under the "housing" rubric was therefore excluded, because it focuses on programmatic interventions in the service or social environments of different housing settings (4,5,6). The review is also largely limited to research that describes the specific service context of the study subjects. The types of housing settings ranged from group homes to independent apartments. Including only studies that described the specific service context allowed comparison of housing settings and neighborhoods with particular features across different communities while other potentially important factors, such as functioning, were held constant. Studies of persons who were domiciled and who were previously homeless were included for the same reason: to examine whether, when other factors are held constant, homelessness is associated with different responses to features of the physical environment.

Research on the mental health-housing nexus is relatively new. Thus the criteria for inclusion of a study in this review were the minimum required to guard against spurious findings: quantitative evidence, a systematic sample of known generalizability, and analytic techniques that meet basic standards of scientific rigor—for example, the application of statistical techniques that are appropriate to the question posed. It is important to note that these criteria reduce, but by no means eliminate, idiosyncratic or artifactual findings.

Studies conducted between 1975 and March 2000 were identified through extensive searches, including computerized searches using MEDLINE and PsycINFO, an examination of previous literature reviews, and consultations with experts in mental health and in housing research. A total of 280 studies on the broad topic of housing and mental illness were identified, and of those, 32 were selected for review. Studies that met the above criteria were included even if their primary goal was not to gain an understanding of the role of housing in mental health. Although their weaknesses from the housing perspective are understandable, their inclusion made it possible to distill what could and could not be learned from them about housing and mental health and to gain insight into appropriate analytic methods.

Results

The studies reviewed here explicitly or implicitly relied on one of three conceptualizations of the role of housing. The first conceptualization sees housing attributes—size of dwelling, physical quality, and neighborhood—as an outcome or a dependent variable to be explained. An example of a study relying on this conceptualization would be one that examined whether persons with serious mental illness are more likely to live in distressed neighborhoods, net of other factors—such as income—that are usually associated with the distribution of the general population in neighborhoods of varying quality.

The second conceptualization sees housing attributes as inputs or independent variables in a model in which the outcome pertains to a nonhousing factor—for example, a person's functioning or length of hospital stay. The third approach sees housing attributes as both input and outcome—for example, the effects of the physical adequacy of the dwelling on its affordability. A study may encompass more than one conceptualization.

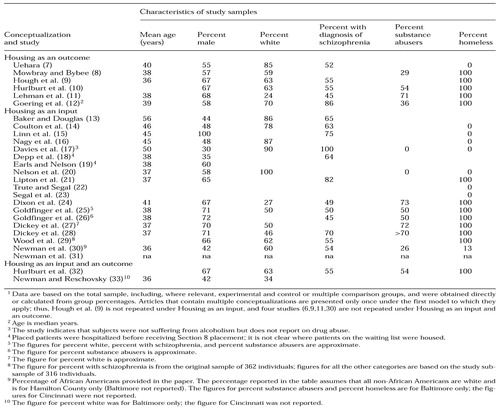

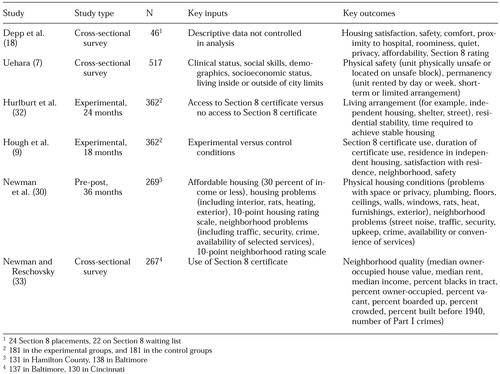

Table 1 lists the studies included in this review (7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33) by type of conceptualization and summarizes key characteristics of the study samples.

Housing as an outcome

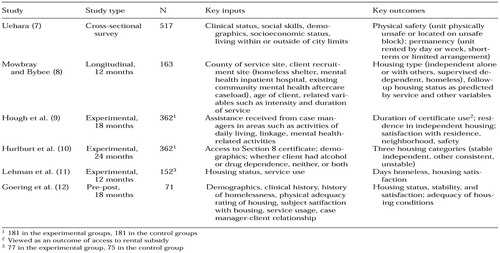

Table 2 summarizes the key design features of the six studies that examined housing as an outcome (7,8,9,10,11,12). The mean age of the individuals in the samples was the late 30s; about half of them had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The samples had more males than females (range of male subjects, 55 percent to 68 percent). The proportion of whites in the samples ranged from 24 percent to 85 percent. Substance abuse was not reported for two studies; in the other four studies it varied widely.

All of the studies except one focused on the homeless population, from individuals who were precariously housed to those who literally had no place to go at night. Observation periods ranged from a single cross-section to a follow-up period of 24 months. Two studies (11,12) examined the impact of assertive case management on housing satisfaction, which allowed the results to be compared. The other four studies addressed research questions that were unique to each, so no comparisons could be made.

In a study of outpatients of a mental health agency in King County, Washington, Uehara (7) found that race was more powerful than mental illness in predicting quality of housing and neighborhood. This finding is consistent with that reported by Newman and Reschovsky (33). However, the generalizability of the King County study is constrained by a localized sample, the reliance on cross-sectional data, the absence of any information about support networks or service use, and relatively few indicators of housing quality and community context.

The results of three studies (9,11,12) suggest that more adequate housing has no long-term effect above and beyond case management on housing satisfaction among persons with serious mental illness. In the study by Hough and colleagues (9), about 90 individuals in San Diego were randomly assigned to one of four groups. One group had access to Section 8 rent subsidies and received comprehensive case management, the second group had access to Section 8 subsidies and received traditional case management, the third group received comprehensive case management only, and the fourth group received traditional case management only. (A Section 8 rent subsidy can be used to rent physically adequate and affordable housing in the private market. The tenant's out-of-pocket rent payment is limited to no more than 30 percent of income.)

In the study by Lehman and colleagues (11), which was conducted in Baltimore, 77 individuals in the experimental group were provided with assertive community-based clinical treatment combined with intensive case management and advocacy; 75 control subjects received "services as usual." Goering and colleagues (12), using a synthetic pre-post design, interviewed a sample of participants in the Toronto Hostel Outreach Program who were provided with assertive case management with dormitory-style accommodations.

The results of these three studies are not conclusive about whether housing features affect residents' satisfaction with housing. Hough and colleagues (9) noted that the two types of case management—traditional and comprehensive—converged over time, so that after 12 months any differences in case management services were reduced or eliminated. Furthermore, their analysis focused on access to rental subsidies rather than use of subsidies. Thus two different sets of factors could have influenced the results of the study: factors that affected whether a rental subsidy was used and factors that affected the type of housing and neighborhoods that were attainable with a Section 8 certificate, such as ethnic and racial discrimination and tightness in the housing market. The information necessary to understand the effects of housing attributes—that is, whether a person used a subsidy—was not part of this study.

Lehman and colleagues (11) acknowledged two sources of contamination in their study that introduced opposing types of bias of unknown extent. First, funding for their experiment included additional housing options, which were available to individuals in both the experimental group and the control group. Most of these options were ultimately assigned to those in the experimental group; therefore, an upward bias in measuring the impacts of assertive community-based clinical treatment would be expected (24). Second, during the course of the study, the City of Baltimore funded an intervention similar to assertive community-based clinical treatment at another community mental health center. These additional services were available to individuals in the control group, so that a downward bias would be expected in measures of the impacts of such treatment.

The nonexperimental design of the study by Goering and colleagues (12) and the fact that persons who dropped out were less residentially stable than those who remained in the study call into question the generalizability of the results. The residential instability of the dropouts may explain why these results were more positive than those obtained in the experimental study by Lehman and colleagues (11). Other weaknesses of the study by Goering and colleagues included the reconstruction of preintervention status through retrospective reporting and measurement of housing satisfaction for the setting where the subject had lived the longest rather than for all settings in which the individual had lived since the last interview.

A central issue in the conceptualization of housing as an outcome is the relative importance of housing versus services for an outcome such as housing satisfaction. Therefore, the apparent lack of association between housing adequacy and housing satisfaction above and beyond case management is worthy of additional scrutiny. Ideally, the research would follow an experimental design similar to that used by Hough and colleagues (9) but with a focus on residence in decent, affordable housing and with clear distinctions between case management interventions. From a public policy perspective, the relationship between housing satisfaction, mental health outcomes, and service costs also needs to be understood. Although the quality-of-life benefits of improved housing satisfaction can be justified on humanitarian grounds, public investments based solely on improved satisfaction will remain difficult to justify unless it can be demonstrated that satisfaction is cost-effectively related to improved mental health outcomes.

Housing as an input

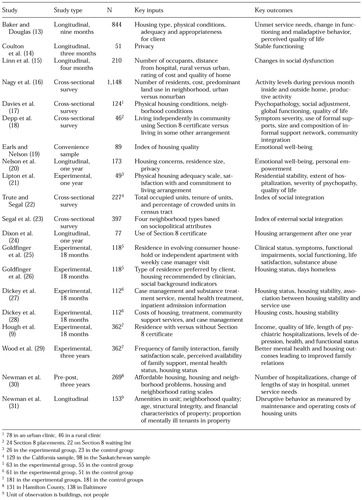

The group of studies based on the conceptualization of housing as an input is by far the largest. Table 3 summarizes the key design features of the 20 studies in this group (9,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31). The characteristics of the samples vary widely, with the exception of mean ages, which ranged from 36 to 56 years but were concentrated in the late 30s. In most of these studies, the subjects were more likely to be male and white and to have a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia. Depending on the definition of homelessness, seven to 11 of the studies focused on individuals who were homeless and mentally ill. Seven studies reported rates of substance abuse, which generally exceeded 50 percent. Study designs and duration ranged from a single cross-section to an experimental study with a 36-month follow-up.

Many studies in the housing-as-input group examined the same questions, which provided a basis for comparing their results. The topic that generated the largest concentration of research—five studies—was the effect on mental health outcomes of access to or use of a Section 8 housing certificate, either by itself or in combination with a mental health service intervention (9,18,24,29,30). Four studies examined the effects of neighborhood features on mental health outcomes (16,22,23,30). Three looked at urban versus rural location (15,16,17), three focused on the number of residents in the dwelling (15,16,20), and three examined the effects of dwelling quality (13,21,30).

The core question of the housing-as-input conceptualization is whether the housing setting has therapeutic benefits that operate independently of the type, array, and intensity of services provided. The two studies that addressed this question most directly produced different results. Baker and Douglas (13) analyzed data from a random sample of 844 clients in community support services programs in New York State (excluding New York City). The subjects were stratified by time in the program, but they were not randomly assigned to housing. Most of the data were obtained from questionnaires completed by case managers at baseline and at nine-month follow-up.

The authors found that clients who had a mental illness and also were living in physically inadequate housing were more likely to manifest maladaptive behavior, regardless of the amount of support services they received. Physical inadequacy was measured by a 5-point rating scale of neighborhood, residence exterior, residence interior, and client's personal property. Living in adequate housing was associated with an increase in residents' functioning over the nine-month study period. This finding is inconsistent with that of Hough and colleagues (9), in which access to adequate housing was not associated with a housing outcome—housing satisfaction.

Hough and colleagues (9) also found that access to rental subsidies was not significantly associated with clinical outcomes, including level of depression, time spent in a mental health setting during the 60 days before each interview, or self-reported functioning (34). However, obtaining independent housing—with or without a rent subsidy—was associated with significantly lower levels of depression and less time spent in a mental health setting in the previous 60 days. The physical adequacy of this housing—the housing indicator in Baker and Douglas (13)—was not reported.

The design used to test the question of the net benefits of the housing setting was much stronger in the study by Hough and colleagues than in the Baker and Douglas study, because the subjects were randomly selected for both the housing intervention and the case management intervention. Unlike Baker and Douglas, Hough and colleagues found no significant relationship between access to adequate housing and clinical outcomes of persons with serious mental illness above and beyond case management services. Although actual attainment of independent housing was associated with better mental health outcomes, selection bias may weaken the generalizability of this result, because the randomization was based on Section 8 access, not use.

Again, both studies have weaknesses from the specific perspective of understanding the role of housing features in mental health outcomes, separate from other influences. The Baker and Douglas study was not a randomized trial, so it is not possible to determine whether the results were attributable to housing. The authors also relied primarily on simple correlational analyses. Most important, nearly two-fifths of the individuals in the nine-month follow-up sample who were described as having "markedly deteriorated" were excluded from the analysis. The results of the study would undoubtedly have been weaker had the entire sample been included.

Beyond the issue of not distinguishing access to rental subsidies from their actual use, Hough and colleagues also relied solely on correlational analysis, making it unclear whether improved clinical status facilitated independent living or whether independent living, along with case management, improved clinical status. The finding of an association between attainment of independent housing and better clinical outcomes must be confirmed by reanalyzing the data with a different statistical modeling approach. If the association is confirmed, further testing with a similar design but implemented in different housing markets and avoiding contamination of the case management interventions would be warranted.

Findings converge in the three studies that examined the effects of number of occupants in a housing setting on mental health outcomes such as social functioning and well-being. Linn and colleagues (15), Nagy and colleagues (16), and Nelson and colleagues (20) reported that individuals with mental illness do better in settings that have fewer occupants.

After setting size and other factors are controlled for, tenant mix also appears to play a role. Tenants who lived in settings that had a larger proportion of other tenants with mental illness had better clinical outcomes (31). This result might appear to contradict the model of housing that seeks to normalize housing for individuals with mental illness because such housing leads to better outcomes. However, in the study in question (31), the sample of dwellings was limited to housing that provided small-scale, good-quality, noninstitutional environments in a community setting, with off-site services available to assist with independent living. Findings on neighborhood attributes and serious mental illness suggest that diverse, somewhat disorganized neighborhoods have salutary effects on persons with mental illness, because these types of neighborhoods are likely to be more welcoming (22,23,30). If confirmed, this finding could be useful for developing housing policies, including the targeting of subsidies to certain neighborhoods.

Housing as an input and an outcome

Table 4 summarizes the key features of the six studies that examined housing as an input and an outcome (7,9,18,30,32,33). Because most of these studies include analyses of the other two conceptualizations of the role of housing or neighborhood, they have already been discussed and therefore receive briefer mention here. Sample members were typically in their late 30s. In two of the studies the samples were composed entirely of individuals who were homeless and mentally ill (9,32). In most of the studies males outnumbered females, with the proportion of male subjects ranging from 35 percent to 67 percent.

The majority of subjects—from 52 percent to 64 percent—had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. In four of the six study samples (7,9,30,32) whites were in the majority—from 60 percent to 85 percent; in the other two studies (18,33) blacks constituted the largest group. Substance abuse data were reported in only two studies (30,32).

The strongest finding from the studies that examined housing as an input and an outcome is that living in independent housing is associated with greater satisfaction with housing and neighborhood (9). Confirmation of this finding is warranted. These positive associations between a housing feature—independent housing—and housing outcomes—satisfaction with housing and neighborhood—contrast with the insignificant associations found in the same study between comprehensive case management or traditional case management and all quality-of-life domains. As noted above, individuals in the study by Hough and colleagues (9) were not randomly assigned independent housing status; rather, they were randomly assigned to groups that did or did not have access to independent housing though Section 8 subsidies. Furthermore, the two case management interventions were not very different from one another, especially after the first year.

Conclusions

The majority of the 32 studies reviewed here suffer from one or more methodological weaknesses. In addition, a number of the analyses were not grounded in a conceptual framework that provided a clear set of hypotheses to be tested. Furthermore, most of the studies relied on correlational analysis, which cannot establish causation, that is, what affects what. Even if a positive correlation is the result of causality, correlation cannot determine direction or magnitude. The generalizability of even the randomized experiments is in doubt, because of such factors as difficulty in implementing the intervention as specified, attrition bias, and inappropriate or unknown sample definition. Problems with the analyses can be overcome by reanalyzing the data in a different way. However, it is not possible to correct for contamination introduced by the way in which an experiment is implemented.

Over and above these methodological weaknesses, no set of theories appears to be guiding this work, nor is there consistency in the methods or measures used. It is not much of an exaggeration to say that, with few exceptions, each study appears to be starting over.

As a result, much remains unknown. This body of research has not demonstrated which housing attributes or factors are critical to a mentally ill person's capacity to live independently, it has not described the types of residential alternatives that are most effective for persons with serious mental illness, it has not identified specific housing attributes that can be systematically associated with the best type of residential settings, and it has not produced any agreement on the most appropriate way to conceptualize and measure the effectiveness of the housing setting.

Deinstitutionalization is in its fourth decade, and a focus on homelessness is in its third. It is fair to ask why a systematic body of knowledge about housing and mental illness has not yet been compiled. In their landmark article on the effects of deinstitutionalization, Braun and colleagues (35) offered three possibilities. First, many mental health professionals have strong views about what is and is not effective. These views may affect the design of a study, the way in which it is conducted, and the documentation of the research and therefore the reliability of the results.

Second, virtually every aspect of research in the area of housing for people with mental illness is inherently complex, from observing and measuring an individual's psychiatric status to ensuring that the intervention being tested is what it purports to be. Finally, carrying out experimental studies in this area in ethically appropriate ways is a formidable challenge. Goldman and Morrissey (36) offer an additional explanation: much mental health policy and practice have not considered housing as a potentially key component of a system of mental health care.

Part of the problem can be attributed to the field of housing research, which does not yet have a strong theoretical base or accepted measures for future work. Moreover, the work that has been done typically applies to cross-sections of the general population rather than to persons with serious mental illness.

To ensure that the research mistakes of the past 25 years are not repeated in the next 25 years, several issues must be addressed. First, there is a critical need for a coherent research agenda built around key hypotheses of housing and mental illness. This agenda should be organized and implemented in a linear way, so that initial studies build theory and develop valid and reliable measures and later studies apply these theories and measures to test behavioral and structural relationships. Although much of the agenda will require newly designed studies, there are some opportunities for reanalyzing existing data sets with more sophisticated statistical methods that account for such problems as selectivity and attrition bias.

Future research would also be aided substantially by the establishment of a basic set of measures of housing as an input and an outcome, akin to the minimum data set on long-term care that was developed 20 years ago (37,38). The resulting agenda and research should be disseminated to as broad an audience as possible. The establishment of a National Academy of Sciences panel to study housing and mental illness would be one way of raising awareness of the issues.

Another concern is the significant methodological challenge of designing studies that address the two key policy questions: the relative effects on mental health outcomes of housing and services and of different housing-and-service bundles. Although randomized experiments are considered the gold standard for studying effects, the complexity of the effects in the area of housing and mental illness strains the limits of this methodology. Part of the problem is the need for multiple experimental and control conditions. For example, a complete test of the relative roles of housing and services in mental health outcomes would require a service intervention and its control, a housing intervention and its control, and an additional nonintervention group. The difference between access to and attainment of independent housing adds another layer of complexity to the design. Also at issue is the ability to implement the experiment as designed without contamination, bias from differential attrition, and other threats to generalizability.

This discussion of the problems inherent in the experimental method is not meant to discourage its application. Rather, it is a call for extra precautions to ensure that the experimental design is consistent with the policy questions being asked, that the interventions are implemented as designed, and that the experimental sites are not unique, so that results are generalizable. It also suggests that opportunities for nonexperimental studies should be pursued whenever it is possible to use sophisticated statistical techniques to simulate experimental conditions. Such an approach has been frequently used in sociology and economics, and it has been strengthened substantially by the merging of data from administrative records and sample surveys.

More sophisticated analytic methods are also required. The pristine conditions of the laboratory cannot be applied to social science studies, which makes correlational analysis inherently inadequate. All research designs, whether nonexperimental, quasi-experimental, or experimental, typically require multivariate modeling. Such models need to account for a comprehensive set of characteristics, selection bias, and possible effects of unmeasured or unobserved attributes.

Turning these recommendations into reality will, of course, require significant funding from government agencies and private foundations. The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and the Center for Mental Health Services supported some of the studies reviewed here; however, funds have been limited, and the continuity of interest required to build a coherent body of knowledge has been lacking. The recent release of the Surgeon General's report on mental illness (39) and the NIMH report (40), which identifies "contextual influences on mental illness and its care" as a prime target for intensified study, raises the hope that continuous interest and support may finally be forthcoming.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by contract 98M00212501D with the Center for Mental Health Services of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The author acknowledges the encouragement and support of Walter Leginski, Ph.D., Fran Randolph, Dr.P.H., and Pam Fisher, Ph.D., and the research assistance of Amy Robie and Sally Katz.

The author is with the Institute for Policy Studies at Johns Hopkins University, Wyman Park Building, 3400 North Charles Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21218 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Studies included in the literature review, by type of housing conceptualization, and selected characteristics of the study samples1

1 Data are based on the total sample, including, where relevant, experimental and control or multiple comparison groups, and were obtained directly or calculated from group percentagesArticles that contain multiple conceptualizations are presented only once under the first model to which they apply; thus, Hough et al. (9) is not repeated under Housing as an input, and four studies (6,9,11,30) are not repeated under Housing as an input and an outcome.

|

Table 2. Design features of studies in the literature review that used housing as an outcome

|

Table 3. Design features of studies in the literature review that used housing as an input

|

Table 4. Design features of studies in the literature review that used housing as an input and an outcome

1. Kessler R, Berglund P, Leif P, et al: The 12-month prevalence and correlates of serious mental illness, in Mental Health, United States, 1996. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Sonnenschein MS. DHHS pub (SMA)96-3098. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 1996Google Scholar

2. Skinner E, Steinwachs D, Kasper J: Family perspectives on the service needs of people with serious and persistent mental illness: characteristics of families and consumers. Innovations and Research 1:23-30, 1992Google Scholar

3. Newman SJ: Housing and Mental Illness: A Critical Review of the Literature. Washington, DC, Urban Institute, 2001Google Scholar

4. Cournos F: The impact of environmental factors on outcome in residential programs. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:848-852, 1987Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Bond G, Witheridge T, Wasmer D, et al: A comparison of two crisis housing alternatives to psychiatric hospitalization. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:177-183, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Lehman AF, Slaughter J, Myers C: Quality of life in alternative residential settings. Psychiatric Quarterly 62:35-49, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Uehara ES: Race, gender, and housing inequality: an exploration of the correlates of low-quality housing among clients diagnosed with severe and persistent mental illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 35:309-321, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Mowbray CT, Bybee D: The importance of context in understanding homelessness and mental illness: lessons learned from a research demonstration project. Research on Social Work Practice 8:172-199, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Hough RL, Wood PA, Hurlburt MS, et al: Using Independent Housing and Supportive Services With the Homeless Mentally Ill: An Eighteen-Month Outcome Study. Draft, 1995Google Scholar

10. Hurlburt MS, Hough RL, Wood PA: Effects of substance abuse on housing stability of homeless mentally ill persons in supported housing. Psychiatric Services 47:731-736, 1996Link, Google Scholar

11. Lehman AF, Dixon LB, Kernan E, et al: A randomized trial of assertive community treatment for homeless persons with severe mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:1038-1043, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Goering P, Wasylenki D, Lindsay S, et al: Process and outcome in a hostel outreach program for homeless clients with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 67:607-617, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Baker F, Douglas C: Housing environments and community adjustment of severely mentally ill persons. Community Mental Health Journal 26:497-505, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Coulton CJ, Holland TP, Fitch V: Person-environment congruence and psychiatric patient outcome in community care homes. Administration in Mental Health 12:71-88, 1984Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Linn MW, Klett CJ, Caffey EM: Foster home characteristics and psychiatric patient outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:129-132, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Nagy MP, Fisher GA, Tessler RC: Effects of facility characteristics on the social adjustment of mentally ill residents of board-and-care homes. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:1281-1286, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

17. Davies MA, Bromet EJ, Schulz SC, et al: Community adjustment of chronic schizophrenic patients in urban and rural settings. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:824-830, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

18. Depp FC, Dawkins JE, Selzer N, et al: Subsidized housing for the mentally ill. Social Work Research and Abstracts 22:3-7, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Earls M, Nelson G: The relationship between long-term psychiatric clients' psychological well-being and their perceptions of housing and social support. American Journal of Community Psychology 16:279-293, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Nelson G, Hall GB, Walsh-Bowers R: The relationship between housing characteristics, emotional well-being, and the personal empowerment of psychiatric consumer/survivors. Community Mental Health Journal 34:57-69, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Lipton FR, Nutt S, Sabatini A: Housing the homeless mentally ill: a longitudinal study of a treatment approach. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:40-45, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

22. Trute B, Segal SP: Census tract predictors and the social integration of sheltered care residents. Social Psychiatry 11:153-161, 1976Google Scholar

23. Segal SP, Silverman C, Baumohl J: Seeking person-environment fit in community care placement. Journal of Social Issues 45:49-64, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Dixon L, Krauss N, Myers P, et al: Clinical and treatment correlates of access to Section 8 certificates for homeless mentally ill persons. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:1196-1200, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

25. Goldfinger SM, Schutt RK, Tolomiczendo GS, et al: Housing persons who are homeless and mentally ill: independent living or evolving consumer households? In Mentally Ill and Homeless: Special Programs for Special Needs. Edited by Breakey W, Thompson J. Australia, Harwood Academic Publishers, 1997Google Scholar

26. Goldfinger SM, Schutt RK, Tolomiczendo GS, et al: Housing placement and subsequent days homeless among formerly homeless adults with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 50:674-679, 1999Link, Google Scholar

27. Dickey B, Gonzalez O, Latimer E, et al: Use of mental health services by formerly homeless adults residing in group and independent housing. Psychiatric Services 47:152-158, 1996Link, Google Scholar

28. Dickey B, Latimer E, Powers K, et al: Housing costs for adults who are mentally ill and formerly homeless. Journal of Mental Health Administration 24:291-305, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Wood PA, Hurlburt MS, Hough RL, et al: Longitudinal assessment of family support among homeless mentally ill participants in a supported housing program. Journal of Community Psychology 6:327-344, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Newman SJ, Reschovsky JD, Kaneda K, et al: The effects of independent living on persons with chronic mental illness: an assessment of the Section 8 certificate program. Milbank Quarterly 72:171-198, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Newman SJ, Harkness J, Galster G, et al: Bricks and behavior: the development and operating costs of housing for persons with mental illness. Real Estate Economics 29:277-304, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

32. Hurlburt MS, Wood PA, Hough RL: Providing independent housing for the mentally ill: a novel approach to evaluating long-term longitudinal housing patterns. Journal of Community Psychology 24:291-310, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

33. Newman SJ, Reschovsky JD: Neighborhood locations of Section 8 housing certificate users with and without mental illness. Psychiatric Services 47:392-397, 1996Link, Google Scholar

34. Making a Difference: Interim Status Report of the McKinney Demonstration Program for Homeless Adults With Serious Mental Illness. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 1994Google Scholar

35. Braun P, Kochansky G, Shapiro R, et al: Overview: deinstitutionalization of psychiatric patients, a critical review of outcome studies. American Journal of Psychiatry 138:736-749, 1981Link, Google Scholar

36. Goldman H, Morrissey J: The alchemy of mental health policy: homelessness and the fourth cycle of reform. American Journal of Public Health 75:727-731, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics:1980 Long-Term Health Care Minimum Dataset. Hyattsville, Md, National Center for Health Statistics, Public Health Service, 1980Google Scholar

38. National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics:1987 Annual Report. Hyattsville, Md, National Center for Health Statistics, Public Health Service, 1988Google Scholar

39. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1999Google Scholar

40. Translating Behavioral Science Into Action. Bethesda, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 2000Google Scholar