Public Costs of Better Mental Health Services for Children and Adolescents

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study evaluated how improved community mental health services for youths affect public expenditures in other sectors, including inpatient hospitalization, the juvenile justice system, the child welfare system, and the special education system. METHODS: Participants were youths aged six to 17 years who received services through a mental health agency in one of a matched pair of communities. One community delivered mental health services according to the principles of systems of care (N=220). The comparison community delivered mental health services but did not provide for the interagency integration of services (N=211). The analyses are based on administrative and interview data. RESULTS: Preliminary analyses revealed that mental health services delivered as part of a system-of-care approach are more expensive. However, incorporating expenditures in other sectors reduced the between-site gap in expenditures from 81 to 18 percent. This estimate is robust to changes in analytical methods as well as adjustments for differences between the two sites in the baseline characteristics of participants. CONCLUSIONS: These findings suggest that reduced expenditures in other sectors that serve youths substantially, but only partially, offset the costs of improved mental health services. The full fiscal impact of improved mental health services can be assessed only in the context of their impact on other sectors.

Children and adolescents treated in public mental health systems are frequently involved in multiple systems that serve youths. These systems include juvenile justice (1,2,3) and child welfare (1). In addition, these youths frequently receive special services at school, including, but not limited to, special education (4).

Policy makers know that the resulting costs can be quite high (5). Policy and societal concerns extend beyond the amount of these expenditures to questions of whether they represent a misallocation of resources (6). There are reasons to suspect this may be the case. These other systems often are oblivious to the mental health needs of youths or are ill equipped to handle problems identified. A key question is whether these same expenditures could be targeted more directly to the mental health needs of these youths. Such targeting might produce better outcomes, lower public expenditures, or both.

These issues lie at the heart of recent efforts to improve the delivery of mental health services through cross-system integration. One such effort is the system-of-care approach. This approach reflects a public health perspective; responsibility for meeting the mental health needs of youths resides at the community level rather than with a single agency. Under such a system the mental health sector coordinates and delivers services in conjunction with other agencies that serve youths, such as the juvenile justice and child welfare system. The required interagency integration can exist at multiple levels—financing, administration, referral patterns, and training. When implemented, systems of care also change the types of mental health services delivered. In particular, inpatient care is replaced with community-based alternatives, such as day treatment or partial hospitalization. The overall milieu of service delivery is changed as well. According to the system-of-care philosophy, care should be individualized, family friendly, and culturally appropriate (7).

The effects of a system of care on other sectors are likely to be complex and reflect a mix of cost shifting and cost offset. Cost shifting occurs when the source of payment shifts from one payee to another while the type or content of services received does not change (8). Cost offset involves improvements in a youth's condition that reduce the need for services in other sectors. At this time, no research exists on how systems of care affect expenditures by other systems that serve youths.

One possible basis for documenting and understanding the fiscal impact of the system-of-care model involves the Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services for Children and Their Families Program, which is funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. This program fosters systems of care in the public sector throughout the country. Sixty-seven communities are participating in an evaluation that comprises quantitative and qualitative elements; the former includes a longitudinal study of youths served at each site. Three system-of-care sites were paired with three matched communities that were not operating under the system-of-care approach.

This study examined data from one of those pairs—a system-of-care community in Stark County, Ohio, and a comparison community in Mahoning County, Ohio. In Stark County, integration occurs at both the administrative and operational levels among the agencies that serve youths (9). At the administrative level, representatives of the different agencies participate in planning service use. At the operational level, mental health staff are stationed in the offices and facilities maintained by the other systems, such as the juvenile justice system. The mental health agency also provides training for personnel in the other systems—for example, employees of the mental health agency provide juvenile justice personnel with training in the principles of multisystemic therapy. This study used a quasi-experimental design and examined the impact of the system of care on public expenditures in the special education system, the juvenile justice system, and the child welfare system.

Methods

Since 1994 the Center for Mental Health Services (CMHS) within the Department of Health and Human Services has funded the development of systems of care through the Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services for Children and Their Families Program. The CMHS program provides communities with seed money to establish an administrative structure for the system of care. Communities draw on Medicaid, block grants, and other sources to finance services.

Study design

CMHS also funded a national, multisite evaluation, which provided the data for this study (10). This evaluation used a quasi-experimental study design to match and compare three system-of-care communities with three similar communities. One pair was a system of care in Canton, Ohio, in Stark County and a comparison community in Youngstown, Ohio, in Mahoning County. Established in the 1970s and administered by the Stark County Family Council, the system of care in Stark County links families with agencies that provide various services, including education, mental health, child, health, and juvenile justice (11). The target population for the system of care comprises youths at risk of out-of-home placement who are involved in multiple sectors, including the juvenile justice and child welfare systems. Service delivery in Mahoning County, the comparison county, revolves around a community mental health center that provides mainly outpatient care; however, the agency operated a short-term crisis residential center during the early years of the project. Mahoning County's services represent treatment as usual.

To evaluate the effect of the system of care on costs and mental health outcomes, a sample of 449 youths aged six to 17 years with serious emotional and behavioral problems who were using mental health services at the two hub agencies were recruited for a longitudinal study. Eighteen participants were excluded from these analyses because of missing data, leaving 220 participants from the system-of-care site and 211 youths from the comparison site. Study enrollment began in September 1997 and continued through October 1999; follow-up data collection continued through December 2000. The analyses of costs presented here focus on the first 12 months after entry into the study. Data were collected under approval from the Office of Management and Budget and in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Interview data

Data on child and family outcomes were collected through face-to-face interviews that were conducted with participating youths and their caregivers. Interviews were conducted at study entry and then at six-month intervals. Interview data provided measures of treatment outcomes and were used to examine whether the baseline characteristics of study participants differed between the study sites.

In addition to obtaining information about the demographic characteristics of the family, the interviews included well-accepted measures of the child's mental health, such as the Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment Scale (CAFAS), which assesses functioning in eight different life domains (12), and the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), which measures symptoms (13).

Data from the management information system

The participating mental health centers in the two communities are private behavioral health treatment organizations. The data for the core mental health services that were provided and the cost of these services came from each agency's management information system (MIS), which is used for billing purposes. Services included in the data consisted of intake and assessment services, case management, medication monitoring, and individual and group counseling. The system-of-care site also offered day treatment, and the comparison site offered a short-term crisis residential center during part of the study. Data on provision of these services are recorded in the MIS for that site.

Data from other agencies

Although MIS data from the two sites were fairly comparable, each was limited in the scope of services included. MIS data did not include contracted services, primarily inpatient care. Data on these services were collected from the records of the two primary inpatient facilities in each county.

The MIS data also did not include information on other sectors. For that reason, we collected services and budget information from 12 agencies and providers in the child welfare, juvenile justice, and special education sectors. Child welfare data were obtained from the child welfare departments in the two communities. Each county provided MIS data on payments to foster parents and for group home placements. Data on juvenile justice expenditures were limited to detention costs and consisted of two types of facilities—a short-term juvenile detention center maintained by each county and a long-term detention facility maintained by the state for serious offenders in both counties. The long-term detention facility served youths from both counties. Obtaining special education data provided a greater challenge because a countywide cost database does not exist for all school districts. Therefore, data collection efforts focused on two special education providers in each county—the largest urban school district and the special education program that serves rural areas.

Per diem rates were determined by using budgetary information for each year from 1997 to 2000. Although these rates are not discussed extensively here because of space limitations, per diem rates were fairly comparable across sites, in terms of both their actual values and the methods used to calculate them. The full set of per-unit costs and a discussion of the methods used are available from the first author.

A key issue involves the interpretation of the per diem rates and the expenditures based on them. Every economic analysis has a perspective from which expenditures or costs are calculated (14,15); this study employed a public or taxpayer perspective. By using this method our tabulations captured the economic impact of the system of care on public budgets. For that reason, our per-unit costs correspond to the rate at which one sector of the government reimburses another. Therefore, our tabulations represent expenditures rather than costs per se in the sense that economists use the term—that is, marginal, opportunity costs.

Statistical methods

To simplify the presentation, our analyses present untransformed expenditures. (Economists have developed the smearing estimate and have applied the generalized linear model to handle the skewed distribution of expenditures [16,17,18,19]). Although these methods are not presented here, we have employed them, and they produce results that are very similar to those reported below.) We did decompose differences in expenditures by using the two-part model. This technique separates between-group differences into two elements. The first element involves the proportion of youths and families in each group who were served in a particular sector; the second involves the cost of services for those youths and families receiving those services.

Results

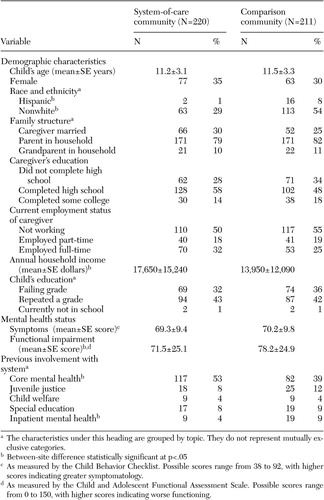

Table 1 describes the baseline characteristics of study participants at the two sites. Youths enrolled in the study were fairly similar in the two communities. However, participants differed in their race and ethnicity and their family income. In particular, youths in the system-of-care community were more likely to be white (71 percent compared with 46 percent; χ2=28.16, df=1, p<.01) and considerably less likely to be Hispanic (1 percent compared with 8 percent; χ2=11.99, df=1, p<.01). Families in the system-of-care site reported higher average annual incomes ($17,650 compared with $13,950; t=2.77, df=424, p=.01). Other family demographic characteristics, such as the level of education and the employment status of the caregivers, were similar across the two groups. For mental health status, youths had similar levels of clinical symptoms at intake, as measured by the CBCL, but children in the comparison community had higher levels of functional impairment, as measured by the CAFAS (a mean score of 78.18 compared with a mean score of 71.49; t=-2.76, df=422, p=.01).

Table 1 also shows whether the youths were involved with the agencies before study entry. Youths in the system of care were less likely to have received inpatient services before study entry (4 percent compared with 9 percent; χ2=4.28, df=1, p=.04) and more likely to have been served by the core mental health agency in their community (53 percent compared with 39 percent; χ2=8.89, df=1, p<.01). Youths in the system of care were less likely to have been involved with the juvenile justice system before study entry (8 percent compared with 12 percent), but this difference was not statistically significant.

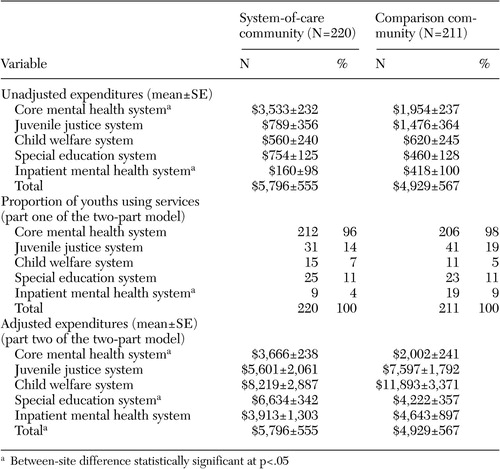

The first section of Table 2 presents unadjusted expenditures for each of the key sectors as well as total expenditures. Consistent with research on other service innovations, average expenditures for mental health services by the core agency were higher under the system of care ($3,533 compared with $1,954; t=4.75, df=429, p<.01). However, these differences hide substantial variation in the dynamics of service use. In supplemental analyses, we examined the timing of these expenditures and found that youths in the system of care remained in treatment longer and were less likely to return for additional care after an initial treatment episode (unpublished manuscript, Foster EM, Xuan F, 2004). In the data presented here, expenditures for the juvenile justice system and for inpatient services were higher in the comparison community. However, when simple t tests were done, only inpatient services were significant at the 5 percent level.

The figures in the first section average across individuals who do and do not have expenditures in a given sector, and the simple t test does not reflect the skewed distribution of expenditures. For that reason, the last two sections of Table 2 decompose expenditures into the two parts of the two-part model: the likelihood of involvement in a sector and expenditures conditional on being involved in that sector. Youths in the comparison site were significantly more likely to receive inpatient services (9 percent compared with 4 percent; χ2=4.28, df=1, p=.04). Youths in the comparison site were also more likely to be involved in the juvenile justice system (19 percent compared with 14 percent), although this finding was not statistically significant.

The last section of Table 2 describes expenditures in the different sectors among individuals who were involved in those sectors. When the data were limited to individuals involved in the juvenile justice system, average expenditures in that system were lower under the system of care ($5,601 compared with $7,597). This difference in cost reinforces the fact that fewer youths in the system of care were involved with the juvenile justice system. However, average expenditures for special education were actually higher under the system of care ($6,634 compared with $4,222; t=3.55, df=46, p<.01).

Adding the other expenditures reduces the between-site difference in expenditures from $1,579 to $868. When expenditures in other sectors were incorporated in the analyses, the between-site gap decreased from 81 to 18 percent. Using the bootstrapping resampling method, we determined that this reduction was statistically significant (p=.04). With bootstrapping the distribution of a sample statistic is determined through simulation. The method involves drawing repeated samples from the observed sample, which is treated as the population. This method is justifiable under fairly weak assumptions and avoids the need to make distributional assumptions.

These findings were quite robust. In supplemental analyses, we adjusted these sector-specific estimates with the baseline characteristics from Table 1 to ensure that study participants were comparable in the two sites. The results of these analyses were similar to those presented here and are available from the first author.

Discussion and conclusions

Research on youths' mental health services suggests that higher-quality mental health services may be more expensive. Motivated by high inpatient expenditures, attempts at reform originally held out the hope that services could be improved while expenditures were reduced. Savings would be achieved by shifting children from inpatient care to treatment in less expensive settings, such as partial hospitalization or various forms of outpatient therapy. But research has not confirmed these initial hopes (20,21,22).

However, research generally has ignored the impact of mental health services on other sectors that serve youths. The analyses presented here suggest that those sectors are important for understanding the full fiscal impact of the system of care. In particular, expenditures for core mental health services were 81 percent higher for the system-of-care site compared with the matched site; after other public expenditures were included, the difference in cost between the sites dropped to 18 percent. This change was largely driven by reductions in cost in the juvenile justice and child welfare sectors for youths served in the system of care.

Whether this reduction represents cost shifting or cost offset is unclear. Future work could link these analyses to changes in a youth's mental health status to determine whether involvement in other sectors was mediated by improvements in his or her symptoms or functioning.

The study has several limitations. The first and principal among these is inherent to a quasi-experimental study design, which these analyses depend on. The two communities may have differed in more ways than whether they implemented a system of care. It is somewhat reassuring that the two communities are in the same region of the same state. As a result, some relevant factors, such as the generosity of the Medicaid program, are held constant.

A related limitation is that we have data only on youths who received at least some mental health services. If the system of care affects the number and type of youths who receive services, participants at the two sites may not be comparable. However, we compared the baseline characteristics of study participants for the two sites and found that the sites were similar in many ways. Furthermore, the between-site difference in total public expenditures did not change when we adjusted for baseline differences in mental health and other characteristics between the two sites.

A key feature of our study is that available data do not include youths who did not receive mental health services. As a result, the analyses presented here should be viewed as conservative. A full account of the fiscal impact of the system of care would recognize that this system treats many youths who are in need of mental health services who would otherwise not be served. It seems likely that these youths are creating substantial costs for other systems; our results suggest that those expenditures might be reduced if these youths received mental health services.

A third limitation involves the coverage of costs in other sectors that serve youths. Although we have captured services that represent the largest expenditures, in each sector there is resource use that was not included in our analyses. For example, our analyses of costs for the juvenile justice system included detention but not court costs or probation and aftercare services. Similarly, we have not captured general administrative costs. In the case of child welfare, for example, these costs could be quite large. If, as seems likely, these omitted costs are proportional to the costs we analyzed, their inclusion would narrow the between-site gap still further.

Finally, when interpreting these findings, it is important to note that we have not conducted a full economic analysis. When judged from a societal perspective, reduced expenditures in other sectors that serve youths represent only a subset of the possible benefits of improved treatment. The benefits of improved school performance, for example, extend far beyond reductions in expenditures on special education. Children involved with a system of care may be more likely to finish high school, transition to adulthood successfully, and become future taxpayers (23). Incorporating effects like these represents the next step in the economic analysis of systems of care. Such an analysis would capture the full economic impact of better mental health services and provide a more comprehensive basis for policy makers to use in evaluating systems of care (6).

Acknowledgments

Data were collected through the national evaluation of the Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services for Children and Their Families Program that was funded by grant 280-94-0012 from the Center for Mental Health Services. The authors thank Paula Clarke, Ph.D., who provided the necessary data and budget information. The authors also thank Allison Olchowski, M.S., Elizabeth Gifford, Ph.D., and Peter Kemper, Ph.D., for helpful comments.

Dr. Foster is affiliated with the department of health policy and administration and the Methodology Center at Pennsylvania State University, 116 Henderson Building North, University Park, Pennsylvania 16802-4705 (e-mail, [email protected]). Mr. Connor is with ORC Macro, Inc., in Atlanta.

|

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of youths aged six to 17 years who received services through a community system of care or a mental health facility in a comparison community

|

Table 2. Expenditures for services received in the first 12 months after youths entered the study and number of youths who used services in each sector

1. Banks SM, Pandiani JA: Mental health and criminal justice caseload overlap in five counties, in A Systems of Care for Children's Mental Health: Expanding the Research Base. Edited by Newman C, Liberton CJ, Kutash K, et al. Tampa, Fla, Research and Training Center for Children's Mental Health, 2002Google Scholar

2. Libby AM, Cuellar AE, Snowden LR., et al: Substitution in a medical mental health carve-out: services and costs. Journal of Health Care Finance 28:11–23, 2002Medline, Google Scholar

3. Foster EM, Qaseem A, Connor T: Can better mental health services reduce juvenile justice involvement? American Journal of Public Health 94:859–865, 2004Google Scholar

4. Twenty-third Annual Report to Congress on the Implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, US Department of Education, 2001Google Scholar

5. Connecticut Title IV-E Waiver Demonstration Program: Final Report. Atlanta, Ga, ORC Macro, Inc, 2003Google Scholar

6. Foster EM, Connor T: A Road Map for Costs Analyses of Systems of Care in Outcomes for Children and Youth with Emotional and Behavioral Disorders and Their Families: Programs and Evaluation Best Practice, 2nd ed. Edited by Epstein M, Kutash K, Duchnowski A. Austin, Tex, Pro-Ed, in pressGoogle Scholar

7. Stroul BA, Friedman RM: The System of Care Concept and Philosophy in Children's Mental Health: Creating Systems of Care in a Changing Society. Edited by Stroul BA. Baltimore, Md, Paul H. Brookes Publishing, 1996Google Scholar

8. Norton EC, Lindrooth RC, Dickey B: Cost-shifting in managed care. Mental Health Services Research 1:185–196, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Ragan M: Building comprehensive human service systems. Focus 22:58–62, 2003Google Scholar

10. Annual Report to Congress on the Evaluation of the Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services for Children and Their Families Program, 1999. Atlanta, Ga, ORC Macro, Center for Mental Health Services, 1999Google Scholar

11. Bickman L, Summerfelt TW, Firth JM, et al: The Stark County Evaluation Project in Valuating Mental Health Services: How do Programs for Children "Work" in the Real World? Edited by Northrup DA, Nixon C. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage Publications, 1997Google Scholar

12. Hodges K: Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment Scale (CAFAS). Ypsilanti, Mich, Eastern Michigan University, department of psychology, 1990Google Scholar

13. Achenbach TM: Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and 1991 Profile. Burlington, Vt, University of Vermont, 1991Google Scholar

14. Hargreaves WA, Shumway M, Hu TW, et al: Cost-Outcome Methods for Mental Health. New York, Academic Press, 1998Google Scholar

15. Foster EM, Jones D, Dodge KA: Issues in the economic evaluation of prevention programs. Applied Developmental Science 7:74–84, 2003Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Duan N: Smearing estimate: a nonparametric retransformation method. Journal of the American Statistical Association 78:605–610, 1983Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Manning WG: The logged dependent variable, heteroskedasticity, and the retransformation problem. Journal of health Economics 17:283–295, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Manning WG, Mullahy J: Estimating log models: to transform or not to transform. Journal of Health Economics 20:461–494, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Jones AM: Health econometrics, in Handbook of Health Economics: Vol 1. Edited by Culyer AJ, Newhouse JP. New York, Elsevier, 2000Google Scholar

20. Bickman L, Guthrie PR, Foster EM, et al: Evaluating Managed Mental Health Services: The Fort Bragg experiment. New York, Plenum Press, 1995Google Scholar

21. Foster EM, Summerfelt WT, Saunders R: The costs of mental health services under the Fort Bragg Demonstration. Journal of Mental Health Administration 23:92–106, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Foster EM, Bickman L: Refining the costs analyses of the Fort Bragg evaluation: the impact of cost offset and cost shifting. Mental Health Services Research 2:13–25, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Haveman RH, Wolfe BL: Schooling and economic well-being: the role of nonmarket effects. Journal of Human Resources 19:376–407, 1984Google Scholar