Consumer Views of Representative Payee Use of Disability Funds to Leverage Treatment Adherence

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Although representative payee arrangements are common among people with psychiatric disabilities, only a small body of research has investigated how consumers feel about representative payees' use of disability funds to attempt to improve treatment adherence. METHODS: Consumers who were in treatment for a recently documented diagnosis of schizophrenia or a related disorder (N=104) were interviewed to assess their perceptions of the use of disability funds and other legal pressures to attempt to improve treatment adherence. RESULTS: Most consumers in the sample (65 percent) did not agree that withholding money was a useful method to improve treatment adherence. Multivariate analyses indicated that participants were more likely to agree that use of money as leverage was helpful if they also felt that other legal pressures were helpful for improving adherence and if they felt free to do as they wanted regarding their mental health treatment. On the other hand, participants were less likely to endorse the benefits of money used as leverage if they had at least a high school education and if they reported abusing substances in the past month. CONCLUSIONS: The results of this study point to factors that mediate the potentially negative effects of perceived coercion that are sometimes associated with representative payee arrangements. Leverage of disability funds will likely have an optimal effect if combined with efforts to enhance a sense of self-determination. Conversely, consumers with more education may be less open to this practice, possibly because of perceived stigma related to not being able to control their own finances.

More than 2.6 million people in the United States between the ages of 18 and 65 years receive Social Security Disability Insurance or Supplemental Security Income as a result of psychiatric disabilities (1,2). However, recipients may have cognitive deficits that impair their ability to manage money (3), or they may use these benefits to purchase illicit drugs or alcohol (4,5). For recipients who are deemed unable to manage finances, the Social Security Administration (SSA) appoints a representative payee (6). On the basis of 2003 data from the SSA, an estimated 800,000 individuals with psychiatric disabilities are assigned a representative payee (1,2,6).

A representative payee is an individual or institution that directly receives disability checks and ensures that the recipient has his or her basic needs met—such as for food, shelter, and clothing—and obtains proper medical, dental, and eye care (7). Discretionary funds that remain after basic needs have been covered are limited; usually they are less than $100. Although not a chief function of the legal arrangement, representative payees may use discretionary funds as leverage to improve treatment adherence (8,9).

Research has examined whether people with psychiatric disabilities benefit from having a representative payee (10). Studies have indicated that representative payee arrangements are associated with reduced homelessness (11), decreased victimization (12), greater treatment participation (13), and fewer days in psychiatric hospitals (14). For example, the Pathways project provided a specialized assertive community treatment program to homeless persons. Participants in the program allowed Pathways to become their representative payee and experienced significantly decreased homelessness in both randomized and quasi-experimental studies (15,16). The impact of representative payees on substance abuse is less clear. One study demonstrated that monetary reinforcement increased abstinence among patients with dual diagnoses (17), whereas other studies have indicated that representative payee assignment had no effect on reducing substance abuse (18,19). Research has also shown that representative payee arrangements can improve treatment adherence (13,20).

However, representative payeeship has potential downsides. In particular, research suggests that representative payees might use disability funds as leverage in ways that consumers with psychiatric disabilities perceive as coercive. In one study, approximately one-third of participants with psychiatric disabilities reported that they believed their money would be withheld if they did not adhere to treatment (21). Family and clinicians were also more likely to use money to leverage adherence to treatment when acting as the representative payee (21). Studies have found that the use of such monetary therapeutic limit setting can lead to negative outcomes among consumers, including increased drug abuse and decreased functioning (22). Even when a consumer does not have a representative payee, clinicians may warn consumers that a representative payee needs to be assigned if the consumer does not adhere to treatment (22). Finally, Dixon and colleagues (23) found that nearly half of case-manager representative payees reported incidents in which consumers became verbally abusive in response to issues about the management of the disability funds.

Despite the prevalence and possible benefits of representative payeeship, few studies have examined issues of coercion that are associated with the use of disability funds to leverage adherence. The purpose of the study reported here was to explore consumers' opinions about representative payees' use of disability funds to attempt to improve treatment adherence.

Methods

Sample

Data were collected from 2001 to 2002 from persons with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, including schizoaffective and schizophreniform disorders, who resided in the Piedmont region of North Carolina. These persons had recently completed an observational study of schizophrenia treatment under usual care conditions and had consented to be contacted so they could be provided with information about the study reported here. Approval for the survey was obtained from Duke University's institutional review board. These persons were eligible for our study if they were adult patients who were in treatment for a recently documented DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or schizophreniform disorder. After participants were given a complete description of the study, written informed consent was obtained.

Even after giving informed consent to participate, a small number of participants demonstrated potential difficulty comprehending the relatively complex questions in the interview. In those cases, the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire was administered (24). If the participant made four or more errors on this instrument, the interview was stopped and his or her data were not used. Eleven participants' data were excluded on these criteria, but it should be noted that they did not differ from the remaining participants in gender, race or ethnicity, age, and whether they felt money was useful as leverage for treatment adherence. A total of 104 participants were included in our final sample.

Instruments

Demographic information was obtained by self-report and included gender, race or ethnicity, marital status, age, and number of years of education. Consumers were also asked about drug or alcohol use in the past month. Substance abuse was measured by self-reported abuse of alcohol or illicit drugs in the past month. The symptom severity section of the Schizophrenia Outcomes Module baseline assessment was used to assess symptoms (25). In this 11-item assessment consumers reported the severity of symptoms of psychosis and depression in the past week on a 4-point scale, from 0, not at all bothered by that symptom, to 4, greatly bothered. Symptom variables were dichotomized at the median because their distributions were negatively skewed. An overall symptom scale was calculated from the mean of all items, and a depression measure was calculated from the mean of a four-item subset (alpha=.88 for the sample). Insight was assessed with the Insight and Treatment Attitudes Questionnaire, which contains 11 items on consumers' views of their mental health problems and their need for mental health treatment in the past, currently, and in the future (26). For this measure, 22 represents the highest level of insight and zero the lowest (alpha=.82 for the sample).

Participants were asked to respond to the following statement to determine whether they thought they were better off when legal pressures (for example, warnings of jail, involuntary hospitalization, or eviction) were used to encourage them to keep appointments or take medications: "On the whole, I am better off because of legal pressures to keep appointments." It could be argued that this question does not apply to participants who are not currently subject to legal mechanisms. However, given the participants' diagnoses, it is reasonable to assume that most had been hospitalized and had encountered legal pressures at some point. Even for those who were not hospitalized, the potential to be mandated to legal mechanisms still arguably denotes a form of legal pressure. Rosenheck and Neale (22) indicated that warning consumers that a representative payee may need to be assigned is not uncommon and illustrates that legal pressures exist for consumers whose adherence to treatment is not currently leveraged by a legal mechanism.

Information about disability funds and finances was also collected. Specifically, participants were asked to report their income, whether they felt that they had enough money to cover expenses, and whether they had ever had a representative payee. Participants were asked to respond to the following statement to determine whether they perceived coercion in their mental health treatment: "I feel free to do as I want regarding my mental health treatment." Finally, the dependent variable involved consumers' opinion about the usefulness of money specifically as a leverage for treatment adherence. For the question about representative payeeship, participants rated the following statement by using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 5, strongly agree, to 1, strongly disagree: "One way to help people with serious mental health problems to stay well is to hold back their money unless they keep going to treatment."

Analysis

Analyses were conducted with SAS version 8.0. We first present descriptive statistics for clinical and demographic characteristics. Second, we present chi square analyses that were used to ascertain bivariate associations between opinions about money leverage and clinical and demographic characteristics. Finally, we present stepwise logistic regression analyses in which independent variables were excluded from subsequent analyses if they did not meet a probability level of .10. Odds ratios produced by this technique estimate the average change in the odds of a predicted outcome (for example, agreeing that money as leverage is helpful) associated with exposure to independent variables (for example, substance abuse). The log likelihood chi square analyses test the overall significance of a given logistic regression model.

Results

Most participants were male (57 participants, or 55 percent) and black (76 participants, or 73 percent), and most had completed high school (65 participants, or 63 percent). Most participants were older than 40 years (65 participants, or 63 percent) and not married (91 participants, or 88 percent). Clinically, the sample showed high insight on the Insight and Treatment Attitudes Questionnaire (82 participants, or 79 percent). Furthermore, 45 participants (43 percent) stated that they had fewer than three current psychotic symptoms, 65 participants (63 percent) stated that they had fewer than three current depressive symptoms, and only 14 participants (14 percent) stated that they had abused substances in the past month.

Financially, 23 participants (22 percent) reported an income greater than $15,000 a year, and 58 participants (56 percent) indicated that they had had a representative payee at some point. Eighty-four participants (81 percent) reported that legal pressures were helpful for keeping them in treatment, and 68 participants (65 percent) reported that they felt free to do what they wanted for their mental health treatment.

A majority of the sample (68 participants, or 65 percent) either strongly disagreed or disagreed with the statement: "One way to help people with serious mental health problems to stay well is to hold back their money unless they keep going to treatment." In bivariate analyses, clinical and demographic variables were not associated with these opinions. Compared with participants who did not see legal pressures in general as beneficial, those who perceived that these pressures were helpful were significantly more likely to perceive that money as leverage was beneficial (χ2=6.62, df=1, p=.01). Furthermore, feeling as though they were free to do as they wanted in regard to their mental health treatment was also associated with positive views of money as leverage (χ2=4.84, df=1, p=.02).

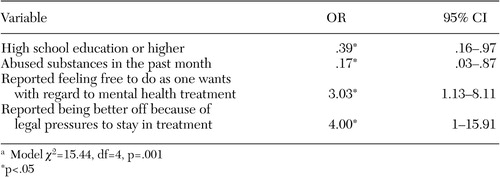

Table 1 displays the results of multivariate analyses of factors that are associated with believing that financial leverage is useful. This model was statistically significant (χ2=15.44, df=4, p=.001). In the stepwise selection process, four variables were significant in the final model. Participants were more likely to agree that financial leverage was helpful if they also felt that other legal pressures were helpful for improving adherence and if they felt as though they were free to do as they wanted regarding their mental health treatment. On the other hand, participants were less likely to endorse the benefits of financial leverage if they had at least a high school education and if they reported abusing substances in the past month.

Discussion

A majority of consumers (65 percent) reported that they viewed attempts to improve treatment adherence by withholding disability benefits as unhelpful.Multivariate analyses indicated that participants with at least a high school education and who reported abusing substances in the past month were less likely to see withholding money as useful. Conversely, participants who thought that legal pressures were helpful and felt that they were free to do what they wanted regarding their treatment were more likely to endorse the benefits of using money as leverage.

It is important to note that use of disability funds as leverage to improve adherence can backfire if it is implemented incorrectly. If a consumer perceives these practices to be coercive, then family relationships or the therapeutic alliance—both of which are related to better adherence (27)—can be undermined. The data provide some clues about mediating the potentially negative effects of perceived coercion that are sometimes associated with representative payeeship. First, consumer choice was associated with opinions about money leverage. Monahan and colleagues (10) indicated that consumers' perceptions of coercion in legal processes are largely affected by whether consumers believe that they are treated with respect and given a chance to express their preferences, that is, are afforded procedural justice (28,29,30). Consistent with the results of other empirical studies (31,32,33), the results reported here suggest that representative payee status alone does not necessarily lead to perceived coercion. Rather, even when a representative payee and consumer disagree, the findings suggest that it is important to the consumer that the representative payee shows care and consideration for the consumer's concerns and views. Therefore, leverage of disability funds by representative payees will likely have optimal effect if combined with efforts to enhance the sense of self-determination.

Second, representative payees need to be sensitive to the potential stigmatizing effects of consumers' not being in control of their money. In particular, the findings showed that consumers with more education were significantly less open to having money being used as leverage to improve adherence. A possible explanation is that, compared with less educated people with severe mental illness, consumers with a high school or college education may feel relatively more shame when they are reminded of the fact that they do not control their finances.Feelings of empowerment are closely related to issues of stigma (34), and perceiving that one is in control of one's finances may be more significant for an individual who accomplished certain levels of mastery in the past but then lost those skills as a result of mental illness. The findings hint that providers and families should consider the possibility that consumers with higher levels of education may perceive more stigma attached to finance-related issues. Future research should examine how or whether lacking control over one's money relates to stigma among people with psychiatric disabilities.

Discussion of using disability funds to leverage treatment adherence among people with psychiatric disabilities should not overshadow the fact that the primary function of representative payees is to ensure that basic needs are met. Indeed, because the purpose of representative payees is to help consumers, we are concerned that the arrangement may be implemented in countertherapeutic ways. Furthermore, we should reiterate that discretionary money from disability funds is minimal. In fact, SSA benefits scarcely cover affordable housing in many cities. Still, this amount may be very important from a consumer's perspective and may represent the only money a consumer has to purchase some item he or she desires.

These data were collected from patients in one geographic area in North Carolina and may not generalize to all patients with severe mental illness. Another consideration is that even though there was good variability in education level and on current psychotic symptoms, most of the sample had relatively high insight into their illness and reported that they did not abuse substances. Thus we should emphasize that these findings generalize to individuals with schizophrenia who have more understanding of the disorder and who are less likely to abuse substances. Future research would ideally include a wider range of people with schizophrenia and perhaps include a control group of individuals with other disorders for comparison. A final consideration is that the study reported here is based on cross-sectional, retrospective data.

Conclusions

Prospective studies of financial leverage would improve our understanding of consumers' perceptions of these arrangements and the relationship of these perceptions to treatment outcomes (10). If, as our data suggest, the use of money by representative payees to leverage adherence to treatment can be perceived as coercive, developing a client-centered intervention to deliver representative payee services may be warranted. The findings from our study underscore the possibility that for some people with psychiatric disabilities, being reminded that they are not in control of their money may serve to undercut self-esteem and self-efficacy, which can adversely affect outcomes of and adherence to mental health services.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University Medical Center, DUMC 3071, Durham, North Carolina 27710 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Stepwise logistic regression model of factors associated with consumers' agreement that using disability funds to leverage adherence to treatment is helpful (N=104)a

a Model χ2=15.44, df=4, p=.001

1. SSI Annual Statistical Report, 2002. Social Security Online, 2003. Available at www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/ssi_asr/2002/index.htmlGoogle Scholar

2. SSA: Annual Statistical Report on the Social Security Disability Insurance Program. Social Security Online, 2003. Available at www.socialsecurity.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/di_asr/2002/exp_toc.htmlGoogle Scholar

3. Brotman, AW, Muller JJ: The therapist as representative payee. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:167–171, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Satel S: When disability benefits make patients sicker. New England Journal of Medicine 333:794–796, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Shaner A, Eckman TA, Roberts LJ, et al: Disability income, cocaine use, and repeated hospitalization among schizophrenic cocaine abusers—a government-sponsored revolving door? New England Journal of Medicine 333:777–783, 1995Google Scholar

6. A Guide for Representative Payees. Social Security Online, 2001. Available at www.ssa.gov/pubs/10076.htmlGoogle Scholar

7. Rosen MI, Rosenheck R: Substance use and assignment of representative payees. Psychiatric Services 50:95–98, 1999Link, Google Scholar

8. Luchins DJ, Roberst DL, Hanrahan P: Representative payeeship and mental illness: a review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 30:341–353, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Ries RK, Dyck DG: Representative payee practices of community mental health centers in Washington State. Psychiatric Services 48:811–814, 1997Link, Google Scholar

10. Monahan J, Bonnie RJ, Appelbaum PS, et al: Mandated community treatment: beyond outpatient commitment. Psychiatric Services 52:1198–1205, 2001Link, Google Scholar

11. Rosenheck R, Lam J, Randolph F: Impact of representative payees on substance abuse by homeless persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 48:800–806, 1997Link, Google Scholar

12. Stoner MR: Money management services for the homeless mentally ill. Hospital Community Psychiatry 40:751–753, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

13. Ries R, Comtois KA: Managing disability benefits as part of treatment for persons with severe mental illness and co-morbid drug/alcohol disorders: a comparative study of payee and non-payee participants. American Journal of Addiction 6:330–338, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

14. Luchins, DJ, Hanrahan P, Conrad KJ, et al: An agency-based representative payee program and improved community tenure of persons with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 49:1218–1222, 1998Link, Google Scholar

15. Tsemberis S, Gulcur L, Nakae M: Housing First, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. American Journal of Public Health 94:651–656, 2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Tsemberis S, Eisenberg RF: Pathways to housing: supported housing for street-dwelling homeless individuals with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 51:487–493, 2000Link, Google Scholar

17. Shaner A, Roberts LJ, Eckman TA, et al: Monetary reinforcement of abstinence from cocaine among mentally ill patients with cocaine dependence. Psychiatric Services 48:807–814, 1997Link, Google Scholar

18. Frisman LK, Rosenheck R: The relationship of public support payments to substance abuse among homeless veterans with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 48:792–795, 1997Link, Google Scholar

19. Rosenheck R: Disability payments and chemical dependence: conflicting values and uncertain effects. Psychiatric Services 48:789–791, 1997Link, Google Scholar

20. Elbogen EB, Swanson JW, Swartz MS: Effects of legal mechanisms on perceived coercion and treatment adherence among persons with severe mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 191:629–637, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Elbogen EB, Swanson JW, Swartz MS: Psychiatric disability, the use of financial leverage, and perceived coercion in mental health services. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health 2:119–127, 2003Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Rosenheck R, Neale MS: Therapeutic limit setting and six-month outcomes in a Veterans Affairs assertive community treatment program. Psychiatric Services 55:139–144, 2004Link, Google Scholar

23. Dixon L, Turner J, Kraus N, et al: Case managers' and clients' perspectives on a representative payee program. Psychiatric Services 60:781–786, 1999Link, Google Scholar

24. Pfeiffer EA: Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 23:433–441, 1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Cuffel BJ, Fischer EP, Owen RR Jr, et al: An instrument for the measurement of care for schizophrenia: issues in development and implementations. Evaluation and the Health Professions 20:6–108, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

26. McEvoy JP, Apperson LJ, Appelbaum PS, et al: Insight in schizophrenia: its relationship to acute psychopathology. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 177:43–47, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Fenton WS, Blyler CR, Heinssen RK: Determinants of medication compliance in schizophrenia: empirical and clinical findings. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:637–651, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Lidz CW, Hoge SK, Gardner W, et al: Perceived coercion in mental hospital admission: pressures and process. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:1034–1039, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Lind E, Kanfer R, Early P: Voice, control, and procedural justice: instrumental and noninstrumental concerns in fairness judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 59:952–959, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Lind E, Tyler T: The Social Psychology of Procedural Justice. New York, Plenum Press, 1988Google Scholar

31. Bennett NS, Lidz CW, Monahan J, et al: Inclusion, motivation, and good faith: the morality of coercion in mental hospital admission. Behavioral Science and Law 11:295–306, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Kjellin L, Nilstun T: Medical and social paternalism: regulation of and attitudes towards compulsory psychiatric care. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 88:415–419, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Kjellin L, Andersson K, Candefjord I, et al: Ethical benefits and costs of coercion in short-term inpatient psychiatric care. Psychiatric Services 48:1567–1570, 1997Link, Google Scholar

34. Corrigan PW: Empowerment and serious mental illness: treatment partnerships and community opportunities. Psychiatric Quarterly 73:217–228, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar