Mental Health Issues Among Female Clients of Domestic Violence Programs in North Carolina

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study estimated the prevalence of mental health problems among clients of domestic violence programs in North Carolina, determined whether domestic violence program staff members routinely screen clients for mental health problems, described how domestic violence programs respond to clients who have mental health problems, and ascertained whether domestic violence program staff members and volunteers have been trained in mental health-related issues. METHODS: A survey was mailed to all known domestic violence programs in North Carolina. RESULTS: A total of 71 of the 84 known programs responded to the survey (85 percent response rate). A majority of programs estimated that at least 25 percent of their clients had mental health problems (61 percent) and stated that they routinely asked their clients about mental health issues (72 percent). More than half the programs (54 percent) reported that less than 25 percent of their staff members and volunteers had formal training on mental health issues. An even smaller percentage of programs (23 percent) reported that they had a memorandum of agreement with a local mental health center. CONCLUSIONS: The substantial percentage of domestic violence clients with concurrent mental health needs and the limited mental health services that are currently available have important implications for domestic violence and mental health service delivery.

Female lifetime prevalence estimates for domestic violence range from 20 to 40 percent (1,2,3,4). Domestic violence has a negative impact on health, with both acute and chronic sequelae. Increased health care use, mental illness, substance abuse, pregnancy complications, and numerous chronic physical conditions have been associated with domestic violence (5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12).

Previous research has demonstrated a particularly strong association between domestic violence and two mental illnesses: depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (13,14,15,16,17,18). Among members of a New Zealand birth cohort, more than half the women who were victimized by violence suffered from a psychiatric disorder, and nearly two-thirds of the women who were victimized by severe partner violence had one or more psychiatric disorders (16). Gleason (17) found high rates of mental health problems among abused women who received services from a domestic violence agency; some of these women resided at the shelter, and others lived in the community.

Similarly, in her meta-analysis of 18 studies on depression, Golding (14) reported that women who experienced domestic violence were 3.8 times as likely as nonabused women to have depression. A meta-analysis of 11 studies of posttraumatic stress disorder reported a weighted mean prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder of 63.8 percent among battered women; furthermore, women who experienced domestic violence were 3.7 times as likely as nonabused women to develop posttraumatic stress disorder (18).

The etiology of mental illness among battered women is unclear, as the bulk of previous research cannot establish a temporal sequence and the relationship is likely to be bidirectional (12). The documented association between domestic violence and women's mental health suggests that a high proportion of battered women who seek help for domestic violence will have concurrent mental health needs. Thus it is important that domestic violence victims who have mental health problems receive both appropriate domestic violence services and mental health treatment.

Women who are experiencing domestic violence seek help from a variety of sources, including domestic violence programs. These programs are often victims' "portal of entry," linking women to other resources and services in the community (19,20). Domestic violence programs are typically local nonprofit agencies that have volunteers and paid staff members and that offer a range of services to domestic violence victims and the community. These services include emergency shelter, access to a 24-hour crisis hotline, in-person and group counseling, legal and medical advocacy, community education, and outreach activities (20).

Despite the documented links between domestic violence and mental illness and the critical role of domestic violence service programs in addressing the multiple needs of battered women, there is a dearth of published information about the prevalence of mental illness among women who are seeking services from domestic violence programs. There is also a lack of published information about how such programs seek to meet the mental health needs of their clients. To address this gap, we present data from a statewide survey of domestic violence programs. We estimated how common mental health problems are among clients of domestic violence programs in North Carolina, determined whether the staff of domestic violence programs routinely screen clients for mental health problems, described how domestic violence programs in North Carolina respond to clients who have mental health problems, and ascertained whether staff members and volunteers at domestic violence programs have been trained in mental health-related issues.

Methods

Survey development

We convened a working group of researchers, practitioners, and advocates to design a self-administered survey that would be mailed to all known domestic violence programs in North Carolina. The survey was designed to assess the types of services provided, challenges faced, and resources and training that were desired to meet clients' needs, including needs related to mental illness, disabilities, substance abuse, and language and culture (21,22).

The section of the survey that was related to mental illness asked for estimates of the proportion of clients with mental health problems, whether clients are screened for mental health problems, whether policies and practices exist that address the needs of clients with severe mental health problems, and for estimates of the percentage of staff members and volunteers with training in mental health. A copy of the survey is available from the first author. In addition, we included two open-ended questions about the challenges encountered and the strategies used by the programs while serving clients with mental health problems. We also used information from the North Carolina State Data Center to create a variable that indicated whether the domestic violence program came from a county that was classified as a nonurban county, which included rural and intermediate counties, or as an urban county (22).

We pretested the survey with staff members from the North Carolina Coalition Against Domestic Violence and revised the instrument according to their suggestions. The full working group reviewed and approved the final questionnaire. The institutional review board for the committee on the protection of the rights of human subjects from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine reviewed the research protocol and survey and determined that it met exemption criteria.

Survey implementation

We compiled a list of domestic violence service providers in North Carolina from the membership lists of the North Carolina Coalition Against Domestic Violence, the programs that were receiving state-appropriated funding from the North Carolina Council for Women, and additional programs that were known to members of the working group. We identified 85 domestic violence programs and sent them the survey, which was accompanied by a cover letter that included logos from the North Carolina Coalition Against Domestic Violence, the North Carolina Domestic Violence Commission, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Representatives from each of these institutions signed the letter. To maintain confidentiality, we assigned an identification number to each domestic violence agency, and no identifying information was included on the survey itself. Only the researchers knew which programs responded.

We mailed the surveys in December 2000 to all the programs, followed by a postcard reminder in early January 2001 and a second survey mailing at the end of January 2001 to programs that had not responded. At the end of March 2001 trained interviewers from the University of North Carolina Injury Prevention Research Center contacted the programs that had not responded and attempted to administer the survey over the telephone. Of the 85 surveys that were mailed, 64 were completed and returned by mail, seven were completed by telephone interview, 12 were never returned, and one was returned without being opened because the program had closed, resulting in a response rate of 85 percent (71 of 84 operating programs).

Data analysis

All quantitative data were analyzed with the Stata 7.0 statistical package (23). We used descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages for categorical and ordinal data, and means and standard deviations for continuous variables to describe the participating programs' client characteristics and approaches to mental health issues. Bivariate analyses were performed with Mantel-Haenzel chi square tests (24) or, when the numbers were small, Fisher's exact tests (24,25). We analyzed the qualitative information from the open-ended questions by reading the participants' responses and then abstracting the overarching themes that emerged in response to those questions (26).

Results

Services provided

Most of the 71 domestic violence programs that responded to our survey reported that they provided a wide variety of services, although the size and scope of these services varied considerably among programs. The most common types of services that were provided included court advocacy (70 programs, or 99 percent), crisis intervention and domestic violence counseling (67 programs, or 94 percent), telephone hotlines (66 programs, or 93 percent), shelter (62 programs, or 87 percent), transportation (57 programs, or 81 percent), and counseling for children who have witnessed domestic violence (54 programs, or 76 percent). In addition, 33 programs (47 percent) provided a variety of other types of services, such as support groups, parenting groups, job or life skills classes, professional training and education classes, batterer treatment, case management, medical care, child care, and emergency financial assistance.

The annual number of clients who were served by North Carolina domestic violence programs varied greatly. For example, the estimated number of hotline calls that were received annually ranged from 0 to 6,000, with a mean±SD of 792±1,096; the estimated number of women who were counseled each year ranged from 0 to 3,000, with a mean of 551±677; and the estimated annual number of women who used shelter services ranged from 0 to 815, with a mean of 188±168.

Mental health needs

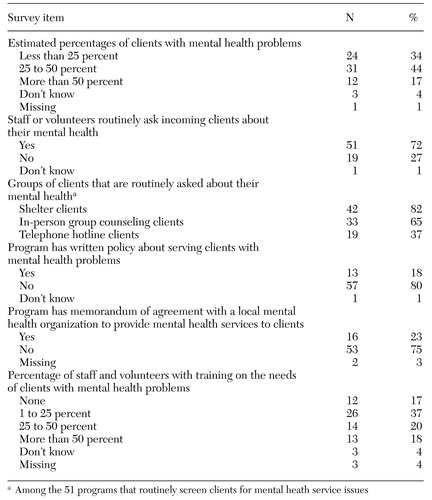

As shown in Table 1, respondents from the programs perceived that a substantial proportion of women who are seeking help from domestic violence programs in North Carolina have concurrent mental health problems. Nearly two-thirds of the domestic violence programs (43 programs, or 61 percent) estimated that at least 25 percent of their clients had mental health problems; 12 programs (17 percent) estimated that more than half of their clients had mental health problems. A program's urban or nonurban status did not appear to be statistically related to the reported percentages of clients with mental health problems.

Almost three-quarters of the programs (51 programs, or 72 percent) employed some type of routine screening for mental health problems. However, among the programs that reported routinely screening clients, the screening measures were not universally applied to all clients. Respondents from the programs stated that clients who used shelter services were the most common group of clients to receive routine screening (42 programs, or 82 percent of programs that screen clients), followed by clients who received in-person group counseling (33 programs, or 65 percent) and clients calling the telephone hotline (19 programs, or 37 percent). The presence of routine screening was not associated with the proportion of clients who were reported to have mental health problems.

Despite the belief of domestic violence program staff members that a considerable proportion of their clients had mental health problems, only 13 responding programs (18 percent) had a written policy about working with clients with mental health needs. Similarly, only 16 programs (23 percent) stated that they had memoranda of agreement with local mental health agencies to provide treatment to their clients. Of the 16 programs that reported having a memorandum of agreement, only five (31 percent) reported that clients had the option of receiving mental health services on-site at the domestic violence agency. The remaining 11 programs (69 percent) referred clients to off-site mental health services.

When the 62 programs that provided shelter services were asked what their staff members and volunteers would do "if a woman who has severe mental health problems (that is, the client is suicidal or has schizophrenia) comes to your program needing shelter," only 6 respondents (10 percent) reported that they would refuse to complete intake with the client. The most common response was to refer the client to the local mental health center (54 programs, or 87 percent). However, it was not clear whether these referred clients would also be allowed to stay at the shelter.

In terms of training on mental health issues, more than a third of the programs (38 programs, or 54 percent) reported that less than 25 percent of their staff and volunteers had formal training on mental health issues. Again, the percentage of clients with mental health problems who were seen by a program was not significantly related to the percentage of formally trained staff members and volunteers. Finally, 69 domestic violence programs (97 percent) stated that they would like mental health training routinely available to their staff and volunteers.

Challenges and successful strategies

Programs were asked two open-ended questions about the challenges that were posed by clients who have mental health problems and the strategies that programs felt were helpful in addressing the needs of those clients. The challenges that were cited by program staff fell into four somewhat overlapping categories: those related to shelter, medication, the complexity of treatment required for clients with mental health problems, and the lack of community mental health resources.

In terms of shelter-related challenges, respondents noted safety concerns for women who have mental health problems. One respondent wrote, "Women in the midst of mental health crises may become threatening to others who are there to feel safe." Another shelter-related challenge that was noted by domestic violence program staff members was the lack of appropriate residential options for battered women who have mental health problems.

Respondents also cited challenges that were related to the medication needs of battered women who have mental health problems, such as the prohibitive cost of needed medication, the lengthy process of assisting clients in applying for Medicaid, and clients nonadherence to prescribed medications.

The complexity of treatment that is needed for battered women who have mental health problems was also listed as a challenge. Respondents noted that when their clients' mental health needs were unmet, the program's services that were related to domestic violence were less effective. Several mentioned that clients who have mental health problems were more likely to return to their abusers and were more susceptible to controlling tactics.

Finally, respondents cited the dearth of mental health services in their communities, noting the lack of inpatient treatment programs, lengthy waits for appointments with mental health providers, and clients inappropriately referred to the domestic violence agency because alternative services were not available.

Successful strategies that were cited by programs involved collaboration with local mental health providers. These strategies included either formal or informal collaborations as well as arranging for mental health services to be provided in-house, that is, within the domestic violence program. Having a memorandum of agreement with mental health providers was highly recommended by the few programs that had them. Some respondents felt that the ability of clients of domestic violence programs to simultaneously receive mental health services and domestic violence services in-house was crucial.

Discussion and conclusions

Mental health problems appear to be common among clients who are seeking services from domestic violence programs in North Carolina. Serving women with mental health problems presents formidable challenges to the delivery of effective domestic violence-related interventions. Most programs routinely screen for mental illness—at least among women who are seeking shelter or in-person counseling. However, despite the high prevalence of mental health problems among the programs' clients, a majority of programs reported that they have few staff members and volunteers who have had formal training in mental health issues, and few programs reported that they have memoranda of agreement with their local mental health centers.

The findings of our study must be viewed in light of its limitations. Our results are descriptive, with limited ability to assess associations. The prevalence of domestic violence program clients who have mental health problems is based on estimates by program staff members, not by clinical diagnoses or systematic measurement. Additionally, we have no information about the different types of mental health problems that these clients are experiencing. Although the high response rate (71 programs, or 85 percent) suggests that the study results described almost all the community-based domestic violence programs in North Carolina, the data may not reflect the experiences and situations that are faced by hospital-based domestic violence programs or by programs in other states.

Despite these limitations, the results of this research suggest several strategies for addressing the needs of battered women who have mental illness. The programs' recognition of a high prevalence of mental illness among their clients indicates a call for protocols for screening, referring, and treating clients with mental health needs. These protocols might outline steps for obtaining medications, inpatient care in the case of mental health crisis, and the necessary follow-up required for therapy that extends beyond shelter stays. Ideally, given the high prevalence of mental illness among clients of domestic violence programs, these programs would have on-site resources and services for mental health treatment to efficiently meet both the safety and treatment needs of clients. In addition, the respondents identified the need for further training about mental health issues for domestic violence staff members and volunteers.

Programs must have sufficient resources to enact the above recommendations and maximize their ability to help victims of domestic violence with mental health problems. Many domestic violence agencies are administered by a handful of staff members on a shoestring budget. Effectively addressing the needs of all victims of domestic violence will require that communities support local domestic violence programs by investing the time and resources needed.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded in part by grant R49-CCR-402-444 from the National Center of Injury Prevention and Control to the University of North Carolina Injury Prevention Research Center and by the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program. Several members of the violence working group at the University of North Carolina Injury Prevention Research Center provided their valuable time and expertise in designing and executing this project: Michele Decker, M.P.H., Pam Dickens, B.A., Patty Neal Dorian, M.A., L.P.C., Jeanne Givens, M.S.S.W., Alison Hilton, M.P.H., Jenny Koenig, M.P.H., Lauren McDevitt, M.S., Beth Posner, J.D., Marcia Roth, M.P.H., Donna Scandlin, M.Ed., and Deborah M. Weissman, J.D.

Dr. Moracco is affiliated with the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation, 1516 East Franklin Street, Suite 200, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27514 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Martin is with the department of maternal and child health, Ms. Dulli is with the department of health behavior and health education, and Dr. Moracco, Dr. Martin, and Ms. Dulli are with the Injury Prevention Research Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Brown is with the Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, North Carolina. Dr. Chang is with the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Pittsburgh. Ms. Loucks-Sorrell is with the North Carolina Coalition Against Domestic Violence in Durham. Ms. Starsoneck and Ms. Turner were with the North Carolina Council for Women and Domestic Violence Commission in Raleigh at the time this research was conducted. Ms. Bou-Saada is with the injury and violence prevention branch of the division of public health of the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services in Raleigh.

|

Table 1. Results from a statewide survey about the mental health of women in domestic violence programs in North Carolina (N=71)

1. Tjaden P, Thoennes N: Extent, Nature, and Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence: Findings From the National Violence Against Women Survey. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice, pub no NCJ 181867, 2000Google Scholar

2. Rennison CM, Welchans S: Intimate Partner Violence. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, pub no NCJ 178247, 2000Google Scholar

3. Rhodes KV, Lauderdale DS, He T, et al: "Between me and the computer": increased detection of intimate partner violence using a computer questionnaire. Annals of Emergency Medicine 40:476–484, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Coker AL, Smith PH, McKeown RE, et al: Frequency and correlates of intimate partner violence by type: physical, sexual, and psychological battering. American Journal of Public Health 90:553–559, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Campbell JC: Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet 359:1331–1336, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Drossman DA, Talley NJ, Lesserman J, et al: Sexual and physical abuse and gastrointestinal illness. Annals of Internal Medicine 123:782–794, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Coker AL, Smith PH, Bethea L, et al: Physical health consequences of physical and psychological intimate partner violence. Archives of Family Medicine 9:451–457, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Koss MP, Koss M, Woodruff W: Deleterious effects of criminal victimization on women's health and medical utilization. Archives of Internal Medicine 151:342–357, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Hathaway JE, Mucci LA, Silverman JG, et al: Health status and health care use of Massachusetts women reporting partner abuse. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 19:302–307, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Miller BA: Partner violence experiences and women's drug use: exploring the connections, in Drug Addition Research and the Health of Women. Edited by Wetherington CL, Roman AB. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Rockville, Md, 1998Google Scholar

11. Martin SL, Kilgallen B, Dee D, et al: Women in a prenatal care substance abuse treatment program: links between domestic violence and mental health. Maternal and Child Health Journal 2:85–94, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Frank JB, Rodowski MF: Review of psychological issues in victims of domestic violence seen in emergency setting. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America 17:657–677, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Scholle SH, Rost KM, Golding JM: Physical abuse among depressed women. Journal of General Internal Medicine 13:607–613, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Golding JM: Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: a meta-analysis. Journal of Family Violence 14:99–132, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Danielson KK, Moffitt TE, Avshalom C, et al: Comorbidity between abuse of an adult and DSM-III-R mental disorders: evidence from an epidemiological study. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:131–133, 1998Link, Google Scholar

16. Roberts GL, Lawrence JM, Williams GM, et al: The impact of domestic violence on women's mental health. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 22:796–801, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Gleason WJ: Mental disorders in battered women: an empirical study. Violence and Victims 8:53–68, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

18. Jones L, Hughes M, Unterstaller U: Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in victims of domestic violence: a review of the research. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse 2:99–119, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Riger S, Bennett L, Wasco SM, et al: Evaluating Services for Survivors of Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 2002Google Scholar

20. Saathoff AJ, Stoffel EA: Community-based domestic violence services. Future of Children 9:97–110, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Chang JC, Martin SL, Moracco KE, et al: Helping women with disabilities and domestic violence: strategies, limitations, and challenges of domestic violence programs and services. Journal of Women's Health 12:699–708, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. North Carolina Census Data Lookup. North Carolina State Data Center. Available at: http://census.osbm.state.nc.us/lookupGoogle Scholar

23. Hamilton LC: Statistics with STATA. Pacific Grove, Calif, Duxbury, 2002Google Scholar

24. Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Morgenstern H: Epidemiologic Research: Principles and Quantitative Methods. Belmont, Calif, Wadsworth, 1982Google Scholar

25. Kendall M, Stuart A: The Advanced Theory of Statistics: Vol 2. New York, Macmillan Publishing, 1979Google Scholar

26. Silverman D: Interpreting Qualitative Data: Methods for Analyzing Talk, Text, and Interaction, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage Publications, 2001Google Scholar