Comorbidity Between Abuse of an Adult and DSM-III-R Mental Disorders: Evidence From an Epidemiological Study

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to report the prevalence, risk, and implications of comorbidity between partner violence and psychiatric disorders. METHOD: Data were obtained from a representative birth cohort of 941 young adults through use of the Conflict Tactics Scales and Diagnostic Interview Schedule. RESULTS: Half of those involved in partner violence had a psychiatric disorder; one-third of those with a psychiatric disorder were involved in partner violence. Individuals involved in severe partner violence had elevated rates of a wide spectrum of disorders. CONCLUSIONS: The findings support the importance of mental health clinicians screening for partner violence and treating victims and perpetrators before injury occurs. (Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:131–133)

Studies of partner violence reveal that 35%–50% of young adults are involved in some level of physical abuse (1). Accordingly, the mental health field has made partner violence a focus of clinical attention with its creation of the category physical abuse of adult in DSM-IV. Acknowledging that partner violence may represent a clinical condition raises the possibility that abusive relationships may co-occur with other clinical disorders. This study aimed to estimate the base rates of psychiatric disorders among women who are victims and men who are perpetrators of partner violence because these persons are most frequently treated in mental health facilities.

Previous studies found that women who are victims of partner violence have elevated rates of depression, anxiety, personality disorders, schizophrenia, and drug and alcohol abuse and that men who are perpetrators of partner violence have elevated rates of depression, personality disorders, and drug and alcohol abuse (2–7). However, these studies relied on samples from shelters (2, 4), medical settings (3), treatment programs (5–7), and correctional facilities (5). Such samples are biased by factors associated with treatment seeking or adjudication. Therefore, epidemiological studies such as this one are needed to identify rates and patterns of comorbidity in the age segment of the general population that is at greatest risk for partner violence (8). Such knowledge can inform theory about relations between these conditions and can inform clinicians who treat partner violence about what other disorders they should assess and treat.

METHOD

Participants were members of the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study, a representative birth cohort (N=1,037; 52% men, 48% women) studied since birth in 1972–1973. We report data gathered when the subjects were age 21, when 92% of the living study members provided data about their intimate relationships and mental health. The sample, design, and data are described extensively elsewhere (9–12). All subjects gave written informed consent.

Partner violence in the previous 12 months was measured through use of the Conflict Tactics Scales (13). We examined any physical violence, which referred to any of three minor or six severe violent behaviors in the Conflict Tactics Scales (minor: throw object at partner; push, grab, or shove partner; slap partner; severe: kick, bite, or hit with fist; hit with object; beat up; choke or strangle; threaten with a knife or gun; use a knife or gun), and severe physical violence, which referred to any of the six severe violent behaviors in the Conflict Tactics Scales.

The Diagnostic Interview Schedule (14) was used to obtain diagnoses of 15 DSM-III-R disorders in the previous 12 months: 1) six anxiety disorders: generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, and simple phobia; 2) three mood disorders: major depressive episode, manic episode, and dysthymia; 3) two eating disorders: anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa; 4) two substance use disorders: alcohol dependence and marijuana dependence; 5) antisocial personality disorder; and 6) “nonaffective psychosis,” which consisted of the positive symptoms of schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder. Rates of partner violence (10) and mental disorders (11) in the Dunedin study are comparable to national rates for young adults in the United States.

RESULTS

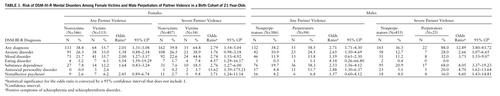

Table 1 shows the prevalence and risk of psychiatric disorders among female victims and male perpetrators of any and severe partner violence. (Tables reporting findings for each of the 15 specific disorders are available from Dr. Moffitt on request.) Over half of the women victimized by violence suffered a DSM-III-R disorder; they had significantly elevated rates of mood and eating disorders. Nearly two-thirds of the women victimized by severe partner violence met criteria for one or more disorders and had significantly elevated rates of mood, eating, and substance use disorders, as well as antisocial personality disorder and symptoms of schizophrenia. Over half of the male perpetrators of partner violence met criteria for some type of disorder and had significantly elevated rates of anxiety disorder, substance use, and antisocial personality disorder. Virtually all male perpetrators of severe partner violence met criteria for one or more of a wide spectrum of psychiatric disorders.

DISCUSSION

This study provides evidence that abusive relationships co-occur with other clinical disorders. Women who were victims and men who were perpetrators of mild forms of partner violence had significantly higher rates of disorders that mirror gender differences in the general population: greater depression and eating disorder among women and greater substance dependence and antisocial personalities among men. In contrast, both women and men involved in severe partner violence showed elevated rates of a wider spectrum of psychopathology. The most severe forms of partner violence are likely to be experienced and perpetrated by individuals with poor mental health. This study probably underestimates the true extent of comorbidity because not all DSM disorders were assessed.

These epidemiological findings about comorbidity between partner abuse and psychiatric disorder underscore the need to screen for partner violence in mental health clinics. Recent discussions have focused on how general practitioners can screen for partner violence in medical facilities (15). The advantage of screening for partner violence in mental health facilities, in addition to medical facilities, is that medical practitioners see only the victims, generally after an injury, whereas mental health clinicians may see both victims and perpetrators, in time to prevent injury. Findings about comorbidity may also inform treatment programs for partner abuse. Some cases of partner violence could be resistant to treatment because comorbid psychiatric disorders complicate the clinical picture. For example, among male perpetrators of severe violence in our study, 48% met criteria for two or more psychiatric disorders. In attempting to change a batterer's behavior, health professionals may also have to treat disorders such as substance use and paranoid delusions for behavioral change to occur. The present findings suggest a need to reconsider institutional practices that separate services for victims and perpetrators of partner violence from services for persons suffering psychiatric disorders.

|

Received Nov. 12, 1996; revision received April 15, 1997; accepted May 12, 1997. From the University of Wisconsin, Madison; Institute of Psychiatry, University of London; and University of Otago Medical School, Dunedin, New Zealand. Address reprint requests to Dr. Moffitt, Institute of Psychiatry, De Crespigny Park, London SE5 8AF, England; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by award 94-IJ-CX-0041 from the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice; NIMH grants MH-45070 from the Violence and Traumatic Stress Branch (to Dr. Moffitt) and MH-49414 from the Personality and Social Processes Branch (to Dr. Caspi); the William T. Grant Foundation; and the William Freeman Vilas Trust at the University of Wisconsin. The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Research Unit is supported by the New Zealand Health Research Council. Points of view in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Department of Justice. The authors thank the Dunedin unit investigators and staff and the study members and their families.

1. Fagan J, Browne A: Violence between spouses and intimates: physical aggression between women and men in intimate relationships, in Understanding and Preventing Violence, vol 3: Social Influences. Edited by Reiss AJ Jr, Roth JA. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1994, pp 115–292Google Scholar

2. Gleason UJ: Mental disorders in battered women: an empirical study. Violence Vict 1992; 8:53–68Google Scholar

3. Rounsaville BJ: Theories in marital violence: evidence from a study of battered women. Victimology 1978; 3:11–31Google Scholar

4. West CG, Fernandez A, Hillard JR, Schoof M, Parks J: Psychiatric disorders of abused women at a shelter. Psychiatr Q 1990; 61:295–301Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Miller BA: The interrelationships between alcohol and drugs and family violence. NIDA Res Monogr 1990; 103:177–207Medline, Google Scholar

6. Dinwiddie SH: Psychiatric disorders among wife batterers. Compr Psychiatry 1992; 33:411–416Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Barnett OW, Fagan RW: Alcohol use in male spouse abusers and their female partners. J Family Violence 1993; 8:1–25Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Bureau of Justice Statistics: Violence Against Women: Estimates From the Redesigned Survey. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, 1995Google Scholar

9. Silva PA: The Dunedin multidisciplinary health and development study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 1990; 4:96–127Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Newman DL, Silva PA: Behavioral observations at age 3 years predict adult psychiatric disorders: longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:1033–1039Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Magdol L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Newman DL, Fagan J, Silva PA: Gender differences in partner violence in a birth-cohort of 21-year-olds: bridging the gap between clinical and epidemiological approaches. J Consult Clin Psychol 1997; 65:68–72Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Newman DL, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Magdol L, Silva PA, Stanton W: Psychiatric disorder in a birth cohort of young adults: prevalence, comorbidity, clinical significance, and new case incidence from age 11 to 21. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996; 64:552–562Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Straus MA: Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: the Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales, in Physical Violence in American Families: Risk Factors and Adaptations to Violence in 8,145 Families. Edited by Straus MA, Gelles RJ. New Brunswick, NJ, Transaction, 1990, pp 29–45Google Scholar

14. Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS: The National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:381–389Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Alpert EJ: Violence in intimate relationships and the practicing internist: new “disease” or new agenda? Ann Intern Med 1995; 123:774–781Google Scholar