Disparities in the Adequacy of Depression Treatment in the United States

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: There is evidence of disparities in depression treatment by factors such as age, race or ethnicity, and type of insurance. The purpose of this study was to assess whether observed disparities in treatment are due to differences in rates of treatment initiation or to differences in the quality of treatment once treatment has been initiated. METHODS: Logistic regression models using data from the 2000 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey were estimated to assess the role of age, race or ethnicity, and type of insurance on rates of initiation of depression treatment for persons with self-reported depression and on rates of adequate treatment for those receiving treatment. RESULTS: African Americans and Latinos were significantly less likely to fill an antidepressant prescription than Caucasians. However, among patients who filled at least one prescription for an antidepressant, there were no racial or ethnic disparities in the probability of receiving an adequate trial of antidepressant medication. African Americans were more likely than Latinos and Caucasians to receive an adequate course of psychotherapy. Persons who did not have insurance coverage were less likely to initiate any depression treatment compared with those who did have insurance. However, if treatment was initiated, no difference in the probability of receiving adequate treatment was observed. Elderly persons were less likely to receive an adequate course of psychotherapy or counseling compared with younger persons. CONCLUSIONS: Disparities in depression treatment appear to be due mainly to differences in rates of initiation of depression treatment, given that rates of adequate care generally did not differ once treatment was initiated.

Depression is common, is costly, and has a significant impact on functioning and quality of life (1,2,3). Effective treatments for depression exist, and national treatment guidelines for major depression have been developed (4,5,6). Nevertheless, it is common for persons with depression to receive no treatment or to be undertreated (3,7,8,9,10,11), and the quality of depression care in the United States is low, with rates of adequate treatment ranging from 7 percent to 30 percent (3,7,10,12,13).

African Americans, elderly persons, and Medicaid enrollees are particularly vulnerable to undertreatment of depression (10,14,15,16,17,18,19). Depression treatment rates for African Americans have been found to be between one-half and one-third of those for Caucasians (10,20,21,22), and individuals who do receive treatment are substantially less likely to receive guideline-concordant care (12). Studies show that elderly persons are much less likely to receive a diagnosis of depression, and as many as half to three-quarters of elderly persons receive no antidepressant treatment for their depressive symptoms; of those who do receive antidepressants, less than one-third receive adequate treatment (10,18,23,24). Elderly patients also have lower rates of use of psychotherapy than nonelderly patients (22). Medicaid patients have been found to be less likely to receive selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and less likely to receive psychotherapy, and they have lower rates of continuous therapy compared with patients who are privately insured (16,17).

Although recent studies have investigated quality of care for depression by age, race, and type of insurance, many studies have not clarified whether low rates of adequate care for subpopulations stem from low rates of initiation of treatment or from low quality of care once treatment has been initiated (3,7,10). Knowing the answer to this question will help policy makers and clinicians design appropriate health policy and other interventions with the best chance of improving depression care.

The study reported here used nationally representative data to compare rates of initiation of depression treatment, and, among those receiving treatment, rates of adequate depression treatment by race or ethnicity, age, and type of insurance. Rates of adequate treatment for persons who used psychotherapy or counseling services and those who used antidepressants were assessed separately.

Methods

Data

We used data from the 2000 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), a nationally representative annual survey sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The MEPS uses an overlapping panel design that collects data for individuals over a two-year period through a baseline interview and five follow-up interviews and can be used for cross-sectional or longitudinal analysis (25). The MEPS Household Component (HC) collects detailed information about health care use and expenditures, health status, and health insurance coverage as well as demographic information and is designed to produce annual estimates of these measures. The MEPS HC sample is drawn from a subsample of households included in the previous year's National Health Interview Survey. The 2000 MEPS HC data are from baseline and follow-up interviews with 25,096 individuals. The data in the MEPS 2000 HC are described in detail at www.meps.ahrq.gov.

Individuals with depression

Individuals with depression were identified by using the MEPS HC medical conditions file. This file contains an observation for each self-reported medical condition that the individual experiences during the year. During each interview, respondents were asked about medical conditions they experienced during the four or five months since the previous interview. Thus all conditions are self-reported by respondents. Self-reported conditions were mapped onto three-digit ICD-9 codes by AHRQ. We classified conditions with ICD-9 codes of 296 or 311 as depression. Although the code 296 can also include bipolar disorder, more than 90 percent of individuals identified through these codes had a code of 311, corresponding to unspecified depression. In this study, the term "depression" is used to identify these individuals. On the basis of this method, 1,347 individuals were identified as having depression.

Antidepressant treatment

Antidepressant treatment was identified by using the prescribed medicines event file of the 2000 MEPS HC, which contains 182,677 prescribed medicine records. Each record represents one household-reported prescribed medicine purchased or obtained during 2000. Antidepressant medications were identified by drug name. The drugs classified as antidepressants were amitriptyline, amoxapine, bupropion, citalopram, clomipramine, desipramine, doxepin, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, imipramine, isocarboxazid, maprotiline, mirtazapine, nefazodone, nortriptyline, paroxetine, phenelzine, protriptyline, sertraline, tranylcypromine, trazodone, trimipramine, and venlafaxine.

We calculated the daily dosage for each antidepressant prescription by using the pill dosage and the number of pills in the prescription. In our analysis, it was assumed that each antidepressant prescription was for a 30-day supply. After inspection of all prescription records by a psychiatrist (the second author), we decided to assume that if fewer than 30 pills were prescribed, the number of days supplied by the prescription equaled the number of pills supplied by the medication. Of the 8,944 prescriptions for antidepressants, 1,513 (17 percent) were for fewer than 30 pills. The daily dosages were then compared with the minimum adequate daily dosage developed by Weilburg and colleagues (11) by using consensus of expert opinion and manufacturers' guidelines (11). Because the purpose of this study was not to assess absolute rates of adequate treatment but to investigate differences in rates of treatment between groups, this method would not have introduced bias into the analysis if the differences in days supplied were distributed equally across groups.

Psychotherapy or mental health counseling visits

Psychotherapy or mental health counseling visits were identified by using the 2000 MEPS outpatient visit file (N=10,937) and the 2000 MEPS office-based medical provider visits file (N=99,939). These files contain one observation for each self-reported visit to a hospital-based outpatient clinic or office-based medical provider during 2000. For each visit, the respondent was asked which category best described the care provided during the visit. One possible category of response was "psychotherapy or mental health counseling."

Adequate depression care

Adequate depression treatment over a one-year period was defined as receipt of at least four antidepressant prescriptions at the minimum adequate daily dosage or at least eight outpatient or office-based psychotherapy or counseling visits. This definition was based on evidence-based treatment guidelines (5,26) and is similar to that used by Kessler and colleagues (3) in their analysis of depression care that used data from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication.

Health and functional status

We adjusted for self-perceived health and mental health status and for functional limitations by using responses from the MEPS HC. Respondents rated overall health as excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor at three points during the calendar year. Respondents rated mental health by using the same categories. Respondents were also asked about functional limitations by using the Activities of Daily Living scale (27) and the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scale (28). A dummy variable was coded 1 if the individual had at least one limitation on the Activities of Daily Living scale and was coded 0 otherwise. A dummy variable was coded in the same way for the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scale. All health and functional status variables used measures collected during the first interview of the calendar year.

Sociodemographic measures

The analysis examined differences in adequate care by race or ethnicity, age, sex, insurance type, income, education, and marital status. Race or ethnicity consisted of four mutually exclusive groups: Caucasian, African American, Latino, and other. Any respondent who identified him- or herself as Latino was categorized as Latino, regardless of race. Age was coded as less than 18 years, 18 to 34 years, 35 to 64 years, and 65 years and over. Insurance type was categorized as any private insurance, Medicaid, Medicare, both Medicaid and Medicare, and uninsured. Income was measured as a percentage of the poverty level and was assigned to five categories: poor (less than 100 percent of the federal poverty level), near poor (100 to 124 percent), low income (125 to 199 percent), middle income (200 to 399 percent), and high income (more than 399 percent). Education was included as a dichotomous variable, coded 1 if the individual had a college education or above and coded 0 otherwise. Marital status was classified as married, widowed, divorced or separated, and never married.

Statistical analysis

Logistic regression was used, because all dependent variables were dichotomous. The first regression examined receipt of at least one antidepressant prescription among persons with depression. The second regression examined the probability of receipt of an adequate course of antidepressants among persons with depression who had received at least one prescription for an antidepressant. The third regression assessed the probability of receipt of psychotherapy or mental health counseling among persons with depression. The fourth regression assessed the probability of receipt of an adequate course of psychotherapy among persons with depression who made at least one psychotherapy visit. To investigate whether persons who were receiving combination therapy were more likely to receive adequate treatment than those who were receiving antidepressants only or psychotherapy or counseling only, the two models that assessed whether adequate treatment was provided included independent variables indicating whether the person received both antidepressants and psychotherapy during the year. Finally, to help assess whether the type of treatment initiated (antidepressants or psychotherapy or counseling) was associated with higher rates of adequate care, a fifth regression examined the probability of receiving any form of adequate care given that the individual was depressed and used either antidepressants or psychotherapy or counseling at any point during the year, with indicator variables included in the model to indicate the type of treatment initiated. Models were estimated by using the survey procedures of Stata statistical software, using weights to account for the complex sampling strategy and to produce estimates that were nationally representative (29).

Results

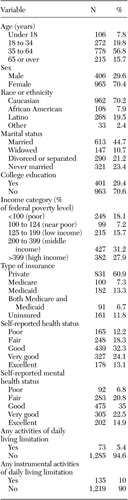

A total of 1,371 individuals had self-reported depression in the 2000 MEPS sample. Of these, 833 had at least one antidepressant prescription filled during the year, 384 had at least one psychotherapy or counseling session during the year, and 938 used some form of treatment during the year. The characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 1.

Antidepressant treatment

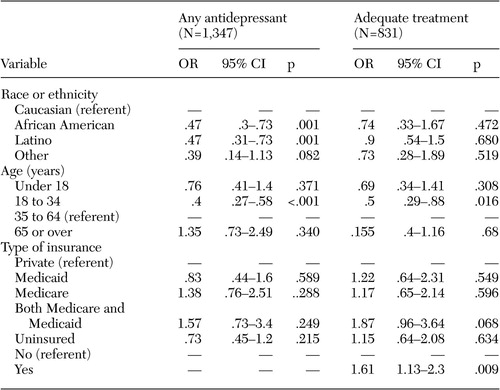

Overall, 61.9 percent of individuals with self-reported depression filled at least one antidepressant prescription during the year. African Americans (OR=.47) and Latinos (OR=.47) with self-reported depression were significantly less likely to fill an antidepressant prescription than Caucasians (Table 2). Young adults (persons aged 18 to 34 years) were significantly less likely to fill an antidepressant prescription (OR=.4) than adults aged 35 to 64 years.

Among persons with self-reported depression who filled at least one antidepressant prescription, 53 percent filled at least four antidepressant prescriptions during the year at a minimally adequate dosage. No significant differences in the probability of filling an adequate number of antidepressant prescriptions by race or ethnicity or type of insurance were observed for individuals who used antidepressants (Table 2). Adults aged 18 to 34 years were less likely than those aged 35 to 64 to fill an adequate number of antidepressant prescriptions during the year (OR=.5). Individuals who were also receiving psychotherapy or counseling were significantly more likely to have an adequate course of antidepressant treatment compared with those who were not receiving psychotherapy or counseling (OR=1.61).

Psychotherapy or mental health counseling

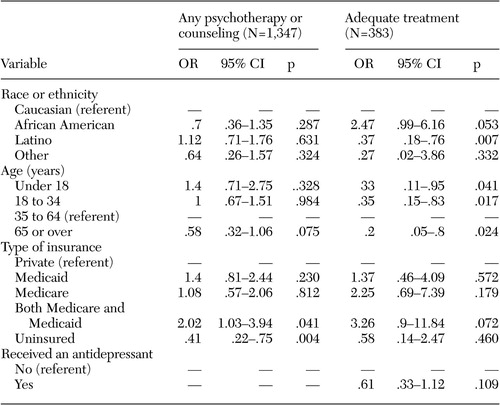

Overall, 28.2 percent of individuals with self-reported depression had at least one psychotherapy or counseling visit during the year. No significant differences in the probability of receiving psychotherapy or counseling were observed by race or ethnicity or age among individuals with self-reported depression (Table 3). However, persons without insurance were significantly less likely to receive psychotherapy or counseling (OR=.41) than those with private insurance, and individuals who were dually covered by Medicaid and Medicare were significantly more likely to receive psychotherapy or counseling than those with private insurance (OR=2.02).

An estimated 43.5 percent of individuals who received psychotherapy or counseling had at least eight psychotherapy of counseling visits during the year. Among individuals who received any psychotherapy or counseling, Latinos were significantly less likely to receive an adequate course of psychotherapy or counseling than Caucasians (OR=.37) (Table 3). Children (OR=.33) and young adults (OR=.35) were significantly less likely to receive an adequate course of psychotherapy or counseling than adults ages 35 to 64. No significant difference was noted in the probability of receiving an adequate number of psychotherapy or counseling sessions by type of insurance or by whether the individual used both psychotherapy or counseling and antidepressants.

Adequate treatment by antidepressant or by psychotherapy

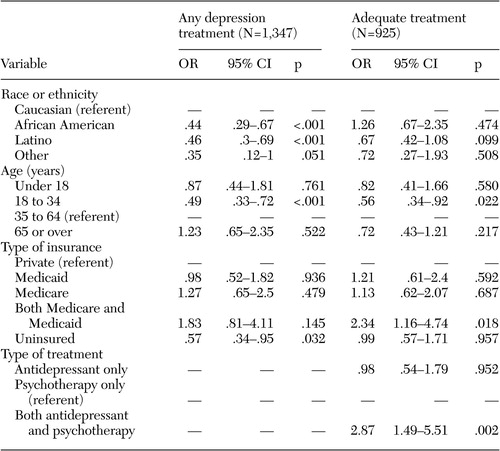

Overall, 69.4 percent of individuals with self-reported depression received at least one prescription for an antidepressant or at least one session of psychotherapy or counseling during the year. African Americans (OR=.44) and Latinos (OR=.46) were both significantly less likely to use some form of depression treatment than Caucasians (Table 4). Young adults were less likely to receive depression care (OR=.49) compared with middle-aged adults, and the uninsured were less likely to use depression care than individuals with private insurance (OR=.57).

An estimated 57 percent of persons with self-reported depression who received any depression treatment had an adequate course of treatment. Thus, overall, 39.5 percent of individuals with self-reported depression had adequate treatment based on self-reported utilization. No statistically significant differences at the p<.05 level were detected in rates of adequate care by race or ethnicity (Table 4). Young adults were significantly less likely to receive adequate treatment compared with adults aged 35 to 64 years (OR=.56). Persons who were dually covered by Medicaid and Medicare were significantly more likely to have an adequate course of treatment (OR=2.34) compared with the privately insured. Individuals who received both psychotherapy or counseling and antidepressant medications were much more likely to receive adequate treatment (OR=2.87) compared with individuals who received only psychotherapy or counseling or only antidepressants.

Discussion

These results suggest that much of the disparities in depression care may be due to differences in rates of obtaining depression treatment, as has been found in previous studies (10,16,17,19,21). It appears, for the most part, that once depression treatment is initiated, disparities in adequate care are not significant. Our study found that, among individuals who received psychotherapy or counseling, African Americans were more likely to receive an adequate course of treatment than Caucasians. Among individuals who received an antidepressant, no racial differences were observed in the probability of receiving adequate pharmacotherapy. Latinos were significantly less likely to receive any treatment and also significantly less likely to receive an adequate course of psychotherapy or counseling.

Young adults were the only age group consistently less likely to receive any treatment, less likely to fill an adequate number of prescriptions among antidepressant users, and less likely to receive an adequate number of counseling sessions. This finding may be due to the fact that young adults are less likely to use health services in general, although we did control for self-perceived health status. In contrast with previous studies, which have found that older persons use depression care less frequently than younger ones (10,15,30), this study showed no significant differences in obtaining depression care among the elderly. Some of the differences in findings between this study and others may be due to differences in samples and sample selection criteria.

Unlike some previous studies that found that persons covered by Medicaid were less likely to receive depression treatment (16,17), our study showed no differences either in obtaining depression treatment or in the adequacy of depression care once care was initiated. It may be that the quality of depression care for individuals with Medicaid has improved, as found in more recent studies (10,31).

Persons who used both psychotherapy or counseling and antidepressant medications were significantly more likely to receive adequate depression care. This finding could be due to the fact that individuals who use both treatment modalities are more likely to be seen in mental health specialty care, where rates of appropriate treatment are higher and dropout rates are lower (10,12,32). Persons who receive combination therapy may also have greater perceived need, and thus motivation, for services than those who use antidepressants only or psychotherapy or counseling only, although we did control for self-reported mental health status. Another possibility is that attending psychotherapy or counseling increases adherence to antidepressant medication regimens, increasing the probability of adequate antidepressant treatment. This last hypothesis is directly supported by our findings. However, this study provided no evidence that using antidepressants increases the probability of receiving an adequate course of psychotherapy or counseling.

Our results should be interpreted with several limitations in mind. First, identification of persons with depression was based on patient self-report. It is possible that some patients with depression were not identified as having depression and, similarly, some patients who were identified as having depression did not meet the diagnostic criteria for depression. It is also possible that reporting of depression varied by ethnic group, although a previous study showed no difference in the rate of reporting emotional problems to medical providers by ethnic group (33). However, if African Americans and Latinos underreported depression, the estimates of relative rates of receipt of any treatment would be conservative, because persons from ethnic minority groups who self-reported depression would have had higher severity levels than Caucasians. Underreporting by these groups would be less likely to affect estimates of adequate treatment for persons who received treatment because all individuals in this subsample were judged by a clinician to have depression severe enough to warrant treatment. Also, because the analysis included all individuals with an ICD-9 code of 296, some individuals with bipolar disorder were included in the analysis.

Another limitation is that the type or duration of individual psychotherapy or mental health counseling sessions was not known. In addition, the date that antidepressant medication prescriptions were filled and the number of days of medication supplied were not known. Because only treatments that were provided during the calendar year were assessed, our data might be subject to left or right censoring—that is, some individuals may have initiated a treatment regimen before the beginning of the calendar year or may have continued treatment after the end of the calendar year; for these patients, it is possible that not all prescriptions or psychotherapy or counseling were included in our data. Left censoring has also been an issue in past studies that have examined care in the previous 12 months (7,10). Also, use of depression treatment was based on self-report, which introduces the possibility of recall bias. However, because we were interested primarily in differences in adequacy of treatment among different sociodemographic groups, not the actual prevalence of adequate treatment, as long as the measurement errors were distributed randomly among respondents, these limitations should not affect the findings.

Conclusions

This study provided evidence that ethnic disparities in depression treatment result primarily from the reduced likelihood of receiving any treatment. Although we found large ethnic differences in the probability of receiving any care, there were few significant differences in the likelihood of receiving an adequate course of depression care among different sociodemographic groups. Thus initiating depression treatment may be the primary hurdle in overcoming disparities in depression care. However, even if there are few differences in the rates at which adequate depression care is provided for those who seek depression treatment, there remains much room for improvement in the overall rate of adequate depression care.

Dr. Harman is affiliated with the department of health services research, management, and policy in the College of Public Health and Health Professions of the University of Florida, P.O. Box 100195, Gainesville, Florida 32611-0195 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Edlund and Dr. Fortney are with the department of psychiatry of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock and with the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service of the Central Arkansas Veterans Health Care System in Little Rock.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of a sample of 1,371 persons with self-reported depression

|

Table 2. Odds of filling a prescription for an antidepressant among persons with self-reporteddepression and of receiving adequate care among persons who filled at least one antidepressant prescription

|

Table 3. Odds of receiving psychotherapy or mental health counseling among persons with self-reported depression and of receiving adequate care among individuals who had at least one session of psychotherapy or counseling

|

Table 4. Odds of receiving any treatment among persons with self-reported depression and of receiving adequate care among individuals who used antidepressants or psychotherapy or counseling

1. Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD: The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA 262:914–919, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Murray C, Lopez A: The Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability From Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard School of Public Health, 1996Google Scholar

3. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al: The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 289:3095–3105, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Depression Guideline Panel: Depression in Primary Care, vol 2: Treatment of Major Depression. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research, 1993Google Scholar

5. American Psychiatric Association: Practice guidelines for major depressive disorder in adults. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:S1-S26, 1993Google Scholar

6. Schulberg H, Katon W, Simon G, et al: Treating major depression in primary care practice: an update of the agency for health care policy and research practice guidelines. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:1121–1127, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Katz SJ, Kessler RC, Lin E, et al: Medication management of depression in the United States and Ontario. Journal of General Internal Medicine 13:77–85, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Wells K, Sturm R, Sherbourne C, et al: Caring for Depression. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1996Google Scholar

9. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 1999Google Scholar

10. Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, et al: The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:55–61, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Weilburg JB, O'Leary KM, Meigs JB, et al: Evaluation of the adequacy of outpatient antidepressant treatment. Psychiatric Services 54:1233–1239, 2003Link, Google Scholar

12. Fortney JC, Rost K, Zhang M: The impact of geographic accessibility on the intensity and quality of depression treatment. Medical Care 37:884–893, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Rost K, Zhang M, Fortney J, et al: Rural-urban differences in depression treatment and suicidality. Medical Care 36:1098–1107, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Brown D, Ahmed F, Gare L, et al: Major depression in a community sample of African Americans. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:373–378, 1995Link, Google Scholar

15. Lebowitz BD, Pearson J, Schneider L, et al: Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late life: consensus statement update. JAMA 278:1186–1190, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Melfi C, Croghan T, Hannah M: Access to treatment for depression in a Medicaid population. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 10:201–215, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Melfi C, Croghan T, Hanna M, et al: Racial variation in antidepressant treatment in a Medicaid population. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61:16–21, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Callahan CM: Quality improvement research on late-life depression in primary care. Medical Care 39:772–784, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Wells K, Klap R, Koike A, et al: Ethnic disparities in unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health care. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:2027–2032, 2001Link, Google Scholar

20. Sclar D, Robison L, Skaer T, et al: Ethnicity and the prescribing of antidepressant pharmacology:1992–1995. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 7:29–36, 1999Google Scholar

21. Blazer D, Hybels C, Simonsick E, et al: Marked differences in antidepressant use by race in an elderly community sample:1986–1996. Presented at the annual meeting of the Gerontological Society, San Francisco, Nov 19–23, 1999Google Scholar

22. Olfson M, Pincus H: Outpatient psychotherapy in the United States: I. volume, costs, and user characteristics. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:1281–1288, 1994Link, Google Scholar

23. Harman JS, Schulberg HC, Mulsant BH, et al: Effect of patient and visit characteristics on diagnosis of depression in primary care. Journal of Family Practice 50:1068, 2001Medline, Google Scholar

24. Katon W, von Korff M, Lin E: Adequacy and duration of antidepressant treatment in primary care. Medical Care 30:67–76, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Cohen SB: Sample design of the 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 1997Google Scholar

26. Depression Guideline Panel: Depression in primary care, vol 1: Detection and Diagnosis. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research, 1993Google Scholar

27. Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, et al: Studies of illness in the aged: the index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial functioning. JAMA 185:914–919, 1963Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Myers AM: The clinical Swiss Army knife: empirical evidence on the validity of IADL functional status measure. Medical Care 30(5 suppl):MS96-MS111, 1992Google Scholar

29. Stata Statistical Software, release 7.0, special edition. College Station, Tex, Stata Corp, 2002Google Scholar

30. Unutzer J, Katon W, Sullivan M, et al: Treating depressed older adults in primary care: narrowing the gap between efficacy and effectiveness. Milbank Quarterly 77:225–256, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Harman JS, Mulsant B, Kelleher KJ, et al: Narrowing the gap in treatment of depression. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 31:255–269, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Edlund M, Wang P, Berglund P, et al: Dropping out of mental health: patterns and predictors among epidemiological survey respondents in the United States and Ontario. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:845–851, 2002Link, Google Scholar

33. Ford DE, Kamerow DB, Thompson J: Who talks to physicians about mental health and substance abuse problems? Journal of General Internal Medicine 3:363–369, 1988Google Scholar