Length of Stay, Referral to Aftercare, and Rehospitalization Among Psychiatric Inpatients

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This retrospective study explored the interrelationship among aftercare, length of hospital stay, and rehospitalization within six months of discharge in a sample of psychiatric inpatients. METHODS: Data were analyzed for 1,481 patients who had received inpatient care at a state psychiatric hospital from November 1991 to July 1994. Logistic regression models were estimated to predict the likelihood of referral to aftercare and of readmission to a hospital within six months of the index discharge. Variables controlled for were patients' characteristics; psychiatric status at the time of discharge, including length of stay; and the availability of informal support. RESULTS: Sixteen percent of the patients received a referral to aftercare, and about 13 percent of the patients were readmitted within six months of discharge. White patients were twice as likely as African Americans to receive a referral to aftercare. Length of hospitalization and having a diagnosis of schizophrenia were also predictors of referral to aftercare. Referral to aftercare was not shown to mediate the relationship between length of stay and rehospitalization. However, having a schizoaffective disorder, a poor discharge prognosis, and a high number of previous admissions were associated with an increased risk of readmission. No other demographic characteristics were related to readmission within six months of discharge, but referral to aftercare significantly increased the risk of readmission. CONCLUSIONS: The study suggested the possibility of racial disparities in referral to aftercare and a complex relationship between referral and rehospitalization. Both these findings warrant further investigation that gives particular attention to individual-level indicators of need and system-level barriers to and facilitators of psychiatric care.

Mental health advocates, policy makers, and researchers continue to raise concerns about the negative consequences of long-term psychiatric hospitalization due to long or frequent hospital stays. The basic argument is that the longer former psychiatric inpatients can stay in the community, the more time they have to gain necessary work experience, establish and maintain an active social life, and learn other skills necessary for living independently. A critical factor in the ability to achieve and maintain a high level of functioning in the community is community support in the form of transitional care and supportive social networks. However, 40 to 60 percent of psychiatric patients who are discharged from an inpatient facility do not receive aftercare (1).

Although short hospital stays are common, approximately 40 percent of psychiatric inpatients are rehospitalized within one year of discharge (1). If some patients do in fact need hospital stays that are longer than average, the high readmission rate may be partially due to the trend toward brief hospitalizations. Some research has shown a negative relationship between length of stay and rehospitalization. Mortensen and Eaton (2) suggested that a long hospitalization reflects a greater need for placement in aftercare and an increased likelihood of receiving such care. This interpretation suggests that placement in aftercare may mediate the relationship between length of stay and rehospitalization. However, evidence of this relationship is unclear, because researchers either have not directly estimated the mediating effects, if any, of aftercare or have not provided an operational definition of aftercare (1).

In this study we used retrospective data to examine whether referral to aftercare mediated the relationship between length of stay and hospital readmission within six months of discharge. In so doing, we examined the extent to which participants' background characteristics, psychiatric status at the time of discharge—including length of stay—and level of informal support predicted referral to aftercare services and readmission to a psychiatric hospital.

Methods

Study design

The study was a chart review of participants in a two-sample diagnostic study at a 148-bed state psychiatric hospital that serves primarily indigent, involuntarily admitted patients. All components of the study were approved by the institutional review boards of the participating hospital and the investigating university. Both written and oral informed consent were obtained from eligible patients. Sample 1 consisted of all psychiatric patients admitted between November 1991 and July 1992. Sample 2 consisted of those admitted between November 1992 and July 1994. All participants had a preliminary admitting diagnosis of either a schizophrenic disorder, excluding schizophreniform disorder, or a mood disorder, excluding dysthymia (3). A total of 1,543 patients participated in the study.

During November 1995, information about the admission during which the patient was considered eligible for the study—hereafter referred to as the index admission—was extracted from the medical charts of all eligible patients. Data for three patients who died before they were discharged were excluded from the study. The study design was such that patients eligible for sample 1 should have been ineligible for sample 2. However, 59 patients were mistakenly considered eligible for both samples. To ensure that the cases were independent, one admission was randomly selected for analysis. The resulting effective sample size was 1,481, of whom 61 percent had a schizophrenic disorder and 39 percent a mood disorder.

Measures

We evaluated the effects of three variables on the likelihood of readmission within six months of discharge: participants' background characteristics, psychiatric status—consisting of diagnosis, prognosis, length of stay, and number of previous admissions—and informal support.

Background characteristics. Contradictory results have been reported on the significance of patients' background characteristics in predicting rehospitalization and aftercare (1). Consequently, four background characteristics were controlled for in all analyses: gender (men=0, women=1), race or ethnicity (white versus other), educational attainment (less than 12 years of school versus other), and age at index admission, coded as a continuous variable ranging from 21 to 60 years.

Psychiatric status. Four psychiatric status variables were controlled for in all the statistical models: primary discharge diagnosis, prognosis, length of stay of the index admission, and number of previous admissions.

Most studies have not found a consistent relationship between diagnosis and rehospitalization. Some studies have reported an association between higher rehospitalization rates and a diagnosis of schizophrenia, whereas others have reported higher rates of rehospitalization among patients who have a diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence or who have a chronic psychiatric disorder with an affective component (1). Consequently, participants' primary discharge diagnoses—hereafter referred to as the diagnosis—were categorized as schizophrenia, not including schizoaffective type; schizoaffective disorder; mood disorder; substance abuse or dependence; or other—for example, paranoid state or adjustment reaction. A binary variable was created for each diagnostic category, with 1 used to designate the presence of the disorder. The excluded diagnostic category in all analyses was schizophrenic disorder.

Attending physicians also recorded patients' prognosis at the time of discharge. A binary variable—"prognosis"—was included in all analyses, with 1 used to designate guarded, poor, or unknown and 0 used to designate good or fair.

One of the most consistent predictors of readmission is the number of previous admissions (1,4,5,6). In this study, that variable was calculated as the participant's number of admissions to the study hospital between 1972, when the hospital opened, and the index admission. Length of hospitalization was calculated as a continuous variable representing the number of days between the index admission and the discharge date.

Informal emotional support. Advocates of the community health movement note that the ability of former inpatients to become or remain independent depends on the availability of community support (1). However, researchers have not clearly identified the mechanisms by which informal support helps persons with severe and chronic mental illness. Members of a support network may provide tangible support, such as transportation, or intangible support, such as emotional support or helping the person recognize a decline in functioning that may require professional intervention such as hospitalization.

A binary variable—"emotional support"—was included in all analyses. Within the first three days of admission to the study hospital, all newly admitted patients were assessed by a nurse. Patients were asked to check categories of persons available for emotional support, such as a spouse, a son, a daughter, a friend, parents, a guardian, or other persons. The patient was coded as having a source of informal emotional support if any of the listed categories was marked or if a nonprofessional was mentioned in the "other" category. (Pastors, group home care providers, and counselors were considered to be professionals.)

Outcome variables. Researchers have used a variety of definitions of aftercare and often have not provided a clear operational definition (1). Therefore, it is not surprising that studies examining the relationship between aftercare and rehospitalization rates have had contradictory results—a positive association, a negative association, and no association (7,8,9,10,11,12,13).

For the purposes of this study, aftercare was defined as referral to a psychiatric aftercare program, such as outpatient care, foster care, or a group home, not including a nursing home. Rehospitalization was defined as being readmitted to a hospital within six months of the index discharge. Patients who were observed for less than six months after the index discharge but were not readmitted were excluded from the analysis.

Analysis

This study had two goals. The first was to determine whether referral to aftercare mediated the relationship between the length of the index hospitalization and readmission within six months. The second goal was to identify predictors of readmission within six months of discharge and receipt of referral to aftercare. To accomplish the first goal, Baron and Kenny's (14) method of testing for mediation was used. For the purposes of this study, mediation was considered to have occurred if length of stay affected the likelihood of referral to aftercare, length of stay had independent effects on the likelihood of rehospitalization within six months when aftercare was not controlled for, and aftercare affected the likelihood of readmission after length of stay was controlled for (the full model). If all three of these conditions were met and the effects of length of stay were smaller or were insignificant in the full model, it would be concluded that aftercare mediates the relationship between length of stay and readmission.

Three logistic regression models were estimated. First, referral to aftercare was regressed on length of stay. Second, the likelihood of rehospitalization within six months of discharge was regressed on length of stay. Finally, readmission within six months of discharge was regressed on length of hospital stay and referral to aftercare. Participants' background characteristics, psychiatric status, and informal support were controlled for in each of these models.

Results

Descriptive findings

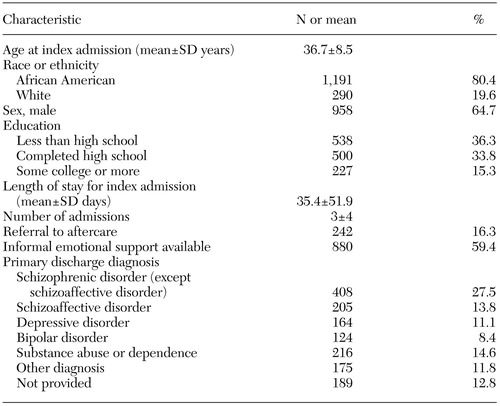

During the study period, the hospital population was 60 to 65 percent African American and 58 to 61 percent male. As can be seen from Table 1, the study sample reflected the gender profile of the hospital population, with 65 percent being male; however, African-American participants were overrepresented (80 percent of the study sample). The mean±SD age of the participants was 36.7±8.5 years. More than a third of the sample did not complete high school.

The mean duration of the index hospitalization was 35.4±51.9 days (range, one to 554 days), and the mean number of admissions to the hospital since it opened was 3±4 (range, 1 to 54). A total of 242 participants (16.3 percent) received a referral to psychiatric aftercare. A total of 188 participants (13 percent) were readmitted within six months of discharge. During the nurse's assessment, approximately 60 percent of the participants reported that they had a friend, a relative, or another nonprofessional who was available for emotional support.

A total of 461 patients (31 percent) had a discharge prognosis of fair or good. Although this study had strict diagnostic eligibility criteria, there was much more variation in the discharge diagnoses than in the admitting diagnoses. At the time of discharge, more than 40 percent of the sample had a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder; 19 percent, mood disorder; 15 percent, substance abuse or dependence; and 12 percent, another diagnosis—for example, anaphylactic shock. For 13 percent, no primary discharge diagnosis was listed.

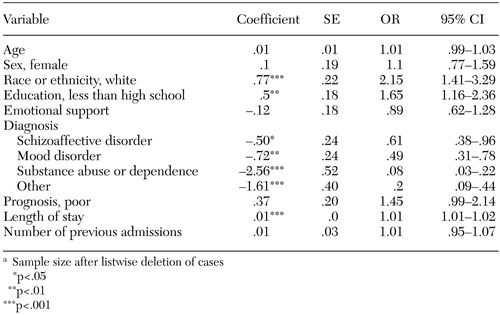

Predictors of referral to aftercare

White patients were twice as likely as African Americans to receive a referral to aftercare (Table 2). Participants who had not completed high school were about 1.5 times as likely to be referred to aftercare as those who had completed at least 12 years of school. Participants in all the diagnostic groups except schizophrenia—schizoaffective disorder, mood disorder, substance abuse or dependence, and other—were less likely to receive a referral than were participants with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The longer the index hospitalization, the more likely the participant was to receive a referral to aftercare.

Predictors of hospital readmission

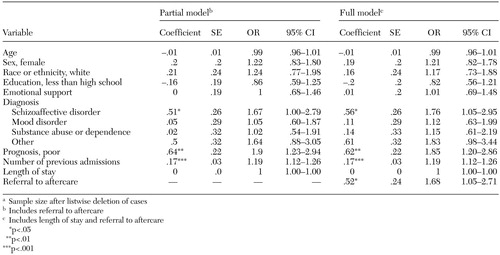

Table 3 shows the results of the logistic regression models testing whether aftercare mediates the relationship between length of stay and hospital readmission within six months of discharge. Although length of stay influenced referral to aftercare, it did not have an independent effect on readmission in the partial model, which did not control for aftercare. That is, referral to aftercare does not appear to mediate the relationship between length of stay and readmission, because no significant relationship between length of stay and readmission was found.

Table 3 also shows the results of the full model, which included all the background characteristics of the participants, emotional support, psychiatric status variables, and referral to aftercare. Neither background characteristics nor emotional support was a significant predictor of readmission within six months of discharge. Participants with a schizoaffective disorder were almost twice as likely to be readmitted as those with other schizophrenic disorders. Consistent with previous research in this area, a poor prognosis—as opposed to a fair or good prognosis—and a high number of previous admissions each increased the risk of readmission. Having a referral to aftercare significantly increased the risk of rehospitalization within six months of discharge.

Discussion and conclusions

Although length of hospital stay did not independently affect readmission, it was a significant predictor of referral to aftercare. This association between length of stay and referral to aftercare suggests that participants who had a greater need for inpatient treatment—assuming that longer hospitalization is a proxy for such need—were also those with a greater need for appropriate supportive services (2). This finding was further supported by the positive relationship found between a poor prognosis and referral to aftercare.

The typically poorer prognosis of persons with schizophrenia compared with other patients may also partially explain why the study participants who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia were more likely than those with other diagnoses to receive a referral to aftercare. Furthermore, the narrow definition of aftercare—that is, referral to psychiatric aftercare services—may also have explained why the patients with substance abuse or dependence or those in the "other" diagnostic group were less likely to receive aftercare. Specifically, the "other" group included individuals with acute physical health problems, who would be more likely to be transferred to an acute care hospital than to a psychiatric facility. Similarly, the lower probability that patients with a diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence received a referral to psychiatric aftercare services may partially reflect the mixed treatment that this patient group receives in the mental health care system.

It is unclear why there were such strong racial effects on the odds of referral to aftercare. Racial effects are often ambiguous, because race is usually strongly related to socioeconomic factors—for example, financial factors, educational background, and insurance status. The context of poverty tends to differ tremendously between racial groups, even between poor African Americans and poor white persons. For example, African Americans receive, on average, lower economic returns on their education (15), and poor African Americans are more likely than poor white persons to be geographically isolated and to live in economically homogeneous neighborhoods (16). Although the economic homogeneity of our overall sample—specifically, the sample's low income—allowed us to indirectly control for income, and although we directly controlled for education, we were unable to account for other factors related to socioeconomic status that might explain race differences in clinicians' referral behavior. For example, clinicians may be aware of racial and geographic disparities in access to affordable and effective aftercare, which may make some clinicians less likely to refer some groups of patients at all.

In addition, researchers have consistently found racial differences in help-seeking behavior and compliance with recommended treatment (17,18). Some physicians may assume, on the basis of this type of research or their own professional experience, that their African-American patients will not follow up on a referral to aftercare, so they do not even provide a referral. Another possible explanation is that African-American patients in this sample were more likely to have a comorbid substance use disorder or physical health condition that required immediate care in a nonpsychiatric setting. We strongly encourage future researchers to examine these issues more closely, paying particular attention not only to objective patient-level factors such as chronicity of symptoms and insurance status and community-level factors such as availability of services but also to clinicians' perceptions of differences between patients and how these perceptions influence referral behavior.

The lack of significance of age, race, gender, and educational attainment in predicting rehospitalization is somewhat surprising given that some studies have reported strong, although mixed, effects (1). The positive relationship between poor prognosis, number of previous hospitalizations, and rehospitalization is consistent with other studies in this area (1). Study participants with a discharge diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder were more likely than those with another type of schizophrenic disorder to be readmitted within six months—a finding that reinforces the need for future studies to distinguish between these two diagnostic groups.

The lack of effect of emotional support on aftercare as well as the positive relationship between aftercare and rehospitalization may be partially explained by measurement error, but these findings clearly need further investigation. Because the relevant assessment form did not define emotional support, the study participants may not have interpreted this variable consistently. Consequently, some participants may have been misclassified as having emotional support, thereby attenuating the true effects of that factor.

Before discussing possible ways of improving the measurement of aftercare, it is important to ask the larger question of whether the positive relationship between aftercare and rehospitalization within six months of discharge is good or bad. At the individual level, it is probably best to think of the answer as depending on the individual's circumstances. For example, the closer supervision associated with aftercare may result in an increased chance of receiving an intervention earlier and when it is most needed. On the other hand, a positive association between aftercare and rehospitalization may be considered desirable if it leads to fewer subsequent admissions or at least to a gradual increase in the length of time between subsequent admissions.

If aftercare does increase the risk of rapid readmission but leads to less rehospitalization overall, an interaction might exist between aftercare and readmissions after the index discharge. Supplementary analyses (data not shown) were conducted to test this hypothesis. However, aftercare did not have significant main effects on time to a second readmission after the index hospitalization. The lack of significant results may reflect the true relationship or may be due to insufficient sample size given that a relatively small proportion of the sample was referred to psychiatric aftercare services.

Readers should exercise caution in interpreting the relationship we found between referral to aftercare and rehospitalization. The lack of a patient tracking system across aftercare service programs did not permit us to determine whether patients who received a referral to aftercare sought or received the recommended services. Consequently, referral to aftercare services should not be equated with the receipt of those services. In addition, some research suggests that it may be important to distinguish among types of aftercare, such as outpatient psychiatric services and residential, substance abuse, and dual diagnosis programs (1,9,10,11,12,13,19). However, because of the small percentage of participants referred to aftercare programs, we were not able to analyze the data by type of referral.

In addition, as mentioned above, emotional support was undefined, which may have led to misclassification of some participants. Finally, the ability to generalize the results was further limited by the characteristics of the sample. The study hospital was an urban state psychiatric hospital that serves a predominantly indigent population. Consequently, these findings may not generalize to suburban or rural psychiatric facilities or to more affluent populations.

Despite these limitations, our findings strongly suggest a need for researchers to further explore racial differences in access to aftercare, paying particular attention to differentiating between the effects of physician bias and the effects of the needs of patients, including patients with a dual diagnosis. Because a positive relationship was found between referral to aftercare and rehospitalization within six months of discharge, additional research is clearly needed to more accurately model the effects of aftercare on rehospitalization. Researchers generally agree that aftercare can play an important role in the short-term and long-term recovery of some former psychiatric inpatients. If this finding is true, it is critical that equal access to aftercare be ensured.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by grant M-58565 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Thompson is affiliated with the department of public and community health at the University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742-2611 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Neighbors is with the department of health behavior and health education at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Dr. Munday is with the department of psychology at the University of Detroit Mercy. Dr. Trierweiler is with the program for research on black Americans in the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of a sample of 1,481 psychiatric inpatients in a study of referral to aftercare and rehospitalization

|

Table 2. Predictors of referral to aftercare in a sample of 1,077a psychiatric inpatients

a Sample size after listwise deletion of cases

|

Table 3. Predictors of rehospitalization within six months of discharge in a sample of 1,077a psychiatric inpatients

a Sample size after listwise deletion of cases

1. Klinkenberg WD, Calsyn RJ: Predictors of receipt of aftercare and recidivism among persons with severe mental illness: a review. Psychiatric Services 47:487–496, 1996Link, Google Scholar

2. Mortensen PB, Eaton WW: Predictors of readmission risk in schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine 24:223–232, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Thompson EE, Neighbors HW, Munday C, et al: Recruitment and retention of African American patients for clinical research: an exploration of response rates in an urban psychiatric hospital. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64:861–867, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Appleby L, Prakash ND, Luchins DJ, et al: Length of stay and recidivism in schizophrenia: a study of public psychiatric hospital patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:72–76, 1993Link, Google Scholar

5. Carpenter MD, Mulligan JC, Bader IA, et al: Multiple admissions to an urban psychiatric center: a comparative study. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 36:1305–1308, 1985Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Swett C: Symptom severity and number of previous psychiatric admissions as predictors of readmission. Psychiatric Services 46:482–485, 1995Link, Google Scholar

7. Laessle R, Pfister H, Wittchen H-U: Risk of rehospitalization of psychotic patients: a 6-year follow-up investigation using the survival approach. Psychopathology 20:48–60, 1987Google Scholar

8. Snowden L, Holschuh J: Ethnic differences in emergency psychiatric care and hospitalization in a program for the severely mentally ill. Community Mental Health Journal 28:281–291, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Byers ES, Cohen S, Harshbarger DD: Impact of aftercare services on recidivism of mental hospital patients. Community Mental Health Journal 14:26–34, 1978Medline, Google Scholar

10. Solomon P, Davis J, Gordon B: Discharged state hospital patients' characteristics and use of aftercare: effect on community tenure. American Journal of Community Psychiatry 141:1566–1570, 1984Link, Google Scholar

11. Moos RH: Longer episodes of community residential care reduce substance abuse patients' readmission rates. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 56:433–443, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Wan TTH, Ozan YA: Determinants of psychiatric rehospitalization: a social area analysis. Community Mental Health Journal 27:3–16, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Owen C, Rutherford V, Jones M, et al: International Update: I. Psychiatric rehospitalization following hospital discharge. Community Mental Health Journal 33:13–23, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Baron RM, Kenny DA: The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51:1173–1182, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Carnoy M, Rothstein R: Are black diplomas worth less? American Prospect 30:42–45, 1997Google Scholar

16. Massey DS: American apartheid: segregation and the making of the underclass. American Journal of Sociology 96:329–357, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Zhao S, et al: The 12-month prevalence and correlates of serious mental illness (SMI), in Mental Health, United States. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Sonnenschein MA. Pub no SMA 96–3098. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 1996Google Scholar

18. Sussman LK, Robins LN, Earls F: Treatment-seeking for depression by black and white Americans. Social Science and Medicine 24:187–196, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Mares A, McGuire J: Reducing psychiatric hospitalization among mentally ill veterans living in board-and-care homes. Psychiatric Services 51:914–921, 2000Link, Google Scholar