Criminal Victimization of Persons With Severe Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The types and amounts of crime experienced by persons with severe mental illness were examined to better understand criminal victimization in this population. METHODS: Subjects were 331 involuntarily admitted psychiatric inpatients who were ordered by the court to outpatient commitment after discharge. Extensive interviews provided information on subjects' experience with crime in the previous four months and their perceived vulnerability to victimization, as well as on their living conditions and substance use. Medical records provided clinical data. RESULTS: The rate of nonviolent criminal victimization (22.4 percent) was similar to that in the general population (21.1 percent). The rate of violent criminal victimization was two and a half times greater than in the general population—8.2 percent versus 3.1 percent. Being an urban resident, using alcohol or drugs, having a secondary diagnosis of a personality disorder, and experiencing transient living conditions before hospitalization were significantly associated with being the victim of a crime. In the multivariate analysis, substance use and transient living conditions were strong predictors of criminal victimization; no demographic or clinical variable was a significant predictor. Given the relatively high crime rates, subjects' perceived vulnerability to victimization was unexpectedly low; only 16.3 percent expressed concerns about personal safety. Those with a higher level of education expressed greater feelings of vulnerability. CONCLUSIONS: The study found a substantial rate of violent criminal victimization among persons with severe and persistent mental illness. Results suggest that substance use and homelessness make criminal victimization more likely.

Criminal victimization has been on the rise in the United States in recent decades as the amount and types of violence have increased (1,2). Victimization not only causes physical injury and death, but also takes its toll in psychological problems. Community surveys as well as studies of victims suggest that people who are assaulted have an increased risk of psychiatric symptoms and long-term psychiatric disorders (3,4,5). Studies of clinical populations indicate high rates of lifetime victimization among psychiatric patients (6,7). It is estimated that from 10 to 20 percent of expenditures on mental health services are for treatment of victims of childhood abuse 1.

Routine psychiatric examination often fails to uncover abuse. However, standardized interviews that inquire directly about exposure to traumatic events tend to find high rates of victimization within families. Childhood abuse rates as high as 81 percent have been reported in studies that probed for multiple types of abuse, such as physical and sexual abuse and neglect, and studies that used broader definitions of abuse, such as emotional and verbal abuse (6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15).

Not only may abuse be a risk factor for psychiatric disorders, but mental illness may be a risk factor in victimization (16,17). Once mental illness develops, a symptomatic individual may be subject to more abuse (18,19). In addition to a history of childhood abuse, current victimization is common among adult psychiatric patients (16,17,20,21). One study that probed for recent violence in a sample of 69 newly hospitalized patients found that 62.8 percent of patients, both male and female, reported physical victimization by their partners, and 45.8 percent described abuse by other family members 22.

Most studies of victimization of persons with mental illness have focused on domestic violence. Their victimization outside the home has not been studied as much, yet many persons with severe mental illness are poor and live in impoverished, dangerous neighborhoods with high crime rates. On the streets of these neighborhoods, people with severe mental illness are particularly likely to be victimized because of both their mental illness and the social conditions in which they live. Their visible vulnerabilities, isolation, lack of work, lack of protected environments, and problems with alcohol and drugs can make them easy targets for criminal violence.

Only one empirical study has focused on the criminal victimization of mental patients 23. That study was done in the early 1980s before the large increases in homelessness, drug abuse, and comorbidity among persons with severe mental illness (24,25). The societal changes behind these increases have raised the risk of criminal victimization among psychiatric patients in the community. The earlier study was confined to residents of board-and-care homes, omitting two major groups of mentally ill persons—homeless persons and persons living in their own or their families' homes. Homeless persons would be expected to have higher criminal victimization rates, while those living in their own homes or their families' homes would be expected to have lower rates than those in board-and-care homes (26,27,28). One recent study found rates of physical assault and rape to be so high among episodically homeless women with serious mental illness that the researchers termed such victimization "normative" experiences for the group 29.

This study reported here focused on criminal victimization of severely mentally ill persons living in the community in a variety of residential settings in the early to mid-1990s. It examined the amount and type of criminal victimization among a large sample of recently involuntarily hospitalized patients. Characteristics of persons who were victims of crime and those who were not were identified, and predictors of criminal victimization were examined within a multivariate logistic regression analysis. Our focus on criminal victimization essentially narrows the definition of victimization, excluding other types of victimization such as emotional, mental, and verbal abuse 30 and economic and social exploitation (31,32).

Methods

Design and sample

The analysis used baseline data on 331 subjects in a larger study of the effectiveness of outpatient commitment 33. Subjects were involuntarily admitted persons with severe mental illness who were recruited from the admissions unit of a state mental hospital and the psychiatric units of three general hospitals between November 1992 and March 1996 and who were court-ordered to outpatient commitment after hospital discharge.

To be recruited, subjects had to be at least 18 years old, diagnosed as having a severe mental disorder (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, an affective disorder with psychotic features, or another psychotic disorder), and to be functionally impaired according to state criteria for severe and persistent mental illness. Subjects had to have been ill for at least one year and had to have had one or more hospitalizations totaling at least 21 days within the past two years. Subjects also had to be approved by the hospital treatment team as appropriate candidates for outpatient commitment, to be ordered to outpatient commitment by the court, and to be residents of counties participating in the study.

We identified eligible patients from daily hospital admission records and discussion with treatment team members. While these patients were still hospitalized awaiting their period of outpatient commitment, we met with them to describe the study, explain the interviews required and the confidentiality of information, and obtain their consent for participation. Subjects were offered improved access to services via case management, a service not generally available; monetary remuneration ($10) for each follow-up interview after hospital discharge, and possible random assignment to release from their outpatient commitment orders unless they had a documented history of serious violence. Of 374 identified eligible patients, only 43 (11.5 percent) refused to participate, a low refusal rate (12,34,35).

The mean±SD age of the 331 patients in the final sample was 41.3± 10.7 years, with a range from 20 through 70 years. A total of 178 patients (53.8 percent) were male. A total of 219 patients (66.2 percent) were African American, 110 were white (33.2 percent), one was Hispanic, and one was Asian. About a fifth of the patients (N=67) were married or cohabiting. A total of 207 patients (62.5 percent) lived in the urban and suburban areas of four cities, and the rest (N= 124) lived in small towns or rural sections of the nine participating counties. Nearly three-fourths (N=239) had graduated from high school.

The mean±SD number of psychiatric hospital admissions in the previous year was 1.5±1. The mean±SD Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score at discharge was 48.8± 7.9. Because the initial interviews occurred during hospitalization, most respondents' functioning had improved since admission; however, consistent with persistent disabling symptoms, patients still showed serious impairment in social, occupational, or school functioning (36,37,38). Just over half (185 patients, or 55.9 percent) had a primary discharge diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, 103 (31.1 percent) had an affective disorder with psychotic features, and 43 (13 percent) had another psychotic disorder. Reliability checks of the discharge diagnosis with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) 38 for the first third of the sample produced such a high level of agreement that SCID assessments were discontinued.

Approximately one-eighth of the sample (41 patients, or 12.4 percent) had a second diagnosis of a personality disorder, and 70 patients (21.1 percent) had an alcohol or drug disorder. However, both personality and substance use disorders tend to be underdiagnosed. Based on self-report, collateral report, and hospital records, 94 patients (28.4 percent) had used illicit drugs at least once a month during the four months before the index hospitalization, and 160 patients (48.3 percent) had used alcohol at least once a month during that period.

Research has suggested that the true prevalence of problematic substance use approaches 50 percent among persons with serious and persistent mental illness, although such problems often go undetected, and that any amount of alcohol or illicit drug use can lead to problems and tends to complicate treatment in this population (39,40). Following this line of argument, we used a broader measure of comorbidity than a diagnosis of a substance use disorder. We measured occasional alcohol or drug use in the previous four months. Just over half of our sample (178 patients, or 53.8 percent) were identified as having some co-occurring substance use by this definition.

Subjects generally had very low incomes, with a median and mode of $500 a month from all sources. Almost two-thirds had no earned income (N= 212). Approximately a third (N=111) received Supplemental Security Income; 127 patients (38.4 percent) received Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI); 28 patients (8.5 percent) received Aid to Families With Dependent Children; and 101 patients (30.5 percent) received food stamps. Few received either unemployment compensation (eight patients, or 2.4 percent) or subsidized housing (36 patients, or 10.9 percent). Most lived in their own or in their parents' homes (261 patients, or 78.9 percent). However, 54 (16.8 percent) experienced transient living conditions or were homeless at least part of the time; that is, they slept in an empty building, public shelter, or church or slept outside without shelter.

Measurement and data analyses

Patients in the study were given an extensive interview in the hospital, which included measures of health and mental health functioning and indicators of victimization. We measured both actual criminal victimization and their perceived vulnerability to victimization by responses to direct questions about their experiences in the previous four months. Actual victimization was defined by subjects' being victims once or more than once of violent crime, such as assault, rape, or mugging, or of nonviolent crime, such as burglary, theft of property or money, or being cheated.

Perceived vulnerability to victimization was defined by subjects' responses on a 7-point scale to questions about how safe they felt in the neighborhood where they lived before entering the hospital and how they felt about their personal safety. Lower scores on the scale indicate greater feelings of vulnerability. Both actual victimization and the victimization vulnerability items are from the Quality of Life Interview 41.

We first determined the amount of violent and nonviolent victimization and then used chi square tests to examine which patient characteristics were associated with each type of victimization. To examine predictors of victimization, we dichotomized the dependent variable—victim of any crime and not a crime victim—and modeled it using logistic regression.

We expected to find high rates of criminal victimization in our sample, especially from violent crime, because of the large proportions of persons with characteristics statistically associated with violent crime and criminal victimization: being of low income, male, and African American and abusing alcohol or illicit drugs (42,43,44). We also expected that severe mental illness itself would be an additional factor leading to criminal victimization. Given the tendency in the general population to overestimate the risk of being criminally victimized 44, the tendency of persons with low levels of education and income to report greater fear of criminal victimization 42, and the expected high level of violent criminal victimization in our sample, we also expected a high level of perceived vulnerability to victimization.

Results

Amount of victimization

The results were as expected for violent criminal victimization. The 331 patients reported high levels or victimization. Twenty-seven patients (8.2 percent) were victims of a violent crime in the previous four months, a rate of violent victimization well above the 3.1 percent annual rate of violent criminal victimization in the U.S. general population (42,43). On the other hand, the rate was comparable to the 8 percent annual rate found a decade earlier among mentally ill patients who lived in board-and-care homes in Los Angeles 23.

As with the general population, a much higher proportion of our sample—74 patients, or 22.4 percent—reported that they were victims of nonviolent crime in the previous four months. Their nonviolent victimization rate is similar to the 21.1 percent annual rate in the general population (42,43). Some of the nonviolent crime victims were also victims of violent crime (11 patients, or 3.4 percent), yielding a total of 90 patients who had been victimized and a victimization rate of 27.2 percent.

Unexpectedly, the level of perceived vulnerability to victimization was lower than actual victimization. In answering questions about perceptions of neighborhood and personal safety, 194 subjects (58.9 percent) expressed satisfaction and even comfort with their physical security, while 54 subjects (16.3 percent) expressed perceptions of vulnerability to victimization. Our questions are not identical to those asked in a national survey 42; however, that survey also found that a large proportion of the general population felt relatively safe, with a minority expressing a risk of victimization.

Characteristics of victims

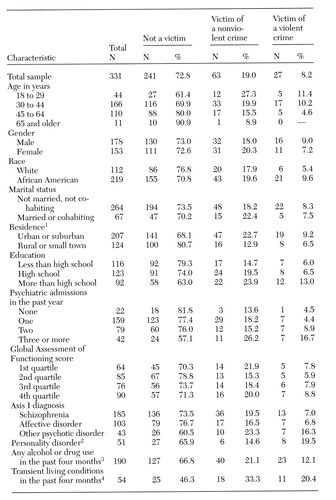

Table 1 presents the characteristics of patients reporting victimization; for each patient, only the most serious victimization was counted. As in the general population 45, younger persons, African Americans, and urban residents had a tendency to report more victimization in general and more violent victimization in particular. High school graduates also reported more victimization. However, among these sociodemographic variables, only place of residence was significantly related to criminal victimization. Persons with severe mental illness living in urban and suburban areas were significantly more likely to be victims of nonviolent and violent crimes than their counterparts living in small towns and rural areas.

The clinical variables of number of admissions to a psychiatric hospital in the previous year, primary diagnosis, and global functioning as measured by the GAF were not associated with being victimized. The only diagnostic variable significantly associated with victimization was a secondary diagnosis of a personality disorder.

As Table 1 shows, of the four variables with significant bivariate associations with criminal victimization, occasional alcohol or drug use in the previous four months had the highest level of statistical significance.

Housing type was also significantly associated with being victimized. Similar to findings of previous studies (28,29), our results indicated that patients who had any transient sleeping or homelessness in the previous four months were much more likely to be victimized than those with stable housing. Compared with those who had stable housing, these patients were twice as likely to be victims of nonviolent crime and three and a half times as likely to be victims of violent crime.

Because of the small number of patients in the sample who were victims of violence (N=27), we combined violent and nonviolent victimization to create a dichotomous variable, victim of any crime. We used this measure of violence, instead of the trichotomous variable used in the analyses shown in Table 1, to examine bivariate relationships between victimization and patient characteristics. We obtained essentially the same results, except that age and education were significantly related to victimization (p<.05).

Criminal victimization and perceived vulnerability to victimization were found to be associated. Subjects who were victims of violent or nonviolent crimes were significantly more likely to report that they did not feel personally safe or that they did not feel safe in their neighborhoods. Scores were significantly correlated with the dichotomous variable measuring actual victimization (r= -.172, p<.01). The vulnerability score had a significant correlation with only one patient characteristic, a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (r=-.120, p<.05). Sample members who had either of these diagnoses were more likely to say they did not feel safe.

Multivariate analysis

Using logistic regression to discern the relative influence of patient characteristics on actual victimization, we entered the basic demographic covariates of age, gender, and race first and included them in all models of being a victim of any crime (the dichotomous variable). Subsequent models sequentially evaluated the other three demographic variables (education, marital status, and rural or urban residence), the clinical variables (diagnosis and number of admissions in the previous year), substance use, and housing. Stepwise selection procedures were used to qualify variables for inclusion in those models.

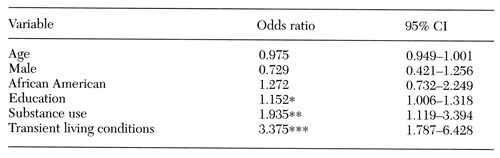

Table 2 presents the final model. Age, gender, and race were not significantly associated with criminal victimization, although these variables were forced into the model first. In addition, no clinical variable was significantly associated with victimization. Education was the single demographic variable with a significant association—having more education increased the odds of being victimized, but only slightly (1.152 times). Two variables made strong and significant contributions in the final model: occasional substance use in the previous four months increased the odds of criminal victimization almost twofold, and transient living conditions during that time increased the odds almost three and a half times.

When we duplicated this analysis using the trichotomous variable (nonvictim, victim of a nonviolent crime, and victim of a violent crime), the results were essentially the same as those of the previous model. Neither the basic demographic variables nor the clinical variables made a significant contribution, whereas the odds of violent or nonviolent victimization doubled with any alcohol or drug use and more than tripled with homelessness.

Discussion and conclusions

In the four months before being involuntarily hospitalized, the 331 persons with severe mental illness in our sample experienced a level of nonviolent criminal victimization comparable to that in the general population. However, the rate of violent criminal victimization in the sample was high, more than two and a half times the rate in the general population. Even though such a large proportion of sample members were victims of violent crime, they perceived relatively little threat of victimization, possibly because of the high proportion with stable housing who were living in their own or their parents' homes. Another reason may have been that they had lower expectations of safety than persons in the general population.

Bivariate analysis indicated that urban subjects, those who reported any use of alcohol or drugs, those with a secondary diagnosis of a personality disorder, and those who had been homeless in the previous four months were more likely to be victims of violent crime and of any crime. The multivariate analysis indicated that substance use and homelessness were so strongly related to being the victim of a violent or nonviolent crime that all the other variables except education lost statistical significance.

Having more education increased victimization, contrary to the expected inverse association 45. This association might be attributable to our sample's being at the low end of the socioeconomic scale combined with a greater sensitivity to violations of their person among individuals with higher levels of education. Previous research has found a similar relationship between level of education and perceptions of coercion 46.

The high rate of violent victimization in our sample cannot be explained by the rate in the state. Although no comparable data exist on violent victimization in North Carolina, the state is below the national average for violent crime—679.3 versus 746.8 per 100,000 population 47. The high rate is also not likely due to the sampled counties' having a higher rate than other areas of the state, because a study of four violent crimes showed that rates of robbery, rape, and aggravated assault were no higher in the sampled area, although part of the area had a higher rate of simple assault 48.

Because our data are cross-sectional, inferences about causation should be made with caution. Although the independent variables examined in this study probably measured characteristics that existed before any reported recent victimization, the clinical variables, as well as substance use and homelessness, may have either preceded or followed criminal victimization in a longer time frame. Our data also are subject to error in subjects' recall; some instances of victimization may not have been reported, and some experiences may have been distorted.

A third source of error is the lack of probing for victimization in the interviews, which probably caused underreporting of some victimization. Underreporting is especially the case with domestic violence because victims tend not to consider assaults by family and acquaintances in the home as crimes, or even as abuse, although they are legally defined as criminal acts (22,29). Nonetheless, self-reports of victimization are better than police records, which are known to underestimate the amount of crime and victimization.

Unfortunately, our data provide little information about the specific type of crime or the context in which it occurred. We do know that criminal victimization was associated with living in an urban area, having a personality disorder, using substances, and being homeless. These associations suggest that the likelihood of criminal victimization for persons with severe mental illness increases in certain contexts and with certain behaviors. A number of studies have suggested the same, reporting that those who are victimized are distinguished by a constellation of homelessness, alcohol problems, drug dependence, and mental problems (27,28,49). The association we found between victimization and a higher level of education is more of an anomaly. We suggest that rather than making persons with serious mental illness more vulnerable or putting them at greater risk, education affects their perception so they are more likely to define incidents as criminal.

Several criminology studies have found victimization among persons without mental disorders to be positively associated with criminal behavior, which again suggests an ecological dynamic (50,51,52,53,54)—that is, individuals are victimized because they endanger themselves by engaging in criminal activity. Drug use among our sample of poor persons with severe and persistent mental illness might bring them into criminal activity and into dangerous situations and places 29. Lehman and Linn's earlier study 23 of criminal victimization of persons with mental illness found that mentally ill victims of violent crime engaged in criminal activities more than mentally ill persons who were not victims.

Consistent with their data, additional chi square analysis of our data showed a significant positive association between being picked up or arrested for any crime and criminal victimization: those who were picked up or arrested for any offense were one-third more likely to have been a victim of a nonviolent crime and three times more likely to have been a victim of a violent crime (χ2=13.21, df= 2, p=.001). The association is even stronger in the case of substance abuse infractions: those who were picked up or arrested for an alcohol or drug offense were almost twice as likely to have been the victim of a nonviolent crime and more than five times as likely to have been the victim of a violent crime (χ2=23.60, df=2, p=.001). The question is still open, however, because both sets of data are only cross-sectional, and thus they are unable to address timing sequence and causality.

Future research should investigate the specific types of crime committed against persons with severe mental illness and the contexts in which such crimes occur. Knowledge of type and context would help in devising programs to reduce victimization among persons with severe mental illness and help us understand the relationship between criminal behavior and criminal victimization in this population. Our study emphasizes the importance of efforts to provide stable and safe housing for persons with severe and persistent mental illness so that they can feel secure enough to have a sense of control and a chance to benefit from treatment. Our study also points to the need for effective substance abuse treatment for persons with severe mental illness.

Acknowledgment

Support for this research was provided by grant MH-48103 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Marvin Swartz, M.D., principal investigator.

Dr. Hiday is professor of sociology in the department of sociology and anthropology at North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina 27695 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Swartz is associate professor and vice-chairman for clinical services, Dr. Swanson is assistant professor, Dr. Borum is assistant clinical professor, and Dr. Wagner is assistant research professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, North Carolina.

|

Table 1. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of 331 inpatients with severe mental illness interviewed about whether they had been the victim of a crime

1χ2=6.29, df=2, p=.043, for the difference in crime rates between urban and rural residents

2χ2=8.18, df=2, p=.017, for the difference in crime rates between those with and without a personality disorder

3χ2=11.66, df=2, p=.003, for the difference in crime rates between those with any substance use and those with no use

4χ2=24.96, df=2, p=.001, for the difference in crime rates between those with transient and stable housing

|

Table 2. Variables predicting being a victim of a nonviolent or violent crime among 331 inpatients with severe mental illness

*p<.05

**p<.01

***p<.001

1. Miller TR, Cohen MA, Wiersema B: Victim Costs and Consequences: A New Look. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, 1996Google Scholar

2. Staub E: Cultural-societal roots of violence: the examples of genocidal violence and of contemporary youth violence in the United States. American Psychologist 51:117-132, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Frank F, Anderson PA: Psychiatric disorders in rape victims: past history and current symptomatology. Comprehensive Psychiatry 28:77-82, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Mullen PE, Romans-Clarkson SE, Walton VA, et al: Impact of sexual and physical abuse on women's mental health. Lancet 1:841-845, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Winfield I, George LK, Swartz M, et al: Sexual assault and psychiatric disorders among a community sample of women. American Journal of Psychiatry 147:335- 341, 1990Link, Google Scholar

6. Lipschitz DS, Kaplan ML, Sorkern J, et al: Prevalence and characteristics of physical and sexual abuse among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatric Services 47:189-191, 1996Link, Google Scholar

7. Bryer JB, Nelson BA, Miller JB, et al: Childhood sexual and physical abuse as factors in adult psychiatric illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 144:1426-1430, 1987Link, Google Scholar

8. Craine IS, Henson CE, Colliver JA, et al: Prevalence of a history of sexual abuse among female psychiatric patients in a state hospital system. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:300-304, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

9. Jacobson A: Physical and sexual assault histories among psychiatric outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry 146:755- 758, 1989Link, Google Scholar

10. Jacobson A, Herald C: The relevance of childhood sexual abuse to adult psychiatric inpatient care. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:154-158, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

11. Jacobson A, Richardson B: Assault experiences of 100 psychiatric inpatients: evidence of the need for routine inquiry. American Journal of Psychiatry 144:908- 913, 1987Link, Google Scholar

12. Muenzenmaier K, Meyer I, Struening E, et al: Childhood abuse and neglect among women outpatients with chronic mental illness. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:666-670, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

13. Rosenfeld A: Incidence of a history of incest among 18 female psychiatric patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 136:791- 795, 1979Link, Google Scholar

14. Rose SM, Peabody CG, Stratigeas B: Undetected abuse among intensive case management clients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:499-503, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

15. Stein M, Walker J, Anderson G, et al: Childhood physical and sexual abuse in patients with anxiety disorders in a community sample. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:275-277, 1996Link, Google Scholar

16. Estroff SE, Zimmer C: Social networks, social support, and violence among persons with severe, persistent mental illness, in Violence and Mental Disorder. Edited by Monahan J, Steadman HJ. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1994Google Scholar

17. Estroff SE, Zimmer C, Lachicotte WS, et al: The influence of social networks and social support on violence by persons with serious mental illness. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:669-679, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

18. Eron LD, Gentry JH, Schlegel P: Reason to Hope: A Psychosocial Perspective on Violence and Youth. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1994Google Scholar

19. Hiday VA: The social context of mental illness and violence. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36:122-137, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Carmen E, Rieker P, Mills T: Victims of violence and psychiatric illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 141:378-383, 1984Link, Google Scholar

21. Miller LJ, Finnerty M: Sexuality, pregnancy, and childrearing among women with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Psychiatric Services 47:502-506, 1996Link, Google Scholar

22. Cascardi M, Mueser KT, DeGiralomo J, et al: Physical aggression against psychiatric inpatients by family members and partners. Psychiatric Services 47:531-533, 1996Link, Google Scholar

23. Lehman AF, Linn LS: Crimes against discharged mental patients in board-and-care homes. American Journal of Psychiatry 141:271-274, 1984Link, Google Scholar

24. Link BG, Susser E, Stueve E, et al: Lifetime and five-year prevalence of homelessness in the United States. American Journal of Public Health 84:1907-1912, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Rossi P: Down and Out in America: The Origins of Homelessness. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1989Google Scholar

26. D'Ercole A, Struening E: Victimization among homeless women: implications for service delivery. Journal of Community Psychology 18:141-152, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

27. North CS, Smith EM, Spitznagel E: Violence and the homeless: an epidemiological study of victimization and aggression. Journal of Traumatic Stress 7:95-110, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Padgett DK, Struening E: Victimization and traumatic injuries among the homeless: associations with alcohol, drug, and mental problems. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 62:525-534, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Goodman LA, Dutton MA, Harris M: Episodically homeless women with serious mental illness: prevalence of physical and sexual abuse. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 65:468-473, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Loring MT: Emotional Abuse. Lexington, Mass, Lexington Books, 1994Google Scholar

31. Mirowsky J: Disorder and its context: paranoid beliefs as thematic elements of thought problems, hallucinations, and delusions under threatening social conditions. Research in Community and Mental Health 5:139-184, 1985Google Scholar

32. Mirowsky J, Ross CE: Paranoia and the structure of powerlessness. American Sociological Review 48:228-239, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Swartz MS, Burns BJ, Hiday VA, et al: New directions in research on involuntary outpatient commitment. Psychiatric Services 46:381-385, 1995Link, Google Scholar

34. Lidz CW, Mulvey EP, Gardner WP: The accuracy of prediction of violence to others. JAMA 269:1007-1011, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Scheid-Cook TL, Wooten K, Hiday VA: Mental patients eager and willing to help sociological research. Sociology and Social Research 72:57-61, 1987Medline, Google Scholar

36. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

37. Patterson DA, Lee MS: Field trial of the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale, Modified. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:1386-1388, 1995Link, Google Scholar

38. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbons M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

39. Drake RE, Alterman A, Rosenberg SR: Detection of substance use disorders in severely mentally ill patients. Community Mental Health Journal 29:175-192, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Drake RE, Osher FC, Noordsy DL, et al: Diagnosis of alcohol use disorders in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 16:57-67, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Lehman AF, Burns BJ: Severe mental illness in the community, in Quality of Life Assessment in Clinical Trials. Edited by Spiker B. New York, Raven, 1990Google Scholar

42. Bureau of Justice Statistics: Criminal Victimization in the United States, 1992. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, 1994Google Scholar

43. Klause PA: The Costs of Crime to Victims. Washington DC, US Department of Justice, 1994Google Scholar

44. Conklin J: Criminology, 5th ed. Boston, Allyn & Bacon, 1995Google Scholar

45. Reiss AJ, Roth JA: Understanding and Controlling Violence. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1993Google Scholar

46. Hiday VA, Swartz MS, Swanson J, et al: Patient perceptions of coercion in mental hospital admission. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 20:227-241, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Crime in the United States 1994: Uniform Crime Report. Washington, DC, Federal Bureau of Investigation, 1995Google Scholar

48. The North Carolina Violent Crime Assessment Project. Raleigh, North Carolina Governor's Crime Commission, 1992Google Scholar

49. Weitzman BC, Keckman JR, Shinn M: Predictors of shelter use among low income families: psychiatric history, substance abuse, and victimization. American Journal of Public Health 82:1547-1550, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Fagen JA, Piper ES, Cheng Y: Contributions of victimization to delinquency. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 78:586-613, 1987Crossref, Google Scholar

51. Lauritsen JL, Laub JH, Sampson RJ: Conventional and delinquent activities: implications for the prevention of violent victimization among adolescents. Violence and Victims 7:91-108, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Sampson RJ, Lauritsen JL: Violent Victimization and Offending: Individual, Situational, and Community-Level Risk Factors. Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 1992Google Scholar

53. Sampson RJ, Lauritsen JL: Individual and community factors in violent offending and victimization, in Understanding and Controlling Violence, vol 3. Edited by Reiss AJ, Ross JA. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1993Google Scholar

54. Tardiff K, Marzuk PM, Leon AC: Homicide in New York City: cocaine use and firearms. JAMA 272:42-46, 1994Google Scholar